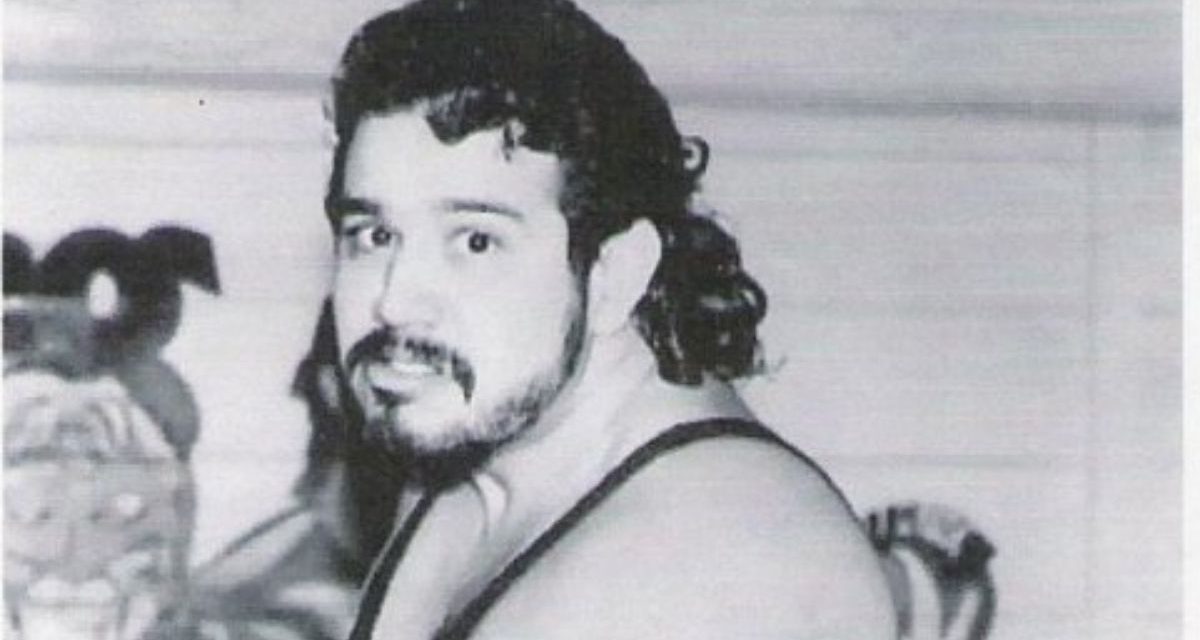

“Pistol” Pete Marquez, one of the hard-working grapplers from the Los Angeles territory of the 1970s and 1980s, who moonlighted in acting, has died. He was 65.

It had been a battle over the last little while, said his daughter, Sonia Marquez. He’d had a couple of strokes over the years, and was diabetic, and then another stroke about a month ago, where Pete lost the ability to swallow. “Then he ended up getting an infection after that, and the infection just took over his whole body,” Sonia told SlamWrestling.net.

The family had been told to expect the worst a week ago, but Marquez kicked out again and again. He died on April 13, at 6:34 p.m. in a Los Angeles hospice. “It’s crazy, because it was his mom’s birthday,” said Sonia. “It’s so him to die on his mom’s birthday, you know?”

Marquez was born on February 24, 1956, in Douglas, Arizona, but his formative years were in Los Angeles, where he went to Huntington Park Senior High.

In a 1990 Los Angeles Times feature detailing some of his acting gigs — Former Wrestling Villain Grapples With New Role — Marquez noted that he spent much of his youth in Los Angeles gangs.

“I didn’t have to prove myself by shooting someone,” Marquez told writer Michael Arkush. “I had wrestling.”

The nearby YMCA was a haven, a place to work on his physique and learn grappling. At age 18, the 6-foot-2, 280-pound Marquez became a professional wrestler, debuting on June 14, 1974.

