Fatherhood has been much on Stephen Mangan's mind lately. Partly it's as a result of rehearsals for a new play in which he dons a latex pregnancy suit and has to feign going into labour. In Birthday by Joe Penhall, at the Royal Court, London, opening this week, Mangan stars as a man with an artificial womb and spends much of his time on stage "yelling and screaming and grunting".

"It throws an interesting light on what each gender has to go through," Mangan says drily when we meet in his local pub in Primrose Hill, north London. "I was there when our two kids were born [Harry, four, and one-year-old Frank, with his actress wife Louise Delamere] but I never imagined when I was watching it unfold that I'd be on the bed one day."

Mangan, 39, is an actor best known for his comic turns. He is now starring as a put-upon screenwriter in BBC2's sitcom Episodes, opposite Tamsin Greig and Matt LeBlanc, and made his name in the TV adaptation of Adrian Mole: The Cappuccino Years before going on to play the obnoxious Dr Guy Secretan in Channel 4's cult comedy Green Wing.

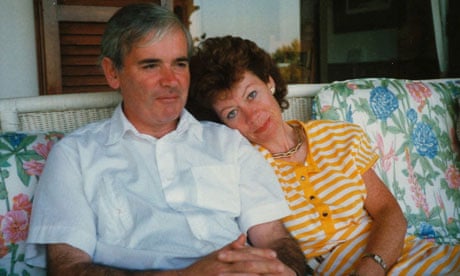

But private grief has been a counterpoint to his professional success: his parents, James and Mary, both died of cancer before they got to meet their grandsons. In 1991, Mary Mangan died of colon cancer, six months after she was diagnosed. She was 45. Fourteen years later, Stephen's father was found to have a brain tumour. His disintegration was similarly swift and brutal: after six months, he was dead at the age of 63.

"When Dad got ill, I just thought: 'Really? Again?'" Mangan says now. "He died when I was in my early 30s. We were filming the second series of Green Wing in a real hospital, then I'd go to another hospital to see him. They shut down the whole production at the end so I could be with him, for which I'm incredibly grateful."

Mangan has, by his own admission, always been wary of sharing too much, of devaluing the currency of his memories by speaking about them publicly. But this month he is supporting a new series of guides aimed at children who have a parent or close family member with cancer. The pamphlets, I Know Someone With Cancer, produced by the private healthcare company Bupa, include a glossary of medical terms, suggestions of how to help out around the house and advice about what might change at home after a diagnosis.

"I have kids now and I find it hard to imagine having to talk my children through that or explain to them what is going on if I got ill or my wife got ill," Mangan says, pouring milk into a cup of tea that will sit, untouched, for much of the interview. His mother's brother died of colon cancer a couple of months ago and Mangan has watched his cousins "cope with exactly the same things I went through: trying to deal with doctors, making sense of what's going on, how suddenly you have to look after the person that's always looked after you. It's a discernible, head-spinning, sudden change in the set-up of the family."

The necessity of parenting his own mother and father through their illnesses was, he says, one of the hardest things to deal with. "To say you grow up is a bit trite. You become an adult is a better way of putting it."

Mangan and his two younger sisters grew up in an "incredibly loving" home in Ponders End, north London. His parents were Irish, born and raised in rural Co Mayo in large Catholic families: his father was one of nine; his mother one of seven. Both came from impoverished backgrounds ("It wasn't Angela's Ashes," he says, "but not a million miles from it") and left school at 14 before emigrating to London. James worked as a builder. Mary got a job at a bar in Camden where the two of them met. Mangan grins: "That bar is now an Indian restaurant."

His mother, he says, was "really sunny, very warm, a very natural mother… she was the centre of her family". His father was "very sharp, bright, a really funny guy. He had a real talent for living. Some people are just good at it."

Although his parents had never had much of an education, Mangan surprised everyone by winning a scholarship to Haileybury public school in Hertfordshire, and becoming a boarder, before studying law at Cambridge – the first member of his family to go to university.

