- Information

- AI Chat

Gothic Extracts Booklet

English Literature

Sixth Form (A Levels)

• A2 - A LevelRecommended for you

Preview text

OCR

A2 English Literature

Gothic Extracts

Contents

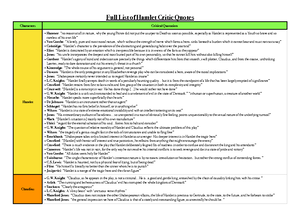

- The Castle of Otranto – Extract Extract Year Page

- The Castle of Otranto – Extract

- The Romance of the Forest

- The Mysteries of Adolpho - Vol. 2 Chap.

- The Mysteries of Adolpho - Vol. 2 Chap.

- The Monk – Chapter

- The Monk – Chapter

- The Italian

- Northanger Abbey

- Frankenstein

- Nightmare Abbey

- A Night in the Catacombs

- The Tell-Tale Heart

- Wuthering Heights

- Varney the Vampire

- Carmilla

- The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll & Mr Hyde

- The Picture of Dorian Gray

- The Yellow Wallpaper

- The Time Machine

- Dracula – Extract

- Dracula – Extract

- The Eyes of a Panther

- The Hound of the Baskervilles

- The Treasure of Abbot Thomas

- The Ghosts

- Light in August

- Rebecca

- Outer Dark

- Interview with the Vampire

- The Lady of the House of Love

- The Woman in Black

- The Wasp Factory

what, he advanced hastily – But what a sight for a father’s eyes! – He beheld his child dashed to pieces, and almost buried under an enormous helmet, an hundred times more large than any casque ever made for human being, and shaded with a proportionable quantity of black feathers. The Castle of Otranto - 1764 - Horace Walpole – Extract 2 As it was now evening, the servant who conducted Isabella bore a torch before her. When they came to Manfred, who was walking impatiently about the gallery, he started and said hastily, "Take away that light, and begone." Then shutting the door impetuously, he flung himself upon a bench against the wall, and bade Isabella sit by him. She obeyed trembling. "I sent for you, lady," said he, — and then stopped under great appearance of confusion. "My lord!" — "Yes, I sent for you on a matter of great moment," resumed he, — "Dry your tears, young lady — you have lost your bridegroom. — Yes, cruel fate! and I have lost the hopes of my race! — but Conrad was not worthy of your beauty." — "How! my lord," said Isabella; "sure you do not suspect me of not feeling the concern I ought. My duty and affection would have always — " "Think no more of him," interrupted Manfred; "he was a sickly puny child, and heaven has perhaps taken him away that I might not trust the honours of my house on so frail a foundation. The line of Manfred calls for numerous supports. My foolish fondness for that boy blinded the eyes of my prudence — but it is better as it is. I hope in a few years to have reason to rejoice at the death of Conrad." Words cannot paint the astonishment of Isabella. At first she apprehended that grief had disordered Manfred's understanding. Her next thought suggested that this strange discourse was designed to ensnare her: she feared that Manfred had perceived her indifference for his son: and in consequence of that idea she replied, "Good my lord, do not doubt my tenderness: my heart would have accompanied my hand. Conrad would have engrossed all my care; and wherever fate shall dispose of me, I shall always cherish his memory, and regard your highness and the virtuous Hippolita as my parents." "Curse on Hippolita!" cried Manfred: "forget her from this moment as I do. In short, lady, you have missed a husband undeserving of your charms: they shall now be better disposed of. Instead of a sickly boy, you shall have a husband in the prime of his age, who will know how to value your beauties, and who may expect a numerous offspring." "Alas! my lord," said Isabella, "my mind is too sadly engrossed by the recent catastrophe in your family to think of another marriage. If ever my father returns, and it shall be his pleasure, I shall obey, as I did when I consented to give my hand to your son: but until his return, permit me to remain under your hospitable roof, and employ the melancholy hours in assuaging yours, Hippolita's, and the fair Matilda's affliction." "I desired you once before," said Manfred angrily, "not to name that woman: from this hour she must be a stranger to you, as she must be to me; — in short, Isabella, since I cannot give you my son, I offer you myself." — "Heavens!" cried Isabella, waking from her delusion, "what do I hear! You! My lord! You! My father-in-law! the father of Conrad! the husband of the virtuous and tender Hippolita!" — "I tell you," said Manfred imperiously, "Hippolita is no longer my wife; I divorce her from this hour. Too long has she cursed me by her unfruitfulness: my fate depends on having sons, — and this night I trust will give a new date to my hopes." At those words he seized the cold hand of Isabella, who was half-dead with fright and horror. She shrieked and started from him. Manfred rose to pursue her, when the moon, which was now up and gleamed in at the opposite casement, presented to his sight the plumes of the fatal helmet, which rose to the height of the windows, waving backwards and forwards in a tempestuous manner, and accompanied with a hollow and rustling sound. Isabella, who gathered courage from her situation, and who dreaded nothing so much as Manfred's pursuit of his declaration, cried, "Look! my lord; see, heaven itself declares against your impious intentions!" — "Heaven nor hell shall impede my designs," said Manfred, advancing again to seize the princess. At that instant the portrait of his grandfather, which hung over the bench where they had been sitting, uttered a deep sigh, and heaved its breast. Isabella, whose back was turned to the picture, saw not the motion, nor knew whence the sound came, but started, and said, "Hark, my lord! What sound was that?" and at the same time made towards the door. Manfred, distracted between the flight of Isabella, who had now reached the stairs, and yet unable to keep his eyes from the picture, which began to move, had however advanced some steps after her, still looking backwards on the portrait, when he saw it quit its panel, and descend on the floor with a grave and melancholy air. "Do I dream?" cried Manfred returning, "or are the devils themselves in league against me? Speak, infernal spectre! or, if thou art my grandsire, why dost thou too conspire against thy wretched descendant, who too dearly pays for — " Ere he could finish the sentence the vision sighed again, and made a sign to Manfred to follow him. "Lead on!" cried Manfred; "I will follow thee to the gulph of perdition." The spectre marched sedately, but dejected, to the end of the gallery, and turned into a chamber on the