“My uncle was a boxing trainer, he worked with a lot of people,” said Sonia. “They tried to get my dad to go into boxing. But no, he loved wrestling. It was Freddie Blassie. That was his idol. So that’s why he got into wrestling. And he just he loved it ever since he was a little kid.”

“Pete was 15 and living with his family in South Central L.A. when his interest in pro wrestling was sparked,” said Los Angeles wrestling historian Rock Rims. “His grandmother was a passionate fan who hated Freddie Blassie. Pete knocked down a shed in his mom’s backyard and used the wood to make a ring, inviting the neighborhood guys to come over and wrestle him.”

In the Times article, Marquez said, “It was fun; it was always at night, and I made good money.”

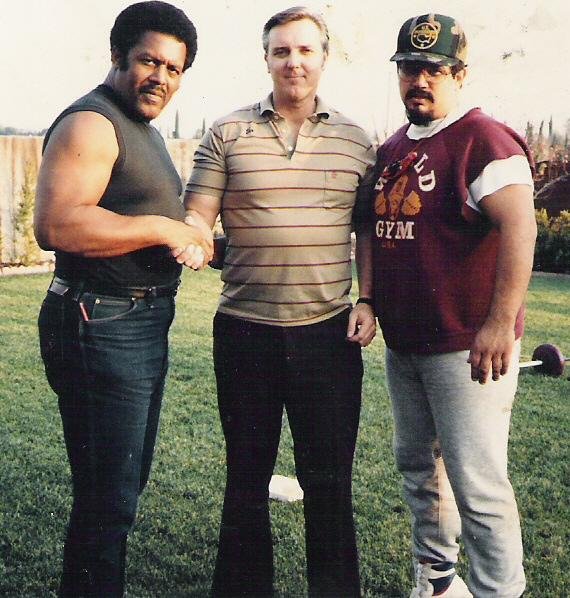

Buddha Khan, Doug Anderson and Pistol Pete Marquez.

You won’t find “Pistol” Pete Marquez, or his other name, Pedro Marquez, at the top of many cards. His best run came alongside one of his best friends, Buddha Khan (Eddie Carter), as tag team champions in Los Angeles.

“I was 10 years old when Pete began wrestling in Southern California for promoter Mike LeBell,” said Rims, author of Legends & Icons: A History of Olympic Auditorium and Southern California Professional Wrestling. “He was strictly prelim, but I never thought less of him, like some fans do upon those whose job it was to lose. He played a vital role in helping the stars shine. Back before they had wrestling figures, I used to make paper doll figures of some of the wrestlers in the territory. Along with Chavo Guerrero, Roddy Piper and Mil Mascaras, among others, I also made one of Pete. To me, he was an essential part of the territory.”

Marquez’s son, Marquez Jr., recalled being a lone voice in the crowd. “He was that journeyman, he was the one that got other people over,” he said. “Watching him in the ring, the crowd’s booing him, and I’m the only one cheering him.”

It was the same in the movie business. Marquez was in a number of films, but not in a leading role. He was The Sphinx in the TV version of Weird Science, The Sidewinder in Bad Guys, and, naturally, a wrestler in both Body Slam and Grunt! The Wrestling Movie. The Times article coincided with a small stage production in Burbank, The Curse of the Mummy’s Purse, where he played a pagan priest. “It’s a lot like wrestling,” Marquez said in the Times. “You have to entertain the audience, and show emotions to a crowd.”

There were behind-the-scenes jobs too, such as working as a stunt coordinator.

Or helping train the GLOW girls.

“We used to have a wrestling ring in our backyard. I remember when he would help train the GLOW girls with Mando [Guerrero],” said Sonia. “And then the Wild Samoans would be in our backyard. It was really pretty cool.” Naturally, if Pete was there, so was Khan as well, helping teach the aspiring female wrestlers.

Marquez Jr., who is also the oldest of Marquez’s kids, recalled realizing that his father had a different job than most. “In second or third grade, we had a parent teacher conference night, and one of my friends went up to him, and asked him for his autograph. And so he signed the autograph for him. And then before I knew it, there was a whole line of kids waiting to get his autograph,” chuckled Marquez Jr. “That was the first hint to me that he was different from other parents.”

