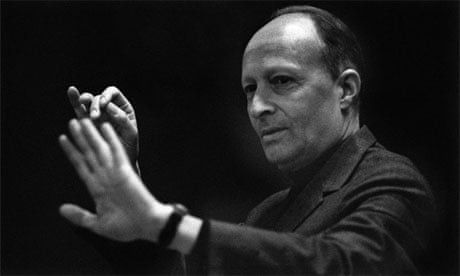

Now, we're perilously close to the boundaries of our self-imposed criteria for this whole series with the Polish composer Witold Lutosławski, since his centenary is celebrated next week (on the 25th, to be precise), but unlike that other prospective centennial this year, one Britten, B (who won't be in this series for reasons of sufficient exposure here and elsewhere). Lutosławski's output is, I think, neither well-known nor well understood enough. It will be, of course, by the end of this 'ere exposition! Or at least, you will have found, I hope, some ear-opening avenues into the work of a composer whose output is among the most complete and coherent of the 20th century.

So let's start, obviously, at the end. Listen to this: Lutosławski's Fourth Symphony, his last major work before his death in 1994, and a piece that symbolises and cements the achievement of his musical language. This is astonishingly eloquent music: a piece that creates a genuinely symphonic discourse through a revivification of some classical principles of achieving unity through diversity, but which is also open and adventurous enough to admit the existence of doubt, conflict, and melancholy – listen to the final few minutes to hear what I mean. It's all a long way from this music, the sophisticated Stravinskyisms and Bartokerie of his First Symphony, composed nearly 50 years earlier, just after the second world war.

Lutosławski's compositional journey involved him finding unique answers to the big existential and musical questions that the 20th century opened up, and his solution, eventually, was to rethink those hoarily old-fashioned ideas of harmony, melody and how you create large-scale musical structures, and he did so in a way that created new kinds of texture, sound, and feeling. (Don't believe me? Try this for size: the opening of Lutosławski's Third Symphony, premiered by the Chicago Symphony and George Solti in 1983; a visceral contrast between vertical violence and sensual but chaotic melody, a juxtaposition that propels the whole half-hour piece.)

But this wasn't a serene progress to musical maturity carried out in an artistic vacuum. Far from it. Lutosławski's life was as enmeshed as any 20th century composer's in the terrifying warp and weft of history and politics. One of his first memories was his father being taken away for execution in Moscow in 1918; his brother didn't survive the second world war, and he spent his war away from his military duties playing in a piano duet with his fellow composer Andrzej Panufnik. Every time they played could have been their last, as they risked performing music banned by the Nazis – like Chopin! – but in their improvisations together, Lutosławski also laid the foundations for some of his later music, like the Variations on a Theme by Paganini.

After the war, Lutosławski had to play a delicate game of creative cat-and-mouse with the communist regime in Poland. As part of the Composers' Union, he paid lip service to the socialist-realist demands of the government, working for Polish Radio and composing jingles, patriotic mass songs, and radio dramas. Even music like his First Symphony did not escape censure, but by the mid 1950s and Poland's political thaw, and the establishment of the Warsaw autumn festival of contemporary music in 1956, Lutosławski was able to begin to compose the music he wanted to. (His Concerto for Orchestra, completed in 1954, is still his most popular piece with orchestras, but Lutosławski said that that brilliant, vital piece did not represent his unadulterated compositional voice; something he only recognised with the music he composed after his Musique Funèbre, from 1958.) But Lutosławski's search for musical truth isn't quite as simple as it seems: under a pseudonym, he wrote pop tunes that were hits in Poland in the late 1950s and early 1960s, something only discovered a decade later; it's still controversial whether his motives were musical or financial in writing these tunes.

From the 1960s, Lutosławski was able to explore the musical terrain that he would make his own. It's a paradoxical combination of compositional freedom with structural rigour that finds a sometimes subtle, sometimes sensual, and occasionally visceral poetry in pieces like Jeux Venitiens, his Livre pour Orchestre, or the Second Symphony. If you listen to what Lutosławski said in interviews and public statements, you'll understand these pieces, just like all those that came after, as purely abstract investigations of the things that music can say that nothing else can: ie that there's no connection between the social, political, or personal dimensions of Lutosławski's life and the music he wrote.

