INTRODUCTION

One might think that defining African Cinema would be an easy enough task. Spend a little time in the attempt, however, and the difficulty in doing so definitively soon becomes evident. A film set in Africa, shot in Africa by an African crew, and starring an African cast is certainly an example of African cinema. Is a film shot by a Frenchman in colonial French West Africa an African film, however? If not necessarily, is it if that French director employs an otherwise native African cast and crew and ends up becoming a citizen of Africa? And what about the Africa descendants of immigrants from India or China who, born and bred in Africa, go on to pursue film careers there. Africa, surely, has room for immigrants just as any other continent. White South African filmmakers might be dismissed as “colonial filmmakers” but are they really any more so than the white filmmakers of Hollywood?

The laziness and happily unexamined ignorance of non-African critics and cineastes has long been a source of personal frustration. Whilst a boutique streaming service like MUBI has a good track record for showcasing films from around the world and produced throughout film’s history, the more popular streaming-sites-for-basics (i.e. Amazon, Hulu, and Neflix) inflate their vast collections with mediocre films that rarely aspire to be more than middle-brow. The Criterion Collection, gatekeeper of the canon, has rarely ventured outside of the Western world except to recognize mid-20th century Japanese cinema. Thankfully, they gave a platform to African film lover Martin Scorsese, who used his World Cinema Project to expose Criterion‘s artistic conservatives to some of the best, neglected films from Asia, Europe, Latin America, and Africa. Since 2012, the best source for classic African films online has been the African Film Library.

African cinema remains, though, overlooked and deserves far more respect and serious attention that it receives in most quarters. The Pan-African Film Festival is taking place right now. In non pandemic years, its always a fun event and frequently provides film-goers an opportunity to interact with African filmmakers and actors that they would otherwise have little chance to. This year, it’s online, which won’t match the experience of seeing the films in theaters full of excited and engaged audiences — but hopefully it will make it easier for Angelenos who have ignored the last 29 years of the festival to watch something from the comfort of their homes.

And so — because Googling “African films” still, exasperatingly yields results like African Queen, Black Panther, Legend of Tarzan, and Rampage, I have undertaken the unenviable but hopefully appreciated task of writing a brief history of African cinema and a guide to notable African directors both for your use and for mine.

EARLY CINEMA IN AFRICA

What, exactly, counts as the first motion picture is the subject of debate and disagreement from film scholars. One of the earliest examples of a motion picture, though, is French inventor Louis Le Prince‘s Roundhay Garden Scene from 1888. It is comprised of pictures that convey motion for its short length of just three seconds. In 1893, a mere five years later, Breton filmmaker William Kennedy-Laurie Dickson‘s Blacksmith Scene, filmed for the Edison Manufacturing Company, was the first kinetoscope film afforded a public screening. In 1895, capitalist Woodville Latham, an American, had the bright idea of charging admission and thus, cinema as we know it today, had assumed a recognizable form of capitalized distribution and consumption.

Film came to Africa just a year later, when French filmmakers Auguste and Louis Lumière publicly screened their actuality films in Egypt and Tunisia. In 1897, Louis Lumière filmed Le Chevrier Marocain in Morocco. By 1905, all of Africa had been colonized except Ethiopia. In all cases except Liberia — colonized as it was by former American slaves — the colonizers were European. Whilst the UK and France had the largest colonial presence, Germany, Spain, Belgium, and Portugal also had African colonies and in most, filmmakers in service of their colonial masters began producing documentaries, newsreels, and propaganda about their colonial subjects. Amongst the earliest of these colonial efforts were Carl Müller‘s Lomé, filmed in Togoland (modern day Togo) in 1906, Ernesto de Albuquerque‘s A cultura do Cacau em Sao Tome in 1909, and Cardoso Furtado‘s Serviçal e Senhor in 1910.

Before long, colonial filmmakers shot feature films in Africa. Amongst the first of these features shot in Africa were Robinson Christian Englestoft Nissen‘s Die Groot Diamantroof van Kimberley, filmed in South Africa in 1911, and Luitz-Morat and Pierre Régnier‘s Les cinq gentlemen maudits, shot in Tunisia in 1919. In 1924, Albert Samama Chikly (ألبير شمامة شيكلي) directed عين الغزال (or La fille de Carthage), perhaps the first feature film made by a native African, in Chikly’s case, a Tunisian Jew. It was followed, not long after, by 1927’s Laila, co-directed by Turkish filmmaker Vedat Örfi Bengü and Italian filmmaker Estafan Rosti, both of whom had emigrated to Egypt.

Independence was integral to the development of local African film industries. Egypt became an independent state in 1922. Studio Misr (ستوديو مصر) was founded by economist and banker Talaat Harb Pacha (طلعت حرب باشا) in 1934. Egypt’s cinema quickly came to dominate the Arab world. Meanwhile, in Britain’s remaining colonies, film production was controlled by colonial organizations like the Bantu Educational Kinema Experiment, which primarily produced instructional films about hygiene. The French went a step further and passed the Laval Decree in 1934, which banned Africans from making film, lest one of France’s 25 million colonial subjects get it in their head to make films critical of their occupiers.