"They were really freaked out by the idea," Mangan recalls with a snort of laughter. "I think some people rebel by slamming doors and telling their parents to shove it up their arse. I could never do that. My rebellion was to get away… my family was fantastically loving but it's almost too much when you're 13." His mother fell ill shortly after Mangan graduated. There is a photograph of the two of them taken the day he got his degree by the Senate House in Cambridge – Mangan in his academic gown, with an unruly mop of hair; his mother immaculately dressed in a pinstriped jacket, smiling steadily at the camera.

Looking back at that picture, Mangan realises that his mother would already have been ill.

"I left university in June and we got the news in early September," he says. "So it was quite an easy decision for me to say, 'I'm not doing anything, I'll stay at home'."

He took the best part of a year off to look after her, driving her to radiotherapy sessions at Barts hospital and the London Clinic. Having been away for so much of his adolescence, he was "delighted to be able to be there. I felt I'd missed out on a lot of home life."

The treatment, however, was horrible, he says. "She really degenerated physically in an alarming way. By the end she was almost skeletal. She didn't speak for the last two or three weeks. She was incredibly weak. To see someone so healthy – she didn't smoke, she didn't drink, she ate well – and so young – she was 45 years old, to see someone like that become…" He drifts into silence. "I don't know. You just deal with it on a daily basis, this freakish news, this big situation… You have a slow-motion mourning for six months. The news starts to sink in, piece by piece and the brutality of it is drip-fed to you in a way so you can't get that violent hit in one go."

With his father, witnessing the indignity of his illness was bewildering, Mangan says. "He just became a bit confused, slowly his brain just started to shut down," he says and for the first time since we have started speaking, his eyes acquire a gloss of moisture. He looks away, fixing his gaze on the mid-distance, knitting his fingers together to stop them from shaking. "There were episodes of paranoia and hallucination. He became childlike – he lost all his hair so he was this slightly shrunken, bald guy. If I'd suddenly turned up one day and seen him, it would have freaked the shit out of me.

"I remember, one day, washing him with a flannel. Just, you know, your dad, this big, strong guy who has always looked after you. To see him like that…" Again, words fail him.

"But I got a really good deal," he says, visibly pulling himself together, "because they were really incredible, amazing parents: loving, funny. So, if that's the story, that's the story. I'd rather have that than for them to have lived to 95 and for us to hate each other."

He has a lasting regret, picked out from the vast, inexpressible void of things left unsaid or undone: "I never got to know Mum as an adult. You get to know your parents differently as you get older."

Her death prompted a crisis of faith – Mangan was raised a Catholic and was an altar boy, but, as he puts it: "When you watch someone die, all you want is for it not to be the end of it, for it not to be what it looks like it is… When you see someone going into a hole in the ground, you don't want to cope with that being the end of the story. I can totally understand why so many religions provide a 'get out of jail free' card but I just don't believe that."

It also changed the direction of his life. Although his degree was in law, he decided to pursue his love of acting – at university, he had thrown himself into amateur dramatics and his contemporaries included film star Rachel Weisz and comedian Sue Perkins.

"The fact that she died and died young – I thought 'You know what? I'll give it a go' because if I've got 20 years left, I want to spend it doing something I love," Mangan says.

He had his final audition for Rada 10 days after his mother's funeral, graduating in 1994 before cutting his teeth on stage in a series of theatrical roles, including a successful stint with the Royal Shakespeare Company.

Now that Mangan has a family himself and is approaching the age his mother was when she died, he is keenly aware of his own mortality. He and his sisters, Anita and Lisa, have checkups every two to three years – the colon cancer that killed his mother and uncle can be hereditary.

"I had a colonoscopy a couple of months ago," he says. And then, in case there were any room for doubt, he adds cheerfully: "Yeah, I had a camera shoved up my arse."

He grins. Sometimes, the only thing left to do is laugh.

The booklets can be downloaded at bupa.co.uk/individuals/iknowsomeonewithcancer

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion