The Iron Curtain (film)

| The Iron Curtain | |

|---|---|

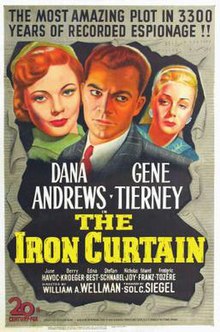

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | William A. Wellman |

| Screenplay by | Milton Krims |

| Based on | I Was Inside Stalin's Spy Ring 1947 articles in Hearst's International-Cosmopolitan by Igor Gouzenko |

| Produced by | Sol C. Siegel |

| Starring | Dana Andrews Gene Tierney |

| Narrated by | Reed Hadley |

| Cinematography | Charles G. Clarke |

| Edited by | Louis R. Loeffler |

| Music by | Alfred Newman |

| Color process | Black and white |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | 20th Century-Fox |

Release date |

|

Running time | 87 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Box office | $2 million (US rentals)[1] |

The Iron Curtain is a 1948 American thriller film starring Dana Andrews and Gene Tierney, directed by William A. Wellman. It was the first film on the Cold War.[2] The film was based on the memoirs of Igor Gouzenko.[3] Principal photography was done on location in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada by Charles G. Clarke.[4] The film was later re-released as Behind the Iron Curtain.

In Shostakovich v. Twentieth Century-Fox, Russian composer Dmitry Shostakovich unsuccessfully sued 20th Century-Fox, the film's distributor, in New York court, for using musical works of his that could not be excluded from the public domain. However, the plaintiffs were victorious in the French analog Société Le Chant du Monde v. Société Fox Europe and Société Fox Americaine Twentieth Century.

Plot[edit]

Igor Gouzenko (Dana Andrews), an expert at deciphering codes, comes to the Soviet embassy in Ottawa in 1943, along with a Soviet military colonel, Trigorin (Frederic Tozere), and a major, Kulin (Eduard Franz), to set up a base of operations.

Warned of the sensitive and top-secret nature of his work, Igor is put to a test by his superiors, who have the seductive Nina Karanova (June Havoc) try her wiles on him. Igor proves loyal to not only the cause but to his wife, Anna (Gene Tierney), who arrives in Ottawa shortly thereafter with the news that she is pregnant.

Trigorin and his security chief, Ranov (Stefan Schnabel), meet with John Grubb (Berry Kroeger), the founder of Canada's branch of the Communist Party. One of their primary targets is uranium being used for atomic energy by Dr. Harold Norman (Nicholas Joy), whom they try to recruit.

In the years that pass, the atomic bomb ends the war. Anna, who has borne a son, now has serious doubts about the family's future. Igor begins to share these doubts, particularly after one of his colleagues, Kulin, has a breakdown and is placed under arrest. Once Igor is told that he is going to be reassigned back to Moscow, he decides to take action. He takes secret documents from the Embassy and tells Anna to hide them, in case anything happens to him. Trigorin and Ranov threaten his life, and the lives of his and Anna's families in the Soviet Union, but Igor refuses to return the papers.

Grubb and several others are called back to the Soviet Union to answer for their failures. Because of the documents Igor took, Canada's government succeeds in dismantling the communist cabal in the country and places the Gouzenkos in protective custody and grants them residence. The film ends with the proviso that the family lives in hiding protected by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. "Yet they have not lost faith in the future. They know that ultimate security for themselves and their children lies in the survival of the democratic way of life".

Cast[edit]

- Dana Andrews as Igor Gouzenko

- Gene Tierney as Anna Gouzenko

- June Havoc as Nina Karanova

- Berry Kroeger as John Grubb, aka 'Paul'

- Edna Best as Mrs. Albert Foster, neighbor

- Stefan Schnabel as Col. Ilya Ranov, embassy attache

- Eduard Franz as Maj. Semyon Kulin

- Nicholas Joy as Dr. Harold Preston Norman, aka 'Alec'

- Frederic Tozere as Col. Aleksandr Trigorin

Production[edit]

