1941 (film)

| 1941 (film) | |

|---|---|

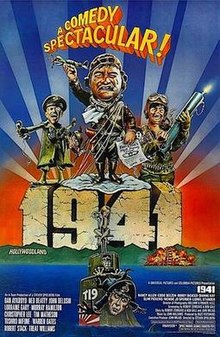

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Steven Spielberg |

| Screenplay by | |

| Story by |

|

| Produced by | Buzz Feitshans |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | William A. Fraker |

| Edited by | Michael Kahn |

| Music by | John Williams |

| Color process | Metrocolor |

Production company | A-Team Productions |

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures (North America) Columbia Pictures (International) |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 118 minutes 146 minutes (director's cut) |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $35 million[1] |

| Box office | $94.9 million[1] |

1941 is a 1979 American war comedy film directed by Steven Spielberg and written by Robert Zemeckis and Bob Gale. The film stars an ensemble cast including Dan Aykroyd, Ned Beatty, John Belushi, John Candy, Christopher Lee, Tim Matheson, Toshiro Mifune, Robert Stack, Nancy Allen, and Mickey Rourke in his film debut. The story involves a panic in the Los Angeles area after the December 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor.

Co-writer Gale stated the plot is loosely based on what has come to be known as the Great Los Angeles Air Raid of 1942, as well as the bombardment of the Ellwood oil refinery, near Santa Barbara, by a Japanese submarine. Many other events in the film were based on real incidents, including the Zoot Suit Riots and an incident in which the U.S. Army placed an anti-aircraft gun in a homeowner's yard on the Maine coast.[2]

The film received heavily mixed reviews from critics with criticism towards the script, pacing and humor but praise towards the visual effects, sound, production design, John Williams's score and cinematography.

1941 was not as financially, nor critically successful as many of Spielberg's other films; because of this, the film has often been erroneously referred to as a box office bomb and a failure. 1941 was actually a box office success and it received belated popularity after an expanded version aired on ABC in the 1980s, with subsequent television broadcasts and home video reissues, raising it to cult status.[3]

Plot[edit]

On Saturday, December 13, 1941, at 7:01 a.m. (six days after the attack on Pearl Harbor), an Imperial Japanese Navy submarine, commanded by Akiro Mitamura and carrying Kriegsmarine officer Wolfgang von Kleinschmidt, surfaces off the Californian coast. Wanting to destroy something "honorable" in Los Angeles, Mitamura decides to target Hollywood. Later that same morning, a 10th Armored Division M3 Lee tank crew, consisting of Sergeant Frank Tree, Corporal Chuck Sitarski, and Privates Foley, Reese, and Henshaw, are having breakfast at a cafe in Los Angeles where dishwasher Wally Stephens and his friend Dennis DeSoto work. Wally is planning to enter a dance contest at a club that evening with his girlfriend, Betty Douglas. Sitarski, who has an extremely short temper, instantly dislikes Wally and trips him, causing a fight and leaving Wally humiliated.

United States Army Air Forces Captain Wild Bill Kelso wildly cruises his Curtiss P-40 Warhawk around the western states in search of Japanese forces, leaving chaos in his wake. Meanwhile, in Los Angeles, Major General Joseph W. Stilwell attempts to calm the public, who believe Japan will attack California. During a press conference at Daugherty Field in Long Beach, Captain Loomis Birkhead, Stilwell's aide, meets his old flame Donna Stratton, who is General Stilwell's new secretary. Aware that Donna is sexually aroused by airplanes, Birkhead lures her into the cockpit of a B-17 bomber to seduce her. When his attempt fails, Donna punches him; as he falls, Birkhead accidentally releases a bomb, which rolls against the conference's grandstand and explodes, though Stilwell and the crowd escape unhurt.

At the Santa Monica oceanside home of her father Ward Douglas and his wife Joan, Betty and her friend Maxine Dexheimer, who have just become USO hostesses, tell Wally that they are only allowed to dance with servicemen as they are now the only male patrons allowed in the club. Wally hides in the garage when Ward, who disapproves of him, appears. Sgt. Tree and his crew arrive and inform Ward and Joan that the army wants to install an anti-aircraft battery in their yard. Sitarski begins flirting with Betty, and Wally falls from the loft where he was hiding. Wally and Sitarski recognize each other from the cafe, and the Sgt. Tree’s crew dumps Wally into a passing garbage truck after ejecting him from the premises.

