-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Magdalena Leszko, Ludmila Zając-Lamparska, Janusz Trempala, Aging in Poland, The Gerontologist, Volume 55, Issue 5, October 2015, Pages 707–715, https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnu171

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

With 38 million residents, Poland has the eighth-largest population in Europe. A successful transition from communism to democracy, which began in 1989, has brought several significant changes to the country’s economic development, demographic structure, quality of life, and public policies. As in the other European countries, Poland has been facing a rapid increase in the number of older adults. Currently, the population 65 and above is growing more rapidly than the total population and this discrepancy will have important consequences for the country’s economy. As the population ages, there will be increased demands to improve Poland’s health care and retirement systems. This article aims to provide a brief overview of the demographic trends in Poland as well a look at the country’s major institutions of gerontology research. The article also describes key public policies concerning aging and how these may affect the well-being of Poland’s older adults.

The Demographics of Aging in Poland

According to estimates produced by the Polish Central Statistical Office, at the end of 2013 Poland had a population of 38.5 million individuals, of whom 48% were men and 52% were women ( Polish Central Statistical Office, 2011 ). However, it is projected that the population will decrease to 32 million by 2050. One of the two main reasons for this population decrease is emigration. Since Poland’s accession to the European Union in 2004, significant numbers have emigrated, mainly to the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland, in search of greater financial security. Another reason for Poland’s population decline is a low birth rate ( Table 1 ). Before the transformation from a communist to a capitalist economy, Poland witnessed relatively high fertility. Total fertility rates have declined from 3.7 children per woman in the 1950s to an estimated 1.32 children per woman in 2014, well under the population replacement rate of 2 children per woman. These demographic trends suggest major changes to Poland’s socioeconomic structure.

Population Indicators and Projections for Poland

| . | Population (in millions) . | Growth rate (%) . | Fertility rate a . | Life expectancy (in years) . | Median age (in years) . | Proportion of elderly population (%) b . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1950 | 24.8 | 1.7 | 3.7 | 58.8 | 25.8 | 5.3 |

| 1960 | 29.6 | 1.1 | 2.9 | 67.7 | 26.7 | 5.9 |

| 1970 | 32.7 | 0.8 | 2.2 | 69.9 | 28.3 | 8.4 |

| 1980 | 35.6 | 0.9 | 2.4 | 70.1 | 29.7 | 10.0 |

| 1990 | 38.1 | 0.2 | 2.0 | 70.7 | 32.3 | 10.2 |

| 2000 | 28.4 | 0.0 | 1.4 | 73.8 | 35.4 | 12.4 |

| 2010 | 38.0 | 0.1 | 1.4 | 76.4 | 28.1 | 13.5 |

| 2020 | 37.4 | 1.3 | 78.1 | 22 | ||

| 2030 | 36.7 | 1.3 | 79.2 | 27 |

| . | Population (in millions) . | Growth rate (%) . | Fertility rate a . | Life expectancy (in years) . | Median age (in years) . | Proportion of elderly population (%) b . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1950 | 24.8 | 1.7 | 3.7 | 58.8 | 25.8 | 5.3 |

| 1960 | 29.6 | 1.1 | 2.9 | 67.7 | 26.7 | 5.9 |

| 1970 | 32.7 | 0.8 | 2.2 | 69.9 | 28.3 | 8.4 |

| 1980 | 35.6 | 0.9 | 2.4 | 70.1 | 29.7 | 10.0 |

| 1990 | 38.1 | 0.2 | 2.0 | 70.7 | 32.3 | 10.2 |

| 2000 | 28.4 | 0.0 | 1.4 | 73.8 | 35.4 | 12.4 |

| 2010 | 38.0 | 0.1 | 1.4 | 76.4 | 28.1 | 13.5 |

| 2020 | 37.4 | 1.3 | 78.1 | 22 | ||

| 2030 | 36.7 | 1.3 | 79.2 | 27 |

Note: Polish Central Statistical Office projections for the period 2008–2035.

a The average number of children that a woman can expect to bear during her lifetime.

b The number of individuals aged 65 and older as a percentage of the total population.

Population Indicators and Projections for Poland

| . | Population (in millions) . | Growth rate (%) . | Fertility rate a . | Life expectancy (in years) . | Median age (in years) . | Proportion of elderly population (%) b . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1950 | 24.8 | 1.7 | 3.7 | 58.8 | 25.8 | 5.3 |

| 1960 | 29.6 | 1.1 | 2.9 | 67.7 | 26.7 | 5.9 |

| 1970 | 32.7 | 0.8 | 2.2 | 69.9 | 28.3 | 8.4 |

| 1980 | 35.6 | 0.9 | 2.4 | 70.1 | 29.7 | 10.0 |

| 1990 | 38.1 | 0.2 | 2.0 | 70.7 | 32.3 | 10.2 |

| 2000 | 28.4 | 0.0 | 1.4 | 73.8 | 35.4 | 12.4 |

| 2010 | 38.0 | 0.1 | 1.4 | 76.4 | 28.1 | 13.5 |

| 2020 | 37.4 | 1.3 | 78.1 | 22 | ||

| 2030 | 36.7 | 1.3 | 79.2 | 27 |

| . | Population (in millions) . | Growth rate (%) . | Fertility rate a . | Life expectancy (in years) . | Median age (in years) . | Proportion of elderly population (%) b . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1950 | 24.8 | 1.7 | 3.7 | 58.8 | 25.8 | 5.3 |

