ALIGNING EXPECTATION WITH POSSIBILITY

Why is the world at large so often “surprised” when the materially impossible doesn’t happen?

In economics, the consensus line – a narrative shared by government, business and, for the most part, the general public – is that the economy will carry on growing as we shift from climate-harming fossil fuels to cleaner alternatives such as wind and solar power. This process, boosted by advances in technology, will increase our leisure time, and give us more money to spend on discretionary (non-essential) products and services.

In reality, none of this can happen, yet we keep being “surprised” when it doesn’t.

Renewable energy cannot replicate all of the economic value hitherto sourced from oil, natural gas and coal, and the supposedly “green” credentials of renewables are, to put it mildly, highly debatable. EVs can’t replace all of the world’s ICE-powered vehicles on a like-for-like basis.

As top-line prosperity decreases, and the costs of energy-intensive necessities carry on rising, the affordability of discretionary products and services will decline. A string of sectors and activities widely regarded as highly growth-capable are, in reality, heading into relentless contraction.

This same process of affordability compression is going to undermine the ability of the household and corporate sectors to service, let alone honour, their enormous debt and quasi-debt obligations.

In short, the much-cherished consensus view of the economic future is founded on a series of material impossibilities.

Accordingly, anticipated “growth” in discretionary sectors like travel, leisure, hospitality, the media and entertainment won’t happen, and these sectors will, instead, start to contract. The same thing will happen to “tech”, undermining faith in the concept of inexhaustible, profitable growth driven by the relentless advance of innovation.

Property prices will fall as affordability is compressed, and the authorities will come under increasing pressure to cut rates and resume the creation (“printing”) of money. There will be another “banking crisis”, except that, this time around, systemic risk won’t emerge first in banks themselves, but from within parts of the NBFI sector (the non-bank financial intermediaries known colloquially as “shadow banks”).

Meanwhile, the authorities will come under ever-increasing pressure to explain why people are getting poorer in supposedly “growing” economies (and good luck with that one).

These considerations take us into the purposes of projection. If you’re convinced that economic catastrophe looms, there may seem little point in forecasting disparities in performance.

If, though, you believe that we might muddle through – that ‘things are never as good as we hope, or as bad as we fear’– then there’s much to be gained by calling out the distinctions between consensus expectation and material possibility, and using these discrepancies to frame our choices.

As consumers, voters, employers, employees and investors, times might be hard, but there’s little merit in making things worse than they need to be by exposing ourselves to the worst disappointments that are looming for the consensus.

How, then, can we draw these distinctions between the generally-expected and the materially-possible?

‘Man bites dog’

The unexpected is newsworthy, whilst the widely anticipated usually isn’t. Snow in Wales during December barely makes the news, but snow in July would be the stuff of headlines.

The headline article in the Financial Times on 3rd April referenced declining sales of electric vehicles by Tesla and Chinese competitor BYD. These falling sales, said the FT, had “stoke[d] scepticism over speed of electric shift”, raising “fears for long-term growth” in the EV sector.

Two days later, the Times ran a similar story about EVs losing market share in the United Kingdom.

This is newsworthy because it runs contrary to consensus expectations, which are that sales of EVs will continue to grow to a point at which all cars and lorries powered by internal combustion engines will have been replaced.

My first reaction to this story, and perhaps yours too, was to wonder why anyone was surprised by this at all. We have long known that replacing all, or even most, of the world’s two billion cars and commercial vehicles with battery-powered alternatives has never been within the bounds of practical possibility.

It’s more than doubtful that we have the raw materials to produce this many EVs and, even if we did, we don’t, and won’t, have the energy required to access and process these materials, or to power an EV fleet of this size. EVs have only advanced as far as they have because of generous government incentives, and these can’t be sustained in perpetuity.

The consensus narrative about EVs is, of course, a branch of the wider assumption that we can replace all of the energy value hitherto sourced from fossil fuels with cleaner alternatives from renewable energy sources, principally wind and solar power, thereby averting environmental disaster at no cost to standards of living.

This, again, isn’t feasible. Other considerations aside, the far lesser energy density of renewables alone makes this impossible.

Technology can’t get us past these material obstacles, because technology can’t create raw materials that don’t exist, or repeal the laws of thermodynamics that determine the characteristics of different sources of energy.

To assume otherwise is to accede to a collective hubris which contends that human ingenuity can make us masters of the universe when, in reality, the potential scope of technological advance is strictly circumscribed, by finite material resources and by the laws of physics.

