Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Tuesday, 30 May 2023, 08:25

Unit 9: Drama, television and film

Introduction

In this section, you will learn about the use of Scots language in drama, television and film. There have been periods in the last two centuries when Scots was considered appropriate only for limited stage, television and film use, usually for quaint or comic effect, reinforced by the tradition of Scots language comedy derived from the music hall and pantomime.

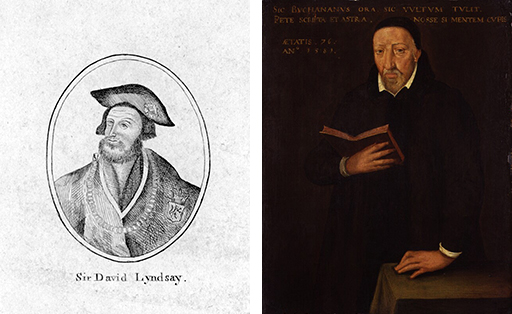

There are, of course, stage plays in Scots of major importance in the historical development of Western theatre, like Sir David Lindsay’s Ane Satire of the Thrie Estaitis (1552–4) and Allan Ramsay’s The Gentle Shepherd (1729). These works, however, came to be neglected, not least because they depended originally on acting conventions that fell out of fashion, especially when Konstantin Stanislavski’s naturalistic acting style became the dominant dramatic performance mode it is now throughout the world.

Further, both Lindsay and Ramsay employed Scottish theatre’s typical intertwining of the serious and comic, which later centuries often regarded as inappropriate and, in Lindsay’s case, obscene. Over the last century, however, there has been a rediscovery of the potential of the dramatic use of Scots for both serious and comic impact.

This section will introduce you to the history of Scots in drama and, draw your attention to the 20th century revival of the use of Scots as a serious stage language. It will also review the ways in which Scots has been presented and exploited on TV and consider the questions of accessibility that often appear to arise when Scots is used in film. Finally, it will briefly discuss issues that underlie the dramatic use of Scots language.

Important details to take notes on throughout this section:

The history of Scots as a stage language from the 16th century onwards

Scots language drama over the 20th century

Developments in the use of Scots in television drama

Scots language in film

Underlying issues affecting the use of Scots in dramatic performance-writing.

Activity 1

Before commencing your study of this unit, you may wish to jot down some thoughts on the five important details we suggest you take notes on throughout this unit. You could write down what you already know about each of these five points, as well as any assumption or question you might have.

9. Introductory handsel

A Scots word and example sentence to learn:

Definition: A mummer, masquerader, esp. in mod. times one of a party of children who go in disguise from door to door at various festivals, esp. Halloween, Christmas Eve and Hogmanay.

Example sentence: “Dinnae tak a fleg; it’s only the guisers ben the hoose.”

English translation: “Don’t be scared; it’s only the masqueraders through in the front room.”

Please note: In many areas of Scotland guisers still go around houses at festivals like Halloween, masquerading in costume and presenting set pieces in return for token rewards: pieces of fruit or small coins.

This Scottish performance tradition was exported by emigrants to the United States where it became transformed into the American form of ‘Trick or Treat’. This form has been re-exported to Scotland and the rest of Britain, where its origins are often forgotten.

Activity 2

Click to hear the sentence above read by a Scots speaker.

You can then make your own recording and play it back to check your pronunciation.

Transcript

Listen

Dinnae tak a fleg; it’s only the guisers ben the hoose.

Model

Dinnae tak a fleg; it’s only the guisers ben the hoose.

Go to the Dictionary of the Scots Language for a full definition of the word

Language Links

You might have heard people in Scotland talk about a person, often a man, being a guiser, or in English ‘geezer’ – an odd looking person. And you will hear people in Scotland talk about going guising at Halloween. The use in connection with Halloween comes much closer to the original meaning of the word, to go masquerading or to be a masquerader, to disguise oneself.

The Scots words guise, guising and guiser all originate in Old French guise “manner or fashion” and desguiser "disguise, change one's appearance". In today’s French you will come across the verb se déguiser which means to disguise oneself or to masquerade; this too comes from Old French desguiser.

Related word:

Definition: n. 1. A fright, a scare.

Example sentence: “Dinnae tak a fleg; it’s only the guisers ben the hoose.”

English translation: “Don’t be scared; it’s only the masqueraders through in the front room.”

Activity 3

Click to hear the sentence above read by a Scots speaker.

You can then make your own recording and play it back to check your pronunciation.

Transcript

Listen

“Dinnae tak a fleg; it’s only the guisers ben the hoose.”