The 1940s are widely regarded as having been the heyday of Egyptian Cinema. The decade also marked the development of a new sort of ethnographic film after Jean Rouch relocated to what’s now Niger (then part of French West Africa) to work as an engineer. The then-future pioneer of cinema verité began with ethnographic films like 1947’s Au Pays des Mages Noirs. In the 1950s, he began making nouvell vague-informed films that, although still the work of a colonial filmmaker, employed African actors and crews. In fact, Rouch remained in Niger after it gained independence in 1958 and mentored native African filmmakers including Moustapha Alassane, Oumarou Ganda, and Safi Faye.

The 1950s was the decade in which the first real wave of independence swept across Africa, with Libya, Ghana, Morocco, Sudan, and Tunisia all achieving the restoration of sovereignty. Not surprisingly, then, the decade also witnessed a flowering of African cinema. The Société Anonyme Tunisienne de Production et d’Expansion Cinématographique (SATPEC) was founded in the year that followed Tunisia’s independence from France. Two years after Morocco gained independence from France, Mohammed Ousfour (محمد عصفور) directed the first Moroccan feature film, Le fils maudit, in 1958. Egyptian Cinema, already established, saw greater critical recognition for filmmaker Youssef Chahine (يوسف شاهين), whose 1958 Neo-realist film Cairo Station, (باب الحديد), competed at the Berlin International Film Festival (Internationale Filmfestspiele Berlin). At the same time, Egyptian Cinema became the world’s third largest film industry.

In French sub-Saharan Africa, the Laval Decree remained in place until 1960 but filmmakers found ways to critique France’s colonial system. In France, French filmmakers began to make explicitly anti-colonial films. René Vautier made Afrique 50 in 1950. Alain Resnais, Chris Marker, and Ghislain Cloquet made Les statues meurent aussi in 1953. In 1955, Beninese/Senegalese filmmaker Paulin Soumanou Vieyra and others from Le Group Africain du Cinema, which shot Afrique-sur-Seine in Paris — permitted because the Laval Decree didn’t extend to films made within France by African filmmakers — only to African films made within Africa.

In the 1960s, Gamal Abdel Nasser Hussain (جمال عبد الناصر) nationalized Egypt’s cinema, effectively turning it into propaganda factory and thus snuffing out both creativity at home and interest abroad. That said, 1969 also marked the year that Egypt’s Shadi Abdel Salam (شادي عبد السلام) made his debut with Al Fallah al Fasih (الفلاح الفصيح). At the same time, 34 African countries achieved independence in that decade — more so than in any other. Again not coincidentally, another flowering of African cinema took place, this time driven mainly by filmmakers from the newly independent nations of the Sub-Sahara. In 1963, filmmaker Hajji Cagakombe made Somalia’s first feature, Miyi Iyo Magaalo.

Somali director Hajji Cagakombe made Miyi Iyo Magaalo in 1963, Somalia’s first feature film. Senegalese novelist, Ousmane Sembène, turned to film and made his first, Borom Sarret, in 1963. In 1964, Ghana’s first president, Kwame Nkrumah, established the Ghana Film Industry Corporation (GFIC) in Accra. Nigerien filmmaker Oumarou Ganda’s Cabascabo, released in 1968, competed in the Moscow International Film Festival (Моско́вский междунаро́дный кинофестива́ль). That same year, Tashkent, Uzbekistan (then part of the USSR) hosted the Tashkent Festival of African and Asian Cinema, Tashkent. Mauritanian director Med Hondo shot his feature debut, Soleil Ô, over the course of four years, releasing the completed work in 1970. The Festival panafricain du cinéma et de la télévision de Ouagadougou (FESPACO) established in Burkina Faso in 1969. The Fédération Panafricaine des Cinéastes (FEPACI) was formed in 1969 to promote African film industries in terms of production, distribution and exhibition and was inaugurated in 1970.

Egypt’s Saharan neighbors continued to thrive as well. The Carthage Film Festival (أيام قرطاج السينمائية) was inaugrated in Tunisia in 1966. The Mediterranean Film Festival of Morocco (now the Mediterranean Film Festival of Tetouan, Morocco) was inaugurated in Tangier in 1968. Algerian director Mohammed Lakhdar-Hamina‘s (محمد الأخضر حمينة) The Winds of the Aures (ريح الاوراس) (1967) won in the category of “best new film” at the 1967 Cannes Film Festival (Festival international du film).

In October 1969, Argentine filmmakers Fernando Solanas and Octavio Getino, co-founders of the militant Grupo Cine Liberación, published their manifesto, Hacia un tercer cine, which outlined their vision for a cinematic alternative to first cinema (commercial Hollywood cinema and its imitators) and second cinema (individualistic, auteur-driven European cinema), which proved influential for militant Leftist filmmakers in both South America and Africa. African filmmakers including Ousmane Sembène and his Malian peers, Souleymane Cissé and Cheick Oumar Sissoko, among others, studied film at the USSR‘s prestigious Gerasimov Institute of Cinematography (Всероссийский государственный институт кинематографии имени), adapting Russia‘s rich cinematic to create a Russian-influenced by distinctly African film language that relied as much on visuals to communicate their message as dialougue. After all, one a continent where over 2,000 indigenous languages are spoken, how else could an African filmmaker hope to reach a multi-lingual pan-African audience?

