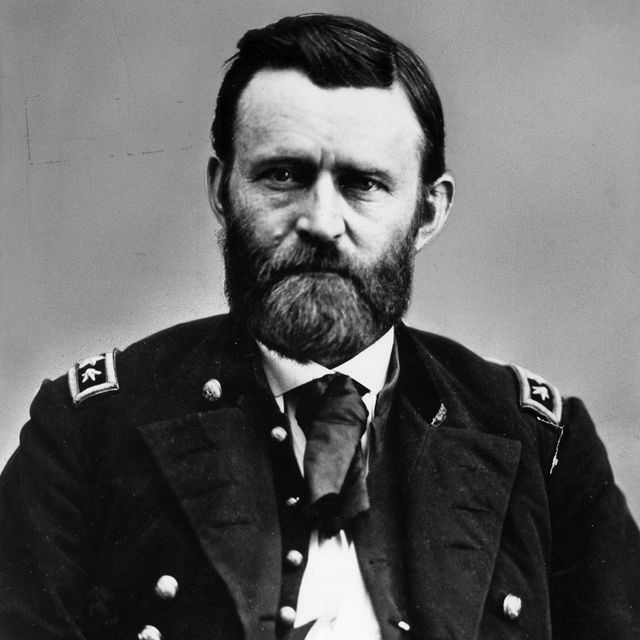

(1822-1885)

Who Was Ulysses S. Grant?

Ulysses S. Grant was entrusted with the command of all U.S. armies in 1864 and relentlessly pursued the enemy during the Civil War. In 1869, at age 46, Grant became the youngest president in U.S. history. Though Grant was highly scrupulous, his administration was tainted with scandal. After leaving the presidency, he commissioned Mark Twain to publish his best-selling memoirs.

Quick Facts

FULL NAME: Hiram Ulysses Grant

BORN: April 27, 1822

DIED: July 23, 1885

BIRTHPLACE: Point Pleasant, Ohio

SPOUSE: Julia Dent (1848-1885)

CHILDREN: Frederick, Ulysses Jr., Ellen, Jesse

ASTROLOGICAL SIGN: Taurus

Early Years

Grant was born Hiram Ulysses Grant on April 27, 1822, in Point Pleasant, Ohio, near the mouth of the Big Indian Creek at the Ohio River. He was the first son of Jesse Root Grant, a tanner and businessman, and Hannah Simpson Grant. A year after Grant was born, his family moved to Georgetown, Ohio, and had what he described as an "uneventful" childhood. He did, however, show great aptitude as a horseman in his youth.Grant was not a standout in his youth. Shy and reserved, he took after his mother rather than his outgoing father. He hated the idea of working in his father's tannery business—a fact that his father begrudgingly acknowledged. When Grant was 17, his father arranged for him to enter the United States Military Academy at West Point. Grant didn't excel at West Point, earning average grades and receiving several demerits for slovenly dress and tardiness, and ultimately decided that the academy "had no charms" for him. He did well in mathematics and geology and excelled in horsemanship. In 1843, he graduated 21st out of 39 and was glad to be out. He planned to resign from the military after he served his mandatory four years of duty.

Origins of “U.S.” Grant Nickname

His famous moniker, "U.S. Grant," came after he joined the military.

Grant was born Hiram Ulysses and went by Ulysses as a child. However, when he arrived at West Point, he expected to be listed on the sheet of incoming cadets by his birth name and was surprised to learn there was no H.U. Grant on the roll call but a U.S. Grant. The clerical error had been made by the Ohio Congressman who nominated Grant to West Point, who may have accidentally combined Grant’s middle name with his mother’s maiden name, Simpson.

Not wanting to make a fuss as a new arrival at West Point and risk being rejected, Grant agreed to go along with the name change but later joked that the “S” in his name stood for nothing. Fellow soldiers at West Point called the newly christened U.S. Grant “Sam,” a shortened version of Uncle Sam.

Wife and Family

After graduation from West Point, Lieutenant Grant was stationed in St. Louis, Missouri, where he met his future wife, Julia Dent, the sister of Grant’s West Point roommate. Grant proposed marriage in 1844, but both families were unhappy with the match. Grant’s abolitionist father disapproved of the Dents owning enslaved people, and Julia’s father considered Grant a low-paid soldier with little prospect of financial success.

The couple initially kept their engagement secret, but Grant eventually won over Julia’s father, and the pair received permission to marry. Their plans were interrupted by the outbreak of the Mexican-American War, which led to a nearly four-year separation. They finally wed in 1848 and would have four children: Frederick (1850), Ulysses Jr., known as “Buck" (1852), Ellen, known as “Nellie” (1855), and Jesse (1858).