Twentieth Century-Fox bought the rights to Gouzenko's articles about his experiences, as Hollywood began producing films regarding Communist infiltration in the late 1940s. The studio also purchased the rights to two historical books on Soviet espionage, George Moorad's Behind the Iron Curtain and Richard Hirsch's The Soviet Spies: The Story of Russian Espionage in North America, but no material from the two books was used in the film.[3] The film was produced by Daryl F. Zanuck in response to claims by Rep. J. Parnell Thomas, chairman of the House Un-American Activities Committee, that Hollywood did not make anti-communist films.[5]

Soviet sympathizers attempted unsuccessfully to disrupt location shooting in Ottawa, where Fox captured exteriors during a cold Canadian winter.[3]

Reception[edit]

In a blurb noting the movie's release, The New York Times observed: "The Iron Curtain...has been under attack since January by various groups including the National Council of American-Soviet Friendship."[6]

The New York Times' Bosley Crowther opens his May 13, 1948, review with “Hollywood fired its first Shot in the "cold war" against Russia yesterday, just when a faint hope was glimmering that maybe moderation in fact might be achieved. It came in the shape of The Iron Curtain,” Crowther praises Gene Tierney's “glowing” performance, but has little good to say—and a great deal to criticize—when it comes to the rest of the film. Comparing it to 1939's Confessions of a Nazi Spy (the pictures share a screenwriter), he observes: “It…seems excessively sensational and dangerous to the dis-ease of our times to dramatize the myrmidons of Russia as so many sinister fiends.” Although it is supposed to be based on a true account, “This story and film have a patent detachment from authenticity…This would pass for a mild spy melodrama if it weren't for the violence of its blast…There is no question about it. It is an highly inflammatory film.”[7]

On May 16, 1948, in “The Iron Curtain: New Roxy Film Poses a Question: Is It Being Raised or Lowered?” Crowther explores the powerful influence of film on audiences and the dangers of demonizing Russians, or any people.[8]

Darryl F. Zanuck wrote in response to the May 16 piece. His letter was published on May 30, 1948.[9]

The film opened in 20 key cities in the United States and grossed over $500,000 in its first week to be the number one film in the United States where it remained for a second week.[10][11]

References[edit]

- ^ "Top Grossers of 1948", Variety 5 January 1949 p 46

- ^ Christopher Newfield (2020). "Cold War and Culture War". In Paul Lauter (ed.). Blackwell Companions to Literature and Culture A Companion to American Literature and Culture Genealogies of American Literary Study. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 76. doi:10.1002/9781444320626.ch5. ISBN 9781444320626.

- ^ a b c "The Iron Curtain". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved April 28, 2014.

- ^ Higham, Charles; Greenberg, Joel (1968). Hollywood in the Forties. London: A. Zwemmer Limited. p. 75. ISBN 0-302-00477-7.

- ^ Doherty, Thomas. (2018) Show Trial, Columbia University Press, p. 62.

- ^ "Of Local Origin". New York Times. May 12, 1948. p. 33 (Amusements). Retrieved April 27, 2020.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (May 13, 1948). "THE SCREEN; ' The Iron Curtain,' Anti-Communist Film, Has Premiere Here at the Roxy Theatre". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 5, 2023.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (May 16, 1948). "'THE IRON CURTAIN'; New Roxy Film Poses a Question: Is It Being Raised or Lowered?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 5, 2023.

- ^ Zanuck, Darryl F. (May 30, 1948). "ZANUCK DEFENDS 'THE IRON CURTAIN'". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 5, 2023.

- ^ "National Boxoffice Survey". Variety. May 19, 1948. p. 3. Retrieved December 29, 2023 – via Archive.org.

- ^ "National Boxoffice Survey". Variety. May 26, 1948. p. 3. Retrieved December 29, 2023 – via Archive.org.

External links[edit]

- 1948 films

- 1940s spy thriller films

- American spy thriller films

- American anti-communist propaganda films

- American black-and-white films

- Cold War spy films

- 1940s English-language films

- Films directed by William A. Wellman

- Spy films based on actual events

- 20th Century Fox films

- Films scored by Alfred Newman

- Films set in the 1940s

- 1940s crime films

- Films shot in Ontario

- American biographical films

- Works about Canada and the Cold War

- 1940s American films