| 1960 | 29.6 | 1.1 | 2.9 | 67.7 | 26.7 | 5.9 |

| 1970 | 32.7 | 0.8 | 2.2 | 69.9 | 28.3 | 8.4 |

| 1980 | 35.6 | 0.9 | 2.4 | 70.1 | 29.7 | 10.0 |

| 1990 | 38.1 | 0.2 | 2.0 | 70.7 | 32.3 | 10.2 |

| 2000 | 28.4 | 0.0 | 1.4 | 73.8 | 35.4 | 12.4 |

| 2010 | 38.0 | 0.1 | 1.4 | 76.4 | 28.1 | 13.5 |

| 2020 | 37.4 | 1.3 | 78.1 | 22 | ||

| 2030 | 36.7 | 1.3 | 79.2 | 27 |

Note: Polish Central Statistical Office projections for the period 2008–2035.

a The average number of children that a woman can expect to bear during her lifetime.

b The number of individuals aged 65 and older as a percentage of the total population.

According to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Poland has one of the lowest life expectancies at birth among European Union countries. The average life expectancy in 2014 was 77 years overall (81 years for women compared with 73 years for men; Central Intelligence Agency World Factbook, 2014 ).

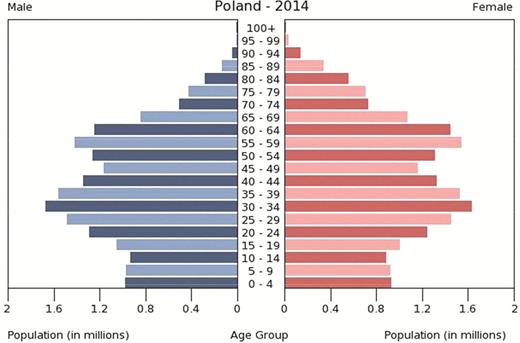

Similar to other European countries, Poland’s population is aging ( Figure 1 ). The median age increased from 28.8 years in 1950 to 38.5 in 2012 and it is projected to further increase to 51 years by 2050 ( Devictor, 2012 ). The population more than 65 years of age represents 13.5% of the total population in 2010. Although the number of people aged 65 and older in Poland is lower than the European average (17%) ( Eurostat, 2013 ), this percentage in Poland is expected to increase slowly but steadily so that by 2030, 27% of the population is projected to be 65 or older. Figure 1 demonstrates Poland’s current age pyramid. Similar to other countries, there is a gender imbalance at older ages. As a result of lower female mortality rates, almost 60% of older adults aged 70–74 years are female and this proportion gradually increases to 76% for those 90–94 years.

Age and gender structure of Poland, 2014. Source : U.S. Census Bureau, International Data Base.

Before World War II Poland was populated by diverse ethnicities, however, recent estimates shows that 96.7% of the people of Poland claimed polish nationality. The country is also uniform in term of religion, the majority of the polish population (95%) is Roman Catholic ( Polish Central Statistical Office, 2013 ).

Gerontological Research in Poland

In Poland, interest in gerontological research began later than in other Western countries, perhaps due to the political and economic challenges that the country was facing shortly after World War II. The first Polish publication in gerontology was written by Józef Mruk (1946), which was entitled Zmiany nadnerczy w wieku starczym ( Changes in the adrenal glands in old age ) and the first national gerontological study of a representative sample of 2,714 people was conducted between 1966 and 1967 by a team from the School of Planning and Statistics in Warsaw under the direction of Jerzy Piotrowski (1973) .

Currently three Polish-language scientific journals publish research on aging and old age: Gerontolgia Polska ( Polish Gerontology , established in 1993), Polish Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry (established in 1998), and Geriatria ( Geriatrics, established in 2007). Although interest in gerontological research has been steadily increasing with the establishment of these journals, the number of publications written in Polish, and listed in Medline under the entry “elderly,” has not increased since the 1990s. Polish authors have opted to publish in English due to their increasing participation in international research teams ( Derejczyk, Bień, Kokoszka-Paszkot, & Szczygiel, 2008 ).

There are no government or private institutions that specialize in financing gerontololgical research. However, in recent years, there has been an increase in the number of grants in the field of gerontology due to competitions funded by the National Science Center and the National Research and Development Centre. Research on aging is also funded by local governments, such as cities, within the framework of programs to promote human resources, health, and social welfare. Table 2 presents the country’s major gerontological research institutions and their particular research interests.

Major Institutions in Gerontology in Poland

| Institution . | Person . | Area of research . | How to access . |

|---|---|---|---|

| International Institute of Molecular and Cell Biology in Warsaw (IIMCB) in Warsaw | Jacek Kuźnicki, Małgorzata Mossakowska, Aleksandra Szybalska, Aleksandra Szybińska Emilia Bialopiotrowicz | The main objectives of the Institute are basic research in the field of molecular medicine: mechanisms of carcinogenesis and aging, the molecular basis of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson diseases, resistance to antibiotics, immunology, and repair of the genome. | http://www.iimcb.gov.pl/ |

| Nencki Institute of Experimental Biology (NIEB) in Warsaw | Ewa Sikora, Anna Bielak- Żmijewska, Grażyna Mosieniak | Institute research focuses on the mechanisms of cell cycle regulation, cellular senescence and cell death of primary, immortalized and cancer cells. For example, the role of apoptosis and autophagy in cellular senescence, organismal aging and immunosenescence, markers possibly determining healthy ageing and longevity. | http://en.nencki.gov.pl/laboratory- of-molecular-bases-of-aging |

