This 'workaholic' emperor was hiding a tumultuous private life

Franz Josef's disciplined approach served him well as ruler of Austria-Hungary yet failed to control his rebellious children and beautiful wife Sisi.

On November 30, 1916, with World War I still raging, the people of Vienna poured into the streets to pay their last respects to Franz Josef I, who had been their emperor for 68 years. His death ended a long chapter in Austrian history, remembered now for its glorious waltzes, composers, and art. Vienna had been the capital of an empire that governed the destinies of half of Europe, an empire whose days were numbered.

Franz Josef ’s diligent leadership brought his empire great stability, but his personal life proved far more turbulent over the course of his long life. Beloved by his people, the emperor struggled to connect and direct the relationships within his own family.

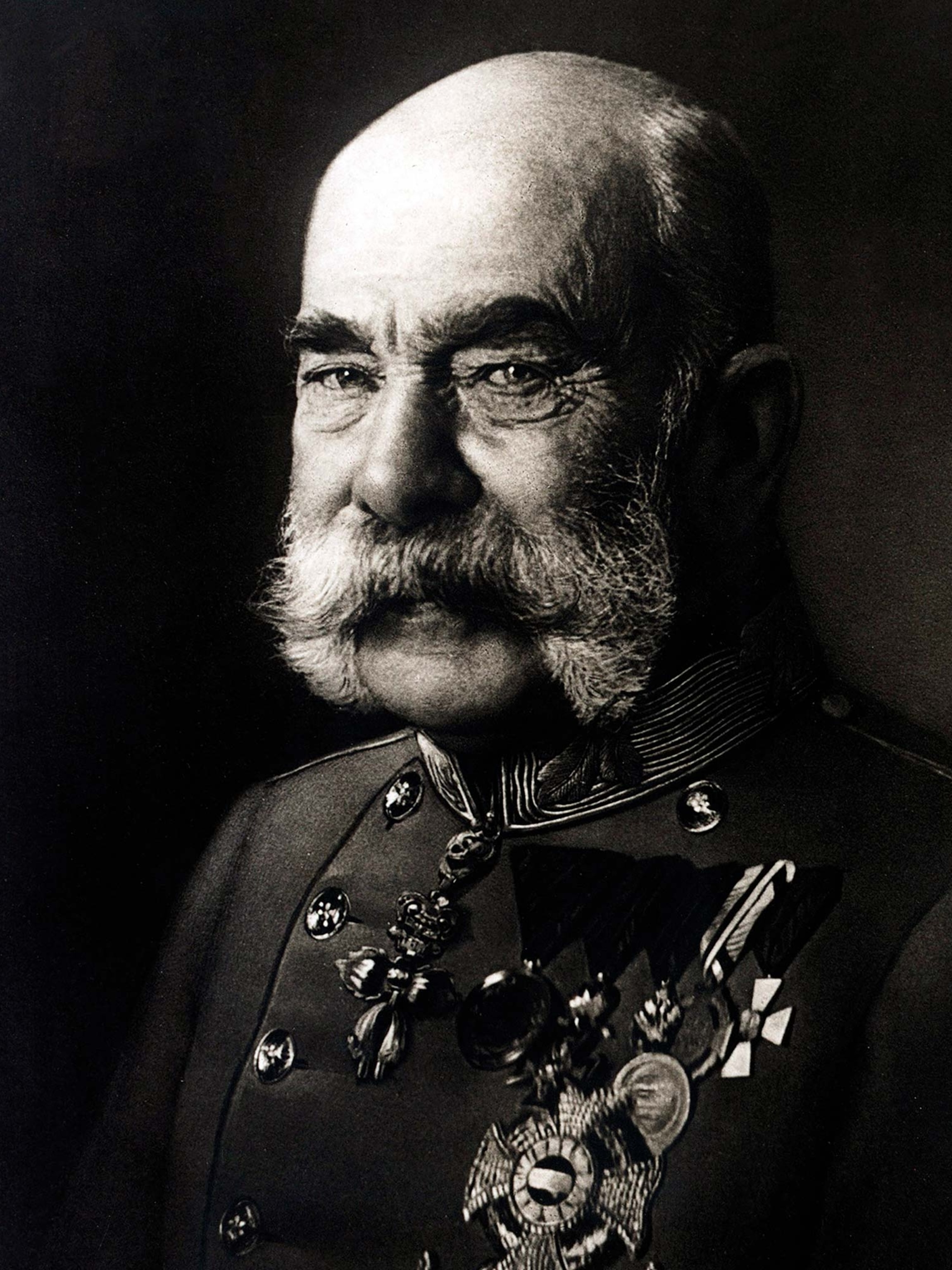

The imperial look

Heir to the empire

August 18, 1830, was a day of great celebration in Austria. The House of Habsburg had been long awaiting the birth of a male heir to the inherit the throne. On that day, young Franz Josef was born to Archduke Franz Karl and his wife, Sophie of Bavaria.