The Grants were a close couple, and the frequent separations early in the marriage due to Grant’s military postings affected them both, particularly Ulysses, whose loneliness and isolation from his family likely exacerbated his drinking. During Grant’s Civil War service, Julia often visited him at army camps, sometimes bringing their children. When Grant became president, she bloomed into a popular first lady, hosting social receptions while remaining a close advisor to her husband, even meeting with cabinet members and politicians.

Early Military Career

During the Mexican-American War, Grant served as a quartermaster, efficiently overseeing the movement of supplies. Serving under General Zachary Taylor and later under General Winfield Scott, he closely observed their military tactics and leadership skills. After getting the opportunity to lead a company into combat, Grant was credited for his bravery under fire. He also developed strong feelings that the war was wrong and that it was being waged only to increase America's territory for the spread of slavery.

In 1852, he was sent to Fort Vancouver, in what is now Washington State. He missed Dent and his two sons—the second of whom he had not yet seen at this time—and thusly became involved in several failed business ventures to get his family to the coast, closer to him.

He began to drink, not unlike other soldiers—and many other Americans—in an era where alcohol consumption rates were much higher than today. Grant’s thin frame and small stature meant he showed the effects of alcohol quicker than many others. Grant developed a reputation for drinking that dogged him throughout his military career. Still, most of these episodes occurred, especially in the early years of his service, when he was separated from his family and sent to ever-more isolated army postings that left him bored and lonely with little else to do.

In the summer of 1853, Grant was promoted to captain and transferred to Fort Humboldt on the Northern California coast, where he had a run-in with the fort's commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Robert C. Buchanan. On July 31, 1854, Grant resigned from the Army amid allegations of heavy drinking and warnings of disciplinary action.

In 1854, Grant moved his family back to Missouri, but the return to civilian life led him to a low point. He tried to farm land given to him by his father-in-law, but this venture proved unsuccessful after a few years. Grant then failed to find success with a real estate venture and was denied employment as an engineer and clerk in St. Louis. To support his family, he was reduced to selling firewood on a St. Louis street. Finally, in 1860, he humbled himself and worked in his father's tannery business as a clerk, supervised by his two younger brothers.

Ulysses S. Grant and Slavery

Like many of his contemporaries, Grant’s involvement with slavery was complicated. An abolitionist father raised him and personally professed his dislike of slavery. But he married the daughter of a slave-holding plantation owner, and the Dent family’s enslaved population often worked alongside Grant at the farm he built on land given to him by his father-in-law. In the late 1850s, he was transferred ownership of an enslaved man, William Jones. In 1859, Grant freed Jones despite severe financial difficulties that might otherwise have led him to sell Jones for a profit.

While Grant’s service in the Civil War was initially inspired by his desire to defend and reunite the Union, he supported Abraham Lincoln’s decision to issue the Emancipation Proclamation, which freed enslaved peoples in Confederate states that had seceded. When the Proclamation went into effect in January 1863, Grant ensured the newly freed formerly enslaved were cared for when they reached Union lines and encouraged Lincoln to allow formerly enslaved men to join the Union Army, which he believed would significantly weaken the Confederate cause.

American Civil War

On April 12, 1861, Confederate troops attacked Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor, South Carolina. This rebellion sparked Grant's patriotism, and he volunteered his military service. Again, he was initially rejected for positions, but with the aid of an Illinois congressman, he was appointed a colonel and took command of an unruly 21st Illinois volunteer regiment. Applying lessons he'd learned from his commanders during the Mexican-American War, Grant saw that the regiment was combat-ready by September 1861. By that point, he had been promoted to brigadier general.

When Kentucky's fragile neutrality fell apart in the fall of 1861, Grant and his volunteers took the small town of Paducah, Kentucky, at the mouth of the Tennessee River. In February 1862, in a joint operation with the U.S. Navy, Grant's ground forces applied pressure on Fort Henry and Fort Donelson, taking them both. These battles are the earliest significant Union victories of the American Civil War. After the assault on Fort Donelson, Grant earned the moniker "Unconditional Surrender Grant" and was promoted to major general of volunteers.