| Healthy Ageing Research Center (HARC) in Lodz | Marek Kowalski, Tomasz Kostka, Beata Sikorska, Wojciech Piotrowski, Jolanta Niewiarowska, Iwona Kloszewska, Tomasz Sobów, Paweł Górski, Jacek Rysz, Maciej Banach | The Center engages in research on the quality of life, neurodegenerative diseases, resistance to infections in respiratory diseases, cardiovascular and renal function, and cell aging. | http://harc.umed.pl/ |

| Interdisciplinary Center for Applied Cognitive Studies (ICACS) in Warsaw | Grzegorz Sędek, Rafał Albiński, Aneta Brzezicka, Izabela Krejtz, Kinga Piber-Dąbrowska, Szymon Wichary | The Center is focused on theoretical and applied interdisciplinary research, particularly in the area of cognitive aging and senile depression, but also on stereotyping and prejudice against the elderly. | http://www.icacs.swps.edu.pl/icacs/ |

| Institute of Public Affairs (ISP) in Warsaw | Piotr Szukalski, Iwona Oliwińska, Elżbieta Bojanowska, Iwona Oliwińska, Janusz Halik | The Institute focuses on selected elements of the life style of older people, their health and disability, the use of rehabilitation, their plans for withdrawal from the labor market and the factors affecting these plans. | http://www.zus.pl/files/ dpir/20080930_To_idzie_starosc_ polityka_spoleczna_wobec_procesu_starzenia.pdf |

| Institution . | Person . | Area of research . | How to access . |

|---|---|---|---|

| International Institute of Molecular and Cell Biology in Warsaw (IIMCB) in Warsaw | Jacek Kuźnicki, Małgorzata Mossakowska, Aleksandra Szybalska, Aleksandra Szybińska Emilia Bialopiotrowicz | The main objectives of the Institute are basic research in the field of molecular medicine: mechanisms of carcinogenesis and aging, the molecular basis of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson diseases, resistance to antibiotics, immunology, and repair of the genome. | http://www.iimcb.gov.pl/ |

| Nencki Institute of Experimental Biology (NIEB) in Warsaw | Ewa Sikora, Anna Bielak- Żmijewska, Grażyna Mosieniak | Institute research focuses on the mechanisms of cell cycle regulation, cellular senescence and cell death of primary, immortalized and cancer cells. For example, the role of apoptosis and autophagy in cellular senescence, organismal aging and immunosenescence, markers possibly determining healthy ageing and longevity. | http://en.nencki.gov.pl/laboratory- of-molecular-bases-of-aging |

| Healthy Ageing Research Center (HARC) in Lodz | Marek Kowalski, Tomasz Kostka, Beata Sikorska, Wojciech Piotrowski, Jolanta Niewiarowska, Iwona Kloszewska, Tomasz Sobów, Paweł Górski, Jacek Rysz, Maciej Banach | The Center engages in research on the quality of life, neurodegenerative diseases, resistance to infections in respiratory diseases, cardiovascular and renal function, and cell aging. | http://harc.umed.pl/ |

| Interdisciplinary Center for Applied Cognitive Studies (ICACS) in Warsaw | Grzegorz Sędek, Rafał Albiński, Aneta Brzezicka, Izabela Krejtz, Kinga Piber-Dąbrowska, Szymon Wichary | The Center is focused on theoretical and applied interdisciplinary research, particularly in the area of cognitive aging and senile depression, but also on stereotyping and prejudice against the elderly. | http://www.icacs.swps.edu.pl/icacs/ |

| Institute of Public Affairs (ISP) in Warsaw | Piotr Szukalski, Iwona Oliwińska, Elżbieta Bojanowska, Iwona Oliwińska, Janusz Halik | The Institute focuses on selected elements of the life style of older people, their health and disability, the use of rehabilitation, their plans for withdrawal from the labor market and the factors affecting these plans. | http://www.zus.pl/files/ dpir/20080930_To_idzie_starosc_ polityka_spoleczna_wobec_procesu_starzenia.pdf |

Major Institutions in Gerontology in Poland

| Institution . | Person . | Area of research . | How to access . |

|---|---|---|---|

| International Institute of Molecular and Cell Biology in Warsaw (IIMCB) in Warsaw | Jacek Kuźnicki, Małgorzata Mossakowska, Aleksandra Szybalska, Aleksandra Szybińska Emilia Bialopiotrowicz | The main objectives of the Institute are basic research in the field of molecular medicine: mechanisms of carcinogenesis and aging, the molecular basis of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson diseases, resistance to antibiotics, immunology, and repair of the genome. | http://www.iimcb.gov.pl/ |

| Nencki Institute of Experimental Biology (NIEB) in Warsaw | Ewa Sikora, Anna Bielak- Żmijewska, Grażyna Mosieniak | Institute research focuses on the mechanisms of cell cycle regulation, cellular senescence and cell death of primary, immortalized and cancer cells. For example, the role of apoptosis and autophagy in cellular senescence, organismal aging and immunosenescence, markers possibly determining healthy ageing and longevity. | http://en.nencki.gov.pl/laboratory- of-molecular-bases-of-aging |

| Healthy Ageing Research Center (HARC) in Lodz | Marek Kowalski, Tomasz Kostka, Beata Sikorska, Wojciech Piotrowski, Jolanta Niewiarowska, Iwona Kloszewska, Tomasz Sobów, Paweł Górski, Jacek Rysz, Maciej Banach | The Center engages in research on the quality of life, neurodegenerative diseases, resistance to infections in respiratory diseases, cardiovascular and renal function, and cell aging. | http://harc.umed.pl/ |