Mstislav Rostropovich didn't agree, though. He regarded the Cello Concerto that Lutosławski wrote for him in 1970 as an epic confrontation between an individual and an oppressive mass, in which the cello's voice is symbolically squashed by outbursts in the brass and orchestral explosions, a staging of the essential tensions of living in a communist system. Not so, said Lutosławski. Then there's Lutosławski's distinctive but misunderstood technique of "controlled aleatoricism", a magnificently obfuscatory term for something incredibly simple: basically, giving orchestral players material to play without precise rhythmic co-ordination, so you can create textures in which you know what pitches you're going to hear, but not exactly in what combination or at what speed. It's an easy way of conjuring a controlled chaos and a complex but relatively static texture, and you hear it in the Ad Libitum sections of his Chain II for violin and orchestra, or passages in nearly every work he composed since the 1960s, starting with Jeux Venitiens. It's misunderstood because it's not at all a way of giving musicians license to improvise, and it's far too simplistic to equate this delicate musical freedom with any social or political agenda. Nonetheless, it was one of the ways that Lutosławski found to open up his music to a more unpredictable soundworld, while retaining an essential compositional control.

It's a technique that's also used throughout the Third Symphony, a piece composed during Poland's period of martial law in the early 1980s, and work that creates an irresistible lyricism in some of the most powerfully melodic string writing of the late 20th century, a song that sings with a completely convincing but utterly novel expressivity. And Lutosławski at last admitted that although it wasn't his intention that this piece should reflect Poland's and Solidarity's contemporary struggle for greater freedoms, if people chose to interpret it that way, he wouldn't tell them not to. Sounds a pretty small aesthetic change? It's important, I think. I've been in Poland recording interviews for Radio 3's Music Matters, which is dedicated to Lutosławski on Saturday 19 January, and I met Grzegorz Michalski, president of the Lutosławski Society, who told me something that contradicted everything I've read about Lutosławski's supposed lack of direct political engagement. He was affiliated, albeit in secret, to one of Solidarity's committees, and was the only musician to hold such a position. And he refused to play ball with the government in the early 1980s, withdrawing from his public activities. (Lutosławski had a telling metaphor for all this: he said that working with the regime had been like wearing shoes that were too small, and that once they had come off, once he stopped trying to play games with his public persona and the government, he couldn't put them on again.) It was also around this time that he started giving grants to young composers so that they could study abroad, and paying for essential medical operations; work he often did unacknowledged and without any public fanfare.

There's always a debate to be had around the relationship between a composer's life and their music, and if the composer says there's no connection, we need to listen to them. But it's more complicated that Lutosławski suggests. You don't have to look for clues in the communist regime to find the foundations of Lutosławski's harmonic language, but the concentration, ravishment, and refinement of his music could not have been written by anyone else at any other time. Lutosławski the man was as immaculate, fastidious, and restrained as his music. And just as his works don't contain any extra notes, Lutosławski was someone who only spoke when he had something to say, according to Marcin Bogusławski, his stepson.

And there's something else too. Lutosławski's attitude to life – his unswerving fealty to a daily regimen of work, work, and more work, his sharing of his talents and the material wealth he earned, and his insistence on absolute silence in his home and the study where he worked – has an almost monastic quality. And according to Michalski, Lutosławski was a religious man, even if he didn't write any explicitly religious or liturgical works. Because his wife Danuta (to whom he was devoted, and who died of a broken heart just weeks after his death) had divorced before marrying him, Witold could not take communion in the Polish church. That mattered to him, Michalski said, and to compensate, every year he would stay for a week with his cousin at his monastery to "clean his soul". That spiritual dimension, I think, is what's behind the transcendent refinement you hear in his music: it's there throughout the Fourth Symphony, it's present in the radiant, deceptive simplicity of his late song-cycle Chantefleurs et Chantefables, and in the limpid drama of the Piano Concerto, composed for Krystian Zimerman. Lutosławski said that to write music was to go "fishing for souls", searching for listeners like him, for whom his music would resonate somewhere deep inside them. It's a strikingly spiritual way of describing his supposedly abstract art – see if he has caught yours …

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion