The life and death of Henry VIII’s 'most faithful servant'

The publication of Hilary Mantel's Wolf Hall in 2009 transformed Thomas Cromwell's reputation from a scheming, ruthless villain of history into a loyal, humorous and streetwise hero. In real life, Cromwell enjoyed a spectacular rise from the son of a Putney blacksmith to the chief minister of Henry VIII.

A man of exceptional ability and with an enormous capacity for hard work, Cromwell dominated England's political and religious life for a decade. He ruthlessly dispatched those who stood against him and his royal master, notably his rival Thomas More and Henry’s notorious second wife Anne Boleyn.

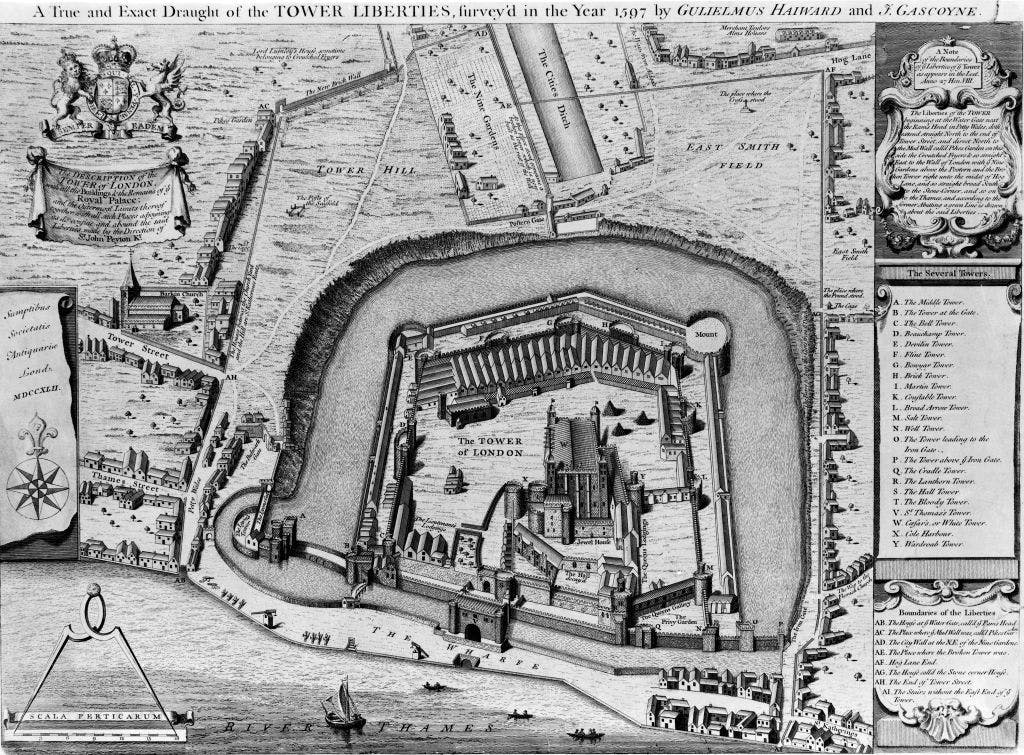

His downfall came after he arranged Henry’s short-lived marriage to Anne of Cleves. He was imprisoned at the Tower of London before his execution in 1540.

Image: Thomas Cromwell, Earl of Essex after Hans Holbein the Younger. © National Portrait Gallery, London

Humble beginnings

The man who would one day become the most powerful in England was of such humble origins that nobody can be sure when or where he was born.

The likeliest date for his birth is 1485, which would be appropriate, given it was the year the Tudors seized the throne.

Did you know?

In later life, Thomas Cromwell made the unlikely claim that his mother was 52 when she bore him.

Cromwell's birthplace is often cited as Putney, which at the time was a small village by the Thames, west of the City of London.

The records suggest that Thomas was the youngest of three children, and the only boy, born to Walter Cromwell and his wife Katherine née Meverell.

His father was an enterprising man with a number of different professions, including blacksmith and brewer. He owned a hostelry, called the Anchor, which was situated close to their home at the top of Brewhouse Lane.

Image: A Tudor tavern. © Getty Images

Despite being a successful businessman, Walter Cromwell was often in trouble with the law. His most serious conviction came in 1477 when he was found guilty of assault.

Although the sources reveal little of Thomas's relationship with his father, a remark he made many years later suggests he had inherited some of Walter's less admirable traits. He confided to his friend Archbishop Thomas Cranmer what a 'ruffian he was in his young days'. But he was eager to escape the family home.

Trouble

Walter Cromwell was fined by the courts on no fewer than 48 occasions for watering down the beer that he sold.

A life marred by tragedy

By the time Cromwell returned to England in around 1512 he had both the experience and contacts to set himself up as a merchant. But like his father, he was not content to follow just one career path and soon began practising law. It was this profession that would win him greatest renown.

It is an indication of Cromwell's burgeoning career that in 1514 he married Elizabeth Williams (née Wyks), a wealthy widow whose father had served Henry VII. It would prove a successful marriage and produced at least three children: Alice (or Anne), Grace and Gregory.

The family lived in Fenchurch, on the eastern side of the City of London, a popular area with merchants, before moving to nearby Austin Friars.

The contemporary sources provide very few details of Cromwell's marriage and family life, but it appears to have been settled and harmonious.

Tragically, Cromwell lost both his wife and daughters to the sweating sickness within the space of a year (1528/9). He never remarried and instead focused all of his affection upon his surviving child, Gregory.

Did you know?

Sweating sickness symptoms came suddenly and death could occur in under 24 hours.

Cardinal Thomas Wolsey

By the time of his wife and daughters' death, Cromwell was one of the most successful businessmen in London. He had also secured an influential patron in the form of Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, Henry VIII's chief minister.

Like Cromwell, Wolsey was of lowly birth, being the son of a butcher. Yet he had risen to become the most powerful man in England, next to the King, and Henry was utterly reliant upon him. In 1519, Wolsey appointed Cromwell to council and he soon became one of his most trusted servants.

The Cardinal mostly employed Cromwell on legal business, including the dissolution of some small religious houses in order to pay for his new college at Oxford – something that perhaps sowed the seeds for Cromwell's later service to the King.

Image: Cardinal Thomas Wolsey. © Christ Church Picture Gallery

Cardinal Wolsey's fall from power

In stark contrast to the majority of Wolsey's sizeable entourage, Cromwell stood by his patron when he was thrown out of office for failing to secure the annulment of the King's marriage to Katherine of Aragon, so that he might marry Anne Boleyn.

Even the Imperial ambassador Eustace Chapuys, who had no liking for either Wolsey or Cromwell, admitted: 'At his master’s fall he [Cromwell] behaved very well towards him.'

Image: Wolsey gave his sizable palace at Hampton Court to Henry VIII sometime before his fall, perhaps in an attempt to win back the King's favour.

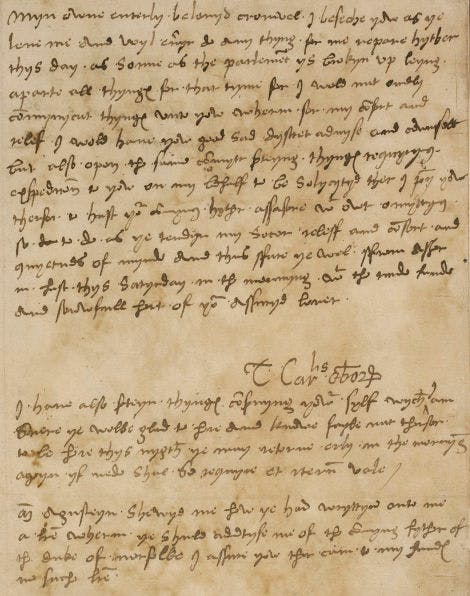

Below: Wolsey's letter to Cromwell, in which he praises his servant's 'good, sad, discreet advice and counsel'. © The British Library Board, Cotton Vespasian F. XIII, f.147

My own entirely beloved Cromwell: I beseech you, as you love me and will ever do anything for me, repair hither this day... I would communicate things to you, wherein for my comfort and relief, I would have your good, sad, discreet advice and counsel... From Esher, in haste, this Saturday in the morning with the rude hand and sorrowful heart of your assured friend.

Letter from Thomas Wolsey in distress to Thomas Cromwell

Cromwell enters Henry VIII's service

When Cromwell went to court to petition the King to pardon his fallen minister, Henry was impressed by his loyalty, not to mention his quick wittedness, irreverence and obvious ability. Cromwell's cosmopolitan upbringing also gave him an edge over the more nobly born men of court.

Cromwell soon began to employ his considerable legal talents in the King's 'Great Matter' – the annulment of his marriage to Katherine of Aragon. In so doing, he not only impressed Henry, but won the notice of Anne Boleyn. The two rapidly became allies, particularly after Wolsey’s death in 1530.

Courtiers were quick to comment upon Cromwell's spectacular rise. He was described as 'the most secret and dear counsellor unto the king' and 'the man who enjoys most credit with the king'.

Image: King Henry VIII, after Hans Holbein the Younger. © National Portrait Gallery

Master of the Jewels

In April 1532, Henry awarded Cromwell his first formal office, that of Master of the Jewels, which required regular visits to the Jewel House at the Tower of London.

Many more promotions would follow, bringing Cromwell great riches as well as immense power. His private businesses were also continuing to flourish.

