Rightly considered one of cinema’s greatest paranoid thrillers, John Frankenheimer’s 1962 classic The Manchurian Candidate is a film that remains hugely engaging – and surprisingly topical. Adapted from Richard Condon’s novel of the same name, its famous title lingers in the zeitgeist, still used to speculate on puppet-mastering foreign powers and their political influence.

The film opens with the Medal of Honor being awarded to Sergeant Raymond Shaw (Laurence Harvey) for his service in the Korean war. Shaw returns home to a rousing reception, but isn’t a real hero: the Sergeant and the rest of his platoon were brainwashed into believing he saved their lives during combat. Installed as a sleeper agent, a hypnotised Shaw can do the dirty work of communists, activated by the sight of a playing card: the queen of diamonds.

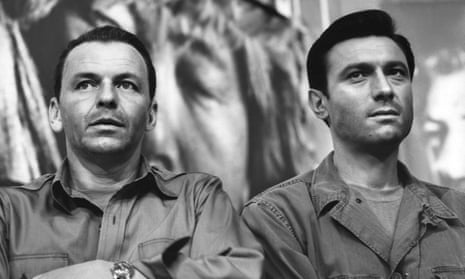

Controlling Shaw is part of an intricate scheme orchestrated by villains including Eleanor Iselin (Angela Lansbury, delivering a classic performance), who is secretly working to turn the US government into an authoritarian regime while masterminding her senator husband’s vice-presidential bid. Not everyone submits so easily, though: the film’s protagonist, Major Bennett Marco (Frank Sinatra), senses something is up, suffering from an intense recurring dream – “a real swinger of a nightmare”.

The visualisation of this nightmare forms the film’s unforgettable sequence: a surreal space where the American soldiers appear to be at a meeting of a New Jersey ladies’ garden club. They’re actually sitting, totally brainwashed, in front of a congregation of communist scientists. Frankenheimer blends these mixed realities together in hallucinogenic ways, such as showing a well-dressed woman addressing the club, then a spooky smooth-scalped scientist in her place.

All this might sound like a preposterous example of McCarthyism on steroids, but it’s executed so well you barely even notice the silliness of it. Sinatra’s frazzled performance is key to film’s success, skilfully illustrating the protagonist’s ravaged mindset and imbuing the drama with red-hot intensity. “There’s something phony about me, about Raymond Shaw, about the whole Medal of Honor business,” Marco says, embroiled in a mystery without knowing what the mystery even is, let alone how to solve it.

The film has an uncomfortably edgy aesthetic, infusing what might have been a handsome monochrome look with off-kilter effects – including odd camera angles and blurry elements. Frankenheimer received praise in particular for an out-of-focus shot of Sinatra, with critics suggesting he was using a distorted camera lens to illustrate a disoriented mindset – only for the director to later explain this was unintentional and he was working with the best he had.

If the premise were played out today, Shaw wouldn’t be activated by a playing card – instead, maybe, an app on his phone or an implant in his brain (as was the case in a decent, workmanlike remake released in 2004, with Denzel Washington in Sinatra’s role). But that’s one of the least interesting examples of how the contemporary world differs from the one imagined in the film. If the Kremlin wanted to interfere with an American election these days, they could simply spread online misinformation to do the dirty work for them.

The villains in Frankenheimer’s film go to drastic lengths, planning to exploit a political assassination (executed by the brainwashed Shaw) and, in the subsequent chaos, usher in an authoritarian regime – by “rallying a nation of viewers to hysteria”, as they put it. This seems almost quaint today: you don’t need extraordinary circumstances to rally Americans into hysteria; just a microphone and media coverage.

While the term “The Manchurian Candidate” might not resonate all that much with younger generations, the film – despite being rooted in a very particular political context – has a degree of metaphoric malleability. Most importantly, perhaps, it’s very finely crafted, with only a few flat scenes en route to an unforgettable finale.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion