Chronology of the ancient Near East

The chronology of the ancient Near East is a framework of dates for various events, rulers and dynasties. Historical inscriptions and texts customarily record events in terms of a succession of officials or rulers: "in the year X of king Y". Comparing many records pieces together a relative chronology relating dates in cities over a wide area.

For the 3rd and 2nd millennia BC, this correlation is less certain but the following periods can be distinguished: [1]

- Early Bronze Age: Following the rise of cuneiform writing in the preceding Uruk period and Jemdet Nasr periods came a series of rulers and dynasties whose existence is based mostly on scant contemporary sources (e.g. En-me-barage-si), combined with archaeological cultures, some of which are considered problematic (e.g. Early Dynastic II). The lack of dendrochronology, astronomical correlations, and sparsity of modern, well-stratified sequences of radiocarbon dates from Southern Mesopotamia makes it difficult to assign absolute dates to this floating chronology.[2][3]

- Middle Bronze Age: Beginning with the Akkadian Empire around 2300 BC, the chronological evidence becomes internally more consistent. A good picture can be drawn of who succeeded whom, and synchronisms between Mesopotamia, the Levant and the more robust chronology of Ancient Egypt can be established. Unlike the previous period there are a variety of data points serving to help turn this floating chronology into a fixed one. These include astronomical events, dendrochronology, radiocarbon dating, and even a volcanic eruption. Despite this no agreement has been reached. The most commonly seen solution is to place the reign of Hammurabi from 1792 to 1750 BC, the "middle chronology", but there is far from a consensus.[4][5]

- Late Bronze Age: The fall of the First Babylonian Empire was followed by a period of chaos where "Late Old Babylonian royal inscriptions are few and the year names become less evocative of political events, early Kassite evidence is even scarcer, and until recently Sealand I sources were near to non-existent".[6] Afterward came a period of stability with the Assyrian Middle Kingdom, Hittite New Kingdom, and the Third Babylon Dynasty (Kassite).

- The Bronze Age collapse: A "Dark Age" begins with the fall of Babylonian Dynasty III (Kassite) around 1200 BC, the invasions of the Sea Peoples and the collapse of the Hittite Empire.[7]

- Early Iron Age: Around 900 BC, written records once again become more numerous with the rise of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, establishing relatively secure absolute dates. Classical sources such as the Canon of Ptolemy, the works of Berossus, and the Hebrew Bible provide chronological support and synchronisms. An inscription from the tenth year of Assyrian king Ashur-Dan III refers to an eclipse of the sun, and astronomical calculations among the range of plausible years date the eclipse to 15 June 763 BC. This can be corroborated by other mentions of astronomical events, and a secure absolute chronology established, tying the relative chronologies to the now-dominant Gregorian calendar.

Variant Middle Bronze Age chronologies[edit]

Due to the sparsity of sources throughout the "Dark Age", the history of the Near Eastern Middle Bronze Age down to the end of the First Babylonian Dynasty is founded on a floating or relative chronology. There have been attempts to anchor the chronology using records of eclipses and other methods such as dendrochronology and radiocarbon dating, but none of those dates is widely supported.

Currently the major schools of thought on the absolute dating of this period are separated by 56 or 64 years. This is because the key source for this analysis are the omen observations in the Venus tablet of King Ammisaduqa and these are multiples of the eight-year cycle of Venus visibility from Earth. More recent work by Vahe Gurzadyan has suggested that the fundamental eight-year cycle of Venus is a better metric.[8][9][10] Some scholars discount the validity of the Venus tablet of Ammisaduqa entirely. The alternative major chronologies are defined by the date of the eighth year of the reign of Ammisaduqa, king of Babylon.

The most common Venus Tablet solutions (sack of Babylon)

- Long Chronology (sack of Babylon 1651 BC)[11]

- Middle Chronology (sack of Babylon 1595 BC)[12][13]

- Middle Low Chronology (sack of Babylon 1587 BC)[14][15][16][17]

- Short Chronology (sack of Babylon 1531 BC)[18][19]

- Ultra Short Chronology (sack of Babylon 1499 BC)[8]

The following table gives an overview of the different proposals, listing some key dates and their deviation relative to the middle chronology, omitting the Supershort Chronology (sack of Babylon in 1466 BC):

| Chronology | Ammisaduqa year 8 | Reign of Hammurabi | Sack of Babylon | ± |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ultra-Low | 1542 BC | 1696–1654 BC | 1499 BC | −96 a |

| Short or Low | 1574 BC | 1728–1686 BC | 1531 BC | −64 a |

| Middle Low | 1630 BC | 1784–1742 BC | 1587 BC | −8 a |

| Middle | 1638 BC | 1792–1750 BC | 1595 BC | +0 a |

| Long or High | 1694 BC | 1848–1806 BC | 1651 BC | +56 a |

Sources of chronological data[edit]

Astronomical[edit]

Venus tablet of Ammisaduqa[edit]

In the series, the conjunction of the rise of Venus with the new moon provides a point of reference, or rather three points, for the conjunction is a periodic occurrence. Identifying a conjunction during the reign of king Ammisaduqa with one of these calculated conjunctions will therefore fix, for example, the accession of Hammurabi as either 1848, 1792, or 1736 BC, known as the "high" ("long"), "middle", and "short (or low) chronology".

A record of the movements of Venus over roughly a 16-day period during the reign of a king, believed to be Ammisaduqa of the First Babylonian Dynasty, has been preserved on a tablet called Venus tablet of Ammisaduqa (Enuma Anu Enlil 63). Twenty copies and fragments have been recovered, all Neo-Assyrian and later. [20] An example entry is "In month XI, 15th day, Venus in the west disappeared, 3 days in the sky it stayed away, and in month XI, 18th day, Venus in the east became visible: springs will open, Adad his rain, Ea his floods will bring, king to king messages of reconciliation will send."[21] Using it, various scholars have proposed dates for the fall of Babylon based on the 56/64-year cycle of Venus. It has been suggested that the fundamental 8-year cycle of Venus is a better metric, leading to the proposal of an "ultra-low" chronology.[22] Other researchers have declared the data to be too noisy for any use in fixing the chronology.[23][24]

Eclipses[edit]

A number of lunar and solar eclipses have been suggested for use in dating the ancient Near East. Many suffer from the vagueness of the original tablets in showing that an actual eclipse occurred. At that point, it becomes a question of using computer models to show when a given eclipse would have been visible at a site, complicated by difficulties in modeling the slowing rotation of the earth (ΔT) and uncertainty about the lengths of months. [25][26] Most calculations for dating using eclipses have assumed the Venus Tablet of Ammisaduqa to be a legitimate source.[8][27] The most notable omitted eclipses are the Mari Eponym Chronicle eclipse from the time of Shamshi-Adad I and the Sargon of Akkad eclipse (from the Legends of the Kings of Akkad and a liver omen).[28][29]

