The 20 Most Livable Towns and Cities in America

The past year showed us all that having access to the outdoors is essential for our health and well-being. It also magnified the inequities inherent in that access. For 2021’s Best Towns package, we chose 13 of the country’s most diverse places and evaluated them according to the factors that matter today: sustainability, affordability, and outdoor equity. Here are the cities of tomorrow.

Heading out the door? Read this article on the Outside app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

In the two decades since we began running our annual list of the best places to live, our goal has always been to surprise you. We’ve found little-known towns that were on the verge (yes, there was a time when Bend, Oregon, held that distinction) and helped you see enduring outdoor hot spots in a novel light. We’ve focused on new adventure draws and emerging craft-beer scenes. We’ve made our selections by committee, by submission, and by executive decision fiat. This time, we’re taking a different approach.

As Americans struggled with challenges brought on by COVID-19, nature became an antidote. “During the pandemic, the wealthy fled urban areas for country homes, while suburbanites spread out in backyards and visited nearby parks,” says Ronda Chapman, equity director at the Trust for Public Land (TPL). “In too many cities, however, residents without shaded, tree-lined streets and close-to-home public green spaces found it much more challenging to get outside.” This made us ask: How do our most diverse cities fare when it comes to important factors like green infrastructure and outdoor access?

We looked through a few different lenses. First we examined 2020 demographic data from personal-finance website WalletHub, representing the socioeconomic and cultural diversity of cities across the U.S. Of course, how diverse a place is doesn’t predict how inclusive it is. So we dug deeper, with on-the-ground reporting about how these cities are getting more people of color outside—and how they’re falling short.

Next up: the sustainability lens. There’s no separating outdoor from green equity. Creating safe and reachable parks is as much an access issue as it is an ecological one. Advancing clean-energy legislation that doesn’t just benefit white communities promotes environmental justice and supports our climate future. We looked at how the most multicultural cities compare with a recent report from WalletHub that rated the 100 most populated places according to their green policy and investment. Those that scored the highest made it to our second tier. Then we factored in affordability—and the pandemic-fueled changes to the housing market—by only selecting cities with a median home price of less than $600,000.

“We’ve often said that the pandemic has been an amplifier of inequities that were already there,” says José González, founder of the outreach and advocacy organization Latino Outdoors. “If we take old redlining maps and overlay them with COVID-19 numbers, with lack of park access, with other failing health components, you see a very strong correlation.”

Solving structural inequities is a matter of redesigning these maps, says González. While we’re seeing signs of this in recent legislation and renewed efforts from local stewards and nonprofits, there’s still a lot of work to be done. There also needs to be increased emphasis on making these outdoor spaces more culturally inclusive. “There might be a great trail system that’s reachable from the city, but if I go and get this feeling of this is not for you, then that is a barrier. Each of us has a responsibility to change the narrative surrounding who is welcome in the outdoors,” González says. —Erin Riley

Our Rating Metrics

Diversity: A 2021 report from personal-finance site WalletHub ranked the 501 most populated cities based on the diversity of their socioeconomic, cultural, household, and religious makeup. The rankings drew on 13 specific metrics, including educational attainment and languages spoken. On the scorecards we include for each city, we provide that city’s WalletHub ranking.

Sustainability: A 2019 WalletHub report ranked the 100 most populated cities according to investment in green initiatives. It used 28 metrics, including air quality and the ability to get to work using public transportation. Again, on our scorecard, we give the WalletHub ranking.

Affordability: Median home prices are based on projections through May 2021 provided by the real estate website Zillow.

Outdoor Equity: In addition to our own reporting, we used data from a 2021 Trust for Public Land report on the percentage of each city that consists of parkland, along with the percentage of residents of color who live within a ten-minute walk of a park.