Rather than pursue the theme of energy impossibility – that renewables aren’t a like-for-like replacement for oil, natural gas and coal, and that neither renewables nor EVs deserve their supposedly hyper-positive environmental credentials – my thoughts turned in another direction.

How many other non-surprising “surprises” are we going to encounter as the economy inflects from growth into contraction, and as the costs of energy-intensive necessities carry on rising?

Why, in essence, is the world at large so “surprised” when the impossible doesn’t happen?

The basis of myth

According to conventional economics, we live in a world of infinite possibility, and we owe it all to the human contrivance of money.

No material shortage need ever put the brakes on growth. If something is in short supply, its price will rise. As well as discouraging consumption, price rises incentivize producers to bring new supply to the market, and encourage both substitution (where consumers switch to buying something else instead) and innovation (where we find new ways of supplying or substituting for the product in question).

This theory can sometimes work in practice, in markets for things like coffee. If the price of coffee rises, some consumers will buy tea instead. High prices encourage suppliers of coffee to increase planting and harvesting, perhaps growing coffee on land that previously grew something else. We might find improved methods of growing and processing coffee beans.

These, though – whisper it who dares – are mechanisms with limited reach.

Another way to put this is that this money-only economic theory might well have worked in an agrarian society of the kind that was universal in 1776, when Adam Smith penned The Wealth of Nations, the founding treatise of classical economics. Smith can’t be criticised for not knowing what would happen after another Scot, James Watt, gave society the first truly efficient machine for converting heat into work.

Ironically, this also happened in 1776.

Both the agrarian and the industrial economies are energy systems, as all economies are. But the similarity ends there. In agrarian economies, energy is sourced from human and animal labour, and from the nutritional energy which makes this labour possible. Even supplemented by some rudimentary wind and water power, this system was never going to expand the global population ten-fold, or create severe environmental and ecological hazard.

Unlike the principles of classical economic theory, the economy itself has moved on since 1776. The vast majority of the energy used by the system now comes, not from human or animal labour, but from oil, natural gas and coal, which continue to account for four-fifths of primary energy supply. Hydroelectric and geothermal power make useful but limited contributions, as does nuclear, though the latter has never – thus far – lived up to some of the more outlandish promises made on its behalf when we first harnessed “the mighty atom”.

Energy, though, is fundamentally different from commodities like coffee and tea. If coffee is too expensive for economies or consumers to buy, they are no worse off for not having it – they simply spend their money on something else.

But a household or an economy deprived of energy is materially poorer, because everything that we produce or consume is a function of the energy available to the system.

In short, the principles applicable to the working of an agrarian economy don’t work in an industrial society, because they don’t apply to energy.

Anyone who understands this fundamental difference possesses the ace-in-the-hole for out-forecasting those by whom this critical distinction hasn’t been recognised. This takes us into the dynamics of material economic prosperity.

An understanding of process

Essentially, the industrial economy works by using energy to convert natural resources into material products and services. This is a two-part equation, with the production process operating in tandem with the dissipative conversion of energy from dense into diffuse forms. This productive-dissipative process becomes a dissipative-landfill system when we choose to accelerate the rate at which products are relinquished and replaced.

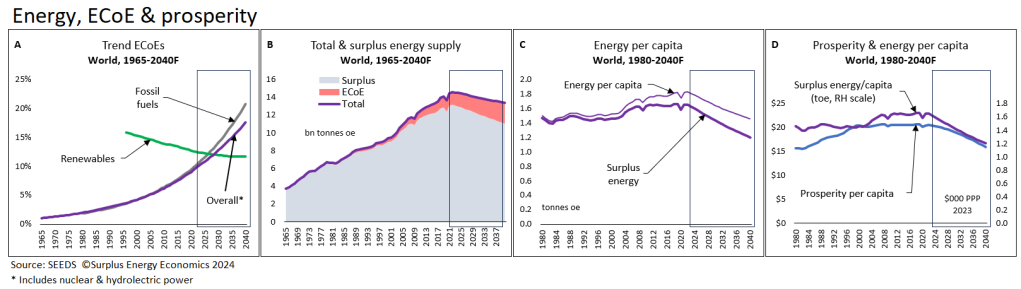

Importantly, if we switch to energy inputs of lesser density, the dissipative process is truncated, the parallel productive process is correspondingly shortened, and the economy gets smaller. This, ultimately, is why renewables cannot replace all of the economic value hitherto sourced from oil, gas and coal.

The friction drag on this dynamic is the cost of energy, a cost which isn’t financial (because we can always create money), but material. Because putting energy to use requires the creation, operation, maintenance and replacement of a material infrastructure – and nothing material can be created or operated without energy – the supply of energy is a process in which we have to use energy in order to get energy.

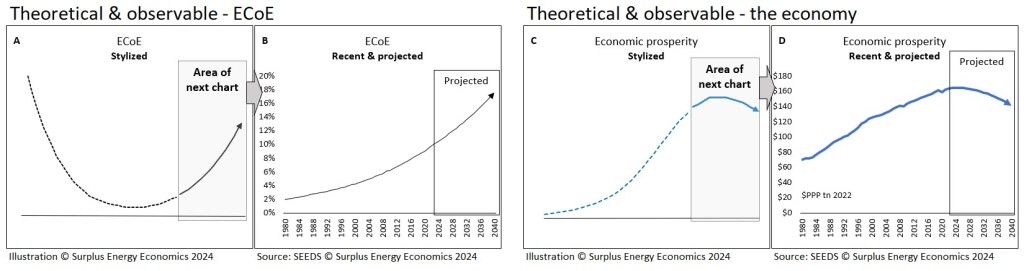

Put another way, “whenever energy is accessed for our use, some of this energy is always consumed in the access process”. This “consumed in access” component is known in Surplus Energy Economics as the Energy Cost of Energy, abbreviated ECoE.

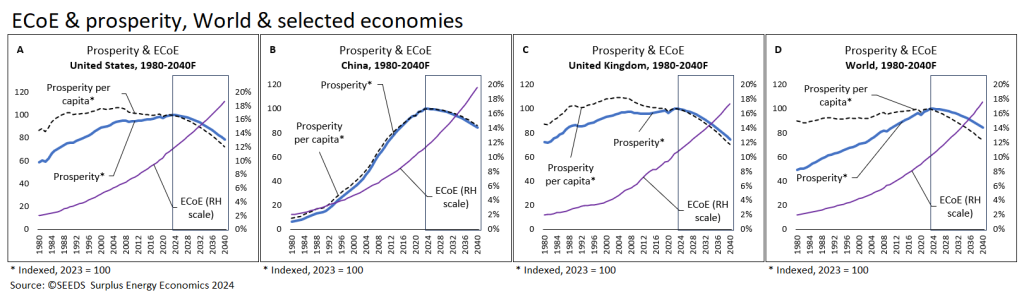

If ECoEs fall, any given quantity of energy yields a larger quantity of ex-cost economic value. If ECoEs rise, this material economic value decreases. Prosperity is defined in SEE as the financial corollary of the surplus (ex-ECoE) energy available to the system.

Money plays a humbler role in the economy than that claimed for it by classical economics. Money can’t overcome physical limits, convert natural resource scarcity into surplus, or power infinite economic growth on a finite planet.

Rather, money functions as a medium of exchange, meaning that the owner of money has an exercisable claim on the output of the material economy.

This is fine so long as monetary claims are matched by corresponding quantities of material products and services available for exchange. Prices, as the monetary values ascribed to material products and services, act as the interface between the material economy and its monetary proxy, and comparative analysis of these two economies is by far the best way of working out what inflation really is.

This is why SEEDS uses its own conception of systemic inflation, RRCI (the Realised Rate of Comprehensive Inflation).

The application of principle

The recognition of the economy as an energy system more or less compels us to adopt the conceptual necessity of two economies. One of these is the “real economy” of material products and services, and the other is the parallel “financial economy” of money, transactions and credit.

From this process, certain observations about our current predicament and future prospects can be reached, and most of them run counter to the consensus narrative.

