Yolande Du Bois

Last updatedThis article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page . (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

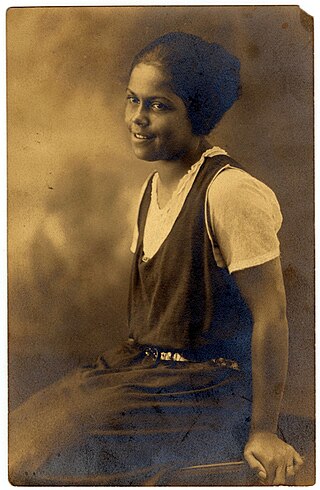

Yolande Du Bois | |

|---|---|

Yolande Du Bois Cullen in her weddine ensemble, from a 1928 publication | |

| Born | October 21, 1900 |

| Died | March 1961 |

| Occupation | Educator |

| Spouse | Countee Cullen |

| Parent | W.E.B. Du Bois |

Nina Yolande Du Bois (October 21, 1900 – March 1961), known as Yolande Du Bois, was an American teacher known for her involvement in the Harlem Renaissance. She was the daughter of W.E.B. Du Bois and the former Nina Gomer. Her father encouraged her marriage to Countee Cullen, a nationally known poet of the Harlem Renaissance. They divorced within two years. She married again and had a daughter, Du Bois's only grandchild. That marriage also ended in divorce. [1] [2]

Contents

Du Bois graduated from Fisk University and later earned an MA from Columbia University. She worked as a teacher, primarily in Baltimore, Maryland.

Early life

Du Bois was born on October 21, 1900, in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, [3] her father's hometown, to W.E.B. and Nina (née Gomer) Du Bois. [4] They had arrived there from Atlanta, Georgia, shortly after the death of their infant son Burghardt from diphtheria in 1899. [3] When Yolande was growing up, she did not have a close relationship with her father. He was often away for his career, or living in a different city altogether for academic research and assignments. [5] Yolande was often ill. A family physician diagnosed the girl as having "inadequate levels of lime" when she had poor health. Some biographers thought that Yolande faked these illnesses to gain her father's attention. [5] As a child, Yolande was defiant toward her parents. She was aggressive and passionate in nature. Her father described their relationship as one in which she held the power. To gain some control, her parents sent her to Bedales, a British boarding school. [6] While dealing with racial discrimination, she graduated from Brooklyn's Girls' High School. [5]

Du Bois began attending Fisk University in 1920. In her sophomore year she fell ill, and spent the entire month of February in the hospital due to serious inflammation of the gums. [5] While in college, Yolande was in a loving romance with jazz musician Jimmie Lunceford. However, her father believed he was an unsuitable match. Defying her parents' wishes, she continued to see Lunceford for some time. The relationship ended when she conceded to her father's wish that she marry poet Countee Cullen, who had received early acclaim in his career. [6]

She graduated from Fisk and started teaching in Baltimore, Maryland at a public high school.

Marriage and family

This section needs additional citations for verification .(April 2018) |

Du Bois first met Countee Cullen in 1923, when they were both students in college, she at Fisk and he at New York University (NYU). [7] She married him on April 9, 1928, at Salem Methodist Episcopal Church in Harlem, in a wedding officiated by his adoptive father, Frederick A. Cullen, a minister. Countee’s close friend, Harold Jackman, had introduced the pair to each other, likely at the Jersey Shore where Countee's parents had a house in Pleasantville. With the approval of Yolande's father, Countee proposed during the holiday season of 1927.

He and Du Bois spent the next couple of months planning the wedding with little contribution from Yolande. The April 9th wedding became the social event of the year, a highlight among the black elite. The public African-American press published every detail of the wedding, including the rail car used and the number of people in the wedding party. Du Bois pressured Countee to pick up the marriage certificate early to prevent any problems or delays; he acquired it four days before the ceremony. Some 1,200 people from Du Bois' wide political and activist circle were invited to the wedding, but 3,000 people crowded into the church for the ceremony. Yolande had 16 bridesmaids and Cullen had 9 groomsmen. Jackman served as the best man. [8] [9]

After the wedding Yolande and Countee visited Philadelphia, Atlantic City, New Jersey, and Great Barrington, Massachusetts in a brief honeymoon. During the honeymoon, Yolande wrote to her father, saying that she was unsure about her marriage and her intimate relationship with her husband. Her father responded that she simply needed more experience. [9] In June 1928 Countee, his father and Jackman traveled together to Paris, as Countee had received a Guggenheim Fellowship for study in Europe. Yolande joined him in August. By September 1928, her father was counseling Cullen on maintaining the marriage. After Cullen admitted to Yolande that he was attracted to men, she filed for divorce. Like the wedding, the divorce was negotiated between Cullen and Yolande's father; it became final in Paris in the spring of 1930. (Countee married again in 1940 and stayed married until his death several years later.)