Model

“Dinnae tak a fleg; it’s only the guisers ben the hoose.”

Go to the Dictionary of the Scots Language for a full definition of the word

Please note: This is an image of an exhibit in the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh. Peden was a leading Covenanter who spent years as a fugitive, holding open-air conventicles and dodging the authorities. This mask on display here was his disguise.

Working with DSL entries

Here you’ll learn to interpret in more detail a DSL dictionary entry. In this example, an extract from the ‘guiser’ entry in the DSL, we will show you what the different parts of the entry mean. In conjunction with the information in this box, visit the overview of the abbreviations used in the DSL to help you to fully decode this entry.

We have broken up the entry on the word guiser into smaller parts. For each part we provide a commentary which ‘translates’ the part and gives additional information where appropriate.

GUISER, n., v.

[Noun and verb – you might have noticed that many Scots words are the same as nouns or verbs]

Also guisar, guizer, -ar, gyser, -ar; guisard, -art, guiz-, g(u)ys-, g(u)yz-, ¶guiserd (Hdg. 1896 J. Lumsden Poems 145), ¶-yard (m.Sc. 1927 J. Buchan Witch Wood x.), ¶geizart (Rxb. 1925 E. C. Smith Mang Howes 14), ¶gayzard.

[This part of the entry lists the different spellings of the word that have been found – as Scots is not a language with a common standard, also for the written language – there are often different spellings for the same word, in many instances these are, for example, related to different pronunciations in the dialects;

It also shows where particular and more unusual spellings have been found and when, i.e. ‘guiserd’ on page 145 in the poem collection by James Lumsden published in Haddington; or ‘guisyard’ in the modern Scots on page x. of John Buchan’s novel Witch Wood published in 1927]

[′gɑezər -ərd, -ərt]

[This part shows the phonetic transcription of the different spellings, which explains how these would have to be pronounced; if you are not familiar with phonetic script, here is an explanation]

I.n. 1. A mummer, masquerader, esp. in mod. times one of a party of children who go in disguise from door to door at various festivals, esp. Halloween, †Christmas Eve and †Hogmanay (Sc. 1770 Hailes Ancient Sc. Poems 286). Gen.Sc. and n.Eng. dial. Also fig.

[This is the first entry describing one of the meanings of the noun; it also shows one use that has been found in a publication from 1770 but appears to have died out today, which that describes people disguising themselves on Christmas Eve and Hogmanay – this use was seen in Ancient Scottish Poems. Published from the MS. of G. Bannatyne (Edited with a preface and glossary by Sir David Dalrymple, Lord Hailes) published in 1770, p.286; the word is general Scots and also northern English dialect; it can also be used figuratively or metaphorically]

Edb. 1773 Edb. Ev. Courant (18 Jan.): Some boys diverting themselves through the streets as guizards [at Auld Yule].

[Finally, this part of the first entry shows an example of how the noun is used through a quote where the search term ‘guiser’ in one of its variants appears, e.g. in the Edinburgh Evangelical Courant edition of the 18 January 1773]

Activity 4

You have already worked widely with the Dictionary of the Scots Language (DSL) in all units of this course. The main use of the dictionary has so far been to find meanings of Scots words to help you understand and translate Scots sentences/texts.

In this activity, you will enhance your dictionary skills and try out working with a different aspect of the dictionary: etymology – changes of meaning over time as well as locations. Because of the dialect diversity present in Scotland, the DSL identifies the locations at which Scots words have been used with different meanings or spellings.

9.1 Scots on stage (1700–)

In this section you will learn about the history of Scots language drama and, briefly, theatre in Scotland and more recent use of Scots on stage, television and in film. The related activities will assist you in developing your knowledge and experience of the use of Scots in performance and, so, your understanding of Scots language. You are encouraged to seek out the texts mentioned later in libraries and also as performed in clips on YouTube.

There is a myth that theatre in Scotland after the 1560 Reformation was suppressed for centuries. In fact, as Anna Mill says in her masterly study of medieval plays in Scotland, ‘the drama was employed by the early reformers as a valuable means of propaganda’ (1927, p. 88).

Leading up to the Reformation, the Catholic Church with its widespread clerks’ plays had used drama to spread its version of Christianity and those who opposed its organisation and values had also used drama to promote their views. The playwright and friar John Kyllour’s Historye of Christis Passioun, performed on Good Friday 1535 on the Stirling playfield in front of King, court and townspeople, clearly attacked the contemporary clergy’s pomposity. The Catholic hierarchy hunted him down and he was burned at the stake in Edinburgh in 1539.

