Every year 16 December is celebrated in Bangladesh as a ‘Victory Day’ – the day when former East Pakistan seceded from West Pakistan. At the same time for Pakistan, this very date – mainly associated with ‘Fall of Dhaka’ – turns out to be a painful reminder of the surrender of eastern part of the country. In this regard, a lot has been discussed, written and published from time to time. But there are still many significant aspects which remain untold to date, or we can say are lesser known due to certain reasons which have made it hard for Pakistan to tell the world things which are not only factual but are quite contradictory to the widely known narrative that had been adopted globally.

Though there is no denying that the case of East Pakistan was mishandled and mismanaged at various fronts by our own leadership, but to blame them for the entire Bangladesh episode is a highly illogical thing to do. Unfortunately, today, that is exactly what most of our so-called intellectuals do; which only proves that either they are ignorant of the complete history or deliberately intend to keep themselves from presenting the facts.

A renowned journalist of his time and a social worker, Qutubuddin Aziz, has documented in his book ‘Blood & Tears’ – which was published in 1974 – agonizing eye-witness accounts of atrocities committed on non-Bengalis in East Pakistan in 1971. The book provides insights to many questions e.g. I have been hearing from my elders here in (West) Pakistan that they never got to know about the severity of the East Pakistan issue back in 1970-71. The reason is well described in the following passage of ‘Blood & Tears’ where the author says:

“When I remonstrated with the Information Ministry official that it was unethical to clamp a blackout on the news, he explained that press reporting of the killing of non-Bengalis in East Pakistan would unleash serious repercussions in West Pakistan and provoke reprisals against the Bengalis residing in the western wing of the country.”

In order to maintain law and order in the western part, the incidents were never reported in true sense. Besides, strong efforts were made by the rebels in East Pakistan to make sure that the true condition of the region remained unnoticed and not reported by anyone outside East Pakistan. As the author narrates:

“The Awami League militants had gained control over the telecommunications network in East Pakistan during the 1st few days of their uprising and they showed meticulous care in excising even the haziest mention of the massacre of non-Bengalis in press and private telegrams to West Pakistan and the overseas world.”

“A British press correspondent, who was in Dacca in March 1971, told me that a Bengali telephone operator cut off his long-distance conversation with his newspaper colleague in New Delhi in the 3rd week of the month [of march 1971] the moment he made mention of the blood-chilling massacre of non-Bengalis all over the province.”

Hence, a deliberate strategy was implemented to ensure that only the narrative acceptable to India and Awami League rebels was circulated across the globe.

“India’s well-organized propaganda machinery and liberally financed Indian Lobby in the United States were working in top gear to malign Pakistan and to smear the name of the Pakistan Army by purveying yarns of its alleged brutality in East Pakistan.”

Attempts were made to make the international media believe that the genocide was undertaken by Pakistani Army and not the Mukti Bahini and other rebels associated with the Awami League:

“Indian propagandists dished out to foreign correspondents in New Delhi pictures of burnt houses and razed market places as evidence of the devastation caused by the Pakistan Army in East Pakistan although in reality most of the destruction was caused by the well-armed Bengali rebels when they went on the rampage against the non-Bengalis in a bloody and flaming spree of loot, arson and murder. Some pictures were claimed to be of Bengali female victims of the Pakistan Army’s alleged atrocity; a close look at the physical features and dresses of the pictured females disclosed that they were West Pakistanis, not Bengalis.”

Mr. Aziz also mentioned comments of the then Chairman of India’s Institute of Public Affairs, R. R. Kapur that he made in the mid of 1971 (before the fall of Dhaka) explaining why India was fully supporting Sheikh Mujib-ur-Rehman and his secession plan:

“Our support to Mujibur Rehman is based, let us be candid enough, on our sub-conscious hate complex of Pakistan. Platonically, we may plead all virtue but the harsh reality is that Pakistan was wrested from us, and its basis – Two Nation Theories – has never been palatable to us. If something ever happens which proves the unsoundness of that theory, it will be a matter of psychological satisfaction to us. That is, by and large, our national psyche and it is in that context that we have reacted to a happening which, we think, may well disrupt Pakistan.”