Cromwell's Holbein Portrait

It was almost certainly to celebrate his appointment as Master of the Jewels that Cromwell commissioned Hans Holbein, the most celebrated artist of the age, to paint his portrait in around 1532-33.

The result is one of the most extraordinarily revealing portraits of the Tudor age. Far from flattering the sitter, it offers a brutally honest appraisal of a portly, middle-aged man who is hard at work in his study.

Image: Thomas Cromwell, Earl of Essex after Hans Holbein the Younger. © National Portrait Gallery, London

The Dissolution of the Monasteries

In May 1533, the King's marriage to Katherine of Aragon was finally annulled and Anne Boleyn (whom he had married the previous January) was crowned in June that year. This ushered in one of the most turbulent periods in British history.

Having failed to secure the Pope's permission for the annulment, Henry broke with Rome and established a separate Church of England over which he was the Supreme Head.

Cromwell oversaw all the seismic religious reforms that followed, including – most controversially – the Dissolution of the Monasteries. The piecemeal destruction of these great religious houses brought the King enormous wealth, but also sparked widespread opposition.

Thomas More

One of the most prominent opponents of the Reformation was the Lord Chancellor, Thomas More. He refused to take the Oath of Supremacy, which recognised the King's new role, and eventually resigned his position.

Henry and Cromwell brought considerable pressure to bear in trying to persuade More to conform, but when he continued to refuse he was imprisoned in the Tower of London and executed in July 1535.

Image: Thomas More bids a final farewell to his daughter, Margaret Roper, outside the Tower of London in 'The Meeting of Thomas More with his daughter after his sentence' as imagined by William Frederick Yeames, 1863.

The elimination of Anne Boleyn

The woman at the heart of all this controversy had soon proved a disappointment as a royal wife. Anne Boleyn had been pregnant at the time of her marriage to Henry, but the child she carried was a girl (the future Elizabeth I) rather than the hoped-for son.

A series of miscarriages followed, the last of which took place in January 1536. This seems to have prompted Henry to instruct Cromwell to get him out of the marriage.

Image: Anne Boleyn by an unknown English artist. © National Portrait Gallery

Anne Boleyn beheaded

Drawing on rumour and hearsay prompted by Anne's flirtatious behaviour, Cromwell constructed a case of adultery against her that involved no fewer than five men, including her own brother George.

Anne was arrested on 2 May 1536 and taken to the Tower of London, where she was tried and found guilty a little over two weeks later. Cromwell was among the witnesses who gathered to see her beheaded there on 19 May.

The King's right-hand man

This was the zenith of Cromwell's career. Not only had he rid the King – and himself – of a woman who had become a dangerous enemy, but he quickly allied his family with the new queen, Jane Seymour, to whom Henry was betrothed the day after Anne’s execution.

But it was not long before cracks began to appear in Cromwell and Henry's relationship.

Simmering discontent against the Reformation broke out into open rebellion with the Pilgrimage of Grace in October 1536. The rebels made it clear that the focus of their fury was 'that heretic Cromwell', not the King.

Henry's faith in Cromwell was shaken and he began to distance himself from his chief minister. On one notorious occasion in 1538, he even used violence towards his former favourite. One courtier described how the hapless minister was 'well pommelled about the head, and shaken up, as it were a dog'.

By 1539, Cromwell was desperate to claw back favour and soon thought he had found the perfect means.

Jane Seymour had died after giving birth to the King's longed-for son, Edward, in 1537. The search for a fourth wife for Henry had begun almost immediately, and Cromwell found a new bride for his royal master.

Image: Jane Seymour in 1536, by Hans Holbein the Younger © Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria / Bridgeman Images

'I like her not!'

The candidate whom Cromwell put forward was Anne of Cleves, a German princess who would bring England a powerful new alliance. Before he would agree to the idea of a new bride, Henry dispatched Holbein to paint her portrait.

Anne's portrait so delighted Henry that marriage negotiations began immediately and Anne made her way to England in December 1539.

But when Henry met her in person, he was appalled. 'I like her not! I like her not!' he shouted at the beleaguered Cromwell, complaining that Anne was 'nothing so well as she was spoken of'. The marriage was annulled a few months later.

Image: Portrait of Anne of Cleves, 1539 by Hans Holbein the Younger. © Louvre, Paris, France / Bridgeman Images

Cromwell's enemies attack

Contrary to popular belief, the Anne of Cleves disaster was not the end for Cromwell. Although one contemporary gleefully observed 'Cromwell is tottering', the King soon forgave him and in April 1540 he created him Earl of Essex.

This infuriated Cromwell's enemies – chief among whom was the Duke of Norfolk – and made them determined to get rid of this low-born upstart for good. They therefore started a whispering campaign against Cromwell and told Henry that he was plotting to rebel against him.

