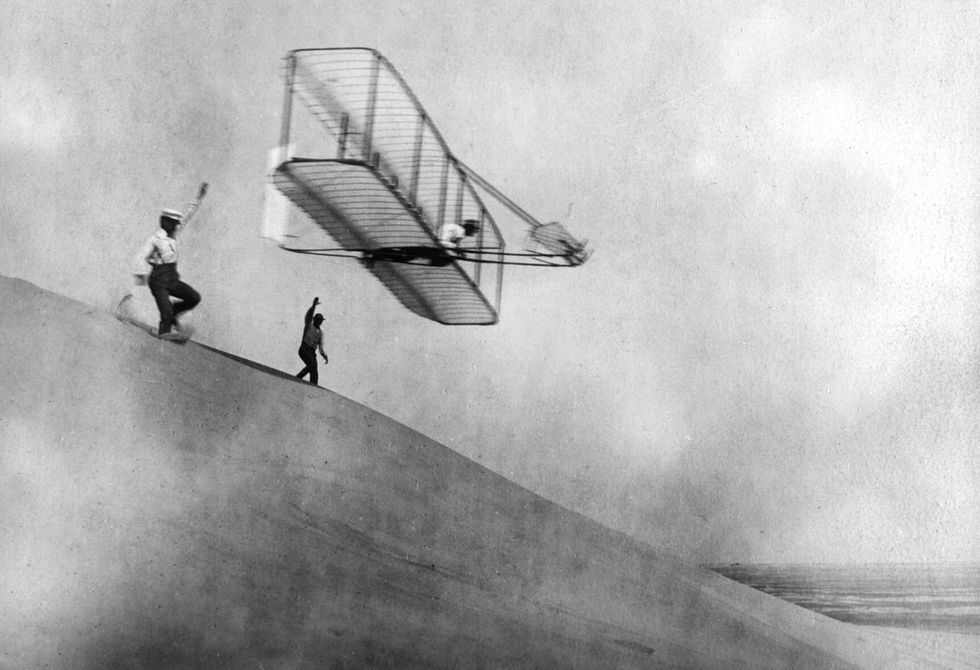

It was 12 seconds that would change the world forever. On the cold, windy morning of December 17, 1903, on the sandy dunes of Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, a small handful of men gathered around a homemade mechanical contraption of wood and fabric. They were there to witness the culmination of years of study, trial and error, sweat and sacrifice made by two humble, modest men from Dayton, Ohio. That day, the Wright Brothers’ dreams of flight would come to fruition, as Orville Wright took to the sky for 12 bumpy seconds.

“I like to think about that first airplane, the way it sailed off in the air as pretty as any bird you ever laid your eyes on. I don’t think I ever saw a prettier sight in my life," eye-witness John T. Daniels later recalled.

Daniels was in awe of Orville and his older brother, Wilbur, who he called "the workingest boys" he ever met in his life. For these two thoughtful bachelor brothers, their years of low-key, methodical research had finally paid off. Always cautious, Orville was shocked at “our audacity in attempting flights in a new and untried machine under such circumstances.”

The Wright brothers first became interested in flying when their father bought them a 50 cent helicopter

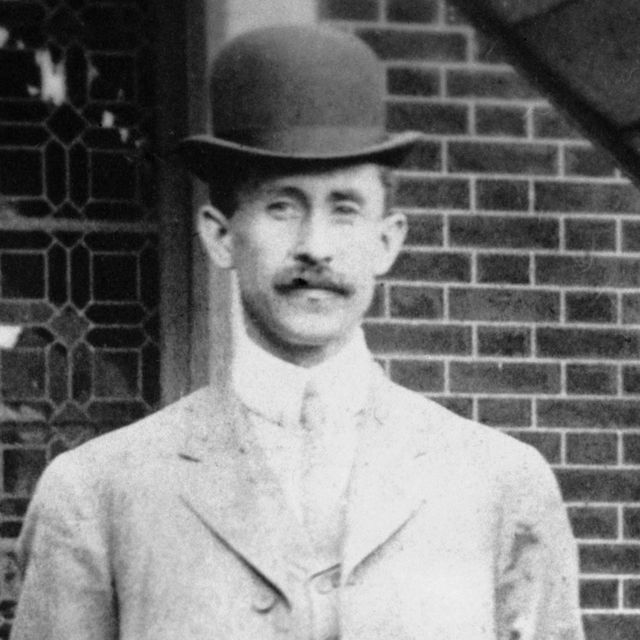

Wilbur was born in 1867, and Orville followed in 1871. According to biographer David McCullough, the boys’ loving father, Milton, was a bishop in the liberal United Brethren Church in Christ. Their mother, Susan, was shy and inventive, able to make anything – especially custom toys for her children.