It was also in the 1970s, however, that the seeds would be planted for Africa’s most successful commercial film industry, Nollywood. Nollywood films, produced in Nigeria, are in English, a language understood by more than half of Africa’s 1.2 billion inhabitants. Their concerns, arguably, are almost entirely commercial, concerned that is less with artistic expression than entertainment, and their appeal ultimately approved vastly more appealing to the average film-goer than the ambitious art films that characteized the works of Soviet-influenced Francophone Africa. The seeds of Nollywood were planted with the 1972 passage of the Indigenization Decree, which transferred ownership of the country’s roughly 300 cinemas from foreigners to Nigerians. The money that flowed into the country as oil flowed out also contributed immensely to a well-funded cinema increasingly obsessed over time with celebrity and box office returns.

African art filmmakers, deprived of both cinema revenue, government agency backing, and foreign investment struggled as commercial African cinema became more lucrative. By the 1980s, there were popular cinemas flourishing throughout much of Africa. Crowd pleasing musicals called riwaaydo were popular in Somalia. In Uganda, “video jokers” were employed (somewhat like Japan’s silent cinema benshi) to translate dialogue and provide narration — but also (like western “horror hosts”) to interact with and make jokes about the low budget films that appealed to large audiences. The 1980s also saw a rise in home video — proliferated first mainly on VHS tapes and later on VCDs.

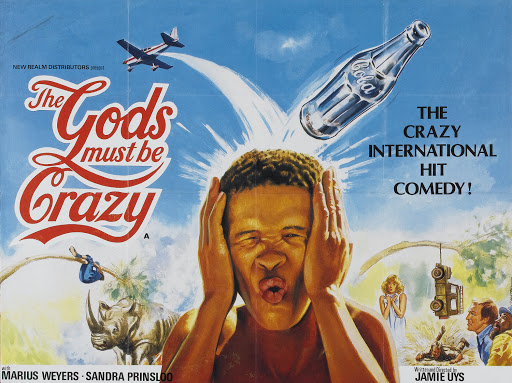

The first globally massive African filmmaker was Jamie Uys‘s 1980 film, The Gods Must Be Crazy. Superficially, the film was a cute throwback to the days of silent film slapstick. The subtext, about a noble savage who worships a bit of garbage casually discarded by a white man as a gift from the apartheid gods, was a bit harder to swallow. The film’s director, unknown until then outside of South Africa, was at best seemingly complacent about apartheid and had built his career making cheerfully non-confrontational films like Animals Are Beautiful People (1974) and Funny People (1976). Uys claimed that he’d communicated with his star, Nǃxau ǂToma, via smoke signals and hadn’t paid him because the unspoiled primitive simply had no concept of money. In reality, Nǃxau ǂToma lived in town, spoke three languages fluently (and passable Afrikaans). The film, made for a budge of roughly 5 million, generated a box office revenue of nearly 100 million.

Nollywood experienced another major boom in the 1990s, spreading in popularity beyond Africa to the Caribbean and African diaspora. At Nollywood’s mid-2000s peak, only India was able to churn out more movies. Nollywood — inspired in name and financial concerns like Hollywood and Bollywood before it — was inspired by similarly nicknamed, including Gollywood, Ghallywood, Hillywood, Kumawood, Riverwood, Swahiliwood, Ugawood, Wakaliwood, &c.

As commercial African cinema flourished in the ’90s, however, one of African cinema’s premier scholar, Nwachukwu Frank Ukadike, began treating African cinema as a whole with the informed critical attention it had, for the most part, been until then denied. His first scholarly book, African Black Cinema (1994), was followed by New discourses of African Cinema (1995, edited by Ukadike), Questioning African Cinema: Conversations with African Filmmakers (2002, edited by Ukadike), African Cinema: Narratives, Perspectives and Poetics (2014), and Critical Approaches to African Cinema Discourse (2014, edited by Ukadike).

The fate of cinemas to crumble in ruin or live on as churches was the same in Africa as in much of the world by the dawn of the 21st century, the majority of Africa’s once vibrant cinemas had gone dark. The 2000s did see the establishment of several film schools, however, including Imagine, built in Ouagadougou by Gaston Kaboré; ECRAN, founded in Togo by Christelle Aquéréburu; and the Blue Nile Film And Television Academy (ብሉ ናይል የፊልም እና የቴሌቪዥን አካዳሚ), established in Ethiopia by cinematographer Abraham Haile Biru. Judged by numbers, however, African cinema was in no apparent danger of extinction and award ceremonies — always concerned at least as much with celebrity pageantry as with actually honoring actual artistry — flourished in number and provided more exuses to roll out a red carpet. By the end of the 2010s, nearly every African nation hosted at least one annual film festival and a growing number are appearing internationally — even if streaming, commercial release, and critical attention remain frustratingly elusive. It’s unclear, yet, what direction African films will take in the 2020s, assuming the COVID-19 pandemic ends and things resume some sense of normalcy. At least until then, many festival will host digital screenings of African films online.