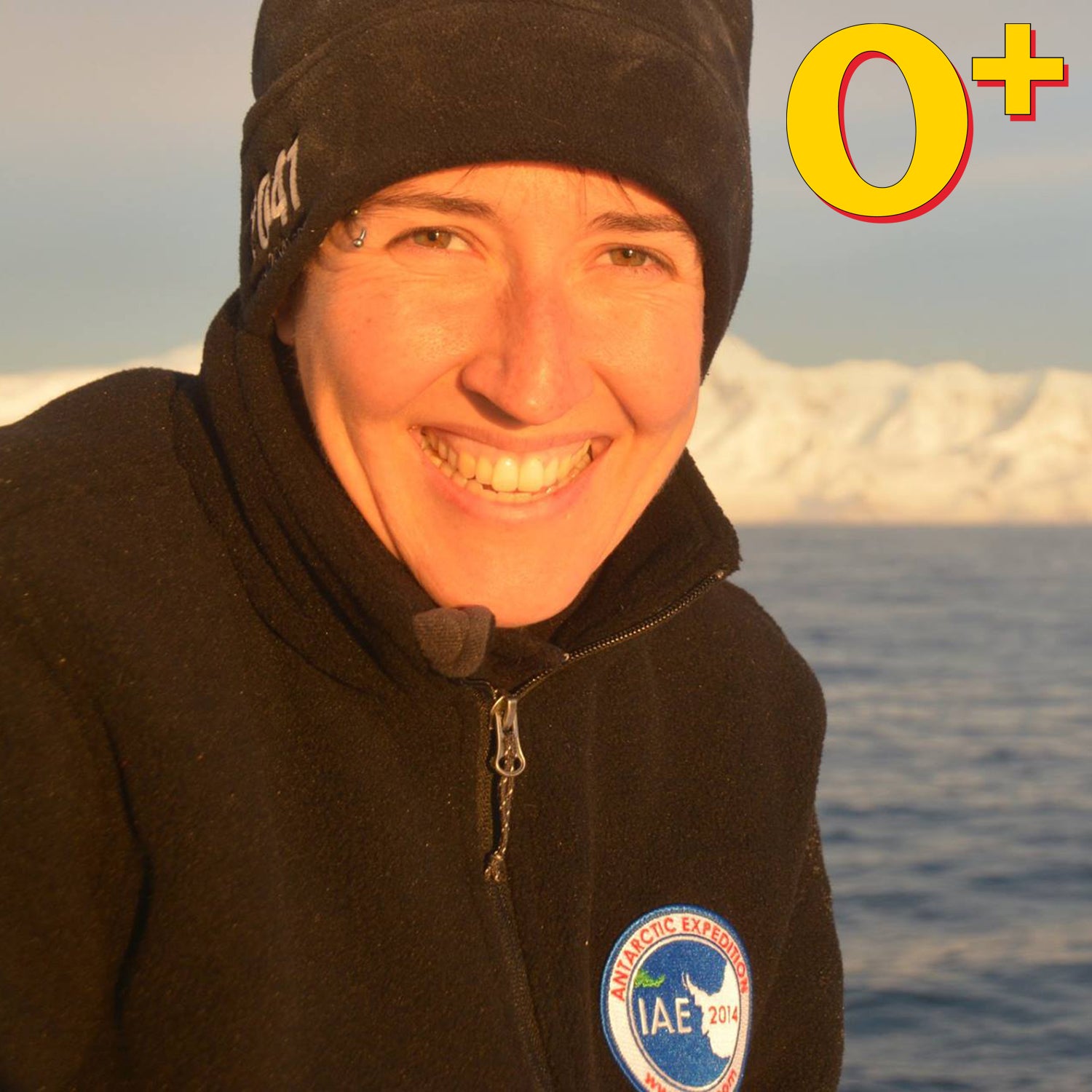

Meet Our Newest Outside+ Members

To get a better sense of what outdoor access looks like in these cities, we tapped a local expert in each to provide some intel. From new parks to greater state-level investment, our experts shared highlights of their favorite places and what improvements they’re seeing—or not. As community leaders who are actively helping more underrepresented groups get into nature, we’re excited to welcome them to Outside+, a growing community of adventurers who believe in the unifying potential of the outdoors.