Although there would be five children in the family, from the start Wilbur and Orville would share a special, almost symbiotic bond. From an early age, the boys were wrapped in dreams of discovery. Their interest in aviation was sparked early by their father when he brought home a small 50 cent French toy that worked as a rudimentary helicopter.

“Orville’s first teacher in grade school, Ida Palmer, would remember him at his desk tinkering with bits of wood,” McCullough writes in The Wright Brothers. “Asked what he was up to, he told her he was making a machine of a kind that he and his brother were going to fly someday.”

As close as they were, the brothers were very opposite in personality

Unlike the rest of their siblings, including their beloved sister, Katharine, the brothers never attended college. In 1889, while still in high school, Orville started a printing press. Wilbur soon joined him in the venture, and in 1893 the boys opened a bicycle shop they would name the Wright Cycle Company in Dayton, Ohio. Cycling was all the rage, and the brothers were soon designing and fabricating their own bikes

Although they would work and live together until Wilbur’s early death, the brothers were not without their individual quirks. According to McCullough, Wilbur was more hyper, outgoing, serious and studious – he never forgot a fact and seemed to live in his own head. On the contrary, Orville was very shy, but also much happier, with a sunnier outlook on life. He also had a brilliant, mechanically oriented mind.

Orville and Wilbur lived with their father and Katharine, who taught school and took care of her eccentric brethren. "Katharine was their rock,” says Dawn Dewey of Wright State University in Dayton. “I've heard her referred to as the third Wright brother."

While Orville was recovering from typhoid fever, they rediscovered their childhood obsession with flight

1896 would prove to be a turning point for the entire Wright family. That year, Orville was struck with typhoid fever. Wilbur rarely left Orville’s side, and while nursing his younger brother, he began to read up on the tragic aviation pioneer Otto Lilienthal, who had died during one of his experiments. Soon Wilbur was rediscovering his childhood obsession with flight, and as Orville convalesced, he began to read up on gliders and flight theory as well. The brothers became avid bird watchers, studying how they flew.

“Learning the secret of flight from a bird was a good deal like learning the secret of magic from a magician,” Orville would later say.

The brothers began writing the Smithsonian Institute and the Weather Bureau for information and advice regarding theories of flight and aeronautics. Around the turn of the century, in the back of their booming bike shop, they began to construct their own glider.

They went to the beach town of Kitty Hawk, North Carolina to test their gliders

When the time came to test their new machine, they decided to travel to remote Kitty Hawk, a small beach community with large sand dunes on the fabled Outer Banks of North Carolina. Here, they befriended William Tate, the former postmaster of Kitty Hawk, and made friends with many locals who were bemused and confused by these stoic, self-reliant brothers. “We couldn’t help thinking they were just a pair of poor nuts,” John T. Daniels recalled. “They’d stand on the beach for hours at a time just looking at the gulls flying, soaring, dipping.”

Despite Kitty Hawkers’ initial skepticism, the brothers made many friends on the island and became frequent visitors, camping out and testing their gliders for months at a time. The Wrights set up camp and later built their own workshop there, where they were visited by family members, curious aviation enthusiasts and aeronautics pioneers like Octave Chanute.

Orville described the 12-second first flight as 'extremely erratic'

By 1903, the brothers were confident that they could build a Flyer that included an engine and solicited mechanic Charlie Taylor, who ran the bike shop for them in Dayton, to build the light-weight engine. Throughout the year, they built their new improved flying machine. In the fall, they decamped for Kitty Hawk once again, ready to make the first powered flight in the history of the world. When the plane and conditions were finally ready, the brothers took to the sand dunes, with five locals nervously holding their breath. According to McCullough:

At exactly 10:35, Orville slipped the rope restraining the Flyer and it headed forward, but not very fast, because of the fierce headwind, and Wilbur, his left hand on the wing, had no trouble keeping up. At the end of the track the Flyer lifted into the air and Daniels, who had never operated a camera until now, snapped the shutter to take what would be one of the most historic photographs of the century. The course of the flight, in Orville’s words, was “extremely erratic.” The Flyer rose, dipped down, rose again, bounced and dipped again like a bucking bronco when one wing struck the sand. The distance flown had been 120 feet, less than half the length of a football field. The total time airborne was approximately 12 seconds. “Were you scared?” Orville would be asked. “Scared?” he said with a smile. “There wasn’t time.”