AFRICAN FILM FESTIVALS

- Abuja International Film Festival — Abuja, Nigeria (2004)

- Accra Indie Filmfest (AiF) — Accra, Ghana

- Accra International Film Festival — Accra, Ghana

- Addis International Film Festival — Addis Aba, Ethiopia (2007)

- Africa International Film Festival (AFRIFF) — Calabar, Nigeria (2010)

- Africa World Documentary Film Festival (AWDFF) — San Diego, USA

- Africa in Motion (AiM) — Edinburgh, Scotland (2006)

- African Diaspora International Film Festival (ADIFF) — New York City, USA (1992)

- African Film & Arts Festival (TAFF) — Dallas, USA (2016)

- African Film Festival of Equatorial Guinea — Malabo and Bata, Equitoreal Guinea (2010)

- African Film Festival of Ottawa — Ottowa, Canada (2015)

- African Movie Academy Awards (AMAA) — Nigeria (2005)

- Alexandria International Film Festival –Alexandria, Egypt (1984)

- Amakula International Film Festival — Kampala, Uganda (2004)

- Ananse Cinema International Film Festival — Cape Coast, Ghana

- Angola International Film Festival — Luanda, Angola (2018)

- Architect Africa Film Festival (AAFF) — South Africa (2007)

- Australian Festival of African Film (AFAF) — Brisbane ,Australia (2015)

- Benin City Film Festival — Benin City, Nigeria (2018)

- Black Star International Film Festival (BSIFF) — Ghana (2015)

- Botswana Film Festival — Gaborone, Botswana (2016)

- Cabo Verde International Film Festival — Sal Island, Cape Verde (2010)

- Cairo International Film Festival — Cairo, Egypt (1976)

- Cairo International Women’s Film Festival — Cairo, Egypt (2008)

- Cameroon International Film Festival (CAMIFF) — Buea, Cameroon (2016)

- Carthage Film Festival — Carthage, Tunisia (1966)

- Cascade Festival of African Films — Portland, USA (1991)

- Cinekambiya International Film Festival (CIFF) — Banjul and Brikama, The Gambia (2015)

- Comoros International Film Festival (CIFF) — Moroni, Comoros (2014)

- Congo International Film Festival (CIFF) — Goma, Democratic Republic of Congo (2005)

- Cotonou International Women’s Film Festival (FIFF Cotonou) — Cotonou, Benin (2019)

- Dakar Film Festival — Daka,r Senegal (2006)

- Dockanema — Maputo, Mozambique (2006)

- Durban International Film Festival (DIFF) — Durban, South Africa (1979)

- Eastern Nigeria Film Festival (ENIFF) — Nigieria

- Eko International Film Festival (EKOIFF) — Lagos, Nigeria

- El Gouna Film Festival (مهرجان الجونة السينمائي) — El Gouna, Egypt (2017)

- Encounters South African International Documentary Festival — Cape Town, South Africa (1999)

- Ethiopian International Film Festival (ETHIOIFF) — Addis Aba, Ethiopia (2005)

- Festival International de Cinéma de Kinshasa (FICKIN) — Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo (2015)

- Festival du Film de Masuku — Masuku, Gabon (2013)

- Festival du Films d’Education — Seychelles (2018)

- Galway African Film Festival — Galway, Ireland (2008)

- Global Migration Film Festival — Abidjan, Ivory Coast (2016)

- Guinea Film Festival — Guinea (2014)

- Île Courts International Short Film Festival — Île Courts, Mauritius (2007)

- International Arab Film Festival — Wahran, Algeria (1976)

- International Festival of Cinema and Audiovisual of Burundi — Bujumbura, Burundi (2009)

- International Film Festival of Marrakech — Marrakech, Morocco (2001)

- Kenya International Film Festival — Nairobi, Kenya (2006)

- Kenya International Sports Film Festival (KISFF) — Nairobi, Kenya (2020)

- Legon International Film Festival — Accra, Ghana

- Lesotho Film Festival — Maseru, Lesotho (1999)

- Lights, Camera, Africa! — Lagos, Nigeria (2011)

- Lusaka International Film Festival (LIFF) — Lusaka, Zambia

- Luxor African Film Festival — Luxor, Egypt (2012)

- Madagascar Short Film Festival (2005)

- Malabo International Music & Film Festival — Malabo, Equitoreal Guinea (2019)

- Maputo Cinema Festival — Maputo, Mozambique

- Mawjoudin Queer Film Festival — Tunis, Tunisia (2018)

- Migration Film Festival — Hargeisa, Somaliland (2017)

- New York African Film Festival (NYAFF) — New York City, USA (1993)

- NollywoodWeek Film Festival

- Oran International Arabic Film Festival — Oran, Algeria (2010?)