When in the next year the first version of David Lindsay’s Thrie Estaitis, a satire on clerical and political corruption, was performed at court in Linlithgow, Lindsay was protected by his high position at court, as Lindsay was a Scottish herald and makar, who gained the highest heraldic office of Lyon King of Arms. Yet, after his play, expanded for the public, was presented in Cupar (1552) and Edinburgh (1554), the script was burned publicly. Suppression of controversial theatre preceded the Scottish Reformation.

As in many other countries, drama and theatre was lively and alert to current topics, participating in dynamic debate. It was for that reason that over the centuries theatre was often watched carefully by the authorities: throughout Britain, for example, after 1737 the Lord Chamberlain, the official in charge of the royal household, acted as theatre censor until that duty was abolished as recently as 1968.Much of the impact of Lindsay’s play lay in its vibrant Scots. In fact, Lindsay was not the first major playwright Scotland produced.

Around 1540 George Buchanan produced two original plays, Jephthes and Baptistes, two versions of Greek tragedies which had a Europe-wide impact on theatrical development, powerfully influencing the development of French neo-classical drama by playwrights like Corneille and Racine in the next century and being performed and translated across Europe from Portugal to Poland for well over two hundred years. But Buchanan’s plays were in Latin and Lindsay’s were, like the folk drama that surrounded him, in Scots.

During the early modern period, from about 1500 to 1800, Scottish schoolchildren were required to perform plays at least annually for Kirk Sessions and local bigwigs, not least in order to develop their public speaking skills – a tradition that has lasted to the present day with schoolchildren performing plays, for example the Christmas play, at their school.

The plays performed by children before 1800 might be classical or contemporary, but what they mark is the strength of a theatre tradition outside of the professional playhouse, a form which only came to prominence in Scotland during the 18th century, by the end of which it was wide-spread. In spreading, it could draw on the long tradition of serious drama in the schools that produced the governing classes – the lawyers, ministers, politicians and teachers – and on the parallel forms of folk and amateur drama.

Many theatre plays were written in English, but so were many in Scots, like Allan Ramsay’s Jacobite-supporting The Gentle Shepherd (1729).

By the 19th century, as Walter’s Scott’s novels emerged to public acclaim, they were quickly adapted for the stage, and toured throughout Scotland, where their main home, but not only source, was Edinburgh’s Theatre Royal. These dramas drew on Scots dialogue, especially for local characters, and constituted what was called the National Drama. Through that century such plays marked a distinctive Scottish genre, using Scots for key dialogue and asserting the individuality of Scottish history, literature and culture.

While this long tradition of Scottish drama and theatre did not produce the sort of masterpieces which appeared within the English theatre, one should never underestimate the range and depth of Scottish theatrical history, especially since the Reformation, and the importance of Scots language drama within that tradition.

Certainly, in Ane Satire of the Thrie Estaitis and The Gentle Shepherd it produced two lasting masterpieces in Scots language, while The Gentle Shepherd and the Scot John Home’s Douglas (1756), the latter written in English, were two of the most produced and successful plays in British theatre in their century and for decades beyond.

In this next activity you will identify the most important language information from this section.

Activity 5

Which of these highly influential plays by Scottish playwrights were written in which language? Select the correct answer for each play.

a.

English

b.

Latin

c.

Scots

The correct answer is a.

a.

English

b.

Latin

c.

Scots

The correct answer is c.

a.

English

b.

Latin

c.

Scots

The correct answer is c.

a.

English

b.

Latin

c.

Scots

The correct answer is a.

a.

English

b.

Latin

c.

Scots

The correct answer is b.

In this next activity you will identify the most important factual information from this section.

Activity 6

Which of these statements are true and which are false according to the information given in the course text above?

a.

True

b.

False

The correct answer is b.

Answer

False – It was John Kyllor, a friar and member of the clergy himself, who was burnt at the stake in Edinburgh.

a.

True

b.

False

The correct answer is a.

a.

True

b.

False

The correct answer is b.

Answer

False – As censorship of plays was abolished in 1968, the Lord Chamberlain acted as theatre censor between 1737 and 1968.

a.

True

b.

False

The correct answer is a.

a.

True

b.

False

The correct answer is b.

Answer

False – The schoolchildren were required to perform for Kirk Sessions and local bigwigs, not least to practise their public speaking skills.

a.

True

b.

False

The correct answer is b.

Answer

False - The professional playhouse came to prominence during the 18th century and was well established at the end of that century.

a.

True

b.

False

The correct answer is b.

Answer

False – These plays toured Scotland as well

a.

True

b.

False

The correct answer is a.