| Interdisciplinary Center for Applied Cognitive Studies (ICACS) in Warsaw | Grzegorz Sędek, Rafał Albiński, Aneta Brzezicka, Izabela Krejtz, Kinga Piber-Dąbrowska, Szymon Wichary | The Center is focused on theoretical and applied interdisciplinary research, particularly in the area of cognitive aging and senile depression, but also on stereotyping and prejudice against the elderly. | http://www.icacs.swps.edu.pl/icacs/ |

| Institute of Public Affairs (ISP) in Warsaw | Piotr Szukalski, Iwona Oliwińska, Elżbieta Bojanowska, Iwona Oliwińska, Janusz Halik | The Institute focuses on selected elements of the life style of older people, their health and disability, the use of rehabilitation, their plans for withdrawal from the labor market and the factors affecting these plans. | http://www.zus.pl/files/ dpir/20080930_To_idzie_starosc_ polityka_spoleczna_wobec_procesu_starzenia.pdf |

| Institution . | Person . | Area of research . | How to access . |

|---|---|---|---|

| International Institute of Molecular and Cell Biology in Warsaw (IIMCB) in Warsaw | Jacek Kuźnicki, Małgorzata Mossakowska, Aleksandra Szybalska, Aleksandra Szybińska Emilia Bialopiotrowicz | The main objectives of the Institute are basic research in the field of molecular medicine: mechanisms of carcinogenesis and aging, the molecular basis of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson diseases, resistance to antibiotics, immunology, and repair of the genome. | http://www.iimcb.gov.pl/ |

| Nencki Institute of Experimental Biology (NIEB) in Warsaw | Ewa Sikora, Anna Bielak- Żmijewska, Grażyna Mosieniak | Institute research focuses on the mechanisms of cell cycle regulation, cellular senescence and cell death of primary, immortalized and cancer cells. For example, the role of apoptosis and autophagy in cellular senescence, organismal aging and immunosenescence, markers possibly determining healthy ageing and longevity. | http://en.nencki.gov.pl/laboratory- of-molecular-bases-of-aging |

| Healthy Ageing Research Center (HARC) in Lodz | Marek Kowalski, Tomasz Kostka, Beata Sikorska, Wojciech Piotrowski, Jolanta Niewiarowska, Iwona Kloszewska, Tomasz Sobów, Paweł Górski, Jacek Rysz, Maciej Banach | The Center engages in research on the quality of life, neurodegenerative diseases, resistance to infections in respiratory diseases, cardiovascular and renal function, and cell aging. | http://harc.umed.pl/ |

| Interdisciplinary Center for Applied Cognitive Studies (ICACS) in Warsaw | Grzegorz Sędek, Rafał Albiński, Aneta Brzezicka, Izabela Krejtz, Kinga Piber-Dąbrowska, Szymon Wichary | The Center is focused on theoretical and applied interdisciplinary research, particularly in the area of cognitive aging and senile depression, but also on stereotyping and prejudice against the elderly. | http://www.icacs.swps.edu.pl/icacs/ |

| Institute of Public Affairs (ISP) in Warsaw | Piotr Szukalski, Iwona Oliwińska, Elżbieta Bojanowska, Iwona Oliwińska, Janusz Halik | The Institute focuses on selected elements of the life style of older people, their health and disability, the use of rehabilitation, their plans for withdrawal from the labor market and the factors affecting these plans. | http://www.zus.pl/files/ dpir/20080930_To_idzie_starosc_ polityka_spoleczna_wobec_procesu_starzenia.pdf |

Polish researchers are involved with a variety of European research projects. For example, the Nencki Institute for Experimental Biology (NIEB) participated in the Genetics of Healthy Aging (GEHA) project involving 11 European countries. This project has identified four chromosome regions linked to human longevity: 14q11.2, 17q12-q22, 19p13.3-p13.11, and 19q13.11-q13.32. In addition, three sex-specific loci were also linked to longevity in a sex-specific manner: 8p11.21-q13.1 (men), 15q12-q14 (women), and 19q13.33-q13.41 (women). Further analysis showed that genetic variation at the APOE gene locus was significantly associated with longevity ( Beekman et al., 2013 ).

A prominent focus of the Interdisciplinary Center for Applied Cognitive Studies (ICACS) research program is cognitive aging. Sedek with collaborators from other countries focuses on the nature of age-related limitations in solving complex tasks, as well as on possible coping and compensatory mechanisms (e.g., Sedek, Verhaeghen, & Martin, 2013 ; Sedek & von Hecker, 2004 ). One interesting result is an interaction between task modality and participant age for the simple transitive reasoning. For example, young adults performed best when given abstract visual tasks, which include conditions such as B < A and C > A, requiring to combine these conditions for inferences about the relationships between components (i.e., C is the biggest) whereas older adults performed best when the reasoning task was presented as auditorally as a short narrative (e.g., short story about three girls, which included the height relationship between them, in addition to many other information, irrelevant to the task itself). Sedek and colleagues (2013) suggests that these findings indicate that traditional fluid intelligence tests (e.g., Wechsler or Ravens tests) which include abstract reasoning tasks may grossly underestimate the reasoning abilities of older adults.

There are no Polish databases of longitudinal studies on aging. Studies conducted in Poland are usually cross-sectional, comparing contemporary cohorts with earlier cohorts ( Ciura & Zgliczyński, 2012 ; Karpiński & Rajkiewicz, 2008 ; Synak, 2002 ), and cross-culturally, comparing Polish elderly with elderly in other countries (e.g. within the framework of the SHARE European Program, see later). Data sets available for secondary analysis are summarized in Table 3 .

Key Research on Aging in Poland

| Title . | Methods . | Description . |

|---|---|---|

| Polish Centenarian Program (PolStu), http:// cent.iimcb.gov.pl/ | A panel survey carried out in 1999 (350 individuals aged range 100–108, median age 100.8) | Describes conditions in which centenarians’ health, education, and lifestyle. |

| Medical, psychological, sociological and economic aspects of elderly in Poland (PolSenior), http://polsenior.iimcb.gov.pl/ home , http://polsenior.iimcb.gov.pl/en/publications/ monograph | A nationally representative survey carried out in 2006 (totaling 5,695 individuals, including 4,979 aged 65+, M = 79.4, SD = 8.69, and 716 individuals between 55 and 59) | Provides data on health and socioeconomic status. Final target is a profile of the needs of aging population to inform social policies and to shape future decision-making in this area. |

| Social activity in the perception of Poles (Social Diagnosis 2013), http://www.diagnoza. com/pliki/raporty_tematyczne/Aktywnosc_ spoleczna_osob_starszych.pdf | A nationally representative survey carried out in 2013 (6,569 individuals in five age ranges: 60–64, N = 2,094; 65–69, N = 1,397; 70–74, N = 1,003; 75–79, N = 1,036; and 80+, N = 1,039) | The aim was to identify factors modifying the behavior of the elderly, to assess their activities within the local community and environment, their needs and expectations, and to determine which elements of their life situation have the greatest influence on these activities. |

| The Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE), http://www.share-project. org/ | Multidisciplinary and cross-national panel survey carried out since 2004 (of >85,000 individuals from 20 European countries, aged 50+). | A free of charge database of data on health and socio-economic status, as well as social and family networks. Poland has joined SHARE in 2006 and participated in the second (2006–2007), third (2008–2009), and forth (2010–2012) waves of data collection (about 3,000 individuals, aged 50+). |

| Title . | Methods . | Description . |

|---|---|---|

| Polish Centenarian Program (PolStu), http:// cent.iimcb.gov.pl/ | A panel survey carried out in 1999 (350 individuals aged range 100–108, median age 100.8) | Describes conditions in which centenarians’ health, education, and lifestyle. |

| Medical, psychological, sociological and economic aspects of elderly in Poland (PolSenior), http://polsenior.iimcb.gov.pl/ home , http://polsenior.iimcb.gov.pl/en/publications/ monograph | A nationally representative survey carried out in 2006 (totaling 5,695 individuals, including 4,979 aged 65+, M = 79.4, SD = 8.69, and 716 individuals between 55 and 59) | Provides data on health and socioeconomic status. Final target is a profile of the needs of aging population to inform social policies and to shape future decision-making in this area. |

| Social activity in the perception of Poles (Social Diagnosis 2013), http://www.diagnoza. com/pliki/raporty_tematyczne/Aktywnosc_ spoleczna_osob_starszych.pdf | A nationally representative survey carried out in 2013 (6,569 individuals in five age ranges: 60–64, N = 2,094; 65–69, N = 1,397; 70–74, N = 1,003; 75–79, N = 1,036; and 80+, N = 1,039) | The aim was to identify factors modifying the behavior of the elderly, to assess their activities within the local community and environment, their needs and expectations, and to determine which elements of their life situation have the greatest influence on these activities. |

| The Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE), http://www.share-project. org/ | Multidisciplinary and cross-national panel survey carried out since 2004 (of >85,000 individuals from 20 European countries, aged 50+). | A free of charge database of data on health and socio-economic status, as well as social and family networks. Poland has joined SHARE in 2006 and participated in the second (2006–2007), third (2008–2009), and forth (2010–2012) waves of data collection (about 3,000 individuals, aged 50+). |

Key Research on Aging in Poland

| Title . | Methods . | Description . |

|---|---|---|

| Polish Centenarian Program (PolStu), http:// cent.iimcb.gov.pl/ | A panel survey carried out in 1999 (350 individuals aged range 100–108, median age 100.8) | Describes conditions in which centenarians’ health, education, and lifestyle. |

| Medical, psychological, sociological and economic aspects of elderly in Poland (PolSenior), http://polsenior.iimcb.gov.pl/ home , http://polsenior.iimcb.gov.pl/en/publications/ monograph | A nationally representative survey carried out in 2006 (totaling 5,695 individuals, including 4,979 aged 65+, M = 79.4, SD = 8.69, and 716 individuals between 55 and 59) | Provides data on health and socioeconomic status. Final target is a profile of the needs of aging population to inform social policies and to shape future decision-making in this area. |

| Social activity in the perception of Poles (Social Diagnosis 2013), http://www.diagnoza. com/pliki/raporty_tematyczne/Aktywnosc_ spoleczna_osob_starszych.pdf | A nationally representative survey carried out in 2013 (6,569 individuals in five age ranges: 60–64, N = 2,094; 65–69, N = 1,397; 70–74, N = 1,003; 75–79, N = 1,036; and 80+, N = 1,039) | The aim was to identify factors modifying the behavior of the elderly, to assess their activities within the local community and environment, their needs and expectations, and to determine which elements of their life situation have the greatest influence on these activities. |