right hand. Manfred accompanied him at a little distance, full of anxiety and horror, but resolved. As he would have entered the chamber, the door was clapped to with violence by an invisible hand. The prince, collecting courage from this delay, would have forcibly burst open the door with his foot, but found that it resisted his utmost efforts. "Since hell will not satisfy my curiosity," said Manfred, "I will use the human means in my power for preserving my race; Isabella shall not escape me." That lady, whose resolution had given way to terror the moment she had quitted Manfred, continued her flight to the bottom of the principal staircase. There she stopped, not knowing whither to direct her steps, nor how to escape from the impetuosity of the prince. The gates of the castle she knew were locked, and guards placed in the court. Should she, as her heart prompted her, go and prepare Hippolita for the cruel destiny that awaited her, she did not doubt but Manfred would seek her there, and that his violence would incite him to double the injury he meditated, without leaving room for them to avoid the impetuosity of his passions. Delay might give him time to reflect on the horrid measures he had conceived, or produce some circumstance in her favour, if she could for that night at least avoid his odious purpose. — Yet where conceal herself? how avoid the pursuit he would infallibly make throughout the castle? As these thoughts passed rapidly through her mind, she recollected a subterraneous passage which led from the vaults of the castle to the church of St. Nicholas. Could she reach the altar before she was overtaken, she knew even Manfred's violence would not dare to profane the sacredness of the place; and she determined, if no other means of deliverance offered, to shut herself up for ever among the holy virgins, whose convent was contiguous to the cathedral. In this resolution, she seized a lamp that burned at the foot of the staircase, and hurried towards the secret passage. The lower part of the castle was hollowed into several intricate cloisters; and it was not easy for one under so much anxiety to find the door that opened into the cavern. An awful silence reigned throughout those subterraneous regions, except now and then some blasts of wind that shook the doors she had passed, and which, grating on the rusty hinges, were re-echoed through that long labyrinth of darkness. Every murmur struck her with new terror; — yet more she dreaded to hear the wrathful voice of Manfred urging his domestics to pursue her. She trod as softly as impatience would give her leave, — yet frequently stopped and listened to hear if she was followed. In one of those moments she thought she heard a sigh. She shuddered, and recoiled a few paces. In a moment she thought she heard the step of some person. Her blood curdled; she concluded it was Manfred. Every suggestion that horror could inspire rushed into her mind. She condemned her rash flight, which had thus exposed her to his rage in a place where her cries were not likely to draw anybody to her assistance. — Yet the sound seemed not to come from behind, — if Manfred knew where she was, he must have followed her: she was still in one of the cloisters, and the steps she had heard were too distinct to proceed from the way she had come. Cheered with this reflection, and hoping to find a friend in whoever was not the prince, she was going to advance, when a door that stood ajar, at some distance to the left, was opened gently: but ere her lamp, which she held up, could discover who opened it, the person retreated precipitately on seeing the light. Isabella, whom every incident was sufficient to dismay, hesitated whether she should proceed. Her dread of Manfred soon outweighed every other terror. The very circumstance of the person avoiding her gave her a sort of courage. It could only be, she thought, some domestic belonging to the castle. Her gentleness had never raised her an enemy, and conscious innocence bade her hope that, unless sent by the prince's order to seek her, his servants would rather assist than prevent her flight. Fortifying herself with these reflections, and believing, by what she could observe, that she was near the mouth of the subterraneous cavern, she approached the door that had been opened; but a sudden gust of wind that met her at the door extinguished her lamp, and left her in total darkness. Words cannot paint the horror of the princess's situation. Alone in so dismal a place, her mind imprinted with all the terrible events of the day, hopeless of escaping, expecting every moment the arrival of Manfred, and far from tranquil on knowing she was within reach of somebody, she knew not whom, who for some cause seemed concealed thereabouts, — all these thoughts crowded on her distracted mind, and she was ready to sink under her apprehensions. She addressed herself to every saint in heaven, and inwardly implored their assistance. For a considerable time she remained in an agony of despair. At last, as softly as was possible, she felt for the door, and, having found it, entered trembling into the vault from whence she had heard the sigh and steps. It gave her a kind of momentary joy to perceive an imperfect ray of clouded moonshine gleam from the roof of the vault, which seemed to be fallen in, and from whence hung a fragment of earth or building, she could not distinguish which, that appeared to have been crushed inwards. She advanced eagerly towards this chasm, when she discerned a human form standing close against the wall. She shrieked, believing it the ghost of her betrothed Conrad.