That ring in the backyard of their home in Hacienda Heights, a suburb of Los Angeles, was irresistible said Marquez Jr. “The second the ring was free, I climbed in there, went to the top rope, did the Superfly splash into the middle of the ring.”

As a father, Marquez could be tough. “He wanted us to understand that life isn’t perfect,” said Marquez Jr. “He did everything he could to help us be independent. … he was in a gang and he used wrestling to get out of the gang — that was his way out. And he took it. And so he made sure that we were aware of the dangers out there. And he was all about protection, and just teaching us and making sure we knew what kind of world was out there.”

Marquez spent 25 years as a wrestler, and worked as a promoter with California Championship Wrestling. Besides wrestling and acting, he was a machinist, and served for a time as the financial secretary for the International Machinist Union Local 177.

Both his faith and charity was important too, and Marquez gave time to Guiding Eyes of America, March of Dimes and the City of Hope Fund Raiser. Special needs children could always count on his father, said Marquez Jr. “We’d go and he’d meet with these kids. And he’d teach them a couple of holds here and there, and talk to them and play with them. And, and he was always doing stuff like that visiting kids, special needs kids.”

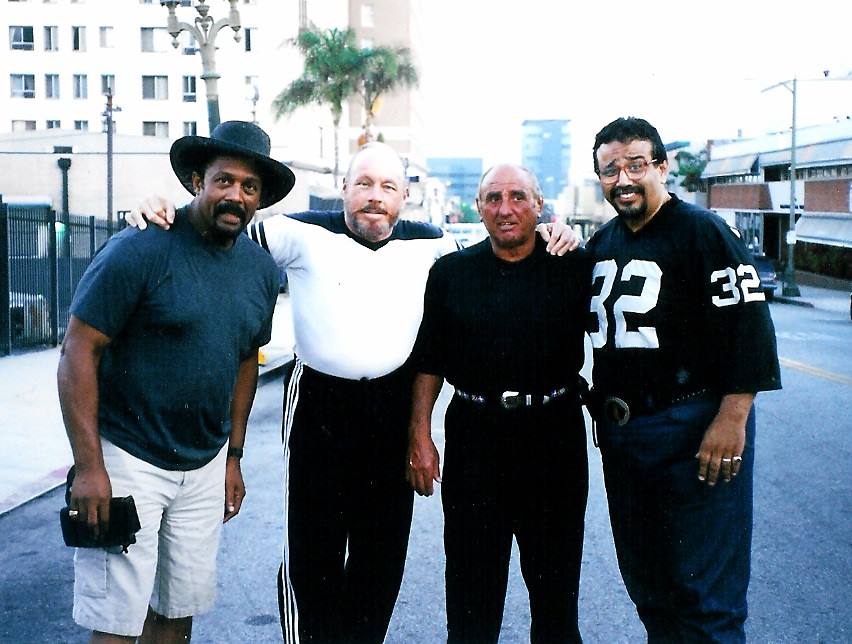

Buddha Khan, “Wildman” Jack Armstrong, Tony Rocco and Pete Marquez.

Marquez was also among the regulars at the Cauliflower Alley Club (CAC) reunions that were held in Los Angeles. When the CAC events moved to Las Vegas, he would be there too, usually alongside his buddy Khan, laughing and reliving good times. Sonia said that Khan, who died in 2018, was like an uncle to the four Marquez kids.

Those wrestling meet-ups were important to her father, said Sonia. “He loved reminiscing.”

Or, as Marquez himself noted on his active Facebook page, “It’s better to be a ‘Has Been’ than a never was!”

Marquez’s second marriage, to Martha Escarcega Marquez ended in divorce. The couple had four children: Pete Jr., Vanessa, Michael, and Sonia.

Funeral arrangements are still being finalized.