Some important examples:

- Nineveh eclipse – a short text found in an Assyrian list of royal officials (limmū) which says the following: "Bur-Sagale of Guzana, revolt in the city of Ashur. In the month Simanu an eclipse of the sun took place." Bur-Sagale was the name of the royal official. The text was part of the Eponym dating system. This eclipse is considered to be solidly dated to 15 June 763 BC, corresponding to the ninth or eleventh year of the reign of king Ashur-dan III.[30]

- Mursili's eclipse – a text in the 10th year of the reign of Mursili II of the Hittite Empire, "[When] I marched [to the land of A]zzi, the Sungod gave a sign.", has been interpreted as an eclipse event. Proposed dates range between 1340 BC and 1308 BC.[31][32][33][34]

- Shulgi Eclipse – Based on a prophecy text called Enuma Anu Enlil 20 which states "If an eclipse occurs on the 14th day of Simānu ... The king of Ur, his son will wrong him, and the son who wronged his father, Šamaš will catch him. He will die in the mourning place of his father" from the end of the reign of Shulgi of the Ur III dynasty. A date of 25 July 2093 BC has been proposed. These prophecies were written after the fact to help predict future events. A second prophecy, EAE 21 (month 12), predicts the fall of Ur III in the reign of Ibbi-Sin stating "If an eclipse occurs on the 14th day of Addaru ... The prediction is given for the king of the world: The destruction of Ur".[35]

- Babylon Eclipse – Another section in EAE 20 (month 3) refers to the fall of Babylon i.e. "if an eclipse occurs on the 14th day of Shabattu (month XI), and the god, in his eclipse ... The prediction is given for Babylon: the destruction of Babylon is near ...". It refers to a solar eclipse followed by a lunar eclipse. The most likely solution, 1547 BC, does not match up with Venus Tablet solutions. There are textual problems with the prophecy and it has been suggested that Akkad is actually the city in question.[36]

- Tell Muhammad Eclipse - At Tell Muhammad several tablets, silver loan contracts, were found that were dated with two year names "Year 38 after Babylon was resettled" and "The year that the Moon was eclipsed". The former year name is of a format used by the Kassites, a change from the event format used through the Old Babylonian period. Attempts have been made to use this eclipse to date the sack of Babylon and its resettlement by the Kassites.[37][38][39]

Egyptian lunar observations[edit]

There are thirteen Egyptian New Kingdom lunar observations which are used to pin the chronology in that period by locking down the accession year of Ramsesses II to 1279 BC. There are a number of issues with this including a) the regnal lengths for Neferneferuaten, Seti I, and Horemheb are actually not known with accuracy, b) where the observations occurred (Memphis is usually assumed), c) what day the observations were taken (two are known to be the 1st lunar day), and d) the Egyptian calendar for this period is not fully known, especially how intercalary months were handled.[40] Since the Assyrian eponym list is accurate to one year only back to 1132 BC, ancient Near East chronology for the preceding century or so is anchored to Ramsesses II, based on synchronisms and the Egyptian lunar observations.[41] It has been suggested that lunar dates place the accession of Thutmose III, pharaoh of the Battle of Megiddo, to 1490 BC or even 1505 BC versus the current 1470 BC.[42]

Kudurru symbols[edit]

A number of attempts have been made to date Kassite Kudurru stone documents by mapping the symbols to astrononomical elements, using Babylonian star catalogues such as MUL.APIN with so far very limited results.[43][44]

Inscriptional[edit]

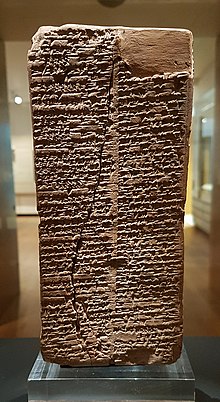

Thousands of cuneiform tablets have been found in an area running from Anatolia to Egypt. While many are the ancient equivalent of grocery receipts, these tablets, along with inscriptions on buildings and public monuments, provide the major source of chronological information for the ancient Middle East.[45]

Underlying issues[edit]

- State of materials

While there are some relatively pristine display-quality objects, the vast majority of recovered tablets and inscriptions are damaged. They have been broken with only portions found, intentionally defaced, and damaged by weather or soil. Many tablets were not even baked and have to be carefully handled until they can be hardened by heating.[46]

- Provenance

The site of an item's recovery is an important piece of information for archaeologists, which can be compromised by two factors. First, in ancient times old materials were often reused as building material or fill, sometimes at a great distance from the original location. Secondly, looting has disturbed archaeological sites at least back to Roman times, making the provenance of looted objects difficult or impossible to determine. Lastly, counterfeit versions of these object are a longstanding traditional, often difficult to detect.[47]

- Multiple versions

Key documents like the Sumerian King List were repeatedly copied and redacted over generations to suit current political needs. For this and other reasons, the Sumerian King List, once regarded as an important historical source, is now only used with caution, if at all, for the period under discussion here.[48]

- Translation

The translation of cuneiform documents is quite difficult, especially for damaged source material. Additionally, our knowledge of the underlying languages, like Akkadian and Sumerian, has evolved over time, so a translation done now may be quite different from one done in AD 1900: there can be honest disagreement over what a document says. Worse, the majority of archaeological finds have not yet been published, much less translated. Those held in private collections may never be.

- Political slant

Many of our important source documents, such as the Assyrian King List, are the products of government and religious establishments, with a natural bias in favor of the king or god in charge. A king may even take credit for a battle or construction project of an earlier ruler. The Assyrians in particular have a literary tradition of putting the best possible face on history, a fact the interpreter must constantly keep in mind.

King lists[edit]

Historical lists of rulers were traditional in the ancient Near East.