Shocked and surprised, she looked round the room for some object that might confirm or destroy the dreadful suspicion which now rushed upon her mind; but she saw only a great chair, with broken arms, that stood in one corner of the room, and a table in a condition equally shattered, except that in another part lay a confused heap of things, which appeared to be old lumber. She went up to it, and perceived a broken bedstead, with some decayed remnants of furniture, covered with dust and cobwebs, and which seemed, indeed, as if they had not been moved for many years. Desirous, however, of examining farther, she attempted to raise what appeared to have been part of the bedstead, but it slipped from her hand, and, rolling to the floor, brought with it some of the remaining lumber. Adeline started aside and saved herself, and when the noise it made had ceased, she heard a small rustling sound, and as she was about to leave the chamber, saw something falling gently among the lumber. It was a small roll of paper, tied with a string, and covered with dust. Adeline took it up, and on opening it perceived an handwriting. She attempted to read it, but the part of the manuscript she looked at was so much obliterated that she found this difficult, though what few words were legible impressed her with curiosity and terror, and induced her to return immediately to her chamber. The Mysteries of Adolpho - 1794 - Anne Radcliffe From Volume 2, Chapter 5 Towards the close of day, the road wound into a deep valley. Mountains, whose shaggy steeps appeared to be inaccessible, almost surrounded it. To the east, a vista opened, that exhibited the Apennines in their darkest horrors; and the long perspective of retiring summits, rising over each other, their ridges clothed with pines, exhibited a stronger image of grandeur, than any that Emily had yet seen. The sun had just sunk below the top of the mountains she was descending, whose long shadow stretched athwart the valley, but his sloping rays, shooting through an opening of the cliffs, touched with a yellow gleam the summits of the forest, that hung upon the opposite steeps, and streamed in full splendour upon the towers and battlements of a castle, that spread its extensive ramparts along the brow of a precipice above. The splendour of these illumined objects was heightened by the contrasted shade, which involved the valley below. "There," said Montoni, speaking for the first time in several hours, "is Udolpho." Emily gazed with melancholy awe upon the castle, which she understood to be Montoni's; for, though it was now lighted up by the setting sun, the gothic greatness of its features, and its mouldering walls of dark grey stone, rendered it a gloomy and sublime object. As she gazed, the light died away on its walls, leaving a melancholy purple tint, which spread deeper and deeper, as the thin vapour crept up the mountain, while the battlements above were still tipped with splendour. From those too, the rays soon faded, and the whole edifice was invested with the solemn duskiness of evening. Silent, lonely and sublime, it seemed to stand the sovereign of the scene, and to frown defiance on all who dared to invade its solitary reign. As the twilight deepened, its features became more awful in obscurity, and Emily continued to gaze, till its clustering towers were alone seen, rising over the tops of the woods, beneath whose thick shade the carriages soon after began to ascend. The extent and darkness of these tall woods awakened terrific images in her mind, and she almost expected to see banditti start up from under the trees. At length, the carriages emerged upon a heathy rock, and, soon after, reached the castle gates, where the deep tone of the portal bell, which was struck upon to give notice of their arrival, increased the fearful emotions that had assailed Emily. While they waited till the servant within should come to open the gates, she anxiously surveyed the edifice: but the gloom that overspread it allowed her to distinguish little more than a part of its outline, with the massy walls of the ramparts, and to know that it was vast, ancient and dreary. From the parts she saw, she judged of the heavy strength and extent of the whole. The gateway before her, leading into the courts, was of gigantic size, and was defended by two round towers, crowned by overhanging turrets, embattled, where instead of banners, now waved long grass and wild plants, that had taken root among the mouldering stones, and which seemed to sigh, as the breeze rolled past, over the desolation around them. The towers were united by a curtain, pierced and embattled also, below which appeared the pointed arch of an huge portcullis, surmounting the gates: from these, the walls of the ramparts extended to other towers, overlooking the precipice, whose shattered outline, appearing on a gleam that lingered in the west, told of the ravages of war. — Beyond these all was lost in the obscurity of evening. While Emily gazed with awe upon the scene, footsteps were heard within the gates, and the undrawing of the bolts; after which an ancient servant of the castle appeared, forcing back the huge folds of the portal, to admit his lord. As the carriage-wheels rolled heavily under the portcullis, Emily's heart sunk, and she seemed as if she was going into her prison; the gloomy court into which she passed served to confirm the idea, and her imagination, ever awake to circumstance, suggested even more terrors than her reason could justify.

Another gate delivered them into the second court, grass-grown, and more wild than the first, where, as she surveyed through the twilight its desolation — its lofty walls, overtopped with briony, moss and nightshade, and the embattled towers that rose above, — long-suffering and murder came to her thoughts. One of those instantaneous and unaccountable convictions, which sometimes conquer even strong minds, impressed her with its horror. The sentiment was not diminished when she entered an extensive gothic hall, obscured by the gloom of evening, which a light, glimmering at a distance through a long perspective of arches, only rendered more striking. As a servant brought the lamp nearer, partial gleams fell upon the pillars and the pointed arches, forming a strong contrast with their shadows, that stretched along the pavement and the walls. The Mysteries of Adolpho - 1794 - Anne Radcliffe Volume 2, Chapter 6 Emily took no further notice of the subject, and, after some struggle with imaginary fears, her good nature prevailed over them so far, that she dismissed Annette for the night. She then sat, musing upon her own circumstances and those of Madame Montoni, till her eye rested on the miniature picture which she had found, after her father's death, among the papers he had enjoined her to destroy. It was open upon the table, before her, among some loose drawings, having, with them, been taken out of a little box by Emily some hours before. The sight of it called up many interesting reflections, but the melancholy sweetness of the countenance soothed the emotions which these had occasioned. It was the same style of countenance as that of her late father, and, while she gazed on it with fondness on this account, she even fancied a resemblance in the features. But this tranquillity was suddenly interrupted, when she recollected the words in the manuscript that had been found with this picture, and which had formerly occasioned her so much doubt and horror. At length, she roused herself from the deep reverie into which this remembrance had thrown her; but, when she rose to undress, the silence and solitude to which she was left, at this midnight hour, for not even a distant sound was now heard, conspired with the impression the subject she had been considering had given to her mind, to appall her. Annette's hints, too, concerning this chamber, simple as they were, had not failed to affect her, since they followed a circumstance of peculiar horror which she herself had witnessed, and since the scene of this was a chamber nearly adjoining her own. The door of the stair-case was, perhaps, a subject of more reasonable alarm, and she now began to apprehend, such was the aptitude of her fears, that this stair-case had some private communication with the apartment which she shuddered even to remember. Determined not to undress, she lay down to sleep in her clothes, with her late father's dog, the faithful Manchon, at the foot of the bed, whom she considered as a kind of guard. Thus circumstanced, she tried to banish reflection, but her busy fancy would still hover over the subjects of her interest, and she heard the clock of the castle strike two, before she closed her eyes. From the disturbed slumber into which she then sunk, she was soon awakened by a noise, which seemed to arise within her chamber; but the silence that prevailed, as she fearfully listened, inclined her to believe that she had been alarmed by such sounds as sometimes occur in dreams, and she laid her head again upon the pillow. A return of the noise again disturbed her; it seemed to come from that part of the room which communicated with the private stair-case, and she instantly remembered the odd circumstance of the door having been fastened, during the preceding night, by some unknown hand. Her late alarming suspicion, concerning its communication, also occurred to her. Her heart became faint with terror. Half raising herself from the bed, and gently drawing aside the curtain, she looked towards the door of the stair-case, but the lamp that burnt on the hearth spread so feeble a light through the apartment that the remote parts of it were lost in shadow. The noise, however, which, she was convinced, came from the door, continued. It seemed like that made by the undrawing of rusty bolts, and often ceased, and was then renewed more gently, as if the hand that occasioned it was restrained by a fear of discovery. While Emily kept her eyes fixed on the spot, she saw the door move, and then slowly open, and perceived something enter the room, but the extreme duskiness prevented her distinguishing what it was. Almost fainting with terror, she had yet sufficient command over herself to check the shriek that was escaping from her lips, and, letting the curtain drop from her hand, continued to observe in silence the motions of the mysterious form she saw. It seemed to glide along the remote obscurity of the apartment, then paused, and, as it approached the hearth, she perceived, in the stronger light, what appeared to be a human figure. Certain remembrances now struck upon her heart, and almost subdued the feeble remains of her spirits; she continued, however, to watch the figure, which remained for some time motionless, but then, advancing slowly towards the bed, stood silently at the feet, where