Later adulthood

Yolande fell ill and moved back to Baltimore. She entered the American Hospital, where she was treated for an undisclosed illness. [10] After she was well, she returned to her teaching position. She took a job at Dunbar High School, teaching both English and history. [6]

While teaching, she met Arnette Franklin Williams, who had begun attending a night school held at Dunbar. Du Bois and Williams married in September 1931. Their daughter Du Bois Williams was born October 11, 1932. The family informally called her "Baby Du Bois." Soon after her birth, Williams moved to Pennsylvania for his football career and abandoned Yolande and his daughter. [11]

Du Bois and her mother moved to New York City, where she began taking classes at Columbia University’s Teachers College. [12] She earned a master's degree from Columbia and returned to teaching in Baltimore. Her divorce from Williams was final in 1936. [6]

Career as teacher and later life

Yolande Du Bois Williams returned to Baltimore, where she worked as a teacher and reared her daughter. Her mother died in 1950. Her father remarried about a year later.

Yolande's daughter, Du Bois Williams, married Arthur Edward McFarlane, Sr., and had a son, the first male born in the Du Bois family since Burghardt in 1897 (that child had died tragically at 18 months of age and was the topic of a chapter in W.E.B. Du Bois' most famous book, The Souls of Black Folk). Arthur Edward McFarlane, II, was born December 25, 1957, to W.E.B. Du Bois' great delight. At Du Bois' 90th birthday party in New York City, his speech was addressed to his great-grandson, Arthur. Yolande, her daughter, Du Bois, her husband, and their son all attended.

Yolande Du Bois Williams died in Baltimore of a heart attack in March 1961. [3] Yolande was buried in the Mahaiwe Cemetery at Great Barrington, Massachusetts, her father's hometown, beside her mother, Nina Du Bois, and brother Burghardt, who had died as an infant. [10] Williams' grandson, Arthur E. McFarlane II, arranged to install a headstone at her grave in Great Barrington in 2014. That year was also the occasion of dedication of a new interpretive trail at the W.E.B. Du Bois Boyhood Homesite, a National Historic Landmark in the city. [3]

After Yolande's death, her father accepted an invitation from Kwame Nkrumah to go to Ghana, where he worked on his proposed Encyclopedia Africana. He was unable to complete it before his death there in 1963. He was buried in Ghana. His second wife, the writer and activist Shirley Graham Du Bois, was also buried there, years later.

Yolande Du Bois Williams, W. E. B. Du Bois' only granddaughter, married and became known as Yolande Du Bois Irvin. She attended Fisk University and then New York University to get her bachelor's degree, and earned a Ph.D. in psychology at the University of Colorado. She joined the psychology faculty of Xavier University of Louisiana in 1988 and taught there until her retirement. She died on November 15, 2021, at age 89 and was buried in Great Barrington alongside her mother and other Du Bois family members. [11]

Related Research Articles

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois was an American sociologist, socialist, historian, and Pan-Africanist civil rights activist.

Nellallitea "Nella" Larsen was an American novelist. Working as a nurse and a librarian, she published two novels, Quicksand (1928) and Passing (1929), and a few short stories. Though her literary output was scant, she earned recognition by her contemporaries.

Countee Cullen was an American poet, novelist, children's writer, and playwright, particularly well known during the Harlem Renaissance.

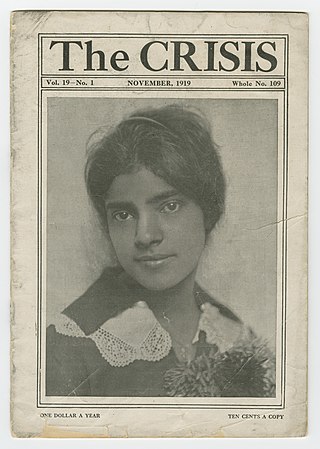

The Crisis is the official magazine of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). It was founded in 1910 by W. E. B. Du Bois (editor), Oswald Garrison Villard, J. Max Barber, Charles Edward Russell, Kelly Miller, William Stanley Braithwaite, and Mary Dunlop Maclean. The Crisis has been in continuous print since 1910, and it is the oldest Black-oriented magazine in the world. Today, The Crisis is "a quarterly journal of civil rights, history, politics and culture and seeks to educate and challenge its readers about issues that continue to plague African Americans and other communities of color."

