Spencer Perceval, born on 1st November 1762, was a trained lawyer who later entered the world of politics and served as British Prime Minister from 4th October 1809 until his death on 11th May 1812. Unfortunately for Perceval, he was not to be remembered for his service to the politics but rather his ill-fated ending, the only British Prime Minister to be assassinated.

Perceval was born in Mayfair to John Perceval, the 2nd Earl of Egmont and Catherine Compton, also known as Baroness Arden, the granddaughter of the 4th Earl of Northampton. He came from a titled, wealthy family with political connections; he was after all named after his mother’s great uncle, Spencer Compton who had served as Prime Minister. Meanwhile, his father worked as a political advisor to King George III and the royal household. This naturally held him in good stead for his future career in politics.

Upon leaving Cambridge, Perceval embarked on a legal career, entering Lincoln’s Inn and completing his training. Three years later he was called to the bar and joined the Midland Circuit, using his family credentials to acquire a favourable position.

Meanwhile, in his private life, both he and his brother had fallen in love with two sisters. Unfortunately whilst his brother’s marriage to Margaretta was approved by the father, Spencer was not so fortunate. Lacking a title, considerable wealth and highly acclaimed career, the couple were forced to wait. The two lovebirds were left with little choice but to elope. In 1790 Spencer married Jane Wilson, who had eloped on her twenty-first birthday, a decision which proved fruitful as they would end up having six sons and six daughters in the next fourteen years together.

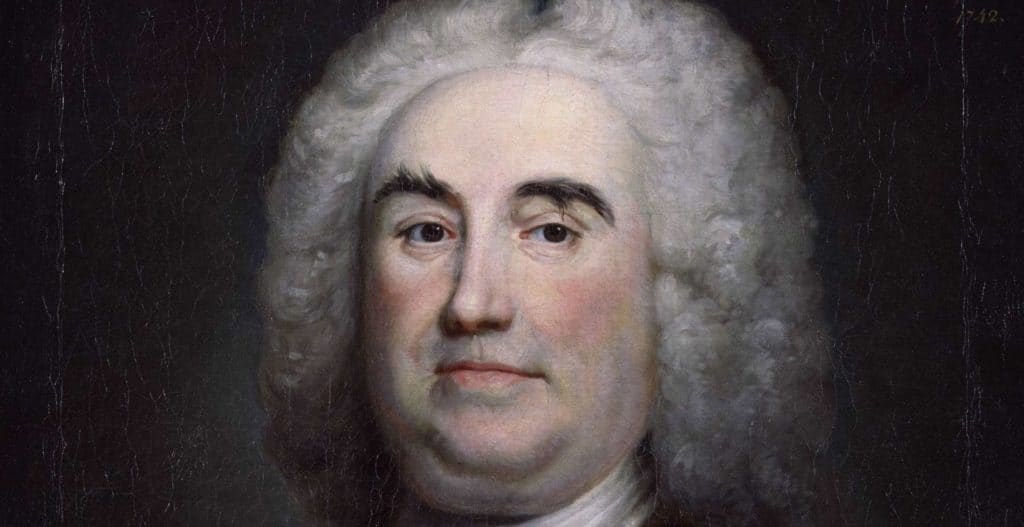

Perceval meanwhile was in the midst of trying to establish himself as a legal professional and served in many roles, acquired due to his family connections. In 1795 he finally found himself gaining more recognition when he decided to write an anonymous pamphlet advocating the impeachment of Warren Hastings who had been Governor-General of India, well-known for his misdemeanours. The pamphlets written by Perceval won the attention of William Pitt the Younger and he was offered the position as Chief Secretary of Ireland.

Whilst Perceval turned down this enticing offer in favour of more lucrative work as a barrister, the following year he became a King’s Counsel with a salary amounting to £1000 a year (£90,000 today). This was prestigious for a man who was one of the youngest ever to have this role.

Perceval’s political career grew from strength to strength, as he was appointed Solicitor General and later Attorney General under Henry Addington’s administration. Throughout his career he maintained largely conservative views, steeped in Evangelical teachings. This proved decisive in his support for the abolition of slavery, alongside his compatriot William Wilberforce.