Meanwhile, the Japanese submarine has become lost trying to find Los Angeles after their compass malfunctions. A landing party goes ashore and captures lumberjack Hollis "Holly" Wood. Aboard the sub, Hollis is searched and the crew is excited to find a small toy compass, which Hollis swallows. After the crew attempts to make Hollis excrete the compass by forcing him to drink prune juice, he escapes from the submarine.

Ward's neighbor, Angelo Scioli of the Ground Observer Corps, installs Claude and Herb in the Ferris wheel at the Ocean Front Amusement Park to scout for enemy aircraft. Determined to get Donna into an airplane, Birkhead drives her to the 501st Bomb Disbursement Unit in Barstow, where the mentally unstable Colonel "Mad Man" Maddox lets them borrow a plane. Donna, aroused from finally being in an airplane, begins to ravish Birkhead during the flight.

At the USO club, Sitarski drags Betty into the dance. Wally sneaks in and reunites with Betty. They win the dance contest, and the short-tempered Sitarski punches Wally, setting off a brawl between soldiers, sailors and zoot suiters which spills into the street and becomes a riot. Sgt. Tree and his crew break up the melee, just before L.A. goes on high alert when Birkhead and Donna fly over the city and anti-aircraft batteries open fire on them. Kelso pursues and shoots it down, causing it to land into the La Brea Tar Pits. Claude and Herb shoot down Kelso's passing P-40 after mistaking it for a Japanese Zero; Kelso crashlands in the city, where he informs the military authorities about the Japanese sub he spotted at the pier. Wally is put in command of the tank after Tree is accidentally incapacitated, and rescues Betty while Sitarski is accosting her. After Kelso's alert, Wally, Betty, Dennis and the tankers set off for the pier, followed by Kelso on a motorcycle.

At the Douglas' home, Ward spots the surfaced submarine and begins firing the anti-aircraft gun at it, wrecking his whole house in the process. The sub returns fire, hitting the Ferris wheel, which rolls into the ocean. When von Kleinschmidt tries to force the sub to retreat early, Mitamura throws him overboard. The tank arrives and then sinks when the submarine torpedoes the pier. Kelso jumps off the pier and swims to the submarine, where he is captured by the Japanese. The captain considers the mission an honorable success, and the sub departs.

The next morning, Stilwell and soldiers arrive at the remains of the Douglas home, where the other protagonists have gathered. Ward vows that their Christmas will not be ruined by the enemy; to symbolize his point, he nails a Christmas wreath to his front door, causing his unstable house to collapse down the hillside. Stilwell, observing the disheveled crowd arguing, tells Sgt. Tree, "It's going to be a long war."

Cast[edit]