| The Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE), http://www.share-project. org/ | Multidisciplinary and cross-national panel survey carried out since 2004 (of >85,000 individuals from 20 European countries, aged 50+). | A free of charge database of data on health and socio-economic status, as well as social and family networks. Poland has joined SHARE in 2006 and participated in the second (2006–2007), third (2008–2009), and forth (2010–2012) waves of data collection (about 3,000 individuals, aged 50+). |

| Title . | Methods . | Description . |

|---|---|---|

| Polish Centenarian Program (PolStu), http:// cent.iimcb.gov.pl/ | A panel survey carried out in 1999 (350 individuals aged range 100–108, median age 100.8) | Describes conditions in which centenarians’ health, education, and lifestyle. |

| Medical, psychological, sociological and economic aspects of elderly in Poland (PolSenior), http://polsenior.iimcb.gov.pl/ home , http://polsenior.iimcb.gov.pl/en/publications/ monograph | A nationally representative survey carried out in 2006 (totaling 5,695 individuals, including 4,979 aged 65+, M = 79.4, SD = 8.69, and 716 individuals between 55 and 59) | Provides data on health and socioeconomic status. Final target is a profile of the needs of aging population to inform social policies and to shape future decision-making in this area. |

| Social activity in the perception of Poles (Social Diagnosis 2013), http://www.diagnoza. com/pliki/raporty_tematyczne/Aktywnosc_ spoleczna_osob_starszych.pdf | A nationally representative survey carried out in 2013 (6,569 individuals in five age ranges: 60–64, N = 2,094; 65–69, N = 1,397; 70–74, N = 1,003; 75–79, N = 1,036; and 80+, N = 1,039) | The aim was to identify factors modifying the behavior of the elderly, to assess their activities within the local community and environment, their needs and expectations, and to determine which elements of their life situation have the greatest influence on these activities. |

| The Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE), http://www.share-project. org/ | Multidisciplinary and cross-national panel survey carried out since 2004 (of >85,000 individuals from 20 European countries, aged 50+). | A free of charge database of data on health and socio-economic status, as well as social and family networks. Poland has joined SHARE in 2006 and participated in the second (2006–2007), third (2008–2009), and forth (2010–2012) waves of data collection (about 3,000 individuals, aged 50+). |

An analysis of the results of the Institute of Public Affairs’ study of a representative sample of persons aged 45–65 years old showed little active preparation for old age and retirement in Polish society ( Szukalski, 2008 , 2009 ). One of the main conclusions was that older people take limited responsibility for their future and expect that the public pension system will provide for them.

An analysis of a survey carried out in 1999–2001 by the Polish Society of Gerontology found many changes affecting older adults after the political and economic reforms begun in 1989 ( Synak, 2002 , 2003 ). Pensioners’ cost of living increased yet pensions failed to match this increase; pensioners’ largest expenditure is now medicine whereas in the 1960s it was clothing. Housing conditions have improved significantly. There have also been improvements in nursing home care, hospitalization, and social insurance. However, older adults’ self-assessments of their health have declined, perhaps reflecting changes to the traditional model of family care. While intergenerational contacts are still close, families are more likely to provide care and intimacy “at a distance.”

Research by Social Diagnosis 2013 showed that the physical and social activity of respondents aged 60 and older decreases with age. Comparing to younger adults, the elderly spend on average 60% more time watching TV and are twice less likely to play sports (although Nordic walking, running, jogging, or cycling are as popular as with younger group). In addition, older adults were much less likely to go to the movie theater, concert, restaurants, cafe, or pubs and are less likely to participate in social meetings. However, there is a significant relationship between various forms of activity (familial, physical, and social) and educational attainment. For instance, older people having higher education (college degree) show the highest organizational activity (mainly in religious and community organizations, hobby clubs, residents’ committees and universities for the elderly), and the lowest level of passive pastimes, such as watching television. Moreover, although half of elderly individuals are taken care of by domestic co-residents or act as a caregiver for another co-resident (usually for a spouse), their contacts are not limited only to family: only 7.3% of elderly report failure to be in touch with friends and acquaintances, similarly to younger people ( Czapiński, 2013 ; Czapiński & Panek, 2014 ).

Comparative analyses based on SHARE show that Poles aged 50 and older (a) have the lowest level of subjective well-being among the surveyed Europeans and the highest level of affective disorders such as depression and negative affect ( Czapiński, 2009 ; Myck et al., 2009 ); (b) as in other European countries, life satisfaction is enhanced by a life partner, wealth and education, however contrary to Northern (e.g., Denmark, the Netherlands, and Sweden) and Southern European societies (e.g., Italy and Greece), life satisfaction declines with age, for both men and women ( Czapiński, 2009 ); (c) in Poland, similarly to other regions, leaving the labor market by older people, especially women, reflects “push-and-pull” mechanisms. “Pushing” older people from the workplace is the widespread belief that older people should “make room for the young”. ‘Pulling” older people from the workforce is the general expectation that grandparents will help to look after grandchildren ( Krzyżowski, 2011 ). However, in Poland the main reason for the decision to leave the labor market is simply the eligibility for pension. In other words, the decision to retire is typically not related to poor health, but rather due to poor working conditions and inadequate salary.That implies that once the pension rights have been granted there is little motivation to continue employment ( Myck et al., 2009 ).