James Augustus Van Der Zee was an American photographer best known for his portraits of black New Yorkers. He was a leading figure in the Harlem Renaissance. Aside from the artistic merits of his work, Van Der Zee produced the most comprehensive documentation of the period. Among his most famous subjects during this time were Marcus Garvey, Bill "Bojangles" Robinson and Countee Cullen.

Nigger Heaven is a novel written by Carl Van Vechten, and published in October 1926. The book is set during the Harlem Renaissance in the United States in the 1920s. The book and its title have been controversial since its publication.

Niggerati was the name used, with deliberate irony, by Wallace Thurman for the group of young African-American artists and intellectuals of the Harlem Renaissance. "Niggerati" is a portmanteau of "nigger" and "literati". The rooming house where he lived, and where that group often met, was similarly christened Niggerati Manor. The group included Zora Neale Hurston, Langston Hughes, and several of the people behind Thurman's journal FIRE!!, such as Richard Bruce Nugent, Jonathan Davis, Gwendolyn Bennett, and Aaron Douglas.

Gwendolyn B. Bennett was an American artist, writer, and journalist who contributed to Opportunity: A Journal of Negro Life, which chronicled cultural advancements during the Harlem Renaissance. Though often overlooked, she herself made considerable accomplishments in art, poetry, and prose. She is perhaps best known for her short story "Wedding Day", which was published in the magazine Fire!! and explores how gender, race, and class dynamics shape an interracial relationship. Bennett was a dedicated and self-preserving woman, respectfully known for being a strong influencer of African-American women rights during the Harlem Renaissance. Throughout her dedication and perseverance, Bennett raised the bar when it came to women's literature and education. One of her contributions to the Harlem Renaissance was her literary acclaimed short novel Poets Evening; it helped the understanding within the African-American communities, resulting in many African Americans coming to terms with identifying and accepting themselves.

Dorothy West was an American novelist short-story writer, and magazine editor associated with the Harlem Renaissance. She was one of the few Black women writers to be published in major literary magazines in the 1930s and 1940s. She is best known for her 1948 novel The Living Is Easy, as well as other short stories and essays, about the life of an upper-class black family.

Regina M. Anderson was an American playwright and librarian. She was of Native American, Jewish, East Indian, Swedish, and other European ancestry ; one of her grandparents was of African descent, born in Madagascar. Despite her own identification of her race as "American," she was perceived to be African-American by others. Influenced by Ida B. Wells and the lack of Black history teachings in school, Anderson became a key member of the Harlem Renaissance.

Fire!! was an African-American literary magazine published in New York City in 1926 during the Harlem Renaissance. The publication was started by Wallace Thurman, Zora Neale Hurston, Aaron Douglas, John P. Davis, Richard Bruce Nugent, Gwendolyn Bennett, Lewis Grandison Alexander, Countee Cullen, and Langston Hughes. The magazine's title referred to burning up old ideas, and Fire!! challenged the norms of the older Black generation while featuring younger authors. The publishers promoted a realistic style, with vernacular language and controversial topics such as homosexuality and prostitution. Many readers were offended, and some Black leaders denounced the magazine. The endeavor was plagued by debt, and its quarters burned down, ending the magazine after just one issue.

The Harlem Renaissance was an intellectual and cultural revival of African American music, dance, art, fashion, literature, theater, politics and scholarship centered in Harlem, Manhattan, New York City, spanning the 1920s and 1930s. At the time, it was known as the "New Negro Movement", named after The New Negro, a 1925 anthology edited by Alain Locke. The movement also included the new African American cultural expressions across the urban areas in the Northeast and Midwest United States affected by a renewed militancy in the general struggle for civil rights, combined with the Great Migration of African American workers fleeing the racist conditions of the Jim Crow Deep South, as Harlem was the final destination of the largest number of those who migrated north.

The W.E.B. Du Bois Boyhood Homesite is a National Historic Landmark in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, commemorating an important location in the life of African American intellectual and civil rights activist W.E.B. Du Bois (1868–1963). The site contains foundational remnants of the home of Du Bois' grandfather, where Du Bois lived for the first five years of his life. Du Bois was given the house in 1928, and planned to renovate it, but was unable to do so. He sold it in 1954 and the house was torn down later that decade.

Clarissa Scott Delany, neeClarissa Mae Scott (1901–1927) was an African-American poet, essayist, educator and social worker associated with the Harlem Renaissance.

Ariel Williams Holloway was an African-American poet of the Harlem Renaissance.