9.2 Scots in drama since the 1900s

This section will draw your attention to the development of Scots language drama since the beginning of the 20th century.

By the end of the 19th century, Scotland-produced theatre was diminished – outside of variety and pantomime – by the professional theatre’s increased ‘industrialisation’. The mid-19th century railway revolution facilitated the development of a touring system focused on London’s West End, even though one of the major managements, Howard and Wyndham’s, had its headquarters in Edinburgh. This system was designed to develop and exploit scripts in versions of Standard English, with ‘regional’ accents reserved for minor or comic parts.

It was not that Scottish playwrights were excluded by this system – one of its mainstays at the beginning of the 20th century was J. M. Barrie. To succeed, however, dramatists had, like Barrie, to adjust their language and creative ideas to a British market in which Scots language dialogue was non-standard and, outside of ‘character’ parts, generally avoided.

The one major exception to this was Graham Moffat’s Bunty pulls the strings (1911), a West End success that ran for over 600 performances, opened in parallel in the same year on Broadway and at once toured the United States. The play, written in Scots, appeared to have no difficulty in reception by non-Scottish audiences. Yet, when he published the script, Moffat translated it into English, leaving only a few Scots words.

One can only speculate about his motivation – the play continued to play on tour in Scots – but it may be that there were some commercial doubts that a Scots language publication would be well-received.

Whatever Moffat’s reasons, Joe Corrie, a Fife miner, who began his playwriting career in the 1920s in a semi-professional context with his local Bowhill Players, wrote dynamic, politically committed plays in Scots about the people he lived amongst. The lively dialogue of In Time o Strife (1927), for example, explores industrial and domestic tensions surrounding the 1926 General Strike.

In the same decade, two other initiatives encouraged writing in Scots. One was the semi-professional Scottish National Players (1921-47) which toured plays on Scottish themes; the other was the amateur Scottish Community Drama Association (SCDA) founded in 1926 and still going strong. What marked all three developments was their ignoring, or even rejection as irrelevant to their concerns, of the commercial touring system.

Their concerns were with matters of direct interest to their audiences in Scotland. Corrie himself by the 1930s was writing for Sottish Community Drama Association companies, having developed a line in lighter comic plots.

Activity 7

To develop an idea of Joe Corrie’s bitingly critical political commentary at the heart of all his writing, you will read one of his poems telling the story of the miner Rebel Tam who became a complacent politician.

Part 2

Now practise your spoken Scots again by performing the poem or reading it out loud. Listen to our model, then record yourself and finally compare your version with our model.

Transcript

Listen

When Rebel Tam was in the pit

He tholed the very pangs o' Hell

In fectin' for the Richts o' Man,

And ga'e nae thoucht unto himsel'.

'If I was just in Parliament,

By God!' he vowed, ‘They soon would hear

The trumpet-ca' o' Revolution

Blastin' in their ear!'

Noo he is there, back-bencher Tam,

And listens daily to the farce

O' Tweeledum and Tweedledee,

And never rises off his arse.

Model

When Rebel Tam was in the pit

He tholed the very pangs o' Hell

In fectin' for the Richts o' Man,

And ga'e nae thoucht unto himsel'.

'If I was just in Parliament,

By God!' he vowed, ‘They soon would hear

The trumpet-ca' o' Revolution

Blastin' in their ear!'

Noo he is there, back-bencher Tam,

And listens daily to the farce

O' Tweeledum and Tweedledee,

And never rises off his arse.

Part 3

Although the text you have engaged with is a poem, it provides a good insight into the style of Corrie’s political satire and commentary. Read the poem again and this time highlight words and phrases which you think express the satire in his text.

Also, look for other features in the poem that make it very expressive. You might want to consider the structure of the poem as well, i.e. what each of the three verses tells us about Tam and in what way.

Discussion

The poem uses strong images that are painted with words and underlined by the use of Scots language. For example the phrase tholed the very pangs o’ Hell has a Biblical association to underline the intensity of the suffering endured by Tam the miner. A similarly compelling image painted with words is Tam’s vow that the trumpet-ca' o' Revolution would be ‘Blastin' in their ear!', which is a vivid illustration of the strong voice and impact Tam thinks he could have on Parliament as an MP.

The story told through these vivid images comes to a close and takes a sudden turn in the third verse where the reality of Tam’s role as an MP is that he merely listens… to the farce O’ Tweedledum and Tweedledee, showing the disrespect for politicians who are far removed from the reality of the lives of the people they are claiming to represent. The reference to the two identical characters from Lewis Carroll’s 'Alice in Wonderland' story underlines the derogatory commentary, as these two names have become equivalent for any two people who look and act in identical ways and have no minds of their own.