It took little to ignite the suspicions of this ageing and paranoid King, who did not hesitate to order Cromwell's arrest on charges of treason and heresy.

'I cry for mercy, mercy, mercy.'

Cromwell was taken to the Tower on 10 June 1540. Given that he was the country’s most renowned lawyer, his enemies dare not risk putting him on trial so they persuaded the King to bring a bill of attainder before Parliament.

The bill was passed in late June and Cromwell was condemned to die. His only chance of survival was to persuade Henry to pardon him.

He therefore wrote a series of impassioned letters from the Tower, the last of which ended with a desperate postscript: 'Most gracious prince, I cry for mercy, mercy, mercy.'

Image below: Thomas Cromwell, Earl of Essex © National Portrait Gallery, London

Written at the Tower this Wednesday, the last of June, with the heavy heart and trembling hand of your Highness’s most heavy and most miserable prisoner and poor slave. Most gracious prince, I cry for mercy, mercy, mercy.

Thomas Cromwell, writing to Henry VIII from the Tower of London

The execution of Thomas Cromwell

The King did not heed his words and Cromwell was executed on 28 July 1540. It took three blows of the axe by 'the 'ragged and butcherly' executioner to sever his head.

When this had been displayed on London Bridge, it was reunited with the rest of his remains and buried at the Tower's Chapel Royal of St Peter ad Vincula alongside his erstwhile rivals Anne Boleyn and Thomas More.

Memorials

Cromwell's name can be found on a plaque just inside the door of the Chapel Royal of St Peter ad Vincula, and there is a memorial on the site of his execution on Tower Hill.

Cromwell's legacy

Thomas Cromwell had been one of the most exceptional royal servants in history, masterminding widespread reforms in every aspect of England’s religious, political and social life.

A man of genuine religious conviction, Cromwell paid for the translation of the Bible into English so that all Henry’s subjects had ready access to God's word. He personally drafted numerous statutes revolutionising government and administration, and significantly boosted the power of Parliament.

Henry VIII's 'Most faithful servant'

Thomas Cromwell himself once declared 'that there was nothing he desired so much in this world as to leave a good name behind him.' Even before his death, he had divided opinion among contemporary commentators.

His adversary Cardinal Reginald Pole denounced him as 'an agent of Satan sent by the devil to lure King Henry to damnation'.

By contrast, John Foxe credits the minister with spearheading the English Reformation and claims that his whole life was 'nothing else but a continual care and travail how to advance and further the right knowledge of the gospel and reform of the house of God'.

Perhaps the most compelling assessment of Cromwell was that by Henry VIII himself. Within just a few short weeks of his chief minister's demise, the King was heard to lament the loss of 'the most faithful servant he had ever had'.

About the author

Tracy Borman

Tracy Borman is joint Chief Curator at Historic Royal Palaces, the independent charity that looks after the Tower of London, Hampton Court Palace, the Banqueting House, Kensington Palace, Kew Palace and Hillsborough Castle and Gardens. Her published books include Thomas Cromwell: The Untold Story of Henry VIII’s Most Faithful Servant, Henry VIII and the Men Who Made Him, The Private Lives of the Tudors, Elizabeth's Women: The Hidden Story of the Virgin Queen and The Story of the Tower of London.

Listen to the podcast

In this episode Historic Royal Palaces’ Chief Curator Tracy Borman explores one of her favourite topics, the turbulent life of Thomas Cromwell and his relationship with the English Reformation. This talk was recorded live at Hampton Court Palace in 2017.

More episodesBROWSE MORE HISTORY AND STORIES

Henry VIII, Terrible Tudor?

Who was the real Henry VIII?

Anne Boleyn

How did Anne Boleyn become queen and why did Henry VIII execute her?

Anne of Cleves: The Great Survivor

Anne of Cleves was Queen of England and Henry VIII's fourth wife for just over six months. For many she was a brief footnote in Henry VIII's quest to secure the Tudor dynasty. But there is more to her story than meets the eye.

EXPLORE WHAT'S ON

- Tours and talks

Tower Twilight tours

Dare you visit the Tower at night and take one of our Twilight Tours? Discover secrets of the Tower's history with after-hours access.

- Until 31 March 2024

- 19:00 - 20:30 (approximately 90 minutes)

- Tower of London

- Separate ticket (advance booking required)

- Things to see

Tower Green & Scaffold site

Walk in the footsteps of those condemned to execution at the Tower of London on Tower Green and the Scaffold Site.

- Open

- Tower of London

- Included in palace admission (members go free)

- Things to see

Torture at the Tower exhibition

Prepare to be shocked by stories of the unfortunate prisoners who were tortured within the walls of the Tower of London.

- Open

- Tower of London

- Included in palace admission (members go free)