"Who is there?" said Ambrosio at length. "It is only Rosario," replied a gentle voice. The Monk -1796 - Matthew Gregory Lewis Chapter 8 Extract It was almost two o'clock before the lustful monk ventured to bend his steps towards Antonia's dwelling. It has been already mentioned that the abbey was at no great distance from the strada di San Iago. He reached the house unobserved. Here he stopped, and hesitated for a moment. He reflected on the enormity of the crime, the consequences of a discovery, and the probability, after what had passed, of Elvira's suspecting him to be her daughter's ravisher. On the other hand it was suggested that she could do no more than suspect; that no proofs of his guilt could be produced; that it would seem impossible for the rape to have been committed without Antonia's knowing when, where, or by whom; and finally, he believed that his fame was too firmly established to be shaken by the unsupported accusations of two unknown women. This latter argument was perfectly false. He knew not how uncertain is the air of popular applause, and that a moment suffices to make him to-day the detestation of the world, who yesterday was its idol. The result of the monk's deliberations was that he should proceed in his enterprise. He ascended the steps leading to the house. No sooner did he touch the door with the silver myrtle than it flew open, and presented him with a free passage. He entered, and the door closed after him of its own accord. Guided by the moon-beams, he proceeded up the stair-case with slow and cautious steps. He looked round him every moment with apprehension and anxiety. He saw a spy in every shadow, and heard a voice in every murmur of the night-breeze. Consciousness of the guilty business on which he was employed appalled his heart, and rendered it more timid than a woman's. Yet still he proceeded. He reached the door of Antonia's chamber. He stopped, and listened. All was hushed within. The total silence persuaded him that his intended victim was retired to rest, and he ventured to lift up the latch. The door was fastened, and resisted his efforts. But no sooner was it touched by the talisman than the bolt flew back. The ravisher stepped on, and found himself in the chamber where slept the innocent girl, unconscious how dangerous a visitor was drawing near her couch. The door closed after him, and the bolt shot again into its fastening. Ambrosio advanced with precaution. He took care that not a board should creak under his foot, and held in his breath as he approached the bed. His first attention was to perform the magic ceremony, as Matilda had charged him: he breathed thrice upon the silver myrtle, pronounced over it Antonia's name, and laid it upon her pillow. The effects which it had already produced permitted not his doubting its success in prolonging the slumbers of his devoted mistress. No sooner was the enchantment performed than he considered her to be absolutely in his power, and his eyes flashed with lust and impatience. He now ventured to cast a glance upon the sleeping beauty. A single lamp, burning before the statue of St. Rosolia, shed a faint light through the room, and permitted him to examine all the charms of the lovely object before him. The heat of the weather had obliged her to throw off part of the bed-clothes. Those which still covered her Ambrosio's insolent hand hastened to remove. She lay with her cheek reclining upon one ivory arm: the other rested on the side of the bed with graceful indolence. A few tresses of her hair had escaped from beneath the muslin which confined the rest, and fell carelessly over her bosom, as it heaved with slow and regular suspiration. The warm air had spread her cheek with a higher colour than usual. A smile inexpressibly sweet played round her ripe and coral lips, from which every now and then escaped a gentle sigh, or an half-pronounced sentence. An air of enchanting innocence and candour pervaded her whole form; and there was a sort of modesty in her very nakedness, which added fresh stings to the desires of the lustful monk. He remained for some moments devouring those charms with his eyes which soon were to be subjected to his ill-regulated passions. Her mouth half-opened seem to solicit a kiss: he bent over her: he joined his lips to hers, and drew in the fragrance of her breath with rapture. This momentary pleasure increased his longing for still greater. His desires were raised to that frantic height by which brutes are agitated. He resolved not to delay for one instant longer the accomplishment of his wishes, and hastily proceeded to tear off those garments which impeded the gratification of his lust. "Gracious God!" exclaimed a voice behind him: "Am I not deceived? Is not this an illusion?" Terror, confusion, and disappointment accompanied these words, as they struck Ambrosio's hearing. He started, and turned towards it. Elvira stood at the door of the chamber, and regarded the monk with looks of surprise and detestation.