READ MORE: How Ulysses S. Grant Earned the Nickname "Unconditional Surrender Grant"

Battle of Shiloh

In April 1862, Grant moved his army cautiously into enemy territory in Tennessee in what would later become known as the Battle of Shiloh (or the Battle of Pittsburg Landing), one of the Civil War's bloodiest battles. Confederate commanders Albert Sidney Johnston and P.G.T. Beauregard led a surprise attack against Grant's forces, with fierce fighting occurring at an area known as the "Hornets' Nest" during the first wave of assault. Confederate General Johnston was mortally wounded, and his second-in-command, General Beauregard, decided against a night assault on Grant's forces. Reinforcement finally arrived, and Grant defeated the Confederates during the second day of battle.

The Battle of Shiloh proved to be a watershed for the American military and a near disaster for Grant. Though President Abraham Lincoln supported him, Grant faced heavy criticism from members of Congress and the military brass for the high casualties, and for a time, he was demoted. A war department investigation led to his reinstatement.

Vicksburg Siege

The Union war strategy called for taking control of the Mississippi River and cutting the Confederacy in half. In December 1862, Grant moved overland to take Vicksburg—a key fortress city of the Confederacy—but Confederate cavalry raider Nathan Bedford Forest stalled his attack due to getting bogged down in the bayous north of Vicksburg. In his second attempt, Grant cut some, but not all, of his supply lines, moved his men down the western bank of the Mississippi River, and crossed south of Vicksburg. Failing to take the city after several assaults, he settled into a long siege, and Vicksburg finally surrendered on July 4, 1863. Grant was named major general of the regular U.S. Army.

Though Vicksburg marked Grant's most outstanding achievement thus far and a morale boost for the Union, rumors of Grant's heavy drinking followed him through the rest of the Western Campaign. Grant suffered from intense migraine headaches due to stress, which nearly disabled him and only helped to spread rumors of his drinking, as many chalked up his migraines to frequent hangovers. However, his closest associates said that he was sober and polite and displayed deep concentration, even amid a battle. When confronted by these rumors, President Abraham Lincoln was unperturbed, reportedly offering to send a case of Grant’s favorite whisky to other Union generals in the hope of achieving Grant’s stunning military results.

Battle for Chattanooga

In January 1863, the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect, freeing enslaved peoples in the Confederate states that had seceded from the Union.

In October 1863, Grant took command at Chattanooga, Tennessee. The following month, from November 22 to November 25, Union forces routed Confederate troops in Tennessee at the battles of Lookout Mountain and Missionary Ridge, known collectively as the Battle of Chattanooga. The victories forced the Confederates to retreat into Georgia, ending the siege of the vital railroad junction of Chattanooga—and ultimately paving the way for Union General William Tecumseh Sherman's Atlanta campaign and march to Savannah, Georgia, in 1864.

Union Victory

Grant saw the military objectives of the Civil War differently than most of his predecessors, who believed that capturing territory was most important to winning the war. Grant adamantly believed that taking down the Confederate armies was most important to the war effort and, to that end, set out to track down and destroy General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia.

In March 1864, Grant was named lieutenant general of the U.S. Army (the first person to achieve this rank since George Washington) and given command of all U.S. armies. He quickly set out to congruent Lee, and from March 1864 until April 1865, Grant doggedly hunted for Lee in the forests of Virginia, all the while inflicting unsustainable casualties on Lee's army.

On April 9, 1865, Lee surrendered his army, marking the end of the Civil War. The two generals met at a farm near the village of Appomattox Court House, and a peace agreement was signed. In a generous gesture, Grant allowed Lee's men to keep their horses and return to their homes, taking none of them as prisoners of war.

Presidency

During the post-war reorganization, Grant was promoted to full general and oversaw the military portion of Reconstruction. In 1867, Grant was caught up in a scandal involving Republican Andrew Johnson's fight with the Radical Republican wing of his party. Johnson tried to remove his Secretary of War, who had often sided with the Radical Republican wing over the more robust implementation of Reconstruction in the South and initially tried to replace him, Grant, all without the necessary Congressional approval. During the subsequent uproar, Grant resigned from the position. Still, Johnson’s determination to proceed with his plan with a different appointee made him the first U.S. president to be impeached.

Despite having never been elected to any previous political office, in 1868, Grant ran for president on the Republican ticket and was elected the 18th president of the United States. When he entered the White House the following year, Grant was not only politically inexperienced but also—at the age of 46—the youngest president theretofore.

Grant had many achievements as president, pushing through ratification of the 15th Amendment, creating the forerunner to the National Weather Service and America’s first national park (Yellowstone), instituting the first Civil Service Commission (aimed at replacing the corrupt patronage system that controlled many government jobs), working with Native American leaders to develop a peace plan in the West and naming Eli Parker as the first Native American head of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Grant also oversaw the creation of the U.S. Justice Department, using the new department, in part, to help strengthen and enforce laws aimed at curbing the rise of the newly formed Ku Klux Klan.