From the beginning, Franz Josef was adored by his mother, who would be a constant controlling presence in his life. The archduchess meticulously recorded the baby’s every milestone. Obsessed with preparing him for the throne, Sophie, along with State Chancellor Prince Klemens von Metternich, designed Franz Josef’s education, preparing a rigorous regimen of classroom study as well as physical education with a strong military discipline throughout.

When Franz Josef became emperor at age 18, Sophie’s influence over her son did not wane. His youth and inexperience made him all the more dependent on his strong-willed mother. Many historians believe that in the early years of his reign, Sophie was a so-called secret empress, setting the political agenda from behind the scenes.

(This colorful map held a secret plea for peace to the Habsburg Empire.)

Marriage plans

Unsurprisingly, Sophie was instrumental in deciding whom Franz Josef would marry. For political reasons, she wanted to strengthen ties between Austria and Germany, and she looked no further than her own family in Bavaria for a bride. Sophie’s sister, Maria Ludovika, had daughters who fit the bill.

The original orchestrated match was supposed to be between 23-year-old Franz and his cousin Helene, but Franz Josef instead fell for Helene’s younger sister, Elisabeth, nicknamed Sisi. She was just 15 but captivated him from their first meeting. They married in 1854.

(Life for Sisi the Bavarian princess was no fairy tale.)

Little did Franz Josef know that he would forever be overshadowed by his wife. He loved Sisi dearly but never really understood her. Franz Josef was generally conservative and methodical, an authoritarian in government but passive in the private sphere. Sisi of Wittelsbach was his polar opposite—liberal, intellectual, and refined. But, despite their differences, they ended up forming a strong and long-lasting relationship.

Empress Sisi

The early years of their marriage were difficult, as the suffocating etiquette of the Viennese court troubled Sisi. Franz Josef, meanwhile, remained under the influence of his mother. Sophie, who gained the reputation of being “the only man”at court, strove to “educate” her young daughter-in-law into becoming what she regarded as a worthy empress.

Franz Josef became caught in a cross fire between the two women in his life. Sophie’s over-bearing presence put the marriage under immense strain. Sisi, troubled and depressed by the situation, spent long periods away from the court to escape her mother-in-law. These absences meant being apart from Franz Josef, too. There were rumors of marital infidelity on the part of the emperor. But despite the turmoil, Franz Josef seemed to love his wife deeply, tolerating her often extravagant whims and accepting her long trips away from Vienna.

The emperor kept a grueling schedule, which may have had roots in his mother’s teachings and his strong Catholic faith. He attended Mass daily, whether in Vienna or away on campaigns. Apart from family lunches and dinners, these services were the only breaks he allowed himself during a workday. Locked away in his official apartments, Franz Josef would meet with his ministers in the morning and answer correspondence or go over documents in the afternoon. Such was his devotion to work that even during his honeymoon, he left Sisi alone at Schönbrunn Palace while he returned to his apartments to take care of state affairs.

That said, he wasn’t a natural bureaucrat and was more at home in a military environment. Since boyhood he had thought of himself as a soldier, and the military structures he knew so well gave him a thoughtful and disciplined, even stoic, temperament. His strict sense of duty was already evident when, on his 15th birthday, he wrote in his diary: “There is little time left to finish my education, so I have to work hard to improve.”

The emperor's affairs

Parenting problems

Despite the physical distance that characterized a large part of their marriage, Franz Josef and Sisi had four children: Sophia (who died at age two), Gisela, Rudolf, and Marie Valerie. At first, Sisi felt as though motherhood was being thrust upon her; before the age of 21, she had borne three children. The upbringing of the royal children only increased the tension between Franz Josef’s mother and bride. Sophie believed her daughter-in-law to be incapable of caring for the small children and took over their upbringing and care. Sisi withdrew more and more from court life to escape Sophie’s expectations, which also distanced her from her family.

