What do you think?

Rate this book

247 pages, Mass Market Paperback

First published January 1, 1940

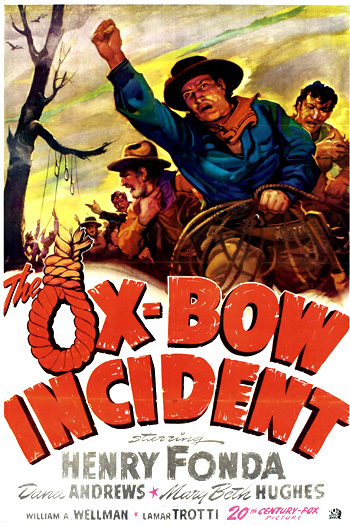

unwavering choice for the year’s finest first novel. It has many of the elements of an old-fashioned horse opera – monosyllabic cowpunchers, cattle rustlers, a Mae West lady, barroom brawls, shootings, lynchings, a villainous Mexican. But it bears about the same relation to an ordinary western that The Maltese Falcon does to a hack detective story. Not to put a fine point on it, I think it’s sort of what you might call a masterpiece.