- Out In Africa South African Gay and Lesbian Film Festival — Cape Town and Johannesburg, South Africa (1994)

- Pan African Film & Arts Festival (PAFF) — Los Angeles, USA (1992)

- Panafrican Film and Television Festival of Ouagadougou (FESPACO) — Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso (1969)

- Pearl International Film Festival — Kampala, Uganda (2011)

- RapidLion – The South African International Film Festival — South Africa

- Reel Peace Film Festival — Monrovia,, Liberia

- Rencontres du Film Court Madagascar — Antananarivo, Madagascar (2006)

- Rock ‘n’ Roll Film Festival Kenya (ROFFEKE) — Kenya (2015)

- Rwanda Film Festival — Kigali, Rwanda (2004)

- Sahara International Film Festival (FiSahara) — Sahrawi refugee camps, Algeria (2003)

- Shungu Namutitima International Film Festival of Zambia (fka International Film Festival of Zambia) (IFFoZ) — Zambia

- Sierra Leone International Film Festival (SLIFF) — Freetown, Sierra Leone (2013)

- Silicon Valley African Film Festival (SVAFF) — San Jose, USA (2010)

- Silwerskerm FilmFees — Camps Bay, South Africa (2010)

- Slum Film Festival — Nairobi, Kenya (2011)

- South African Independent Film Festival — South Africa

- Sudan Independent Film Festival — Khartoum, Sudan (2014)

- Sydney South African Film Festival (SSAFF) — Sydney, Australia (2019)

- São Tomé and Príncipe International Film Festival — São Tomé and Príncipe (2011)

- South African Film and Television Awards — Sun City, South Africa (2006)

- Toronto South African Film Festival — Toronto, Canada (2014)

- Transforming Stories International Christian Film Festival (TSICFF) — Johannesburg, South Africa (2010)

- Uganda Film Festival — Kampala, Uganda (2013)

- Vancouver South African Film Festival (VSAFF) — Vancouver, USA (2010)

- Zambia Short Fest — Zambia

- Zanzibar International Film Festival (ZIFF) — Zanzibar, Tanzania (1997)

- Zimbabwe International Film Festival (ZIFF) — Harare, Zimbabwe (1997)

AFRICAN FILMMAKERS

Whilst recognizing that most films are obviously the result of a collaboration between cast and crew, I do believe that the director is generally the primary creative author of a film and so — with respect to all the African cinematographers, editors, screenwriters, producers, actors, &c — I’m here only listing African directors — in most cases with given name followed by family name.

A

Ababacar Samb-Makharam, Abakar Chene Massar, Abdelkader Lagtaâ (عبد القادر لقطع), Abdella Zarok (aka Abdellah Rezzoug — عبد الله الزروق), Abdellatif Kechiche (عبد اللطيف كشيش), Abderrahmane Sissako, Abdi Ali Geedi, Abdisalam Aato, Abdulkadir Ahmed Said (Cabdulkaadir Axmed Saciid), Abdurrahman Yusuf Cartan, Abel Rakotozanany, Adama Drabo, Adanech Adamssu, Adekunle “Nodash” Adejuyigbe, Adze Ugah, Ahmed Boulane (أحمد بولان), Ahmed El Maanouni (أحمد المعنوني), Ahmed Lallem, Ahmed Rachedi (أحمد راشدي), Akin Omotoso, Akintola Akin-Lewis, Alassane Diago, Alastair Orr, Albert Likeke Mongita, Albert Samama Chikly (ألبير شمامة شيكلي), Albert Wandago, Albie Venter, Alex Wasponga, Alexander Abela, Alexander Konstantaras, Ali Benjelloun, Ali Said Hassan (Cali Saciid Xasan), Alidou Badini, Aliki Saragas, Alphonse Beni, Amar Laskri (عمار العسكري), Andre Velts, Andrew Dosunmu, Andrey Samouté Diarra, Andriamanisa Radoniaina, André Odendaal, Andy Chukwu, Anisia Uzeyman, Angelo Kinyua, Angus Gibson, Anne-Laure Folly, Anthony Silverston, Anthony Wilson, António Ole, Apolline Traoré, Arcade Assogba, Armand Balima, Arthur Leslie Bennett, Ashraf Ssemwogerere, Augustin Roch Taoko, and Azza Cheikh Malainine

B

Bacary Bax, Bakary Sonko, Balufu Bakupa-Kanyinda, Bassek Ba Kobhio, Beer Adriaanse, Ben Diogaye Bèye, Bereket Werede, Berni Goldblat, Biko Nyongesa, Biyi Bandele, Bob Nyanja, Bob-Manuel Obidimma Udokwu, Bolaji Amusan, Brett Michael Innes, Brian Webber, Bridget Pickering, Bromley Cawood, Brutus Sirucha, Bryony Roughton, and Byron Davis

C

C. Francis Coley, C. J. Obasi, Cajetan Boy, Catherine Stewart, Cecil Moller, Charles Novia, Charles Shemu Joyah, Charlie Vundla, Cheick Fantamady Camara, Cheick Oumar Sissoko, Chet Anekwe, Chico Ejiro (né Chico Maziakpono), Chike C. Nwoffiah, Chineze Anyaene, Chris Obi-Rapu, Christa Eka, Christelle Aquereburu, Christiaan Olwagen, Christine Bala, Christopher Akintola Ogungbe, Claude Cadiou, Claude Gnakouri, Corné Van Rooyen, Craig Freimond, Cumar Cabdalla, and Cynthia Butare