Despite making history, the Wrights received very little praise

Amazingly, this historic feat barely registered in the local and national news. Only a few days before the brothers’ successful flight, the $70,000 flying machine built by Samuel P. Langley, secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, had crashed in the Potomac River. While Langley’s failure was a sensational, much-covered story, the press-shy brothers’ success was scoffed at, if acknowledged at all.

Back in Dayton, the Wrights continued experimenting with their powered Flyer at Huffman Prairie, 84 secluded acres outside of their hometown. With little fanfare, the brothers became expert flyers, while the media still doubted and ignored their every move. “If they will not take our word and the word of many witnesses . . . we do not think they will be convinced until they see a flight with their own eyes,” Wilbur wrote.

Instead, the brothers concentrated on the joys of manned flight. “When you know, after the first few minutes, that the whole mechanism is working perfectly, the sensation is so keenly delightful as to be almost beyond description," Wilbur said. "Nobody who has not experienced it for himself can realize it. It is a realization of a dream so many persons have had of floating in the air. More than anything else the sensation is one of perfect peace, mingled with the excitement that strains every nerve to the utmost, if you can conceive of such a combination.”

Eventually, local and international governments began to acknowledge the Wrights and their flying machine was patented

Soon the French and British governments began to show interest in purchasing the Wrights’ Flyers, while American bureaucracy showed little interest. The brothers – and Katharine – traveled to Europe. Here they became celebrities, heralded as understated, oddball “American” heroes. After a demonstration of the Flyer by Wilbur in 1908, a writer for the French paper Le Figaro wrote:

I've seen them! Yes! I have today seen Wilbur Wright and his great white bird, the beautiful mechanical bird...there is no doubt! Wilbur and Orville Wright have well and truly flown.

That year, the American government finally came around, signing a contract with the brothers for the U.S. Army’s first military plane. Now, test flights in Kitty Hawk and elsewhere were drawing scores of reporters. In 1909, they were finally given their due at a homecoming in Dayton, when they were presented with medals by President William Howard Taft himself. According to reports, the brothers – never much for festivities – often snuck off to their workshop during the multi-pronged celebration.

In later years, the brothers – particularly Wilbur, the face of the newly formed Wright Company – became wrapped up in patent wars and big deals. "They got the patent on their flying machine, and then they didn't work to further flight,” says historian Larry Tise. “They worked to protect the patent. They became obsessed with making money and protecting the patent.”

Orville dedicated his life to protecting the brothers' legacy

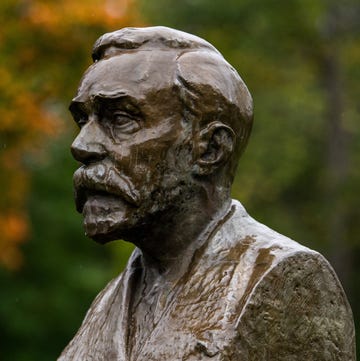

In 1912, Wilbur died at the age of 45 of typhoid fever, which he contracted after eating bad oysters at a hotel in Boston. Orville, always shyer and less worldly, sold the Wright Company soon after, making around $1.5 million in the process. He spent the rest of his life tinkering in his workshop, hanging out with his family and protecting the Wright family legacy.

When Orville died in 1948, he had seen his and his brother’s invention transform transportation, culture and war forever. And to think, it was all the work of two seemingly simple brothers with a soaring dream, unflinching dedication, and faith- in each other.

"Wilbur and Orville were among the blessed few who combined mechanical ability with intelligence in about equal amounts," Wright Brothers biographer Fred Howard once wrote. "One man with this dual gift is exceptional. Two such men whose lives and fortunes are closely linked can raise this combination of qualities to a point where their combined talents are akin to genius."