- Dan Aykroyd as Motor Sergeant Frank Tree

- Ned Beatty as Ward Douglas

- John Belushi as Captain Wild Bill Kelso

- Lorraine Gary as Joan Douglas

- Murray Hamilton as Claude Crumn

- Christopher Lee as Captain Wolfgang Von Kleinschmidt

- Tim Matheson as Captain Loomis Birkhead

- Toshiro Mifune as Commander Akiro Mitamura

- Warren Oates as Colonel "Madman" Maddox

- Robert Stack as Major General Joseph W. Stilwell

- Treat Williams as Corporal Chuck Sitarski

- Nancy Allen as Donna Stratton

- Bobby Di Cicco as Wally Stephens

- Eddie Deezen as Herbie Kazlminsky

- Walter Olkewicz as Private Hinshaw

- Dianne Kay as Betty Douglas

- Slim Pickens as Hollis P. Wood

- Kerry Sherman as USO Girl

- Wendie Jo Sperber as Maxine Dexheimer

- John Candy as Private First Class Foley

- John Voldstad as USO Nerd

- Perry Lang as Dennis DeSoto

- Geno Silva as Martinez

- Patti LuPone as Lydia Hedberg

- Whitney Rydbeck as Daffy

- Penny Marshall as Miss Fitzroy

- Lucinda Dooling as Lucinda

- Frank McRae as Private Ogden Johnson Jones

- Steven Mond as Gus Douglas

- Dub Taylor as Mr. Malcomb

- Luis Contreras as Zoot Suiter

- Lionel Stander as Angelo Scioli

- Michael McKean as Willy

- Susan Backlinie as Polar Bear Woman

- David Lander as Joe

- Joe Flaherty as Sal Stewart / Raoul Lipschitz

- Don Calfa as Telephone Operator

- Iggie Wolfington as Meyer Mishkin

- Lucille Benson as Gas Mama

- Elisha Cook Jr. as The Patron

- Hiroshi Shimizu as Lieutenant Ito

- Rita Taggart as Reporter

- Maureen Teefy as USO Girl

- Akio Mitamura as Ashimoto

- Mickey Rourke as Private Reese

- Samuel Fuller as Commander Hawkins

- Audrey Landers as USO Girl

- John Landis as Mizeraney

- Dick Miller as Officer Miller

- Donovan Scott as Kid Sailor

- Andy Tennant as Babyface

- Jack Thibeau as Lieutenant Reiner

- Jerry Hardin as Map Man

- Robert Houston as Corporal Taylor

- James Caan as Fighting Sailor (Uncredited)

- Sydney Lassick as Salesman (Uncredited)

- Debbie Rothstein as USO Girl, Jitterbugger (Uncredited)

Production[edit]

According to Steven Spielberg's appearance in the documentary Stanley Kubrick: A Life in Pictures, Kubrick suggested that 1941 should have been marketed as a drama rather than a comedy. The chaos of the events following the Pearl Harbor attack in 1941 is summarized by Dan Aykroyd's character, Sgt. Tree, who repeatedly states, 'If there's one thing I can't stand seeing, it's Americans fighting Americans."[2]

Robert Zemeckis originally pitched the concept to John Milius as a serious depiction of the real-life 1942 Japanese bombardment of Ellwood, California; the subsequent false alarm of a Japanese air raid on Los Angeles; and the 1943 Zoot Suit Riots, titled The Night the Japs Attacked. After development of the film transferred from Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer to Universal Pictures, executives insisted that the title be changed to Rising Sun to avoid the use of the derogatory term "Jap." The story became a comedy after Steven Spielberg became involved as director, and the script was rewritten during the production of Close Encounters of the Third Kind in 1977. The characters of Claude Crumm and Herb Kaziminsky were originally written with The Honeymooners co-stars Jackie Gleason and Art Carney in mind. Hollis P. "Holly" Wood and "Wild Bill" Kelso were originally minor characters before Belushi and Pickens were cast.[4]

1941 is also notable as one of the few American films featuring Toshiro Mifune, a popular Japanese actor. It is also the only American film in which Mifune used his own voice in speaking Japanese and English. In his previous movies, Mifune's lines were dubbed by Paul Frees.[2]

John Wayne, Charlton Heston, and Jimmy Stewart were originally offered the role of Major General Stilwell, with Wayne still considered for a cameo in the film.[4] After reading the script, Wayne decided not to participate due to ill health, but also urged Spielberg not to pursue the project, as both he and Heston felt the film was unpatriotic. Spielberg recalled, "[Wayne] was really curious and so I sent him the script. He called me the next day and said he felt it was a very un-American movie, and I shouldn't waste my time making it. He said, 'You know, that was an important war, and you're making fun of a war that cost thousands of lives at Pearl Harbor. Don't joke about World War II'."[5] Initially Spielberg wanted Meyer Mishkin to portray himself, but had to cast Iggie Wolfington because of Screen Actors Guild regulations barring film agents from working as actors.[4]

Susan Backlinie, the first victim in Spielberg's Jaws, appeared as the woman seen swimming nude at the beginning of the film.[2] The gas station that Wild Bill Kelso accidentally blows up early in the film is the same one seen in Spielberg's 1971 TV film, Duel, with Lucille Benson appearing as the proprietor in both films. Inadvertent comedic effects ensued when John Belushi, in character as Captain Wild Bill Kelso, unintentionally fell off the wing of his airplane, landing on his head. It was a real accident and Belushi was hospitalized for several days, but Spielberg left the shot in the movie as it fit Kelso's eccentric character.[6]

During the USO riot scene, when a military police officer is tossed into the window of a restaurant from the ladder of a fire engine, Belushi is seen eating spaghetti, in makeup to resemble Marlon Brando in The Godfather, whom he famously parodied in a sketch on Saturday Night Live. Belushi told Spielberg he wanted to appear as a second character and the idea struck Spielberg as humorous.[2] At the beginning of the USO riot, one of the uncredited "extras" dressed as a sailor is actor James Caan. Mickey Rourke makes his first screen appearance in the film as Private First Class Reese of Sgt. Tree's tank group.[7]