The very last word of the poem underlines the disdain for Tam through the use of a pejorative term for his backside, and the phrase rise off one’s arse links back to verse one in which Tam tirelessly fights for the workers’ rights and which shows how far Tam has moved away from what he fought for in the past.

The naming of the poem’s protagonist is satire in itself. We hear about Rebel Tam, which clearly is a degradation, as the poem undoubtedly highlights that Tam has become anything but a Rebel.

Through the use of direct speech in the second verse of the poem effectively counter-poses what Tam promises his potential voters and then the third verse shows the reality of this promise.

9.3 Scots language drama after 1940

The political drive associated with writing in Scots seemed to be fading when in 1941 Glasgow's Unity theatre company was formed by amalgamation of five radical amateur theatre companies. From the first, the company’s work included Scots versions of theatre classics, but, when it formed a professional company after the war, it produced more original work in Scots, some of the highest calibre.

One example of this is Ena Lamont Stewart’s Men Should Weep (1947), recognised, after a revival by 7:84 Theatre Company in 1982 and revivals by London’s National Theatre in 2010 and the Scottish National Theatre in 2011, as a masterpiece. Unity also premièred Robert McLellan’s The Flouers of Edinburgh in 1948, a period play exploring tensions as English began to be seen in Enlightenment Edinburgh as a more ‘polite’ language than Scots.

McLellan had begun in 1933 writing Scots language one-act plays in a somewhat sentimentalised and misogynistic version of rural Scottish conflicts, especially in the sixteenth-century Borders. After his dramatically more thoughtful Jamie The Saxt (1937), he returned to this demanding series of plays, but The Flouers of Edinburgh marked a new stage in his writing, exploring profound issues of national identity, including language, in vibrant Scots dialogue. The Flouers of Edinburgh was complemented by the 1948 revival of a version of Lindsay’s masterpiece, The Thrie Estaitis, in Robert Kemp’s bowdlerised version.

What the pioneers of the 1920s, the Glasgow Unity writers, McLellan and Lindsay (via Kemp) stimulated was a recognition that Scots was a lively language for the stage, sophisticated and available for political activism, and that audiences loved hearing it spoken. Alexander Reid, McLellan’s contemporary, wrote in 1958 in a preface to his Two Scots Plays:

If we are to fulfil our hope that Scotland may some day make a contribution to World Drama […] we can only do so by cherishing, not repressing our national peculiarities (including our language), though whether a Scottish national drama, if it comes to birth, will be written in Braid Scots or the speech, redeemed for literary purposes, of Argyle Street, Glasgow, or the Kirkgate, Leith, is anyone's guess.

During the 1960s, it seemed as if the energy of Scots language drama was under threat. Unity had closed in 1951. McLellan seemed isolated and focused on historical themes. Other attempts at Scots language drama like Sydney Goodsir Smith’s The Wallace (1960) – with the exception of John Arden’s Armstrong’s Last Goodnight (1964) – were stilted, static and backward-looking.

In the 1970s, however, growing out of the work of earlier playwrights and their experiments, and using the demotic Scots of ‘Argyle Street, Glasgow, or the Kirkgate, Leith’, usually in a way Reid would not have thought ‘redeemed’, a new generation emerged. This revitalised the use of Scots on stage in a way that continues to this day. Highlights of such work in the 1970s include Bill Bryden’s Willie Rough (1972), Tom McGrath’s The Hard Man (1977) and John Byrne’s Slab Boys trilogy (1978-82).

Since then, Scots language drama has shown itself capable of dealing with a wide range of important topics, whether issues of national and gender stereotypes in Liz Lochhead’s Mary Queen of Scots got her head chopped off (1987), class and gender oppression in Sue Glover’s Bondagers (1991) or issues of military life and the Iraq War in Gregory Burke’s Black Watch (2006).

Activity 8

This activity is designed to help you summarize the key information about Scots language drama after 1940.

Match the listed qualities of Scots language plays with the eras in which they were written and performed according to the information in the text.

a.

1940s and 50s

b.

1960s

c.

1970s

d.

1980s - early 21st century

The correct answer is a.

a.

1940s and 50s

b.

1960s

c.

1970s

d.

1980s - early 21st century

The correct answer is c.

a.

1940s and 50s

b.

1960s

c.

1970s

d.

1980s - early 21st century

The correct answer is b.

a.

1940s and 50s

b.

1960s

c.

1970s

d.

1980s - early 21st century

The correct answer is d.

a.

1940s and 50s

b.

1960s

c.

1970s

d.

1980s - early 21st century

The correct answer is b.

a.

1940s and 50s

b.

1960s

c.

1970s

d.

1980s - early 21st century

The correct answer is a.

a.

1940s and 50s

b.

1960s

c.

1970s

d.

1980s - early 21st century

The correct answer is d.

a.

1940s and 50s

b.

1960s

c.

1970s

d.

1980s - early 21st century

The correct answer is a.

a.

1940s and 50s

b.

1960s

c.

1970s

d.

1980s - early 21st century

The correct answer is d.

a.

1940s and 50s

b.

1960s

c.

1970s

d.

1980s - early 21st century

The correct answer is a.

9.4 Scots in television drama

In this section, you are going to focus on examples of the use of Scots in television drama, including comedy. You may either be familiar with the most recent examples mentioned, and other examples can also be found online, usually, on YouTube, in case you are interested in watching these following your study of this unit.

When radio broadcasting started in Britain in October 1922 it was very much Londoncentric: its language and accents were clearly those of middle- and upper-class England. In March 1939, on the BBC Scottish Home Service, Helen W. Pryde’s series based on a working-class Glasgow family, The McFlannels, broke through and ran intermittently until 1953. Some episodes are available on YouTube and reveal character-based Scots dialogue ranging from strong Glaswegian-Scots dialect through to Scottish Standard English.

The programme was popular in Scotland although towards the end it was seen by many as becoming stale. An attempt to transfer it to television in 1958 proved fruitless: characters so much in the mind’s eye did not seem ‘real’ on the screen. Nonetheless, the programme’s powerful Scots language dialogue’s initial success breached pre-war BBC emphasis on Received Pronunciation and Standard English.

When television arrived in Scotland in 1952 there was still no strong impetus for Scots language television drama. Key programmes were often London-based, including soaps like The Grove Family (1954-57) or Dixon of Dock Green (1955-76). Possibly the first major series using Scots language dialogue (though not very emphatically) was Para Handy – Master Mariner (1959-60), based on Neil Munro’s characters. The series was revived, slightly recast, in the 1960s.

Meantime, television borrowed forms of comedy from variety. Stanley Baxter, for one, developed in the mid-1960s a series of televised sketches parodying stiff televised language lessons with his Parliamo Glasgow. Here, for the uninitiated, he interpreted such phrases as sanoffy as in sanoffy caul day or takyurhonaffmabum, a demand to cease over-familiarity. Such joyous transcription of Scots-Glasgow dialect is reflected in several later poems by Tom Leonard, but, televised, they introduced a celebration of spoken Scots much appreciated in Scotland, if not entirely understood south of the Border.

![]()

Try to tune into Glasgow Scots by watching an example of Baxter’s Parliamo Glasgow ‘language lessons’. This one is called ‘Upatra Burd’s’.

Activity 9

Part 1

Read the phrases out loud and then match them with their English equivalents.

You parliamo Glasgow? (updated for Polish bus drivers).

Using the following two lists, match each numbered item with the correct letter.

Wan and three weans to Scotstoun

Wan tae the Croass

Gie's a hon wi the messages

Wharlla stick ma wean's buggie?

Awayyego, it's nivir that dear!

a.Please give me a hand with my groceries

b.Where will I put my child's pushchair?

c.No, it can't be that expensive!

d.A single to Charing/Anniesland etc. Cross

e.A single and three halves to Scotstoun

- 1 = e

- 2 = d

- 3 = a

- 4 = b

- 5 = c

Part 2

Now listen to the phrases by a Scots speaker and record yourself saying them. Then compare your pronunciation with our model.

Transcript

Listen

Wan and three weans to Scotstoun.

Wan tae the Croass.

Gie's a hon wi the messages.

Wharlla stick ma wean's buggie?

Awayyego, it's nivir that dear!

Model

Wan and three weans to Scotstoun.

Wan tae the Croass.

Gie's a hon wi the messages.

Wharlla stick ma wean's buggie?

Awayyego, it's nivir that dear!

Gradually, confidence to develop a variety of televised applications, both short-form comic and long-form dramatic, of Scots language developed. By the 1970s it took off. The 1971 BBC adaptation of Sunset Song was highly regarded and, while its Scots was somewhat diluted, it was still seen as difficult to understand.beyond Scotland.

In the next year, Peter McDougall, employing uncompromising Scots language dialogue in Just Your Luck, initiated his series over the next three decades of key Scots language dramas for the BBC, often dealing with contemporary sectarian issues and set in or near his native Greenock.

The potential of Scots as a serious televised dramatic language was established.

