By the time he was 15, Tejano music pioneer Joe “Little Joe” DeLeón Hernández had taken a stance to pick the guitar instead of cotton.

He was amazed to make $5 on his first paying gig — he would have had to pick 500 pounds of cotton to earn that — and he never looked back.

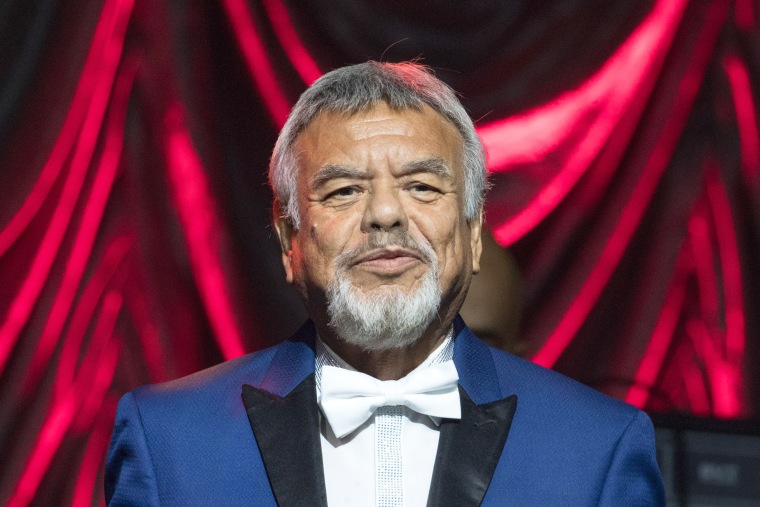

More than 62 years later, "King of the Brown Sound" on Friday received the National Heritage Fellowship Award from the National Endowment of the Arts, the highest national award that honors the artistic genius of traditional artists “at the intersection of past, present and future and at the intersection of preservation and innovation,” according to NEA Chair Maria Rosario Jackson.

It's a fitting tribute to the Mexican American music legend, who has recorded more than 70 albums and won four Grammys and a Latin Grammy (from a combined 11 nominations) and who was named the Texas State Artist of the Year in 2019.

Little Joe is credited with putting Tejano, or Tex-Mex, music on the map. It’s a pioneering Chicano sound that's an up-tempo hybrid of the many genres he grew up hearing in both Spanish and English: Mexican conjunto norteño, country, blues, rock, big band, cumbia, merengue and more.

He has also opened doors and influenced other artists — including the late singing legend Selena — and he has been a symbol of activism and civil rights. Little Joe's iconic song "Las Nubes" is considered an anthem for the farmworker movement, which he has supported among other causes, including Farm Aid, where he performed with Willie Nelson.

Among his other well-known songs are "Por Un Amor," "Margarita," "Prieta Linda" and "Redneck Meskin Boy."

The King of the Brown Sound was born José María DeLeón Hernández on a thunderous stormy night in a three-walled dirt floor garage where his family lived in Temple, Texas, on Oct. 17, 1940.

He was the seventh of 13 children born to Salvador and Amelia De Leon Hernández, and his first piercing cry is fondly remembered by his older brother Jim Hernández as a little “grito,” or yell, “naturally going along with the storm,” as detailed in Little Joe's 2020 authorized biography, “¡No Llore Chingón! An American Story, The Life of Little Joe.”

A "grito," a powerful, emotive cry or yell that's popular in Mexican music, is one of the hallmarks of Little Joe’s live shows and many of his songs.

Music was a family affair for the Hernándezes. They knew poverty, but they were rich in culture. Little Joe’s cousin David Coronado had already brought him into his band, David Coronado and The Latinaires. His younger brother Jesse Hernández joined after their first recording in 1958, followed by even more Hernández brothers, Johnny and Rocky. After Coronado left, the band became Little Joe and The Latinaires through the 1960s and changed again to Little Joe y La Familia in the ’70s.

NBC News caught up with Little Joe over a celebratory breakfast with friends at Chevy’s Mexican Restaurant in Arlington, Virginia, for a look into his life and music and the making of an unlikely and uniquely American international phenomenon. Below is a condensed and edited version of the conversation.