Key Public Policy Issues Related to Aging

Health and Long-Term Care

In contrast to the United States, Poland provides free healthcare to all of its citizens through the National Health Fund (NFZ), the publicly funded healthcare system. Currently, 98% of the population is covered by a health insurance provided by the government ( Sagan et al., 2011 ). All health policies and regulations are determined by the Ministry of Health. Health insurance contributions are collected by two social insurance institutions, namely the Social Insurance Institution and the Agricultural Social Insurance Fund, then pooled into the National Health Fund and distributed between its 16 regional branches. Due to limited financing, the NFZ limits the number of procedures health care professionals can perform. Consequently, the NFZ provides comprehensive but limited care, resulting in common complains about long wait times to access specialized services or lack of adequate coverage in some areas (e.g., dental services). Therefore, individuals who want to quickly gain access to specialist outpatient services or procedures that are not covered by the NFZ (e.g., cosmetic or laser vision correction surgery) use private healthcare. According to a study conducted by Strategia Market Research in 2013, 65% of Polish citizens and 91% of pregnant women use private healthcare. Although, out-of-pockets payments for the private healthcare are affordable, they may be a financial burden for those with chronic health conditions.

Within the health care system there are three types of residential long-term care facilities: care and treatment facilities, nursing and care facilities, and palliative care homes, coordinated by territorial governments. Chronic medical care homes (Zakład opiekuńczo-leczniczy, ZOL) provide nursing, rehabilitation, and pharmacological treatment for individuals who are dependent or disabled but do not need further hospitalization. Nursing homes (Zakład pielęgnacyjno-opiekuńczy, ZPO) were designed to provide care depending on the client’s health status. In addition, they offer the help of physiotherapists and psychologists. Palliative facilities (also called hospices) are designed to enhance the quality of life of patients who are faced with incurable disease. They provide nursing, pharmacological treatment, psychological, and religious services. Care and treatment facilities, nursing homes, and palliative facilities offer 24-hr care.

Eligibility is based on a standardized assessment which examines a person’s level of independence. There are also 175 private nonprofit care homes run by Caritas, a public benefit organization ( OECD, 2010 ). In addition to publically funded long-term facilities, older adults may choose to live in private LTC homes. The fee is negotiated by the organization and the client.

Another form of residential care exists in the public sector, mainly in the social assistance (welfare) system. There are two kinds of social assistance homes: residential (Dom Pomocy Społecznej, DPS) and adult day care homes (Dzienny Dom Pomocy Społecznej, DDPS; Golinowska, 2010 ). A residential social welfare home is an institution that provides around-the-clock accommodation. There are several kinds of residential homes, depending on the kind of care needed. For example, there are residential homes for the physically disabled, mentally ill, and chronically ill.

The adult day care homes provide assistance for families. Adult day care services are limited to 5 days per week and no more than 12hr per day. Older adults with cognitive impairment and mental disorders or patients with dementia are eligible to use adult day care homes. Care is provided free of charge and includes various therapeutic workshops and classes ( Sagan et al., 2011 ).

In 2008, less than 1% of the Polish population aged 65 and older received long-term care in an institution setting; in comparison, the OECD average is 4.2%. The proportion of elderly living in long-term facilities is still low mainly because individuals rely on families for informal care. It is estimated that more than 80% of LTC is provided by families, a phenomenon due to culturally strong family ties ( Golinowska, 2010 ). Unfortunately, financial assistance for family caregivers is very limited.

Retirement System

Older people in Poland are dependent mainly on pensions. There are several different pension systems in Poland that operate in parallel and are applicable depending on age (date of birth) and employment history.

Retirement reform introduced in 1999 is the basis for the current pension system in Poland. Prior to this reform, there was a defined benefit (DB) pay-as-you-go system. Since the reform in 1999, pensions in Poland have been based on a three pillar system. The first pillar is a defined contribution (DC; amounting to 19.52% of gross wages) pay-as-you-go (PAYG) scheme based on the Social Insurance Fund (Fundusz Ubezpieczeń Społecznych, FUS), managed by the Social Insurance Institution (Zakład Ubezpieczeń Społecznych, ZUS). The second one is based on the open pension fund (Otwarty Fundusz Emerytalny, OFE) run by private fund managers. Until 2014, the first two pillars had been mandatory but compulsory participation in the open pension fund has been abolished. This change is largely a result of the disclosure of pension debt, which, after the introduction of a DC scheme, began to be partially included in the official state debt. The Ministry of Finance wanted to reduce the public debt by abandoning mandatory participation in OFE. At the same time, it is estimated that this change will not have a significant impact on the level of future pensions, because the amount of pension contributions has not changed (19.52%), and the rate of return of Social Insurance Institution (ZUS) and open pension fund (OFE) are at similar levels.

Another problem is the deepening deficit in the Social Insurance Fund. The changes that have been introduced will not remedy it. Its main causes are demographic factors such as low birth rate, emigration, and increased life expectancy. Consequently, in the long run, without the support from the state budget, it may not be enough funds to pay pension benefits ( Rutecka, 2014 ).

The third pillar comprises voluntarily paid funds and includes, for example, Personal Voluntary Plans (Indywidualne Konta Emerytalne, IKEs), Individual Pension Insurance Accounts (Indywidualne Konta Zabezpieczenia Emerytalnego, IKZE), or Voluntary Occupational Pension plans (Pracownicze Programy Emerytalne, PPE). Currently, there is a small percentage of people participating in the third pillar.

Individuals born before January 1, 1949 constitute the majority of Polish elderly and are subject to the pension system that existed before the 1999 reform. Every person born on January 1, 1949 or after is required to join a mandatory personal pension plan. Contributions were adjusted to reflect how much the individual had saved under the so-called “old” pension system.