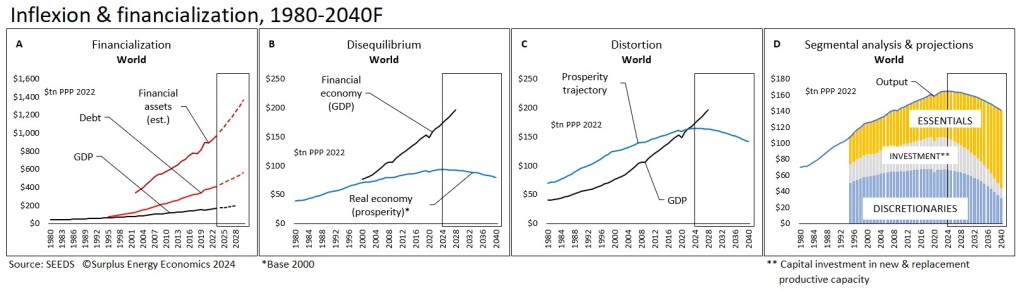

First, the economy has started to shrink, because ECoEs are rising at a far more rapid pace than can conceivably be matched, let alone overtaken, by increases in the supply of total (pre-ECoE) energy – indeed, the likelihood now is that aggregate energy supply will decrease, because renewables are likely to be added at a rate which falls short of the pace at which fossil fuel availability decreases.

There is most unlikely to be any improvement in the rate of conversion which governs the amount of pre-cost economic output generated from each unit of energy available to the system. Accordingly, output will decrease, whilst the difference between output and prosperity will widen as a result of rising ECoEs.

The energy-intensive nature of so many necessities dictates that the costs of essentials will carry on rising. Investment in new and replacement productive capacity can be expected to decrease, for two main reasons. First, opportunities for profitable investment are contracting.

Second, a little-noted but critical trend has undermined the process of investment itself.

Historically, investors’ returns on their capital came in the form of cash dividends and coupons, supplemented by capital appreciation driven by rises in anticipated forward income streams.

Now, though, yield – the rate of cash returns – has been very severely depressed, and investors’ returns come mainly in the paper form of capital gains, and these, in aggregate, can never be monetised. Once the “everything bubble” in asset prices bursts, returns on invested capital will fall back to the (very low) levels provided by yield alone.

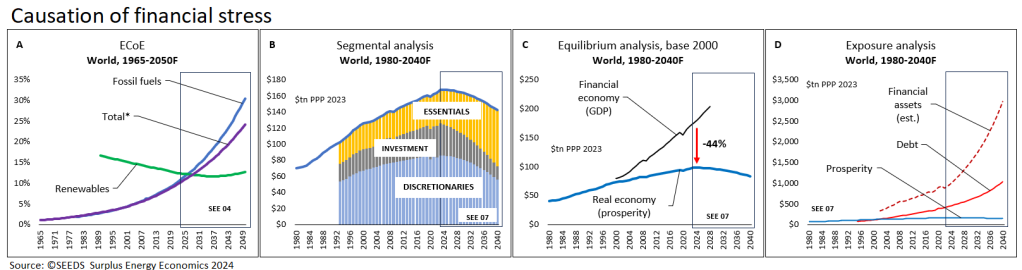

This trend needs to be seen in the context of rising financial stress and worsening exposure. Stress can be measured by comparing movements over time in the material and monetary economies, remembering that a tendency towards equilibrium is inherent in the claims relationship between the two economies.

Quantitative exposure has, of course, increased dramatically, with both debt and broader quasi-debt outgrowing the economy, even when the latter is calibrated as GDP, a measure artificially-inflated by the credit effect on transactional activity.

In essence, a radical correction in the relationship between financial stock and material economic prosperity has been hard-wired into the system.

Knowing this, however, makes it no less important that we understand that discretionary sectors are going to be the main victims of a process of leveraged compression, as the costs of essentials rise at the same time as the material economy itself is contracting.

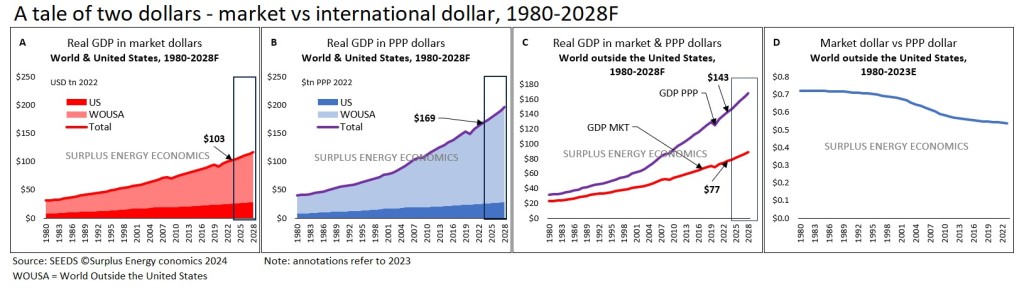

Fig. 1