What do you think about this new wave of regional Mexican music like Peso Pluma, Grupo Frontera and others?

“Each generation brings their own mix to the table. I’m always happy to see innovation in music. It’s a way to express one’s emotions, raíz, cultura, so the new music that we hear now on the Latino side, I think it’s great that we have it. From there, others will learn and develop their own music.”

You signed with other labels, but you also created your own labels, Buena Suerte Records for Spanish and Good Luck Records for English. How did that work out for you?

“In 1968 I was offered a contract with Capitol … and just the first paragraph of it said they would control everything and own everything. I had just started my [own] record company, and I wanted to produce the music that I’d produced through the years. There weren’t any outlets for Chicano music that was like my band [or] record labels to record my style of music, so I went independent. I produced my own recordings of my group and produced some 20, 25 bands.

“I understood the promotion and distribution … that if they didn’t do it for me I would do it myself. I learned how to put a group together, get the music, go into the studio, record it, then produce the music and have the albums pressed and the distribution and the promotion. The hard part came when the time came to collect.” (He smiles.)

How has your life informed your music?

“My dad and brothers and sisters were all musicians, played instruments, wrote songs, and they all sang. ... I had the advantage as a kid to learn so many great, beautiful songs, profound lyrics, haunting melodies. Every time I put out one of those songs, the acceptance was great. The song ‘Por Un Amor’ was an incredible hit for me, and then later on I re-recorded it into an album. And [it] went national and then went to Mexico and South America.

“But it’s [about] the deliverance; we all need rice and beans and tortillas, but it’s how they’re prepared, you know? Same thing with music, the arrangements of the song and, above all, the sentimiento [feeling], the feeling that we convey to people.

“I had soooo much material even before I started writing my own. I grew up listening to the big band era, the crooners, the swing bands. So in my music you have those overtones. In ‘Por Un Amor’ you hear the rock and roll; in ‘Cuando Salgo A Los Campos’ you hear the country; in ‘Qué Culpa Tengo’ you hear the jazz. ‘Ella’ is a mariachi song, a Mexican ranchera, but I feel it as a blues song, because I grew up with the blues, so that’s the way I delivered it. ‘Prieta Linda’ [is] slow, laid-back blues.“

You’re a little humble about your singing talent. You’re a very passionate and dramatic singer; I think your audiences love that. And I don’t know anyone who can belt out gritos like you do!

"Music is magic! Music is the only art form that can make a 10-month-old baby stand up and dance or a 90 year-old, because es algo del alma, something from the soul. It takes a level of talent to deliver [music], to produce it, but the feeling — that’s different. I’m able to deliver that feeling. … It doesn’t necessarily make you a great musician — maybe a great conduit to the heart and soul of the people.

“And a grito es un sentimiento [feeling], you know? Ouch! It hurts so good.” (He chuckles.) “It just feels so good. And to be able to convey that to the souls of other people, that’s my gift.”

What were some of the significant moments in your career?

“The death of my younger brother [Jesse], who played bass in the group with me. He died in a car accident at the age of 20 [in 1964]. ... He actually got me to quit my day job and really concentrate on booking the band. He foresaw this for me. … [When] we were having problems with a drummer, he said: ‘Joe, don’t worry about that. When you make a name for yourself, you’re gonna have musicians getting in line wanting to play for you.’

“When Jesse died I promised him that I would take the music to the top, whatever the top is, and I would stay with it, no matter what. I’ve seen others give up. … I was not about to quit. I made that promise to him.”

What do think Jesse would be saying to you now?

“I told you!”

You’re also a role model as a migrant farmworker.

“It was a really difficult time, but I came from something really special: my dad and mom, esa sangre [that blood], fighters, tough people, you know, hard-working people with good hearts. And I can say that for all my brothers and sisters.

“Music has taken me all over Europe, all over Japan, parts of Mexico and all over the United States, but more importantly it’s given me the podium to speak to issues of the communities. And that’s what keeps me going. That energizes me, [being] able to speak on behalf of people that can’t speak for themselves. That’s part of what I’m supposed to do.

“Familia means everything to me. Not just my family … or the musicians working with me. We’re just human. It really doesn’t matter where we come from. It’s what we do for one another.”