The M3 tank Lulu Belle (named after a race horse) and fashioned from a mocked-up tractor, paid homage to its forebear in Humphrey Bogart's 1943 movie Sahara where an authentic M3 named Lulubelle was prominently featured.[8]

Renowned modelmaker Greg Jein worked on the film, and would later use the hull number "NCC-1941" for the starship USS Bozeman in the Star Trek: The Next Generation episode "Cause and Effect".[9] Paul De Rolf choreographed the film.[10]

1941 is dedicated to the memory of Charlsie Bryant, a longtime script supervisor at Universal Studios. She had worked on both Jaws and Close Encounters, and would have reprised those duties with this film had she not unexpectedly died.[11]

Special effects[edit]

The Oscar-winning team of L.B. Abbott and A.D. Flowers were in charge of the special effects on 1941. The film is widely recognized for its Academy Award-nominated special-effects laden progressive action and camera sequences.[12][N 1]

Trailer[edit]

The advance teaser trailer for 1941, directed by the film's executive producer/co-story writer John Milius, featured a voice-over by Aykroyd as Belushi's character Kelso (here erroneously named "Wild Wayne" and not "Wild Bill"), after landing his plane, gives the viewers a pep-talk encouraging them to join the United States Armed Forces, lest they find one morning that the country will have been taken over (for instance, "the street signs will be written in Japanese!").[14]

Music[edit]

The musical score for 1941 was composed and conducted by John Williams. The titular march is used throughout the film and is perhaps the most memorable piece written for it. (Spielberg has said it is his favorite Williams march.) The score also includes a swing composition titled "Swing, Swing, Swing" composed by John Williams. In addition, the score includes a sound-alike version of Glenn Miller's "In the Mood", and two 1940s recordings by The Andrews Sisters, "Daddy" and "Down by the Ohio". The Irish tune "The Rakes of Mallow", is heard during the riot at the USO.

The LaserDisc and DVD versions of the film have isolated music channels with additional cues not heard on the first soundtrack album.

In 2011, La-La Land Records, in conjunction with Sony Music and NBCUniversal, issued an expanded 2-CD soundtrack of the complete John Williams score as recorded for the film, plus never-before-heard alternative cues, source music, and a remastered version of the original album. Disc One, containing the film score, presents the music as Williams originally conceived based on early cuts of the movie.[15][16][17]

Release[edit]

The film was previewed at approximately two and a half hours, but Columbia Pictures and Universal Pictures, which both had a major financial investment, felt it was too long to be a blockbuster. The initial theatrical release was edited down to just under two hours, against Spielberg's wishes.[18] Additionally, the release of the film was delayed by a month after a preview screening to investors in Dallas received negative reviews to allow Spielberg to reedit the first 45 minutes of the film.

The film premiered at the Cinerama Dome in Hollywood on December 13, 1979, before opening to the public the following day.[19]

Home media[edit]

After the success of his 1980 "Special Edition" of Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Spielberg was given permission to create his own "extended cut" of 1941 to represent his original director's cut. This was done for network television (it was only shown on ABC once, but it was seen years later on The Disney Channel). It was first released on VHS and Betamax in 1980 from MCA Videocassette Inc. and from MCA Home Video in 1986 and 1990. A similar extended version (with additional footage and a few subtle changes) was released on LaserDisc in 1995. It included a 101-minute documentary featuring interviews with Spielberg, executive producer John Milius, writers Robert Zemeckis and Bob Gale, editor Michael Kahn, composer John Williams and others involved. This set also included an isolated music score, three theatrical trailers, deleted scenes, photo galleries, and reviews of the movie.

This cut was later released on VHS in 1998, and later on DVD in 1999 and was rereleased on DVD again in May 2002.[20][21] The DVD includes all features from the 1995 Laserdisc Set. It was released again on DVD in 2000 in a John Belushi box set along with the collector's editions of Animal House and The Blues Brothers.

On October 14, 2014, Universal Pictures released 1941 on Blu-ray as part of their Steven Spielberg's Director's Collection box set. The disc features both the theatrical (118 minutes) and extended version (146 minutes) of the film, a documentary of the making of the film, production photographs (carried over from the LaserDisc collector's edition), and theatrical trailers, although the isolated score that was included on the Laserdisc and DVD releases is not present on the Blu-ray. The standalone Blu-ray version was released on May 5, 2015.