Covers rulers of Mesopotamia from a time "before the flood" to the fall of the Isin Dynasty, depending on the version. Its use for pre-Akkadian rulers is limited to none. It continues to have value for the Akkadian period and later.[48] The Sumerian King List omits any mention of Lagash, even though it was clearly a major power during the period covered by the list. The Royal Chronicle of Lagash appears to be an attempt to remedy that omission, listing the kings of Lagash in the form of a chronicle though some scholars believe the Lagash chronicle to be either a parody of the Sumerian King List or a complete fabrication.[49]

This list deals only with the rulers of Babylon. It has been found in two versions, denoted A and B both written in Neo-Babylonian times. The later dynasties in the list document the Kassite and Sealand periods though a number of Kassite rulers are damaged. Ruler names largely match other records but the regnal lengths are more problematic.[50] There is also a Babylonian King List of the Hellenistic Period in later part of the 1st millennium.[51]

The Assyrian King List extends back to the reign of Shamshi Adad I (1809 – c. 1776 BC), an Amorite who conquered Assur while creating a new kingdom in Upper Mesopotamia. The list extends to the reign of Shalmaneser V (727–722 BC). It is believed that the list was first constructed in the time of Ashur-uballit I (1365–1330 BC). The king list is considered to be roughly correct from that point on, less so for earlier entries which have numerous inconsistencies. Its purpose is to create a narrative of continuity and legitimacy for Assyrian kingship, blending in the kings of Amorite origin. [52] The existing source consists of 3 mostly complete tables and 2 small fragments. [53] [54] There are differences between the tablets involving regnal lengths, names, and in one case a king being left out entirely. Not surprising given that they are noted as being copies of earlier tablets. [55]

Chronicles[edit]

Many chronicles have been recovered in the ancient Near East, most fragmentary, with a political slant, and sometimes contradictory; but when combined with other sources, they provide a rich source of chronological data.[49]

Most available chronicles stem from later Babylonian and Assyrian sources. The Dynastic Chronicle, after a Sumerian King List type beginning, involves Babylonian kings from Simbar-Šipak (c. 1021–1004 BC) to Erība-Marduk (c. 769 – 761 BC). The Chronicle of Early Kings, after an early preamble, involves kings of the First Babylonian Empire ending with the First Sealand Dynasty. The Tummal Inscription relates events from the early Sumerian king Ishbi-Erra of Isin at the beginning of the second millennium BC. The Chronicle of the Market Prices mentions various Babylonian rulers beginning from the period of Hammurabi. The Eclectic Chronicle relates events of the post-Kassite Babylonian kings. Other examples are the Religious Chronicle, and Nebuchadnezzar Chronicle, among others.

The Synchronistic Chronicle, found in the library of Assurbanipal in Nineveh records the diplomacy of the Assyrian empire with the Babylonian empire. While useful, the consensus is that this chronicle should not be considered reliable. Chronicle P provides the same type of information as the Assyrian Synchronistic Chronicle, but from the Babylonian point of view.[56]

Royal inscriptions[edit]

Rulers in the ancient Near East liked to take credit for public works. Temples, buildings and statues are likely to identify their royal patron. Kings also publicly recorded major deeds such as battles won, titles acquired, and gods appeased. These are very useful in tracking the reign of a ruler.

Year lists[edit]

Unlike current calendars, most ancient calendars were based on the accession of the current ruler, as in "the 5th year in the reign of Hammurabi". Each royal year was also given a title reflecting a deed of the ruler, like "the year Ur was defeated". The compilation of these years are called date lists. [57][58][59]

Eponym (limmu) lists[edit]

In Assyria, a royal official or limmū was selected in every year of a king's reign. Many copies of these lists have been found,[60] with certain ambiguities. There are sometimes too many or few royal officials for the length of a king's reign, and sometimes the different versions of the eponym list disagree on a royal official, for example in the Mari Eponym Chronicle. The eponym list is considered accurate within 1 year back to 1133 BC. Before that uncertainty creeps in. There is now an Assyrian Revised Eponym List which attempts to resolve some of these issues.[61]

Trade, diplomatic, and disbursement records[edit]

As often in archaeology, everyday records give the best picture of a civilization. Cuneiform tablets were constantly moving around the ancient Near East, offering alliances (sometimes including daughters for marriage), threatening war, recording shipments of mundane supplies, or settling accounts receivable. Most were tossed away after use as one today would discard unwanted receipts, but fortunately for us, clay tablets are durable enough to survive even when used as material for wall filler in new construction.[62]

A key find was a number of cuneiform tablets from Amarna in Egypt, the city of the pharaoh Akhenaten. Mostly in Akkadian, the diplomatic language of the time, a number of them name foreign rulers including kings of Assyria and Babylon as well as Tushratta king of Mitanni and rulers of small states in the Levant. The letters date from the later stages of the reign of Amenhotep III (c. 1386–1349 BC) to the 2nd year of Tutankhamun (c. 1341–1323 BC). Assuming that the correct foreign rulers have been identified, this provides and important point of synchronization. Identification can be difficult due to the propensity for states to re-use regnal names. [63]

Classical[edit]

We have some data sources from the classical period:

Berossus, a Babylonian astronomer and historian born during the time of Alexander the Great wrote a history of Babylon which is a lost book. Portions were preserved by other classical writers, mainly Josephus via Alexander Polyhistor. The surviving material is in chronicle form and covers the Neo-Babylonian Empire period from Nabopolassar (627–605 BC) to Nabonidus (556–539 BC). [64]

- Canon of Ptolemy (Canon of Kings)

This book provides a list of kings starting with the Neo-Babylonian Empire and ending with the early Roman Emperors. The entries relevant to the ancient Near East run from Nabonassar (747–734 BC) to the Macedonian king Alexander IV (323–309 BC). Though mostly accepted as accurate there are known issues with the Canon. Some rulers are omitted, there are times for which no ruler is listed, and the early dates have been converted from the lunar calendar used by the Babylonians to the Egyptian solar calendar. [65] [56] [66]

Not having the stability of buried clay tablets, the records of the Hebrews have a great deal of ancient editorial work to sift through when used as a source for chronology. However, the Hebrew kingdoms lay at the crossroads of Babylon, Assyria, Egypt and the Hittites, making them spectators and often victims of actions in the area during the 1st millennium. Mostly concerned with regional events in the Levant, in 2 Kings 23 Hebrew: פַרְעֹה נְכֹה, romanized: Phare'oh Necho, thought to be pharaoh Necho II, is mentioned three times. Neo-Babylonian kings are mentioned in 2 Kings 20, Hebrew: בְּרֹאדַךְ בַּלְאֲדָן, romanized: Berodach Bal'adan, thought to be Marduk-apla-iddina II, in 2 Kings 24 Nebuchadnezzar II and in 2 Kings 25 Hebrew: אֱוִיל מְרֹדַךְ, romanized: Evil Merodach, thought to be Amel-Marduk. In Isaiah 38 the neo-Assyrian kings Sennacherib and Esarhaddon are mentioned.