A frightful dream had represented to her Antonia on the verge of a precipice. She saw her trembling on the brink: every moment seemed to threaten her fall, and she heard her exclaim with shrieks, "Save me, mother! save me! — Yet a moment, and it will be too late." Elvira woke in terror. The vision had made too strong an impression upon her mind to permit her resting till assured of her daughter's safety. She hastily started from her bed, threw on a loose night-gown, and, passing through the closet in which slept the waiting-woman, reached Antonia's chamber just in time to rescue her from the grasp of the ravisher. His shame and her amazement seemed to have petrified into statues both Elvira and the monk. They remained gazing upon each other in silence. The lady was the first to recover herself. "It is no dream," she cried: "it is really Ambrosio who stands before me. It is the man whom Madrid esteems a saint that I find at this late hour near the couch of my unhappy child. Monster of hypocrisy! I already suspected your designs, but forbore your accusation in pity to human frailty. Silence would now be criminal. The whole city shall be informed of your incontinence. I will unmask you, villain, and convince the church what a viper she cherishes in her bosom." Pale and confused, the baffled culprit stood trembling before her. He would fain have extenuated his offence, but could find no apology for his conduct. He could produce nothing but broken sentences, and excuses which contradicted each other. Elvira was too justly incensed to grant the pardon which he requested. She protested that she would raise the neighbourhood, and make him an example to all future hypocrites. Then hastening to the bed, she called to Antonia to wake; and finding that her voice had no effect, she took her arm, and raised her forcibly from the pillow. The charm operated too powerfully. Antonia remained insensible; and, on being released by her mother, sank back upon the pillow. "This slumber cannot be natural," cried the amazed Elvira, whose indignation increased with every moment: "some mystery is concealed in it. But tremble, hypocrite! All your villainy shall soon be unravelled. Help! help!" she exclaimed aloud: "Within there! Flora! Flora!" "Hear me for one moment, lady!" cried the monk, restored to himself by the urgency of the danger: "by all that is sacred and holy, I swear that your daughter's honour is still unviolated. Forgive my transgression! Spare me the shame of a discovery, and permit me to regain the abbey undisturbed. Grant me this request in mercy! I promise not only that Antonia shall be secure from me in future, but that the rest of my life shall prove — " Elvira interrupted him abruptly. "Antonia secure from you? I will secure her. You shall betray no longer the confidence of parents. Your iniquity shall be unveiled to the public eye. All Madrid shall shudder at your perfidy, your hypocrisy, and incontinence. What ho! there! Flora! Flora! I say." While she spoke thus, the remembrance of Agnes struck upon his mind. Thus had she sued to him for mercy, and thus had he refused her prayer! It was now his turn to suffer, and he could not but acknowledge that his punishment was just. In the mean while Elvira continued to call Flora to her assistance; but her voice was so choaked with passion, that the servant, who was buried in profound slumber, was insensible to all her cries: Elvira dared not go towards the closet in which Flora slept, lest the monk should take that opportunity to escape. Such indeed was his intention: he trusted that, could he reach the abbey unobserved by any other than Elvira, her single testimony would not suffice to ruin a reputation so well established as his was in Madrid. With this idea he gathered up such garments as he had already thrown off, and hastened towards the door. Elvira was aware of his design: she followed him, and, ere he could draw back the bolt, seized him by the arm, and detained him. "Attempt not to fly!" said she: "you quit not this room without witnesses of your guilt." Ambrosio struggled in vain to disengage himself. Elvira quitted not her hold, but redoubled her cries for succour. The friar's danger grew more urgent. He expected every moment to hear people assembling at her voice; and, worked up to madness by the approach of ruin, he adopted a resolution equally desperate and savage. Turning round suddenly, with one hand he grasped Elvira's throat so as to prevent her continuing her clamour, and with the other, dashing her violently upon the ground, he dragged her towards the bed. Confused by this unexpected attack, she scarcely had power to strive at forcing herself from his grasp: while the monk, snatching the pillow from beneath her daughter's head, covering with it Elvira's face, and pressing his knee upon her stomach with all his strength, endeavoured to put an end to her existence. He succeeded but too well. Her natural strength increased by the excess of anguish, long did the sufferer struggle to disengage herself, but in vain. The monk continued to kneel upon her breast, witnessed without mercy the convulsive trembling of her limbs beneath him, and sustained with inhuman firmness the spectacle of her agonies, when soul and body were on the point of separating. Those agonies at length were over. She ceased to struggle for life. The monk took off the pillow, and gazed upon her. Her face was covered with a frightful blackness: her limbs moved no more: the blood was chilled in her veins: her heart had forgotten to beat; and her hands were stiff and frozen. Ambrosio beheld before him that once noble and majestic form, now become a corse, cold, senseless, and disgusting. This horrible act was no sooner perpetrated, than the friar beheld the enormity of his crime. A cold dew flowed over his limbs: his eyes closed: he staggered to a chair, and sank into it almost as lifeless as the unfortunate who lay extended at his feet. From this state he was roused by the necessity of flight, and the danger of being found in Antonia's apartment. He had no desire to profit by the execution of his crime. Antonia now appeared to him an object of disgust. A deadly cold had usurped the place of

away. Vivaldi followed him with his eyes, till a door at the extremity of the passage opened, and he saw the Inquisitor enter an apartment, whence a great light proceeded, and where several other figures, habited like himself, appeared waiting to receive him. The door immediately closed; and, whether the imagination of Vivaldi was affected, or that the founds were real, he thought, as it closed, he distinguished half-stifled groans, as of a person in agony. Northanger Abbey - 1817 - Jane Austen – Volume 2, Chapter 5 Extract "You must be so fond of the abbey! — After being used to such a home as the abbey, an ordinary parsonage-house must be very disagreeable." He smiled, and said, "You have formed a very favourable idea of the abbey." "To be sure I have. Is not it a fine old place, just like what one reads about?" "And are you prepared to encounter all the horrors that a building such as 'what one reads about' may produce? — Have you a stout heart? — Nerves fit for sliding panels and tapestry?" "Oh! yes — I do not think I should be easily frightened, because there would be so many people in the house — and besides, it has never been uninhabited and left deserted for years, and then the family come back to it unawares, without giving any notice, as generally happens." "No, certainly. — We shall not have to explore our way into a hall dimly lighted by the expiring embers of a wood fire — nor be obliged to spread our beds on the floor of a room without windows, doors, or furniture. But you must be aware that when a young lady is (by whatever means) introduced into a dwelling of this kind, she is always lodged apart from the rest of the family. While they snugly repair to their own end of the house, she is formally conducted by Dorothy the ancient housekeeper up a different staircase, and along many gloomy passages, into an apartment never used since some cousin or kin died in it about twenty years before. Can you stand such a ceremony as this? Will not your mind misgive you, when you find yourself in this gloomy chamber — too lofty and extensive for you, with only the feeble rays of a single lamp to take in its size — its walls hung with tapestry exhibiting figures as large as life, and the bed, of dark green stuff or purple velvet, presenting even a funereal appearance. Will not your heart sink within you?" "Oh! but this will not happen to me, I am sure." "How fearfully will you examine the furniture of your apartment! — And what will you discern? — Not tables, toilettes, wardrobes, or drawers, but on one side perhaps the remains of a broken lute, on the other a ponderous chest which no efforts can open, and over the fire-place the portrait of some handsome warrior, whose features will so incomprehensibly strike you, that you will not be able to withdraw your eyes from it. Dorothy meanwhile, no less struck by your appearance, gazes on you in