Heavy Metal and Arrow Books produced a magazine-sized comics tie-in to the film, by Allen Asherman, Stephen R. Bissette, and Rick Veitch, which rather than being a straight adaptation, varies wildly and humorously from the film. Spielberg wrote the book's introduction.[22]

Reception[edit]

Box office[edit]

"It is down in the history books as a big flop, but it wasn't a flop. The movie didn't make the kind of money that Steven's other movies, Steven's most successful movies have made, obviously. But the movie was by no means a flop. And both Universal and Columbia have come out of it just fine."

—Bob Gale[2]

During its theatrical run, 1941 had earned $23.4 million in theatrical rentals from the United States and Canada.[23] Because 1941 grossed significantly less than Jaws and Close Encounters of the Third Kind, the film has been erroneously thought to be a box office disaster, but in actuality, 1941 grossed $90 million worldwide and returned a profit, making it a success.[24]

Critical reaction[edit]

Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune gave the film two and a half out of four stars in which he applauded the film's visual effects, but stated "[T]here is so much flab here, including endless fistfights and huge dance production numbers that become meaningless after a few minutes."[25] Writing in his review for The New York Times, Vincent Canby wrote "There are too many characters who aren't immediately comic. There are too many simultaneous actions that necessitate a lot of cross-cutting, and cross-cutting between unrelated anecdotes can kill a laugh faster than a yawn. Everything is too big...The slapstick gags, obviously choreographed with extreme care, do not build to boffs; they simply go on too long. I'm not sure if it's the fault of the director or of the editor, but I've seldom seen a comedy more ineptly timed."[26] Similarly, Variety labeled the movie as "long on spectacle, but short on comedy" in which the magazine felt "1941 suffers from Spielberg's infatuation with physical comedy, even when the gags involve tanks, planes and submarines, rather than the usual stuff of screen hijinks. Pic is so overstuffed with visual humor of a rather monstrous nature that feeling emerges, once you've seen 10 explosions, you've seen them all."[27]

Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times gave the film one and a half stars out of four, writing that the film "feels forced together chaotically, as if the editors wanted to keep the material moving at any cost. The movie finally reduces itself to an assault on our eyes and ears, a nonstop series of climaxes, screams, explosions, double-takes, sight gags, and ethnic jokes that's finally just not very funny." He labeled the film's central problem on having been "never thought through on a basic level of character and story."[28] Charles Champlin, reviewing for the Los Angeles Times, commented "If 1941 is angering (and you may well suspect that it is), it is because the film seems merely an expensive indulgence, begat by those who know how to say it, if only they had something to say."[29] Dave Kehr of The Chicago Reader called it "a chattering wind-up toy of a movie [that] blows its spring early on. The characters are so crudely drawn that the film seems to have no human base whatsoever...the people in it are unremittingly foolish, and the physical comedy quickly degenerates into childish destructiveness."[30]

Years later, the film would be re-appraised by critics like Richard Brody of The New Yorker, who claimed it was "the movie in which [Spielberg] came nearest to cutting loose"[31] and "the only movie where he tried to go past where he knew he could...its failure, combined with his need for success, inhibited him maybe definitively."[32] Jonathan Rosenbaum of The Chicago Reader would hail 1941 as Spielberg's best film until 2001's A.I. Artificial Intelligence, writing that he was impressed by the virtuosity of 1941 and argued that its "honest mean-spiritedness and teenage irreverence" struck him as "closer to Spielberg's soul" than more popular and celebrated works like E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial and The Color Purple.[33]

According to Jack Nicholson, director Stanley Kubrick allegedly told Spielberg that 1941 was "great, but not funny."[34] Spielberg joked at one point that he considered converting 1941 into a musical halfway into production and mused that "in retrospect, that might have helped."[35] In a 1990 interview with British film pundit Barry Norman, Spielberg admitted that the mixed reception to 1941 was one of the biggest lessons of his career, citing personal arrogance that had gotten in the way after the runaway success of Jaws and Close Encounters of the Third Kind. He also regretted not ceding control of 1941's action and miniature sequences (such as the Ferris wheel collapse in the film's finale) to second unit directors and model units, something which he would do in his next film, Raiders of the Lost Ark.[36] He also said "Some people think that was an out-of-control production, but it wasn't. What happened on the screen was pretty out of control, but the production was pretty much in control. I don't dislike the movie at all. I'm not embarrassed by it — I just think that it wasn't funny enough."[37]