While such a series as Taggart, launched by STV in 1983, is much parodied and often derided, its role in bringing, if not fully developed Scots, a Scots patois into the mainstream of detective soap should not be scorned. While later in the 1980s John Byrne, whose use of Scots on stage has already been mentioned, wrote two emotionally powerful Scots language series, Tutti Frutti (1987) and Your Cheatin’ Heart (1990), that achieved popular acclaim beyond Scotland.

Though there is a tendency for Scots on television still to be used in comedy drama, often Scots-speaking writers use it there subversively. Ian Pattison’s series Rab C Nesbitt (1990-2014) used Glaswegian-Scots to blackly comic and often social satirical effect. Alan Cumming and Forbes Masson in their spoof air-line series The High Life (1994-5) wrote apparently in Scottish Standard English but smuggled in many Scots language jokes.

For example, calling a bitter old rock star Guy Wersh and several times using the rudest Scots word of female genitals, fud, before the watershed, presumably as an inside-joke against the monolingual English-speaking producers who would never have allowed the English equivalent.

The use of Scots is now accepted generally, despite occasional resistance by monolingual English-speaking audiences. In 2014, Brian Cox acting in the BBC series Shetland, when he ‘reckoned he had learned the Shetland tongue “pretty well” for his character Magnus Bain’, was asked to re-record his lines because of fears that viewers would not understand.

Nonetheless, alongside serious drama on Scottish and UK-wide television, comedy extravaganzas like Chewin’ the Fat (1999-2005) and its spin-off Still Game (since 2002), Burnistoun (2009-12) and Gary: Tank Commander (2009-12) have consistently employed Scots to subversive, witty and often surreal effect, while River City (since 2002), created by Stephen Greenhorn, employs a naturalistically varied range of Scots dialects in the context of a long-running soap.

Such a variety of use of Scots, however at times tempered for consumption beyond Scotland, would have been unthinkable in pre-war broadcasting.

Activity 10

In this activity you will summarise the most important changes in the way in which Scots language was used in broadcasting from around 1940s, which expose shifting attitudes and a marked difference to pre-war broadcasting.

Part 1

Match the changes around the use of Scots language with the programmes that achieved these changes according to the information given in the text.

Using the following two lists, match each numbered item with the correct letter.

H. W. Pryde – The McFlannels

S. Baxter – Parliamo Glasgow

Peter McDougall – Just Your Luck

Glen Chandler et al. – Taggart

John Byrne – Tutti Frutti, Cheatin’ Heart

Ian Patterson – Rab C Nesbitt

Chewin’ the Fat, Still Game, Burnistoun and Gary: Tank Commander

a.Parodied stiff televised language lessons using Scots

b.Brought emotionally powerful elements to Scots language series

c.Used Glaswegian-Scots to blackly comic and often social satirical effect

d.Brought Scots patois into the mainstream of detective soap

e.Breached pre-war BBC emphasis on Received Pronunciation and Standard English

f.Used uncompromising Scots language dialogue in serious dramatic language

g.Employed Scots to subversive, witty and often surreal effect

- 1 = e

- 2 = a

- 3 = f

- 4 = d

- 5 = b

- 6 = c

- 7 = g

9.5 Scots in film

The ways in which Scots appears in films might, on the face of it, be expected to parallel the ways it has developed in television drama. In fact, the very different structures of the television and film industries as businesses mean that the history of Scots in each is quite distinct.

Activity 11

When reading this section, note points which are of interest to you for reflection at the end of the unit, such as:

The use of Scots language in film has a far patchier record than its use on stage and even on television. Arguably there are a number of reasons for this including the fact that:

Scotland has no established native film production industry

the Scottish population is too small to offer a lucrative market for Scots language films

film producers lay emphasis on international sales in markets where English is a lingua franca.

A further reason may be that often the versions of ‘Scotland’ presented in film are romanticised, sentimentalise its people and history or indulge in ‘tartanry’ or ‘Highlandism’. Hence, for example, the use in Braveheart (1995) of tartan and face paint in a manner entirely historically inaccurate, while, despite several of the cast being Scots, the variable accents of its ‘Scottish’ characters reflect valiant, but often failed, attempts by non-Scots – and a non-Scot wrote the script in English.

In other words, the structures of the film industry militate against easy inclusion of Scots in film dialogue.

(This is a poster advertising the 1949 Whisky Galore film for a Swedish Audience, which features a mix of a cartoon characters in kilts and black-and-white photographs of the actors.)