great agitation, and drops a few unintelligible hints. To raise your spirits, moreover, she gives you reason to suppose that the part of the abbey you inhabit is undoubtedly haunted, and informs you that you will not have a single domestic within call. With this parting cordial she curtseys off — you listen to the sound of her receding footsteps as long as the last echo can reach you — and when, with fainting spirits, you attempt to fasten your door, you discover, with increased alarm, that it has no lock." "Oh! Mr. Tilney, how frightful! — This is just like a book! — But it cannot really happen to me. I am sure your housekeeper is not really Dorothy. — Well, what then?" "Nothing further to alarm perhaps may occur the first night. After surmounting your unconquerable horror of the bed, you will retire to rest, and get a few hours' unquiet slumber. But on the second, or at farthest the third night after your arrival, you will probably have a violent storm. Peals of thunder so loud as to seem to shake the edifice to its foundation will roll round the neighbouring mountains — and during the frightful gusts of wind which accompany it, you will probably think you discern (for your lamp is not extinguished) one part of the hanging more violently agitated than the rest. Unable of course to repress your curiosity in so favourable a moment for indulging it, you will instantly arise, and throwing your dressing-gown around you, proceed to examine this mystery. After a very short search, you will discover a division in the tapestry so artfully constructed as to defy the minutest inspection, and on opening it, a door will immediately appear — which door being only secured by massy bars and a padlock, you will, after a few efforts, succeed in opening, — and, with your lamp in your hand, will pass through it into a small vaulted room." "No, indeed; I should be too much frightened to do any such thing." "What! not when Dorothy has given you to understand that there is a secret subterraneous communication between your apartment and the chapel of St. Anthony, scarcely two miles off — Could you shrink from so simple an adventure? No, no, you will proceed into this small vaulted room, and through this into several others, without perceiving anything very remarkable in either. In one perhaps there may be a dagger, in another a few drops of blood, and in a third the remains of some instrument of torture; but there being nothing in all this out of the common way, and your lamp being nearly exhausted, you will return towards your own apartment. In repassing through the small vaulted room, however, your eyes will be attracted towards a large, old-fashioned cabinet of ebony and gold, which, though narrowly examining the furniture before, you had passed unnoticed. Impelled by an irresistible presentiment, you will eagerly advance to it, unlock its folding doors, and search into every drawer; — but for some time without discovering anything of importance — perhaps nothing but a considerable hoard of diamonds. At last, however, by touching a secret spring, an inner compartment will open — a roll of paper appears: — you seize it — it contains many sheets of manuscript — you hasten with the precious treasure into your own chamber, but scarcely have you been able to decipher 'Oh! thou — whomsoever thou mayst be, into whose hands these memoirs of the wretched Matilda may fall' — when your lamp suddenly expires in the socket, and leaves you in total darkness." "Oh! no, no — do not say so. Well, go on." But Henry was too amused by the interest he had raised, to be able to carry it farther; he could no longer command solemnity either of subject or voice, and was obliged to entreat her to use her own fancy in the perusal of Matilda's woes. Catherine, recollecting herself, grew ashamed of her eagerness, and began earnestly to assure him that her attention had been fixed without the smallest apprehension of really meeting with what he related. "Miss Tilney, she was sure, would never put her into such a chamber as he had described! — She was not at all afraid."

and every limb became convulsed: when, by the dim and yellow light of the moon, as it forced its way through the window shutters, I beheld the wretch -- the miserable monster whom I had created. He held up the curtain of the bed; and his eyes, if eyes they may be called, were fixed on me. His jaws opened, and he muttered some inarticulate sounds, while a grin wrinkled his cheeks. He might have spoken, but I did not hear; one hand was stretched out, seemingly to detain me, but I escaped, and rushed down stairs. I took refuge in the courtyard belonging to the house which I inhabited; where I remained during the rest of the night, walking up and down in the greatest agitation, listening attentively, catching and fearing each sound as if it were to announce the approach of the demoniacal corpse to which I had so miserably given life. Oh! no mortal could support the horror of that countenance. A mummy again endued with animation could not be so hideous as that wretch. I had gazed on him while unfinished; he was ugly then; but when those muscles and joints were rendered capable of motion, it became a thing such as even Dante could not have conceived. I passed the night wretchedly. Sometimes my pulse beat so quickly and hardly that I felt the palpitation of every artery; at others, I nearly sank to the ground through languor and extreme weakness. Mingled with this horror, I felt the bitterness of disappointment; dreams that had been my food and pleasant rest for so long a space were now become a hell to me; and the change was so rapid, the overthrow so complete! Morning, dismal and wet, at length dawned, and discovered to my sleepless and aching eyes the church of Ingolstadt, its white steeple and clock, which indicated the sixth hour. The porter opened the gates of the court, which had that night been my asylum, and I issued into the streets, pacing them with quick steps, as if I sought to avoid the wretch whom I feared every turning of the street would present to my view. I did not dare return to the apartment which I inhabited, but felt impelled to hurry on, although drenched by the rain which poured from a black and comfortless sky. I continued walking in this manner for some time, endeavouring, by bodily exercise, to ease the load that weighed upon my mind. I traversed the streets, without any clear conception of where I was, or what I was doing. My heart palpitated in the sickness of fear; and I hurried on with irregular steps, not daring to look about me:-- "Like one who, on a lonely road, Doth walk in fear and dread, And, having once turned round, walks on, And turns no more his head; Because he knows a frightful fiend Doth close behind him tread." The Rime of the Ancient Mariner (1798), Samuel Taylor Coleridge