Dendrochronology[edit]

Dendrochronology attempts to use the variable growth pattern of trees, expressed in their rings, to build up a chronological timeline. At present there are no continuous chronologies for the Near East, and a floating chronology has been developed using trees in Anatolia for the Bronze and Iron Ages. Professor of archaeology at Cornell, Sturt Manning, has spearheaded efforts to use this floating chronology with radiocarbon wiggle-match to anchor the chronology.[67][68] His research has recently been included in the Oxford History of the Ancient Near East and has been cited widely in the recent academic literature.[69]

Radiocarbon dating[edit]

As in Egypt and the eastern Mediterranean, radiocarbon dates run one or two centuries earlier than the dates proposed by archaeologists.[70] Recently, radiocarbon dates from the final destruction of Ebla have been shown to definitely favour the middle chronology (with the fall of Babylon and Aleppo at c. 1595 BC), and seem to discount the ultra-low chronology (same event at c. 1499 BC), although it is emphasized that this is not presented as a decisive argument.[71]

Radiocarbon dates in literature should be discounted if they do not include the raw C14 date and the calibration method. There have also been issues with dating for charcoal samples, which may reflect much older wood the charcoal was made from. There are also calibration issues with annual and regional C14 variations.[72] A further problem is that earlier archaeological dates used traditional radiocarbon dating while newer results sometimes come from Accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) radiocarbon dating which is more accurate. In recent years some properly calibrated radiocarbon dates have begun to appear:

- In 1991 Two grain samples from the Middle Uruk layer of the Uruk Mound at Abu Salabikh were accelerator radiocarbon dated with calibrated dates of 3520 ± 130 BC.[73] Calibration was based on that of Pearson.[74]

- In 2013 a bone awl from Kish from Phase 2 in the YWN area, the transition between Early Dynastic and Akkadian periods, was accelerator radiocarbon dated to 2471–2299 BC (3905 ± 27 C14 years BP).[3]

- In 2017 charcoal sample from the base area of the Umm Al Nar fortress tower at Tell Abraq provided a radiocarbon date of 2461–2199 BC (3840±40 C14 years BP). It was calibrated with IntCal13. The Umm Al Nar period is co-temporal with the Akkadian through Ur III periods in Mesopotamia.[75]

Other emerging technical dating methods include rehydroxylation dating, luminescence dating, archaeomagnetic dating and the dating of lime plaster from structures.[76][77][78][79][80]

Synchronisms[edit]

Egypt[edit]

At least as far back as the reign of Thutmose I, Egypt took a strong interest in the ancient Near East. At times they occupied portions of the region, a favor returned later by the Assyrians. Some key synchronisms:

- Battle of Kadesh, involving Ramses II of Egypt ("Year 5 III Shemu day 9") and Muwatalli II of the Hittite empire. This would be 12 May 1274 BC, in the usually accepted Egyptian chronology.[81] Recorded by both Egyptian (Kadesh inscriptions) and Hittite records.

- Peace treaty (Egyptian–Hittite peace treaty) between Ramses II of Egypt, in his 21st year of reign (roughly 1259 BC) and Hattusili III of the Hittites. Hieroglyphic copies were found at the temple of Amun at Karnak and at the Ramesseumand. Fragmentary Akkadian cuneiform fragments were found at Hattusa.[82]

- Amenhotep III (Amenophis III) marries the daughter of Shuttarna II of Mitanni. There is also a record of messages from the pharaoh to Kadashman-Enlil I of Babylon in the Amarna Letter (EA1–5). Other Amarna letters link Amenhotep III to Burnaburiash II of Babylon (EA6) and Tushratta of Mitanni (EA17–29) as well.

- Akhenaten (Amenhotep IV) married the daughter of Tushratta of Mitanni (as did his father Amenhotep III), leaving a number of records. He also corresponded with Burna-Buriash II of Babylon (EA7–11, 15), and Ashuruballit I of Assyria (EA15–16)

- Bay an official of the Egyptian queen Twosret, in a tablet (RS 86.2230) found at Ras Shamra, was in communication with Ammurapi, the last ruler of Ugarit. Bay was in office from approximately 1194–1190 BC. This sets an upper limit on the destruction date of Ugarit.[83][84]

- Pottery seals of the Egyptian pharaoh Pepi I have been found in the wreckage of the city of Ebla, destroyed by Naram-Sin of Akkad.[85]

There are problems with using Egyptian chronology. Besides some minor issues of regnal lengths and overlaps, there are three long periods of poorly documented chaos in the history of ancient Egypt, the First, Second, and Third Intermediate Periods, whose lengths are doubtful.[86] This means the Egyptian Chronology actually comprises three floating chronologies. The chronologies of Mesopotamia, the Levant and Anatolia depend significantly on the chronology of Ancient Egypt. To the extent that there are problems in the Egyptian chronology, these issues will be inherited in chronologies based on synchronisms with Ancient Egypt.[87][88][89]

Indus Valley[edit]

There is much evidence that the Bronze Age civilization of the Indus Valley traded with the Near East, including clay seals found at Ur III and in the Persian Gulf.[90] Seals and beads were also found at the site of Esnunna.[91][92] In addition, if the land of Meluhha does indeed refer to the Indus Valley, then there are extensive trade records ranging from the Akkadian Empire until the Babylonian Dynasty I.

Thera and Eastern Mediterranean[edit]

Goods from Greece made their way into the ancient Near East, directly in Anatolia and via the island of Cyprus in the rest of the region and Egypt. A Hittite king, Tudhaliya IV, even captured Cyprus as part of an attempt to enforce a blockade of the Assyrians.[93]

The eruption of the Thera volcano provides a possible time marker for the region. A large eruption, it would have sent a plume of ash directly over Anatolia and filled the sea in the area with floating pumice. This pumice appeared in Egypt, apparently via trade. Current excavations in the Levant may also add to the timeline. The exact date of the volcanic eruption has been the subject of strong debate, with dates, ranging between 1628 and 1520 BC. These dates are based on radiocarbon samples, dendrochronology, ice cores, and archaeological remains. Archaeological remains date the eruption toward the end of the Late Minoan IA period (c. 1636–1527 BC) roughly comparable to the beginning of the New Kingdom in Egypt.[94] Radiocarbon dating has placed it at between 1627 BC and 1600 BC with a 95% degree of probability.[95][96][97] Archaeologist Kevin Walsh, accepting the radiocarbon dating, suggests a possible date of 1628 and believes this to be the most debated event in Mediterranean archaeology.[98] For the ANE chronology a key problem is the lack of a linkage between the eruption and some point on the floating chronology of the Middle Bronze Age in the ANE.