However, Grant’s administration faced numerous setbacks, including a prolonged economic depression in 1873. Though scrupulously honest, Grant became known for appointing people who were not of good character, and his presidency today is often more remembered for its notable scandals than its successes. In 1869, two Wall Street speculators (whom Grant knew from before becoming president) attempted to corner the gold market and ensnare Grant in their scheme, leading to a financial panic. In 1875, Grant’s private secretary was embroiled in a scandal that intended to deprive the federal government of millions of dollars in revenues from liquor taxes, and even Grant’s brother was later involved in a kickback scheme involving military contracts. By the end of his second term, several members of Grant’s cabinet had been accused of taking bribes. Grant called for proper legal investigations for those involved, and during his final address to Congress in 1876, he discussed his lack of political experience upon entering the office and the resulting issues during his presidency, noting, “Failures have been errors of judgment, not of intent.”

Final Years and Death

After leaving the White House, Grant's lack of success in civilian life continued once again. He became a partner of the financial firm Grant and Ward only to have his partner, Ferdinand Ward, embezzle investors' money. The firm went bankrupt in 1884, as did Grant. That same year, Grant learned that he had throat cancer, and though his military pension was reinstated, he was strapped for cash.

Grant began selling short magazine articles about his life and then negotiated a contract with a friend, famed novelist Mark Twain, to publish his memoirs. The two-volume set sold 300,000 copies, becoming a classic work of American literature. Ultimately, the work earned Grant's family nearly $450,000.

READ MORE: The Unlikely Friendship of Mark Twain and Ulysses S. Grant

Grant died on July 23, 1885—just as his memoirs were being published—at 63, in Mount McGregor, New York. He was buried in New York City, with more than 1.5 million attending his funeral. His temporary burial site was greatly expanded and became popularly known as Grant’s Tomb, the largest mausoleum in North America. In 1914, Grant became the face of the U.S. Treasury’s $50 bill, and in 1922, to mark the centennial of his birth, the U.S. Mint released gold dollars and silver half dollars featuring Grant, partly to raise funds to preserve his Ohio birthplace.

Grant’s reputation has seen notable shifts over time. While many of his contemporary Americans lauded him for his Civil War service and liked Grant personally, the scandals surrounding his presidency led him to be ranked among the most unsuccessful presidents in history. Historians and writers began reappraising Grant's legacy in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. They noted his success in preserving the Union in the post-war years that saw it roiled by debates over the federal government’s role in southern Reconstruction. He has been lauded for his attempted civil service reforms, his vigorous defense of the civil liberties of African Americans, and his policy towards Native Americans (Grant favored giving them American citizenship nearly 50 years before that became a reality). A highly skilled military commander, Grant could not translate those talents to the presidency, with both his personal and political naivete regarding those surrounding him obscuring his notable achievements.

Quotes

- Whatever may have been my political opinions before, I have but one sentiment now. That is, we have a government, and laws and a flag and they must all be sustained.

- I have never advocated war except as a means of peace.

- [My] failures have been errors of judgment, not of intent.

- A verb is anything that signifies to be; to do; to suffer; I signify all three.

- It occurred to me at once that [my enemy] had been as much afraid of me as I had been of him. This was a view of the question I had never taken before; but it was one I never forgot afterwards.

- I know no method to secure the repeal of bad or obnoxious laws so effective as their stringent execution.

- I never wanted to get out of a place as much as I did to get out of the presidency.

- No terms except an unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted.

- I don't know anything of party politics, and I don't want to.

- I know only two tunes: One of them is 'Yankee Doodle' and the other isn't.

- The art of war is simple enough. Find out where your enemy is. Get at him as soon as you can. Strike him as hard as you can, and keep moving on.

- I can't spare this man—he fights.

Fact Check: We strive for accuracy and fairness. If you see something that doesn’t look right, contact us!

The Biography.com staff is a team of people-obsessed and news-hungry editors with decades of collective experience. We have worked as daily newspaper reporters, major national magazine editors, and as editors-in-chief of regional media publications. Among our ranks are book authors and award-winning journalists. Our staff also works with freelance writers, researchers, and other contributors to produce the smart, compelling profiles and articles you see on our site. To meet the team, visit our About Us page: https://www.biography.com/about/a43602329/about-us