Nightmare Abbey – 1818 - Thomas Love Peacock – Chapter 3 Extract Miss Marionetta Celestina O'Carroll was a very blooming and accomplished young lady. Being a compound of the Allegro Vivace of the O'Carrolls, and of the Andante Doloroso of the Glowrys, she exhibited in her own character all the diversities of an April sky. Her hair was light-brown: her eyes hazel, and sparkling with a mild but fluctuating light: her features regular: her lips full, and of equal size: and her person surpassingly graceful. She was a proficient in music. Her conversation was sprightly, but always on subjects light in their nature and limited in their interest: for moral sympathies, in any general sense, had no place in her mind. She had some coquetry, and more caprice, liking and disliking almost in the same moment; pursuing an object with earnestness while it seemed unattainable, and rejecting it when in her power as not worth the trouble of possession. Whether she was touched with a penchant for her cousin Scythrop, or was merely curious to see what effect the tender passion would have on so outré >> note 1 a person, she had not been three days in the Abbey before she threw out all the lures of her beauty and accomplishments to make a prize of his heart. Scythrop proved an easy conquest. The image of Miss Emily Girouette was already sufficiently dimmed by the power of philosophy and the exercise of reason: for to these influences, or to any influence but the true one, are usually ascribed the mental cures performed by the great physician Time. Scythrop's romantic dreams had indeed given him many pure anticipated cognitions of combinations of beauty and intelligence, which, he had some misgivings, were not exactly realised in his cousin Marionetta; but, in spite of these misgivings, he soon became distractedly in love; which when the young lady clearly perceived, she altered her tactics, and assumed as much coldness and reserve as she had before shewn ardent and ingenuous attachment. Scythrop was confounded at the sudden change; but, instead of falling at her feet and requesting an explanation, he retreated to his tower, muffled himself in his night-cap, seated himself in the president's chair of his imaginary secret tribunal, summoned Marionetta with all terrible formalities, frightened her out of her wits, disclosed himself, and clasped the beautiful penitent to his bosom. While he was acting this reverie — in the moment in which the awful president of the secret tribunal was throwing back his cowl and his mantle, and discovering himself to the lovely culprit

could have made the angles of time and place coincide in our unfortunate persons at the head of this accursed staircase?" "Nothing else, certainly," said Scythrop: "you are perfectly in the right, Mr. Toobad. Evil, and mischief, and misery, and confusion, and vanity, and vexation of spirit, and death, and disease, and assassination, and war, and poverty, and pestilence, and famine, and avarice, and selfishness, and rancour, and jealousy, and spleen, and malevolence, and the disappointments of philanthropy, and the faithlessness of friendship, and the crosses of love, — all prove the accuracy of your views, and the truth of your system; and it is not impossible that the infernal interruption of this fall down stairs may throw a colour of evil on the whole of my future existence." "My dear boy," said Mr. Toobad, "you have a fine eye for consequences." So saying, he embraced Scythrop, who retired, with a disconsolate step, to dress for dinner; while Mr. Toobad stalked across the hall, repeating, "Woe to the inhabiters of the earth, and of the sea, for the devil is come among you, having great wrath." A Night in the Catacombs – 1818 - Daniel Keyte Sandford The interminable rows of bare and blackening skulls—the masses interposed of gaunt and rotting bones, that once gave strength and symmetry to the young, the beautiful, the brave, now mildewed by the damp of the cavern, and heaped together in indiscriminate arrangement—the faint mouldering and deathlike smell that pervaded these gloomy labyrinths, and the long recesses in the low-roofed rock, to which I dared not turn my eyes except by short and fitful glances, as if expecting something terrible and ghastly to start from the indistinctness of their distance, —all had associations for my thoughts very different from the solemn and edifying sentiments they must rouse in a well regulated breast, and, by degrees, I yielded up every faculty to the influence of an ill-defined and mysterious alarm. My eyesight waxed gradually dull to all but the fleshless skulls that were glaring in the yellow light of the tapers— the hum of human voices was stifled in my ears, and I thought myself alone, already with the dead. The guide thrust the light he carried into a huge skull that was lying separate in a niche ; but I marked not the action or the man, but only the fearful glimmering of the transparent bone, which I

thought a smile of triumphant malice from the presiding spectre of the place, while imagined accents whispered, in my hearing, “ Welcome to our charnel- house 1 , for THIS shall be your chamber !” Dizzy with indescribable emotions, I felt nothing but a painful sense of oppression from the presence of others, as if I could not breathe for the black shapes that were crowding near me ; and turning unperceived, down a long and gloomy passage of the catacombs, I rushed as far as I could penetrate, to feed in solitude the growing appetite for horror, that had quelled for the moment, in my bosom, the sense of fear, and even the feeling of identity. To the rapid whirl of various sensations that had bewildered me ever since I left the light of day, a season of intense abstraction now succeeded. I held my burning eyeballs full upon the skulls in front, till they almost seemed to answer my fixed regard, and claim a dreadful fellowship with the being that beheld them. The Tell-Tale Heart – 1843 – Edgar Allan Poe True! --nervous --very, very dreadfully nervous I had been and am; but why will you say that I am mad? The disease had sharpened my senses --not destroyed --not dulled them. Above all was the sense of hearing acute. I heard all things in the heaven and in the earth. I heard many things in hell. How, then, am I mad? Hearken! and observe how healthily --how calmly I can tell you the whole story. It is impossible to say how first the idea entered my brain; but once conceived, it haunted me day and night. Object there was none. Passion there was none. I loved the old man. He had never wronged me. He had never given me insult. For his gold I had no desire. I think it was his eye! yes, it was this! He had the eye of a vulture --a pale blue eye, with a film over it. Whenever it fell upon me, my blood ran cold; and so by degrees --very gradually --I made up my mind to take the life of the old man, and thus rid myself of the eye forever. Now this is the point. You fancy me mad. Madmen know nothing. But you should have seen me. You should have seen how wisely I proceeded --with what caution --with what foresight --with what dissimulation I went to work! I was never kinder to the old man than during the whole week before I killed him. And every night, about midnight, I turned the latch of his door and opened it --oh so gently! And then, when I had made an opening sufficient for my head, I put in a dark lantern, all closed, closed, that no light shone out, and then I thrust in my head. Oh, you would have laughed to see how cunningly I thrust it in! I moved it slowly --very, very slowly, so that I might not disturb the old man's sleep. It took me an hour to place my whole head within the opening so far that I could see him as he lay upon his bed. Ha! would a madman have been so wise as this, And then, when my head was well in the room, I undid the lantern cautiously-oh, so cautiously --cautiously (for the hinges creaked) --I undid it just so much that a single thin ray fell upon the vulture eye. And this I did for seven long nights --every night just at midnight --but I found the eye always closed; and so it was impossible to do the work; for it was not the old man who vexed me, but his Evil Eye. And every morning, when the day broke, I went boldly into the