See also[edit]

- Egyptian chronology

- Minoan chronology

- List of Mesopotamian dynasties

- List of rulers of Elam

- List of Neo-Hittite kings

- List of kings of Ebla

- List of kings of Mari

Notes[edit]

- ^ [1] Stuart W. Manning et al., Beyond megadrought and collapse in the Northern Levant: The chronology of Tell Tayinat and two historical inflection episodes, around 4.2ka BP, and following 3.2ka BP, PLOS ONE, October 29, 2020

- ^ Wencel, Maciej Mateusz (2017). "Radiocarbon Dating of Early Dynastic Mesopotamia: Results, Limitations, and Prospects". Radiocarbon. 59 (2): 635–645. Bibcode:2017Radcb..59..635W. doi:10.1017/RDC.2016.60. ISSN 0033-8222. S2CID 133337438. Archived from the original on 29 October 2021. Retrieved 31 October 2021.

- ^ a b [2] Zaina, F., "A Radiocarbon date from Early Dynastic Kish and the Stratigraphy and Chronology of the YWN sounding at Tell Ingharra", Iraq, vol. 77(1), pp. 225–234, 2015

- ^ [3] V.G.Gurzadyan, "Astronomy and the Fall of Babylon", Sky & Telescope, vol. 100, no.1 (July), pp. 40–45, 2000

- ^ [4] Herrmann, Virginia R., et al., "New evidence for Middle Bronze Age chronology from the Syro-Anatolian frontier", Antiquity, pp. 1-20, 2023

- ^ [5] Boivin, O., "The First Dynasty of the Sealand in History and Tradition", Doctoral dissertation, University of Toronto Canada, 2016

- ^ [6] Manning, Sturt W., et al., "Severe multi-year drought coincident with Hittite collapse around 1198–1196 bc.", Nature 614.7949, pp. 719-724, 2023

- ^ a b c [7] Gurzadyan, V. G., "On the Astronomical Records and Babylonian Chronology", Akkadica, vol. 119–120, pp. 175–184, 2000

- ^ Warburton, David A. (2011). "The fall of Babylon in 1499: another update". Akkadica. 132/1: 1–22.

- ^ Warburton, David A. (2013). "A Rejoinder in favour of an Ultra-Low Chronology". Akkadica. 134/1: 17–28.

- ^ Huber, Peter J., "Reviewed Work(s): Dating the Fall of Babylon. A reappraisal of second-millennium chronology by H. Gasche, J. A. Armstrong, S. W. Cole and V. G. Gurzadyan", Archiv Für Orientforschung, vol. 46/47, pp. 287–90, 1999

- ^ Brinkman, J. A., "Mesopotamian Chronology of the Historical Period", in A. L. Oppenheim, Ancient Mesopotamia. 2nd revised (by E. Reiner) ed. Chicago: University Press of Chicago, pp. 335–48, 1977

- ^ Höflmayer, Felix, and Sturt W. Manning, "A synchronized early Middle Bronze Age chronology for Egypt, the Levant, and Mesopotamia", Journal of Near Eastern Studies 81.1, pp. 1–24, 2022

- ^ Manning, Sturt W.; Griggs, Carol B.; Lorentzen, Brita; Barjamovic, Gojko; Ramsey, Christopher Bronk; Kromer, Bernd; Wild, Eva Maria (13 July 2016). "Integrated Tree-Ring-Radiocarbon High-Resolution Timeframe to Resolve Earlier Second Millennium BCE Mesopotamian Chronology". PLOS ONE. 11 (7): e0157144. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1157144M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0157144. PMC 4943651. PMID 27409585.

- ^ Manning, Sturt; Barjamovic, Gojko; Lorentzen, Brita (1 March 2017). "The Course of 14C Dating Does Not Run Smooth: Tree-Rings, Radiocarbon, and Potential Impacts of a Calibration Curve Wiggle on Dating Mesopotamian Chronology". Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections. 13: 70–81. ISSN 1944-2815. Retrieved 1 November 2021.

- ^ Nahm, Werner, "The Case for the Lower Middle Chronology.", Altorientalische Forschungen vol. 40, no. 2, pp. 350–72, 2013

- ^ [8] Teije De Jong, "Further Astronomical Fine-Tuning of the Old Assyrian and Old Babylonian Chronologies", Jaarbericht van het Vooraziatisch-Egyptisch Genootschap "Ex Oriente Lux", vol. 46, pp. 127-143, 2017

- ^ Amanda H. Podany, "Hana and the Low Chronology", Journal of Near Eastern Studies, vol. 73, no. 1, pp. 49-71, April 2014

- ^ Manning, Sturt W.; Kromer, Bernd; Kuniholm, Peter Ian; Newton, Maryanne W. (21 December 2001). "Anatolian Tree Rings and a New Chronology for the East Mediterranean Bronze-Iron Ages". Science. 294 (5551): 2532–2535. Bibcode:2001Sci...294.2532M. doi:10.1126/science.1066112. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 11743159. S2CID 33497945.

- ^ [9] Erica Reiner and David Pingree, "BM 2/1. Babylonian Planetary Omens. Part I: The Venus Tablet", Udena, 1975 ISBN 0-89003-010-3

- ^ [10] T. de Jong andV. Foertmeyer, "A new look at the Venus observations of Ammisaduqa: traces of the Santorini eruption in the atmosphere of Babylon?", Jaarbericht van het Vooraziatisch-Egyptisch Genootschap "Ex Oriente Lux", vol. 42, pp. 141-158, 2010

- ^ [11] Gurzadyan, V. G., "The Venus Tablet and Refraction", Akkadica, vol. 124, pp. 13–17, 2003

- ^ [12]Gasche, H.; Armstrong, J.A.; Cole, S.W.; Gurzadyan, V.G. (1998). Dating the Fall of Babylon: A Reappraisal of Second-Millennium Chronology. University of Ghent and the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. ISBN 978-1885923103.