D

D. Bruce Mcfarlane, Daan Retief, Dalila Ennadre (دليلة الندري), Dani Kouyaté, Daniel Ademinokan, Daniel Kamwa, Daoud Aoulad-Syad, Daouda Coulibaly, Darrell James Roodt, Daryne Joshua, David Bensusan, David Forbes, David Lister, David Millin, David Randriamanana, David Sikhosana, David Wicht, David “Tosh” Gitonga, Denis Scully, Desiré Ecaré, Desmond Oluwashola Elliot, Dia Moukouri, Dick Cruikshanks, Dickson Iroegbu, Didier Aufort, Didier Florent Ouénangaré, Dilman Dila, Diony Kempen, Dirk De Villiers, Djibril Diop Mambéty, Djimon Hounsou, Djingarey Maïga, Djo Tunda Wa Munga, Dolapo ‘Lowladee’ Adeleke, Donovan Marsh, Dorris Haron Kasco, Driss Mrini (إدريس المريني), and Dyana Gaye

E

Edouard Sailly, Ejike Asiegbu, Elaine Proctor, Elmo De Witt, Emamode Edosio, Emem Isong, Emil Nofal, Emmanuel Sanon-Doba, Eric Aghimien, Erin Offer, Ernest Nkosi, Etienne Fourie, Etienne Kallos, Eubulus Timothy, Evelyn Kahunga, and Ezzel Dine Zulficar (عزالدين ذو الفقار)

F

Fabrice Maminirina Razafindralambo, Fadika Kramo-Laciné, Falaba Issa Traoré, Fanta Régina Nacro, Faouzi Bensaïdi (فوزي بنسعيدي), Farida Benlyazid (فريدة بليزيد), Fatoumata Coulibaly, Femi Odugbemi, Ferdinand Kanza, Férid Boughedir (فريد بوغدير), Flora Gomes, Francisco Henriques, François Sourou Okioh, Francois Swart, François Verster, Frank Fiifi Gharbin, Frank Rajah Arase, Frans Nel, Franz Marx, Fred Amata, Fuad Abdulaziz, and Funsho Adeolu

G

G. Borg, Gaston Kaboré, Gatta Abdourahamane, George Keita, Gilbert Baramna, Godwin Mawuru, Guenny K. Pires, Guy Bomanyama-Zandu, Gavin Hood, Genevieve Nnaji, Gerrit Schoonhoven, Gersh Kgamedi, Gloria Olusola Bamiloye, and Gray Hofmeyr

H

Hakim Belabbes, Hakim Noury (حكيم نوري), Haile Gerima, Hamid Bénani (حميد بناني), Hani Khalifa (هاني خليفة), Hanneke Schutte, Harold Hölscher, Hassan Benjelloun (حسن بنجلون), Hassan Legzouli, Hassan Ramzi, Hawa Essuman, Hendrik Cronje, Henok Ayele (ሔኖክ አየለ), Henri Duparc, Henry Antoun Barakat (هنري أنطون بركات), Hermon Hailay, Hicham Ayouch (هشام عيوش), Hisham Lasri (هشام العسري), Hubert Ogunde, Hajji Cagakombe (aka Hadj Mohamed Giumale), Hanneke Schutte, Hassan Mohamed Osman, Helena Nogueira, Henk Pretorius, Howard James Fyvie, and Hussein Mabrouk

I

Ibrahim Ceesay, Idrissa Ouédraogo, Idrissou Mora-Kpai, Ingolo Wa Keya, Inoussa Ousséïni, Ishaya Bako, Ismaël Ferroukhi, Issa Serge Coelo, Issiaka Konaté, Ivan Botha, Ian Gabriel, Idil Ibrahim, Idriss Hassan Dirie, Ikechukwu Onyeka, Isaac Godfrey Geoffrey Nabwana, Ivan Hall, and Izu Ojukwu

J

Jab Adu, Jaco Bouwer, Jaco Smit, Jacques Oppenheim, Jacques Trabi, Jahmil X. T. Qubeka, James H. Murray, Jan Scholtz, Jane Murago-Munene, Jane Thandi Lipman, Jani Dhere, Jann Turner, Jason Xenopoulos, Jawad Rhalib, Jayan Moodley, Jayant Maru, Jaymie Uys (né Jacobus Johannes Uys), Jean Marie Tenu, Jean Odoutan, Jean Van De Velde, Jean-Michel Kibushi Ndjate Wooto, Jean-Pierre Bekolo, Jean-Claude Rahaga, Jean-Louis Koula, Jean-Paul Ngassa, Jean-Pierre Dikongue Pipa, Jenna Cato Bass, Jeremy Crutchley, Jerome Pikwane, Jeta Amata, Jilali Ferhati (الجيلالي فرحاتي), Jiva Eric Razafindralambo, João Ribeiro, Joe Stewardson, Joel Haikali, Joël Tchédré, Johan Cronje, Johannes Ferdinand Van Zyl, John Barker, John Trengove, Johnny Barbuzano, Joke Silva, Josef Kumbela, Joseph Akouissone, Joseph Albrecht, Joshua Rous, Josiah Kibira, José Fonseca E Costa (José Manuel Carvalheiro Da Fonseca E Costa), Joyce Mhango-Chavula, Jozua Malherbe, Joël Karekezi, Judy Kibinge, Judy Naidoo, Julia Jansch, Juma Idrisse, and Jürgen Schadeberg