Gothic Extracts Booklet

Subject: English Literature

Sixth Form (A Levels)

• A2 - A LevelThis is a preview

Access to all documents

Get Unlimited Downloads

Improve your grades

This is a preview

Access to all documents

Get Unlimited Downloads

Improve your grades

Why is this page out of focus?

This is a preview

Access to all documents

Get Unlimited Downloads

Improve your grades

Why is this page out of focus?

This is a preview

Access to all documents

Get Unlimited Downloads

Improve your grades

Why is this page out of focus?

This is a preview

Access to all documents

Get Unlimited Downloads

Improve your grades

Why is this page out of focus?

This is a preview

Access to all documents

Get Unlimited Downloads

Improve your grades

Why is this page out of focus?

This is a preview

Access to all documents

Get Unlimited Downloads

Improve your grades

Why is this page out of focus?

This is a preview

Access to all documents

Get Unlimited Downloads

Improve your grades

Why is this page out of focus?

This is a preview

Access to all documents

Get Unlimited Downloads

Improve your grades

Why is this page out of focus?

This is a preview

Access to all documents

Get Unlimited Downloads

Improve your grades

Why is this page out of focus?

This is a preview

Access to all documents

Get Unlimited Downloads

Improve your grades

Why is this page out of focus?

This is a preview

Access to all documents

Get Unlimited Downloads

Improve your grades

Why is this page out of focus?

This is a preview

Access to all documents

Get Unlimited Downloads

Improve your grades

Why is this page out of focus?

This is a preview

Access to all documents

Get Unlimited Downloads

Improve your grades

Why is this page out of focus?

This is a preview

Access to all documents

Get Unlimited Downloads

Improve your grades

Why is this page out of focus?

This is a preview

Access to all documents

Get Unlimited Downloads

Improve your grades

Why is this page out of focus?

This is a preview

Access to all documents

Get Unlimited Downloads

Improve your grades

Why is this page out of focus?

This is a preview

Access to all documents

Get Unlimited Downloads

Improve your grades

Why is this page out of focus?

This is a preview

Access to all documents

Get Unlimited Downloads

Improve your grades

Why is this page out of focus?

This is a preview

Access to all documents

Get Unlimited Downloads

Improve your grades

Why is this page out of focus?

This is a preview

Access to all documents

Get Unlimited Downloads

Improve your grades

Why is this page out of focus?

This is a preview

Access to all documents

Get Unlimited Downloads

Improve your grades

Why is this page out of focus?

This is a preview

Access to all documents

Get Unlimited Downloads

Improve your grades

Why is this page out of focus?

This is a preview

Access to all documents

Get Unlimited Downloads

Improve your grades

Why is this page out of focus?

This is a preview

Access to all documents

Get Unlimited Downloads

Improve your grades

Why is this page out of focus?

This is a preview

Access to all documents

Get Unlimited Downloads

Improve your grades

Why is this page out of focus?

This is a preview

Access to all documents

Get Unlimited Downloads

Improve your grades

Why is this page out of focus?

This is a preview

Access to all documents

Get Unlimited Downloads

Improve your grades

Why is this page out of focus?

This is a preview

Access to all documents

Get Unlimited Downloads

Improve your grades

Why is this page out of focus?

This is a preview

Access to all documents

Get Unlimited Downloads

Improve your grades

Why is this page out of focus?

This is a preview

Access to all documents

Get Unlimited Downloads

Improve your grades

Why is this page out of focus?

This is a preview

Access to all documents

Get Unlimited Downloads

Improve your grades

Why is this page out of focus?

This is a preview

Access to all documents

Get Unlimited Downloads

Improve your grades

Why is this page out of focus?

This is a preview

Access to all documents

Get Unlimited Downloads

Improve your grades

Why is this page out of focus?

This is a preview

Access to all documents

Get Unlimited Downloads

Improve your grades

Why is this page out of focus?

This is a preview

Access to all documents

Get Unlimited Downloads

Improve your grades

Why is this page out of focus?

This is a preview

Access to all documents

Get Unlimited Downloads

Improve your grades

Why is this page out of focus?

This is a preview

Access to all documents

Get Unlimited Downloads

Improve your grades

Why is this page out of focus?

This is a preview

Access to all documents

Get Unlimited Downloads

Improve your grades

Why is this page out of focus?

This is a preview

Access to all documents

Get Unlimited Downloads

Improve your grades

Why is this page out of focus?

This is a preview

Access to all documents

Get Unlimited Downloads

Improve your grades

Why is this page out of focus?

This is a preview

Access to all documents

Get Unlimited Downloads

Improve your grades

Why is this page out of focus?

This is a preview

Access to all documents

Get Unlimited Downloads

Improve your grades

Why is this page out of focus?

This is a preview

Access to all documents

Get Unlimited Downloads

Improve your grades