- ^ H. Gasche, et al., "A Correction to 'The Fall of Babylon. A Reappraisal of Second-Millennium Chronology'", Akkadica 108, pp. 1-4, 1998

- ^ [13] B. Banjevic, "Ancient eclipses and dating the fall of Babylon", Publications of the Astronomical Observatory of Belgrade, vol. 80, pp. 251–257, May 2006

- ^ [14] Peter J. Huber, "Third Millennium BC Chronology and Clock-Time Correction", Cuneiform Digital Library Preprints, no. 22, CDLI, 8 September 2021

- ^ Mitchell, Wayne A., "Ancient Astronomical Observations and Near Eastern Chronology", JACF, vol. 3, pp. 7-26, 1990

- ^ [15] C. Michel, "Nouvelles données pour la chronologie du IIe millénaire", Nouvelles Assyriologiques Brèves et Utilitaires (NABU), issue 1, note 20, pp. 17-18, 2002

- ^ Huber, Peter. "Dating of Akkad, Ur III, and Babylon I", Organization, Representation, and Symbols of Power in the Ancient Near East: Proceedings of the 54th Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale at Würzburg 20–25 Jul, edited by Gernot Wilhelm, University Park, US: Penn State University Press, pp. 715-734, 2022

- ^ Rawlinson, Henry Creswicke, "The Assyrian Canon Verified by the Record of a Solar Eclipse, B.C. 763", The Athenaeum: Journal of Literature, Science and the Fine Arts, nr. 2064, pp. 660–661, 18 May 1867

- ^ Theo P. J. Van Den Hout, The Purity of Kingship: An Edition of CTH 569 and Related Hittite Oracle Inquiries of Tutẖaliya, 1998

- ^ Gautschy, R., "Remarks Concerning the Alleged Solar Eclipse of Muršili II.", Altorientalische Forschungen, vol. 44, no. 1, pp. 23–29, 2017. doi:10.1515/aofo-2017-0004

- ^ Devecchi, E., Miller, J.L., "Hittite-Egyptian synchronisms and their consequences for ancient Near Eastern chronology", in J. Mynářová (ed), Egypt and the Near East – The Crossroads. Proceedings of an International Conference on the Relations of Egypt and the Near East in the Bronze Age, Prague, Charles University, pp. 139-176, 2011

- ^ Miller, J.L., "Political interactions between Kassite Babylonia and Assyria, Egypt and Ḫatti during the Amarna Age", in A. Bartelmus and Katja Sternitzke (eds), Karduniaš. Babylonia Under the Kassites, Berlin, de Gruyter, pp. 93-11, 2017

- ^ Peter J. Huber, "Astronomy and Ancient Chronology", Akkadica 119–120, pp. 159–176, 2000

- ^ Khalisi, Emil (2020), The Double Eclipse at the Downfall of Old Babylon, arXiv:2007.07141

- ^ Calderbank, Daniel, "Dispersed Communities of Practice During the First Dynasty of the Sealand: The Pottery from Tell Khaiber, Southern Iraq", Babylonia under the Sealand and Kassite Dynasties, edited by Susanne Paulus and Tim Clayden, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 58-87, 2020

- ^ [16] V.G.Gurzadyan, "Astronomy and the Fall of Babylon", Sky & Telescope, vol. 100, no.1 (July), pp. 40–45, 2000

- ^ Gasche, Hermann, and Michel Tanret, eds., "Changing Watercourses in Babylonia: Towards a Reconstruction of the Ancient Environment in Lower Mesopotamia", Volume 1. Mesopotamian History and Environment Series II Memoirs V. Ghent and Chicago: University of Ghent and the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, 1998

- ^ Gautschy, Rita. "A Reassessment of the Absolute Chronology of the Egyptian New Kingdom and its 'Brotherly' Countries" Ägypten Und Levante / Egypt and the Levant, vol. 24, pp. 141–58, 2014

- ^ Weidner E., "Die grosse Königsliste aus Assur", AfO 3, 1926

- ^ Casperson, Lee W., "The Lunar Dates of Thutmose III", Journal of Near Eastern Studies, vol. 45, no. 2, pp. 139–50, 1986

- ^ Tuman, V.S., "Astronomical Dating of the Kudurru IM 80908", Sumer, vol. 46, pp. 98-106, 1989-1990

- ^ Pizzimenti, "The Kudurrus And The Sky. Analysis And Interpretation Of The Dog-Scorpion-Lamp Astral Pattern As Represented In Kassite Kudurrus Reliefs", February 2016 doi:10.5281/zenodo.220910

- ^ Cuneiform Texts and the Writing of History, Marc van de Mieroop, Routledge, 1999, ISBN 0-415-19532-2

- ^ [17] Robert K. Englund, "The Year: "Nissen returns joyous from a distant island"", 2003:1, CDLI, ISSN 1540-8779

- ^ Michel, Cécile. "Cuneiform Fakes: A Long History from Antiquity to the Present Day". Fakes and Forgeries of Written Artefacts from Ancient Mesopotamia to Modern China, edited by Cécile Michel and Michael Friedrich, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 25-60, 2020

- ^ a b Marchesi, Gianni (2010). "The Sumerian King List and the Early History of Mesopotamia". M. G. Biga - M. Liverani (Eds.), ana turri gimilli: Studi dedicati al Padre Werner R. Mayer, S. J., da amici e allievi (Vicino Oriente - Quaderno 5; Roma): 231–248. Archived from the original on 29 October 2021. Retrieved 15 September 2021.

- ^ a b Jean-Jacques Glassner, Mesopotamian Chronicles (2004) ISBN 1-58983-090-3

- ^ van Koppen, Frans. "The Old to Middle Babylonian Transition: History and Chronology of the Mesopotamian Dark Age" Ägypten Und Levante / Egypt and the Levant, vol. 20, pp. 453–63, 2010

- ^ A. J. Sachs and D. J. Wiseman, "A Babylonian King List of the Hellenistic Period", Iraq, vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 202–212, Autumn 1954

- ^ [18] Valk, Jonathan, "The Origins of the Assyrian King List", Journal of Ancient Near Eastern History, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 1–17, 2019

- ^ Gelb, Ignace J., "Two Assyrian King Lists.", Journal of Near Eastern Studies, vol. 13, pp. 209–230 and pls. XIV–XVII, 1954

- ^ Nassouhi, Essad., "Grande liste des rois d'Assyrie. Archiv für Orientforschung", vol. 4, pp. 1–11 and pls. I–II, 1927

- ^ Pruzsinszky, Regine, "Mesopotamian Chronology of the 2nd Millennium B.C.: An Introduction to the Textual Evidence and Related Chronological Issues.", Vienna: Austrian Academy of Sciences Press, 2009

- ^ a b A. K. Grayson, "Assyrian and Babylonian Chronicles, Texts from Cuneiform Sources", vol. 5, Locust Valley, N.Y., 1975 (Eisenbrauns reprint ISBN 978-1575060491)

- ^ [19] Marcel Sigrist and Peter Damerow, "Mesopotamian Year Names: Neo-Sumerian and Old Babylonian Date Formulae", CDLI at UCLA