Moreover, from January 1, 2013, the retirement age in Poland has been increased by a month in January, May, and September each year until it reaches 67 for both sexes (women in 2040, men in 2020).

In Poland gross pension replacement rate shown as a share of gross pension in individual lifetime average gross earnings (revalued in line with economy-wide earnings growth) is 48.8% (Pensions at a Glance 2013: OECD and G20 Indicators). The minimum retirement guarantee is financed by state budget. More than 42% of retirees evaluate their current income as insufficient and 20% assess it as insufficient to meet basic needs ( Polish Central Statistical Office, 2012 ). In particular, healthcare costs of retirees exceed 179% of those of other households ( Ciura, 2012 ). According to OECD (2013) , old-age poverty in Poland has increased in the second half of the last decade. The overall poverty rate for the elderly increased from 7.7% in 2007 to 9.7% in 2010.

Emerging Issues on Aging

Aging of the population, emigration of young people, and declining birthrates create challenges that affect Poland’s economy, healthcare and retirement-income systems. Currently, the dependency ratio of those aged 65 and above to working population between 15 and 64 years is 20.1 aged individuals for every 100 workers, but it is anticipated that by 2050 the ratio will be about 52 aged individuals per 100 workers. European Commission researchers project that Poland’s potential growth in gross domestic product (GDP) per capita will decline from 4.7% of GDP to 3% of GDP after 2021, owing to the aging of the population ( Devictor, 2012 ). Such a significant change in GDP may have substantial effect on investments, unemployment rates, and individuals’ well-being by inducing fears of economic instability.

In light of the steady increase of the older population and declining fertility rates, concerns about the increasing strain on the health care and retirement systems brought about a national effort to focus on these issues. In 2012, the Polish government decided to introduce changes to the pension system in order to balance economic growth by postponing retirement. The retirement age will be increased to the age of 67 for both men and women, for women, not until 2040 but for and for men in 2020.

The Polish health care system will also be challenged by population aging. Recent estimates show that Poland spent 7.4% of its GDP on health which is over 2 percentage points less than the OECD average of 9.5% of GDP. Although current total expenditures for health care are not high, they are projected to increase due to increased need for long term care services. The health status of the Polish population has improved substantially since 1989, however; tobacco consumption and excessive weight gain remain two important risk factors for many chronic diseases. Cancer, especially lung cancer in men, remains the leading cause of death in Poland. While the percentage of adults who smoke every day has declined markedly in Poland from 41.5% in 1992 to 23.8% in 2013, it remains above the OECD average of 20.9%. At the same time, obesity among adults is increasingly prevalent in Poland (15.8%), slightly lower than the OECD average of 17.2%. Therefore, health promotion and prevention programs are urgently needed.

Another health concern is the growing burden of dementia. A report recently undertaken by Alzheimer Europe (2012) estimated that there are approximately 501092 Polish people diagnosed with dementia. That represents 1.31% of the total population and is slightly below the EU average of 1.55%. Most individuals with dementia live at home, cared for by family members. Because the number of individuals with dementia will increase in the years to come, reforms will be needed to ensure that older adults have access to high quality care and treatment appropriate for their needs.

As a response to demographic changes in August 2012 the Ministry of Labour and Social Policy established funds to support programs for promoting “active aging.” The Government Program for Senior Citizens Social Activity (ASOS, 2014–2020) was established with the goal of promoting well-being and extending the working life of older adults through engagement in social activities such as volunteering and learning opportunities. The main objectives of the program are based on four priorities: education of older adults; intergenerational social activities such as recreation activities for grandparents and grandchildren, participation of older adults in social activities such as gardening, interaction through learning, physical exercises with a group; and recruiting older adults as volunteers to do for example grocery shopping or cooking. With a total budget of 280 million PLN ($84 million), non-governmental organizations, sports clubs and associations of local governments are encouraged to keep older adults active and healthy. One of the great examples of engaging older people are Universities of the Third Age that aim to improve the lives of older adults through a range of educational activities such as learning basic English, social sciences, philosophy, or how to use a computer.

Conclusions

Similar to other countries, Poland is currently facing challenges of rapidly aging population. Increasing life expectancy and growing in size elderly population in Poland has begun to have a significant economic and social impact. In order to balance economic growth and provide an adequate care for older adults, public institutions, and nongovernmental organizations need to respond to those challenges.

First of all, there is an increased need for specialized health care workers, increased number of long-term care facilities, and prevention programs aiming at improvement of the health status of older adults.

Secondly, the gender imbalance at older ages, as demonstrated in Poland’s current age pyramid, results in significant implications for older women. Similar to Turkey, France, or Rumania, older women in Poland make up a greater proportion of the aging population. Many older women live without their spousal support what may negatively affect their economic status and lead to low psychological well-being. Therefore, it is important for Polish gerontologists to investigate the situation of older widows and to target interventions toward improving mental and physical health as well as to reduce the influence of financial burden on widows.

At the same time, the financial support for conducting gerontological and geriatric research in Poland needs to be increased so the research can contribute to public debate on aging and also allow researchers to translate the findings into practice. Although an increasing number of studies are being conducted at universities, there is a lack of longitudinal research on aging. Poland would benefit greatly if more resources were available to conduct research.

Poland has begun to respond to the aging-related challenges by introducing changes in health care and retirement systems. However, many individuals, particularly those with compromised health, are dissatisfied by the new retirement reform, especially the postponed retirement age.

References

Author notes

Decision Editor: Rachel Pruchno, PhD