The psychological satisfaction which Mr. Kapur talked about was very well reflected in Indira Gandhi’s words later after the fall of Dhaka when she categorically stated; “Today we have taken the revenge of the one thousand years slavery and the birth of Bangladesh is the death of Two Nation Theory”.

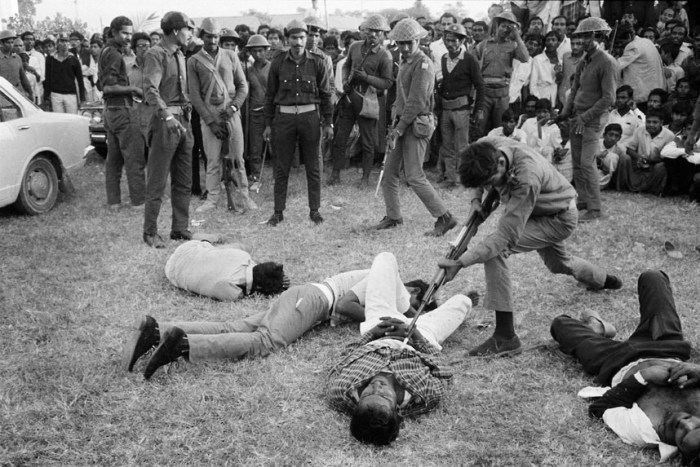

(In picture: Mukti Bahini in action against pro-Pakistanis at the execution ground in Dhaka – 18 December, 1971 – while their accomplices watch the butchery with sadist pleasure. Photo taken by a foreign press photographer)

The facts revealed in ‘Blood and Tears’ have hardly been a matter of discussion till date. The same people who solely blame Pakistan for the 1971 episode remain criminally silent over India’s involvement in the entire crisis. No one dares to talk about the Agartala Conspiracy of 1968 in which the separation plan was devised by Mujibur Rehman long before the 1971 events. Matiur Rahman of Bangladesh explained Sheikh Mujibur Rehman’s actions as follows:

“Mujib’s plea of taking up arms against the government in the face of intolerable political persecution and economic exploitation was an utter lie that has no parallel. A greater lie could not have been invented nor could a greater falsehood be imagined by anyone conversant with facts.”

It pretty much clarifies that the independence of Bangladesh was more than just the result of alleged oppression and atrocities of West Pakistan on that side. Still, why some of our own people remain all focused towards holding Pakistan accountable has been well described by an ex-KGB agent in following words who was present in East Pakistan during 1971:

“These professors and civil rights activists; they are instrumental in the process of the subversion only to destabilize the [Pakistani] nation”

Sarmila Bose – a British academic of Indian origin – who authored ‘Dead Reckoning: Memories of the 1971 Bangladesh War’, challenged the Indo-Bangla narrative on 1971 events. During an interview about her book she mentioned:

“I myself grew up with this Indo-Bangladeshi dominant narrative. I myself did not know when I started this research that I would hear a different story. I didn’t know that… It’s only after I started doing the research I found out what people were telling me; the story that was emerging from the ground was rather different from the dominant narrative that I had grown up with. And I had difficulty accepting that myself…”

These words of a researcher who made an attempt to conduct a dispassionate research speak volumes. The unfortunate part is that the lies associated with the independence of Bangladesh are so deep-rooted that whoever dares to challenge the Indian and Bangladeshi narrative is turned controversial; the latest case being that of the British journalist, David Bergman, who has recently been convicted for questioning Bangladesh’s war death toll. No wonder, even after so many years, the Bangladesh government run by the daughter of Sheikh Mujibur Rehman is still hell-bent towards punishing the pro-Pakistanis. To talk of the condition of those people who are stuck there as ‘stranded Pakistanis’ is another story.

Note: This post originally appeared here

Have to read more on the subject. Bookmarking this post.

LikeLike

Sure!

LikeLike

Nice Piece of Information!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Insightful

LikeLiked by 1 person