- ^ Baqir, Taha, "Date-formulae and date-lists from Harmal.", Sumer, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 34-86, January 1949

- ^ de Boer, Rients. "Studies on the Old Babylonian Kings of Isin and Their Dynasties with an Updated List of Isin Year Names" Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und Vorderasiatische Archäologie, vol. 111, no. 1, pp. 5-27, 2021

- ^ Alan Millard, "The Eponyms of the Assyrian Empire 910–612 B.C.", State Archives of Assyria Studies 11, Helsinki: Neo-Assyrian Text Corpus Project, 1994

- ^ Gojko Barjamovic, Thomas Hertel and Mogens T. Larsen, "Ups and Downs at Kanesh: Chronology, History and Society in the Old Assyrian Period", Leiden: Nederlands Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten, 2012

- ^ Trevor Bryce, "Letters of the Great Kings of the Ancient Near East", Routledge, 2003 ISBN 0-415-25857-X

- ^ Moran, William L. (1992). The Amarna Letters. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. xiv. ISBN 0-8018-4251-4.

- ^ [20] Archived 11 November 2021 at the Wayback Machine R.J. (Bert) van der Spek, "Berossus as a Babylonian chronicler and Greek historian", in: R.J. van der Spek et al. eds. Studies in Ancient Near Eastern World View and Society presented to Marten Stol on the occasion of his 65th birthday, 10 November 2005, and his retirement from the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, pp. 277–318, Bethesda MD: CDL Press, 2008

- ^ A. Brinkman, "A Political History of Post-Kassite Babylonia, 1158–722 BC", Analecta Orientalia, vol. 43, Rome, 1968

- ^ [21] Leo Depuydt, "More Valuable than All Gold": Ptolemy's Royal Canon and Babylonian Chronology, Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 47, pp. 97–117, 1995

- ^ [22] Sturt W. Manning et al., "Radiocarbon offsets and old world chronology as relevant to Mesopotamia, Egypt, Anatolia and Thera (Santorini)", Nature Scientific Reports, vol. 10, 17 August 2020 doi:10.1038/s41598-020-69287-2

- ^ Manning, Sturt W.; Griggs, Carol B.; Lorentzen, Brita; Barjamovic, Gojko; Ramsey, Christopher Bronk; Kromer, Bernd; Wild, Eva Maria (13 July 2016). "Integrated Tree-Ring-Radiocarbon High-Resolution Timeframe to Resolve Earlier Second Millennium BCE Mesopotamian Chronology". PLOS ONE. 11 (7): e0157144. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1157144M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0157144. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4943651. PMID 27409585.

- ^ Höflmayer, Felix (18 August 2022). "Establishing an Absolute Chronology of the Middle Bronze Age". The Oxford History of the Ancient Near East: Volume II. pp. 1–46. doi:10.1093/oso/9780190687571.003.0011. ISBN 978-0190687571. Archived from the original on 1 September 2022. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- ^ Höflmayer, Felix, "Radiocarbon Dating and Egyptian Chronology—From the “Curve of Knowns” to Bayesian Modeling", The Oxford Handbook of Topics in Archaeology (online edn, Oxford Academic, 2 Oct. 2014), doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199935413.013.64

- ^ Matthiae, P., "The Destruction of Old Syrian Ebla", in Matthiae, P., Pinnock, F., Nigro, L. and Peyronel, L. (eds.) From relative chronology to absolute chronology: The second millennium BC in Syria-Palestine, Contributi del Centro Linceo Interdisciplinare "Beniamino Segre" N. 117. Roma, pp. 5–32, 2007

- ^ Dee, Michael W., and Benjamin J. S. Pope, "Anchoring Historical Sequences Using a New Source of Astro-Chronological Tie-Points", Proceedings: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, vol. 472, no. 2192, pp. 1–11, 2016

- ^ Susan Pollock, Caroline Steele and Melody Pope, "Investigations on the Uruk Mound, Abu Salabikh, 1990", Iraq, vol. 53, pp. 59–68, 1991

- ^ Pearson, G. W. et al., "High precision 14C measurement of Irish oaks to show the natural 14C variation from a.d. 1840 to 5210 b.c.", Radiocarbon 28, pp. 911-34, 1986

- ^ Magee, Peter, et al., "Tell Abraq during the second and first millennia BC: Site layout, spatial organisation, and economy", Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy 28.2, pp. 209-237, 2017

- ^ Wilson, Moira A.; Carter, Margaret A.; Hall, Christopher; Hoff, William D.; Ince, Ceren; Wilson, Moira A.; Savage, Shaun D.; McKay, Bernard; Betts, Ian M. (8 August 2009). "Dating fired-clay ceramics using long-term power law rehydroxylation kinetics" (PDF). Proceedings of the Royal Society A. 465 (2108): 2407–2415. Bibcode:2009RSPSA.465.2407W. doi:10.1098/rspa.2009.0117. S2CID 59491943. Retrieved 1 April 2020.

- ^ YvesGallet et al., "Possible impact of the Earth's magnetic field on the history of ancient civilizations", Earth and Planetary Science Letters, vol. 246, iss. 1–2, pp. 17-26, 15 June 2006

- ^ Jason A. Rech, "New Uses for Old Laboratory techniques", Near Eastern Archaeology, 67, 4, pp. 212–219, Dec. 2004

- ^ Jesper Olsen, "Revisiting radiocarbon dating of lime mortar and lime plaster from Jerash in Jordan: Sample preparation by stepwise injection of diluted phosphoric acid", Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, vol. 41, February 2022

- ^ [23] Vaknin, Yoav, et al. "Reconstructing biblical military campaigns using geomagnetic field data", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 119.44, 2022

- ^ [24] James Henry Breasted, "Ancient Records of Egypt: Historical Documents from the Earliest Times to the Persian Conquest", Ancient Records, Second Series, vol. 3, University of Chicago Press, 1906

- ^ Sürenhagen, Dietrich, "Forerunners of the Hattusili-Ramesses treaty", British Museum Studies in Ancient Egypt and Sudan (BMSAES), vol. 6, pp. 59–67, 2006

- ^ [25] Freu J, "La tablette RS 86.2230 et la phase finale du Royaume d’Ugarit.", Syria, vol. 65, pp.395–398, 1988

- ^ [26] Kaniewski D, Van Campo E, Van Lerberghe K, Boiy T, Vansteenhuyse K, et al., "The Sea Peoples, from Cuneiform Tablets to Carbon Dating", PLoS ONE, 6(6): e20232, 2011 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0020232

- ^ Alfonso Archi, Maria Giovanna Biga, "A Victory over Mari and the Fall of Ebla", Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 55, pp. 1–44, 2003