On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, the film received an approval rating of 41%, based on 27 reviews, with an average rating of 5.1/10. The critical consensus reads, "Steven Spielberg's attempt at screwball comedy collapses under a glut of ideas, confusing an unwieldy scope for a commensurate amount of guffaws."[38] On Metacritic, the film has a weighted average score of 34 out of 100, based on 7 critics, indicating "generally unfavorable reviews".[39]

Accolades[edit]

The film received three nominations at the 1980 Academy Awards.[40]

| Award | Category | Nominee(s) | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Awards[40] | Best Cinematography | William A. Fraker | Nominated |

| Best Sound | Robert Knudson, Robert Glass, Don MacDougall and Gene S. Cantamessa | ||

| Best Visual Effects | William A. Fraker, A. D. Flowers and Gregory Jein |

American Film Institute nominated the film in AFI's 100 Years...Laughs. [41]

References[edit]

Notes[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ a b "1941". The Numbers. Retrieved September 27, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f The Making of 1941. Universal Studios Home Entertainment. 1996. Archived from the original on December 6, 2020 – via YouTube.

- ^ "What is Cult Film?". for68.com Beijing ICP. January 13, 2006. Archived from the original on February 19, 2009. Retrieved April 10, 2009.

- ^ a b c "1941". AFI Catalog. Archived from the original on July 21, 2019. Retrieved November 12, 2021.

- ^ "John Wayne - John Wayne Urged Steven Spielberg Not To Make War Comedy." contactmusic.com. 2 December 2011. Retrieved: December 2, 2011.

- ^ Erickson, Glenn. "1941 - A giant comedy, only with guns!" DVD Savant, 1999. Retrieved: December 16, 2012.

- ^ Heard 2006, p. 22.

- ^ Nelson, Erik. "The Perfect Double Bill:'The Hurt Locker' and Bogart's 1943 'Sahara'." Salon, January 12, 2010.

- ^ "First Person: Greg Jein." CBS Entertainment. Retrieved: October 19, 2011.

- ^ Washington, Arlene (June 26, 2017). "Paul De Rolf, Choreographer for 'Petticoat Junction' and Spielberg's '1941,' Dies at 74". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved July 20, 2017.

- ^ "Review of 1941 (1979)." Time Out, New York.

- ^ Culhane 1981, pp. 126–129.

- ^ Dolan 1985, pp. 98–99.

- ^ "Trailer for 1941" on YouTube. Retrieved: October 10, 2012.

- ^ "La-La Land Records, 1941." Archived 2011-10-05 at the Wayback Machine La-La Land Records, September 27, 2011. Retrieved: October 8, 2011.

- ^ 1941: Complete Original Motion Picture Soundtrack, Liner notes by Mike Matessino, La-La Land Records/Sony Music/NBCUniversal, 2011.

- ^ "JWFan Exclusive – Interview with Producer Mike Matessino about '1941'." JWFan.com, September 26, 2011. Retrieved: October 8, 2011.

- ^ McBride 2011, p. 298.

- ^ "'1941' Gets Its Delayed Preem Dec. 13 At Dome". Daily Variety. November 30, 1979. p. 2.

- ^ Liebenson, David (February 12, 1998). "Spielberg's Disaster Movie". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved October 18, 2020.

- ^ Hunt, Bill (March 23, 1999). "1941 (Collector's Edition)". DigitalBits. Archived from the original on April 2, 2012. Retrieved September 16, 2011.

- ^ 1941: The Illustrated Story. Heavy Metal/Arrow Books. December 1979. ISBN 0930834089.

- ^ "Big Rental Films of 1980". Variety. January 14, 1981. p. 29.

- ^ McBride 2011, p. 309.

- ^ Siskel, Gene (December 14, 1979). "Special effects win the battle, but ill effects lose the war for '1941'". Chicago Tribune. Section 4, pp. 1, 4 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (December 14, 1979). "Film: California Goes To War in '1941'". The New York Times. Retrieved October 18, 2020.

- ^ "Film Reviews: 1941". Variety. December 19, 1979.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (December 14, 1979). "1941 (1979) movie review & film summary". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved October 18, 2020 – via RogerEbert.com.

- ^ Champlin, Charles (December 23, 1979). "Spielberg's Pearl Harbor". Los Angeles Times. Part IV, p. 1 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Kehr, Dave. "1941 (1979) capsule review". Chicago Reader. Retrieved March 27, 2021 – via chicagoreader.com.