K

Kagiso Lediga, Kaitlyn Summerill, Kaizer Matsumunyane, Kamal Selim (كمال سليم), Karabani, Karin Slater, Kasem Hwel, Katinka Heyns, Katy Léna N’diaye, Kemi Adetiba, Kenneth Gyang, Khady Sylla, Khalo Matabane, Kiluanje Liberdade, King Ampaw, Kingsley Ogoro, Kitia Touré, Kivu Ruhorahoza, Kollo Daniel Sanou, Konstandino Kalarytis, Koos Roets, Kofi Ofosu-Yeboah, Kozoloa Yéo, Krischka Stoffels, Kunle Afolayan, and Kwaw Ansah

L

Lacina Diaby, Laïla Marrakchi (ليلى المراكشي), Laitan Faranpojo, Lara Sousa, Laza, Léandre-Alain Baker, Leïla Kilani (لَيْلَى كيلاني), Leli Maki, Lemohang Jeremiah Mosese, Léonce Ngabo, Léonie Yangba Zowe, Lineo Sekeleoane, Lova Nantenaina, Luck Razanajaona, Ladi Ladebo, Lancelot Oduwa Imasuen, Lansana Mansaray, Laszlo Bene, Leon Schuster, Liban Barre, Lionel Friedberg, Lonzo Nzekwe, Louis Knobel, Lula Ali Ismaïl, and Lwazi Mvusi

Un homme qui crie (dir. Mahamat-Saleh Haroun, 2010)

M

M. Pounie, Maganthrie Pillay, Mahama Johnson Traoré, Mahamane Bakabé, Mahamat-Saleh Haroun (محمد الصالح هارون), Mahmood Ali-Balogun, Mak ‘Kusare, Mama Keïta, Mamadou Djim Kol, Mamihasina Raminosoa, Mandla Walter Dube, Manie Van Rensburg, Mankany Haminiaina Ratovoarivony, Manouchka Kelly, Mansour Sora Wade, Maria João Ganga, Mariama Hima, Marie Clémentine Dusabejambo, Marie-Clémence Andriamonta Paes, Mário Bastos, Mark Dornford-May, Martin Mhando, Marwan Hamed (مروان حامد), Maryam Touzani (مريم التوزاني), Matt Bish, Matthys Boshoff, Maynard Kraak, Mayowa Oluyeba, Mbongeni Ngema, Med Hondo, Meg Rickards, Mehdi Charef (ميهدى تشاريف), Merzak Allouache (مرزاق علواش), Mesfin Getachew (መስፍን ጌታቸው), Michael Matthews, Michael Raeburn, Michael J. Rix, Michael Wright, Michelle Bello, Michelle Medina, Mickey Fonseca, Mildred Okwo, Missa Hébié, Mo Ali (Maxamed Cali), Mohamed Abderrahman Tazi (محمد عبد الرحمن التازي), Mohamed Camara, Mohamed Fiqi, Mohamed Ismail, Mohammed Goma Ali, Mohammed Lakhdar-Hamina (محمد الأخضر حمينة), Mohammed Ousfour (محمد عصفور), Mohiedin Khalief Abdi, Molatelo Mainetje-Bossman, Morné Du Toit, Moses Olaya Adejumo, Moufida Tlati (مفيدة التلاتلي), Moumen Smihi (مومن السميحي), Moussa Dosso, Moussa Ouane, Moussa Sène Absa, Moussa Touré, Moustapha Alassane, Moustapha Dao, Moustapha Diop, Mustapha Derkaoui (مصطفى الدرقاوي), Muxiyadiin Qaliif Cabdi, and Mwezé Ngangura

District 9 (dir. Neill Blomkamp, 2009, South Africa)

N

Nabil Ayouch (نبيل عيوش), Nacer Khemir (ناصر خمير), Naceur Ktari (الناصر القطاري), Nadir Bouhmouch (نادر بوحموش), Narjiss Nejjar (نرجس النجار), Nathan Collett, Neil Hetherington, Néjia Ben Mabrouk (نجية بن مبروك), Nejib Belkadhi (نجيب بلقاضي), Nicola Hanekom, Njeri Karago, Njue Kevin, Norman Maake, Nosipho Dumisa-Ngoasheng, Nour-Eddine Lakhmari (نور الدين), Nouri Bouzid (نوري بوزيد), Nabiil Hassan Nur, Ndave David Njoku, Neal Sundstrom, Neill Blomkamp, Newton I. Aduaka, Nicholas Costaras, Niji Akanni, Niyi Akinmolayan, Nonso Diobi, and Ntshavheni Wa Luruli

La Noire de… (dir. Ousmane Sembène, 1966, Senegal)

O

Obi Emelonye, Ola Balogun, Olatunde Osunsanmi, Oliver Hermanus, Oliver Rodger, Oliver Schmitz, Ondjaki Liberdade, Orlando Fortunato de Oliveira, Orlando Mabasso Jr., Oshosheni Hiveluah, Oumarou Ganda, Ousmane Ilbo Mahamane, Ousmane Sembène, and Owell A. Brown