- ^ Thijs, Ad., "The Burial of Psusennes I and “The Bad Times” of P. Brooklyn 16.205", Zeitschrift für Ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde, vol. 141, no. 2, pp. 209-223, 2014

- ^ [27] Felix Höflmayer, "Tel Nami, Cyprus, and Egypt: Radiocarbon Dates and Early Middle Bronze Age Chronology", Palestine Exploration Quarterly, 2021 doi:10.1080/00310328.2020.1866329

- ^ Belmonte, Juan Antonio, and José Lull, "Astronomy and Chronology", Astronomy of Ancient Egypt: A Cultural Perspective", Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 467-529, 2023

- ^ Ward, William A., "The Present Status of Egyptian Chronology", Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, no. 288, pp. 53–66, 1992

- ^ Gadd, C. J., "Seals of Ancient Indian Style Found at Ur". Proceedings of the British Academy 18, pp. 191–210, 1932

- ^ Henri Frankfort, "The Indus civilization and the Near East", Annual Bibliography of Indian Archaeology for 1932, Leyden, VI, pp. 1-12, 1934

- ^ [28] Archived 16 November 2021 at the Wayback Machine J. MarkKenoyer et al., "A new approach to tracking connections between the Indus Valley and Mesopotamia: initial results of strontium isotope analyses from Harappa and Ur", Journal of Archaeological Science, vol. 40, iss. 5, pp. 2286-2297 May 2013

- ^ Urbanism on Late Bronze Age Cyprus: LC II in Retrospect, Ora Negbi, Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, iss. 337, pp. 1–45, Feb 2005

- ^ Mühlenbruch, Tobias, "The absolute dating of the volcanic eruption of Santorini/Thera (periferia South Aegean/GR) – an alternative perspective", Praehistorische Zeitschrift, vol. 92, no. 1-2, pp. 92-107, 2017

- ^ Friedrich, Walter L; Kromer, B; Friedrich, M; Heinemeier, J; Pfeiffer, T; Talamo, S (2006). "Santorini Eruption Radiocarbon Dated to 1627–1600 B.C." Science. 312 (5773). American Association for the Advancement of Science: 548. doi:10.1126/science.1125087. PMID 16645088. S2CID 35908442. Archived from the original on 19 June 2010. Retrieved 10 March 2007.

- ^ Manning, Sturt W., et al., "Chronology for the Aegean Late Bronze Age 1700-1400 B.C.", Science, vol. 312, no. 5773, pp. 565–569, 2006

- ^ Manning, SW (2003). "Clarifying the "high" v. "low" Aegean/Cypriot chronology for the mid second millennium BC: assessing the evidence, interpretive frameworks, and current state of the debate" (PDF). In Bietak, M; Czerny, E (eds.). The Synchronisation of Civilisations in the Eastern Mediterranean in the Second Millennium B.C. III. Proceedings of the SCIEM 2000 – 2nd EuroConference, Vienna 28th of May – 1st of June 2003. Vienna, Austria. pp. 101–137. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Walsh, Kevin (2013). The Archaeology of Mediterranean Landscapes: Human-Environment Interaction from the Neolithic to the Roman Period. Cambridge University Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0521853019.

Further reading[edit]

- Bietak, M., "Problems of Middle Bronze Age Chronology: New Evidence from Egypt", AJA 88, pp. 471–485, 1984

- Bietak, M., "The Middle Bronze Age of the Levant — A New Approach to Relative and Absolute Chronology", in Åström, P. ed. High, Middle or Low, Part 3, Gothenburg, pp. 78–120, 1989

- [29] Johannes van der Plicht1 and Hendrik J Bruins, "Radiocarbon Dating in Near-Eastern Contexts: Confusion and Quality Control", Radiocarbon, vol. 43, no. 3, pp. 1155–1166, January 2006

- [30] Gerard Gertoux, "Mesopotamian chronology over the period 2340-539 BCE through astronomically dated synchronisms and comparison with carbon-14 dating", ASOR 2019 Annual Meeting, Richard Coffman, Nov 2019, San Diego CA, United States, 2023

- Grigoriev, Stanislav, "Chronology of the Seima-Turbino bronzes, early Shang Dynasty and Santorini eruption", Praehistorische Zeitschrift, vol. 98, no. 2, pp. 569–588, 2023

- [31] Neocleous, A., Azzopardi, G., & Dee, M. W., "Identification of possible δ14C anomalies since 14 ka BP: A computational intelligence approach", Science of the Total Environment, vol. 663, pp. 162–169, 2019 doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.01.251

- Albrecht Goetze, "The Kassites and Near Eastern Chronology," Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 18, no. 4, pp. 97–101, 1964

- Manning, Sturt W., et al., "Dating the Thera (Santorini) eruption: archaeological and scientific evidence supporting a high chronology". Antiquity 88.342, pp. 1164–1179, 2014

- Miller, Jared L., "Amarna Age Chronology and the Identity of Nibḫururiya in the Light of a Newly Reconstructed Hittite Text1", Altorientalische Forschungen, vol. 34, no. 2, pp. 252–293, 2007

- Otto, Adelheid, "From Pottery to Chronology: The Middle Euphrates Region in Late Bronze Age Syria", Proceedings of the International Workshop in Mainz (Germany), May 5–7, 2012, Gladbeck: PeWe-Verlag 2018

- Ramsey, Christopher Bronk, et al., "Radiocarbon-Based Chronology for Dynastic Egypt", Science, vol. 328, no. 5985, pp. 1554–57, 2010

- [32] Walther Sallaberger and Ingo Schrakam, "Associated Regional Chronologies for the Ancient Near East and the Eastern Mediterranean: History and Philology (Arcane)", Brepols Publishers (4 March 2015) ISBN 978-2503534947

- Glenn Schwartz, "Problems of Chronology: Mesopotamia, Anatolia, and the Syro-Levantine Region", in Beyond Babylon: Art, Trade, and Diplomacy in the Second Millennium B.C., Metropolitan Museum of Art, pp. 450–452, 2008 ISBN 978-0300141436

- [33] Webster, Lyndelle C., et al., "Towards a Radiocarbon-Based Chronology of Urban Northern Mesopotamia in the Early to Mid-Second Millennium BC: Initial Results from Kurd Qaburstan", Radiocarbon, pp. 1–16, 2023

- H. Weiss et al., "The Genesis and Collapse of Third Millennium North Mesopotamian Civilization", Science, vol. 261, iss. 5124, pp. 995–1004, 20 August 1993