The emperor had a close and loving relationship with his daughters. The youngest one, Marie Valerie, left a diary, a priceless source of insights into their family life. In it she portrays Franz Josef as an endearing father and, later, grandfather. Perhaps the only notable conflicts arose when the royal daughters were to be married.

Archduchess Gisela was only 15 when she sought to marry Leopold of Bavaria. Marie Valerie rejected her father’s choice of the Duke of Braganza, heir to Saxony, preferring Archduke Francisco Salvador of Austria-Tuscany. But despite Franz Josef’s initial opposition to his daughters’ choices of marriage partners, Sisi intervened on their behalf. The empress’s influence won out in the end, and Franz Josef relented on both counts.

The relationship between father and son was far more complicated. The emperor hoped Rudolf would be raised in the same fashion as he had, with an emphasis on military discipline, obedience, and Catholic virtue. Sisi, who had been away from court during the boy’s early years, returned and was horrified by the harsh education her husband was inflicting on their son. The emperor believed Rudolf was too sensitive and in need of toughening up. Sisi intervened, going as far as threatening to leave her husband if these methods did not change. The emperor, still madly in love with his wife, relented despite the scandal it caused.

The Mayerling incident

But Franz Josef’s attitude toward Rudolf did not abate as the boy grew up. He continued to believe his heir lacked the qualities essential for an emperor. In his father’s opinion, Rudolf had no interest in the military, was lax in his Catholic observance, and carried on flagrant love affairs. Rudolf did seek out his father’s approval but never obtained it; he felt his father ignored his suggestions and ideas.

The pair’s relationship came to a tragic end after Franz Josef forced Rudolf into marrying Princess Stéphanie of Belgium in 1881. Their union was politically advantageous but turned out to be a disastrous mismatch. Rudolf had countless extramarital affairs, much to the dismay of his wife and his father.

On January 30, 1889, the day after father and son had a bitter argument, Rudolf and his lover Mary Vetsera were found dead at a hunting lodge in Mayerling, victims of an apparent murder-suicide. Faced with a scandal, Franz Josef tried to cover up the true circumstances surrounding their deaths but was forced to publicly acknowledge that the crown prince had ended his own life.

Troubled times

His son’s tragic death would not be the end of personal traumas for Franz Josef. In 1898 he lost his beloved wife. The relationship between the two had been strained, but the loss was devastating to Franz Josef nonetheless. An Italian anarchist named Luigi Lucheni stabbed and killed Sisi in Geneva. According to Marie Valerie’s diary, Franz Josef locked himself in a cold silence after the death of the empress.

After the death of his heir, the line of succession moved to Franz Josef’s brother’s family. The imperial government continued to promote a public image of Franz Josef as a good-natured Austrian grandfather who loved his country, which resonated strongly with his Austrian subjects. Photographs of the emperor hunting or hiking appeared in the newspapers at moments of national crisis.

Family tragedy struck again in 1914, when Franz Josef’s nephew and successor, Franz Ferdinand, was assassinated in Sarajevo. This act caused Franz Josef to declare war on Serbia, one of a series of events that set off the cataclysm of World War I. Franz Josef committed himself to war even though he sensed that this could be the end of his empire. On November 21, 1916, he woke up with a fever, but nevertheless insisted on going to Mass and dispatching affairs of state. That afternoon he passed away. Death saved him from witnessing the end of an empire to which he had devoted his life.

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?

- This ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thoughtThis ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thought

- Why this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect senseWhy this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect sense

- When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

Environment

- Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?

- The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

History & Culture

- Meet the original members of the tortured poets departmentMeet the original members of the tortured poets department

- Séances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occultSéances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occult

- Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?

- Beauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century SpainBeauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century Spain

Science

- Here's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in spaceHere's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in space

- Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.

- NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

Travel

- This tomb diver was among the first to swim beneath a pyraamidThis tomb diver was among the first to swim beneath a pyraamid

- Dina Macki on Omani cuisine and Zanzibari flavoursDina Macki on Omani cuisine and Zanzibari flavours

- How to see Mexico's Baja California beyond the beachesHow to see Mexico's Baja California beyond the beaches

- Could Mexico's Chepe Express be the ultimate slow rail adventure?Could Mexico's Chepe Express be the ultimate slow rail adventure?