Older films set in Scotland, like I know where I’m going (1945) do not use Scots at all, but simply seek to employ Scottish accents. The same is true even of films like Alexander Mackendrick’s original Whisky Galore (1949), which, while it employed many fine Scottish actors, never sought to use the Scots language. Both these classics were produced by non-Scottish production companies, the former by Powell and Pressburger and the latter by Ealing Studios.

The more recent development of interest by producers with an understanding of Scottish culture may not have completely altered the position, but television companies, perhaps out of their growing experience of Scots language in television production, began in the 1970s and after to take more ‘risks’ in supporting films in which Scots was to varying extents heard more. Bill Forsyth’s Gregory’s Girl (1980), for example, while making limited use of Scots dialogue, achieved international success.

Arguably, it is from the 1990s onwards that Scots features more actively in film, following the worldwide impact of Trainspotting with its vibrant use of Edinburgh-Scots dialect. As mentioned in the Dialect Diversity unit, the film Trainspotting was subtitled in other countries – even in countries like the U.S.A. where English is spoken as a first language – while the Pixar film Brave featured a distinctly Doric-speaking character who was not subtitled, but it is apparent that the character is supposed to be difficult to understand to suit comic purposes.

Activity 12

In this activity you are working with an extract from Irvine Welsh’s novel Trainspotting, trying to ‘tune’ into Leith, a part of Edinburgh, Scots and then speaking it yourself. Do be alerted to the characteristic of Welsh’s style of writing - the frequent use of strong swear words.

A number of highly-regarded films, though certainly not many, have since then employed Scots language dialogues, including My Name is Joe (1998), Sweet Sixteen (2002), Red Road (2006) and The Angels’ Share (2012). The first two and the last of these films were directed by the radical director Ken Loach and all, like Trainspotting, were in part funded by either the BBC, Film Four or the British Film Institute.

In short, Scots language is more likely to be heard in film when the producers have an interest in Scottish culture, a public film body is involved in providing a key element of financial support and the themes are in one way or another radical.

![]()

What do you think: Since Scots is a distinct language from English, though very close to it, should subtitles be used for Scots dialogue in internationally-marketed films?

9.6 What I have learned

The different histories of the use of Scots language in drama, television and film highlight the importance of cultural context, economic and industrial structures, thematic content and likely audience in affecting the extent to which Scots language is employed in dialogue.

In assessing the prevalence of the use of Scots, it is important to recognise that it is not only cultural matters, narrowly defined as artistic considerations, that have an impact. It is important to understand that in a broader definition of the word ‘culture’ politics, economics, ethics and industrial organisations as well as values express and shape the broader social values that go to make up any given culture.

Given this, the place of Scots language in drama, television and film is affected not only by the nature of Scots as a language, but the perceptions of writers, directors, and producers, not to mention the audience, of the role of Scotland, its language and artistic culture within that larger definition of culture, not to mention the framework of the specific production culture of each of the art forms of theatre, television and film.

The final activity of this section is designed to help you review, consolidate and reflect on what you have learned in this unit. You will revisit the key learning points of the unit and the initial thoughts you noted down before commencing your study of it.

Activity 13

Before finishing your work on this unit, please revisit what you worked on in Activity 1, where we asked you to take some notes on what you already knew in relation to the key learning points of the unit.

Compare your notes from before you studied this unit with what you have learned here and add to these notes as you see fit to produce a record of your learning.

Here are the key learning points again for you as a reminder:

The history of Scots as a stage language from the 16th century onwards

Scots language drama over the 20th century

Developments in the use of Scots in television drama

Scots language in film

Underlying issues affecting the use of Scots in dramatic performance-writing

Further research

BBC Bitesize, ‘Men Should Weep’ by Ena Lamont Stewart, provides an in-depth study of the play, its background, characters, plot and themes with useful learning resources and information about the author.

This clip encompasses interviews with the cast of the National Theatre of Scotland on their roles in the performance of Lamont Stewart’s ‘Men Should Weep’.

Now go on to Unit 10: Scots and work.

References

Acknowledgements

Every effort has been made to contact copyright holders. If any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources:

Course Image: Supplied by Bruce Eunson / Education Scotland

Activity 3 image: © National Museums Scotland

Activity 4 image: Taken from http://www.dsl.ac.uk/results/fleg

image on page 11: Andrew Shiva. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution Licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0

Image on page 12: Bubobubo2. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike Licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/

Left hand image on page 13: © The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images

Right hand image on page 13: George Buchanan after Arnold Bronckorst, oil on panel, 1581, NPG 524. © National Portrait Gallery, London

Image on page 27: Used with permission of Nordicposters.com

Text

Poem in Activity 7: Corrie, J. (1932) Rebel Tam. Used with permission