- ^ Ehrlich, David (December 11, 2017). "Film Critics Pick Steven Spielberg's Best Movies — IndieWire Critics Survey". IndieWire. Retrieved March 27, 2021 – via indiewire.com.

- ^ @tnyfrontrow (March 20, 2019). "1941 is the only movie where he tried to go past where he knew he could; its failure, combined with his need for success, inhibited him maybe definitively" (Tweet). Retrieved March 27, 2021 – via Twitter.

- ^ Rosenbaum, Jonathan (December 16, 1993). "Gentle Persuasion". Chicago Reader. Retrieved March 27, 2021 – via chicagoreader.com.

- ^ Ciment, Michel; Adair, Gilbert; Bononno, Robert, eds. (2003). "Interview: Jack Nicholson". Kubrick: The Definitive Edition. New York: Faber & Faber. p. 297. ISBN 978-0-571-21108-1.

- ^ Bonham and Kay 1979

- ^ Schickel, Richard (Director) (July 9, 2007). Spielberg on Spielberg (Documentary).

- ^ Breznican, Anthony (December 2, 2011). "Steven Spielberg: The EW interview". Entertainment Weekly.

- ^ "1941 (1979)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Retrieved April 16, 2024.

- ^ "1941 Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Retrieved May 6, 2018.

- ^ a b "The 52nd Academy Awards (1980) Nominees and Winners". Oscars.org.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years..Laughs" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 11, 2019.

Bibliography[edit]

- Bonham, Joseph; Kay, Joe, eds. (1979). "Bombs Awaayyy!!! The Official 1941 Magazine". New York: Starlog Press.

{{cite magazine}}: Cite magazine requires|magazine=(help) - Bonham, Joseph; Kay, Joe, eds. (1979). "1941: The Poster Book". New York: Starlog Press.

{{cite magazine}}: Cite magazine requires|magazine=(help) - Clarke, James (2004). Steven Spielberg. London: Pocket Essentials. ISBN 1-904048-29-3.

- Culhane, John (1981). Special Effects in the Movies: How They Do it. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-28606-5.

- Crawley, Tony (1983). The Steven Spielberg Story. New York: William Morrow. ISBN 0-688-02510-2.

- Dolan Jr., Edward F. (1985). Hollywood Goes to War. London: Bison Books. ISBN 0-86124-229-7.

- Erickson, Glenn; Trainor, Mary Ellen (1980). The Making of 1941. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-28924-2.

- Freer, Ian (2001). The Complete Spielberg. New York: Virgin Books. ISBN 0-7535-0556-8.

- Heard, Christopher (2006). Mickey Rourke: High and Low. Medford, New Jersey: Plexus Publishing. ISBN 978-0-85965-386-2.

- McBride, Joseph (2011). Steven Spielberg: A Biography (2nd ed.). Jackson, Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-60473-836-0.

- Sinyard, Neil (1986). The Films of Steven Spielberg. London: Bison Books. ISBN 0-86124-352-8.

- "Steven Spielberg: The Collector's Edition". Empire. 2004.

Further reading[edit]

- "Review of 1941". Time Out New York. 1979. Archived from the original on December 21, 2007. Retrieved January 25, 2008.

External links[edit]

- 1941 at AllMovie

- 1941 at the American Film Institute Catalog

- 1941 at Box Office Mojo

- 1941 at IMDb

- 1941 at the TCM Movie Database

- 1941 at Letterboxd

- 1941 at Rotten Tomatoes

- 1979 films

- 1979 action comedy films

- 1970s Christmas comedy films

- 1970s screwball comedy films

- 1970s war comedy films

- American action comedy films

- American Christmas comedy films

- American screwball comedy films

- American World War II films

- Columbia Pictures films

- 1970s English-language films

- Films scored by John Williams

- Films directed by Steven Spielberg

- Puppet films

- Films set in 1941

- Films set in Los Angeles

- Films set on the United States home front during World War II

- Films shot in Oregon

- Military humor in film

- Pacific War films

- Pearl Harbor films

- Films with screenplays by Robert Zemeckis

- Films with screenplays by Bob Gale

- American slapstick comedy films

- Universal Pictures films

- Films adapted into comics

- Japan in non-Japanese culture

- Films produced by Buzz Feitshans

- 1970s American films