P

Pascal Abikanlou, Paul Zoumbara, Paulin Soumanou Vieyra, Perivi Katjavivi, Petna Ndaliko, Philippe Lacôte, Philippe Raberojo, Pascal Amanfo, Pascal Atuma, Patrick Mynhardt, Pierre De Wet, and Prince Eke

Q

R

Rabii El Jawhari (ربيع الجوهري), Rahmatou Keïta, Raoul Peck, Rasselas Lakew, Ravneet “Sippy” Chadha, Raymond Rajaonarivelo, Regardt van den Bergh, René Bernard Yonli, Revel Fox, Richard Daneel, Richard E. Grant, Richard Gau, Richard Pakleppa, Richard Quartey, Richard Stanley, Robert Davies, Roberta Durrant, Robin Benger, Robinson Christian Englestoft Nissen, Roger Gnoan M’bala, Roger Hawkins, Rogério Manjate, Rogers Ofime, Ronnie Isaacs, Ross Devenish, Ross Kettle, Rungano Nyoni, and Ruy Duarte De Carvalho

Yeelen (dir. Souleymane Cissé, 1987, Mali)

S

S. Pierre Yameogo, Saad Chraibi (سعد الشرايبي), Saalim Bade, Safi Faye, Said Khallaf (سعيد خلاف), Said Salah Ahmed (Saciid Saalax Axmed), Saint Obi, Salif Traoré, Salmon De Jager (aka Sallas de Jager), Sam Dede, Samuel Ishimwe, Samuel K. Nkansah, Sana Na N’hada, Sanvi Alfred Panou, Sao Gamba, Sara Blecher, Sarah Maldoror, Scottnes L. Smith, Sean Else, Sékou Traoré, Selma Baccar (سلمى بكار), Semagngeta Aychiluhem, Serge Bilé, Shadi Abdel Salam (شادي عبد السلام), Shan George, Shane Vermooten, Sharad Patel, Shyaka Kagamé, Sias Odendal, Sibs Shongwe-La Mer, Sidiki Bakaba, Sikiru Adesina, Simiyu Barasa, Simon Bingo, Simon Makwela, Simon Mukali, Simon Wilkie, Sitraka Randriamahaly, Solo Ignace Randrasana, Solomon Alemu Feleke (ሰለሞን አለሙ), Sorious Samura, Sou Jacob, Souad El-Bouhati, Souheil Ben-Barka, Souleymane Cissé, Stefan Nieuwoudt, Stephanie Okereke Linus, Stephina Zwane, Steve T. Ayeny, Steven Kanumba, Steven Silver, Stuart Pringle, Sue Maluwa-Bruce, Sydney Taivavashe, and Sylvestre Amoussou

T

Tade Ogidan,Tawanda Gunda Mupengo, Teboho Mahlatsi, Teco Benson, Thabang Moleya, Thabo Mashiala, Thérèse Sita-Bella, Tim Huebschle, Timité Bassori, Timothy Greene, Tobie Cronjé, Toky Randriamahazosoa, Tolulope Ajayi, Tommie Meyer, Tope Oshin, Toyin Abraham, Trevor Clarence, Tsitsi Dangarembga, and Tunde Kelani

U

Uche Jombo, Uga Carlini, and Usama Mukwaya

V

Valério Truffa, Vedat Örfi Bengü, Victor Viyuoh, Vincent Cox, Vincent Kigosi, and Vusi Magubane

W

Wale Adenuga, Wanjiru Kinyanjui, Wanuri Kahiu, Wéré Wéré Liking, William Akuffo, Willem Oelofsen, and Wole Oguntokun

X

Cairo Station (dir. Youssef Chahine, 1958, Egypt)

Y

Yared Shumete, Yared Zeleke, Yewande Adekoya, Yohannes “Jani” Baye, and Youssef Chahine (يوسف شاهين)

Z

Zack Orji, Zaheer Goodman-Bhyat, Zane Meas, Zeka Laplaine (aka José Laplaine), Zézé Gamboa, Zina Saro-Wiwa, and Zola Maseko

Support Eric Brightwell on Patreon

Eric Brightwell is an adventurer, essayist, rambler, explorer, cartographer, and guerrilla gardener who is always seeking paid writing, speaking, traveling, and art opportunities. He is not interested in generating advertorials, cranking out clickbait, or laboring away in a listicle mill “for exposure.”

Brightwell has written for Angels Walk LA, Amoeblog, Boom: A Journal of California, diaCRITICS, Hidden Los Angeles, and KCET Departures. His art has been featured by the American Institute of Architects, the Architecture & Design Museum, the Craft Contemporary, Form Follows Function, Los Angeles County Store, the book Sidewalking, Skid Row Housing Trust, and 1650 Gallery. Brightwell has been featured as subject in The Los Angeles Times, Huffington Post, Los Angeles Magazine, LAist, CurbedLA, Eastsider LA, Boing Boing, Los Angeles, I’m Yours, and on Notebook on Cities and Culture. He has been a guest speaker on KCRW‘s Which Way, LA?, at Emerson College, and the University of Southern California.

Brightwell is currently writing a book about Los Angeles and you can follow him on Ameba, Duolingo, Facebook, Goodreads, Instagram, Mubi, and Twitter.