In 1796 Perceval entered the House of Commons when his cousin, who had been serving the constituency of Northampton, inherited an earldom and entered the House of Lords. After a contested general election, Perceval ended up serving Northampton until his death sixteen years later.

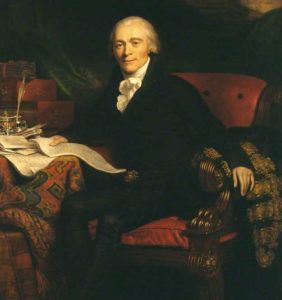

When William Pitt died in 1806, he resigned from his posts as Attorney General and became the leader of the “Pittite” opposition in the House of Commons. Later, he would end up serving as Chancellor of the Exchequer, a position he held for two years before becoming Prime Minister on 4th October 1809.

During this time Perceval had many a daunting task, principally dominated by the Napoleonic wars with France. He needed to secure the necessary funds, and also expand the Orders in Council which encompassed a series of decrees designed to restrict other neutral countries trading with France.

By the summer of 1809, further political crisis led to his nomination as Prime Minister. Once leader, his job did not get any easier: he had received five refusals in his bid to form a Cabinet and eventually resorted to serving as Chancellor as well as Prime Minister. The new ministry appeared weak and heavily reliant on backbench support.

Despite this, Perceval weathered the storm, dodging controversy and managing to put together funds for Wellington’s campaign in Iberia, whilst at the same time keeping debt much lower than his predecessors, as well as his successors. King George III’s ailing health also proved to be another obstacle for Perceval’s leadership but despite the Prince of Wales’ open dislike of Perceval, he managed to steer the Regency Bill through parliament.

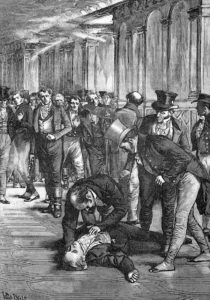

In 1812, Perceval’s leadership came to an abrupt end. It was evening time, around five o’clock on 11th May 1812, when Perceval, needing to deal with the inquiry into the Orders in Council, entered the House of Commons lobby. There waiting for him was a figure. The unknown man stepped forward, drew his gun and shot Perceval in the chest. The incident happened in a matter of seconds, with Perceval falling to the floor, uttering his last words: were they “murder” or “oh my God”, nobody knows.

There was not enough time to save him. He was carried to the next room, pulse faint, his body lifeless. By the time the surgeon had arrived, Perceval was declared dead. The sequence of events that followed was dominated by fear, panic regarding motive, and speculation as to the identity of the assassin.

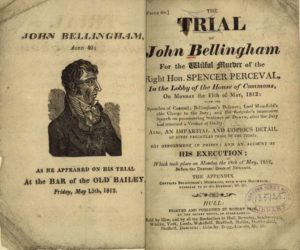

This unknown figure had not attempted to escape and it was soon found out he had acted alone, allaying fears of an uprising. His name was John Bellingham, a merchant. Bellingham had sat quietly on the bench whilst Perceval’s breathless body had been carried into the Speaker’s quarters. When he was pressed for answers, a reason for this assassination, he simply replied that he was rectifying a denial of justice committed by the government.

The Speaker gave orders for Bellingham to be transferred to the Serjeant-at-Arm’s quarters in order for a committal hearing to be conducted under Harvey Christian Combe. The makeshift court used MPs who also served as magistrates, listening to eyewitness accounts and giving orders for Bellingham’s premises to be searched for further clues as to his motivation.

The prisoner meanwhile remained completely undeterred. He did not heed the warnings of self-incrimination, instead he calmly explained his reasons for committing such an act. He proceeded to tell the court how he had been mistreated and how he had attempted to explore all other avenues before turning to this choice. He showed no remorse. By 8 o’clock in the evening he had been charged with the Prime Minister’s murder and taken to prison, awaiting a trial.

The assassin turned out to be a man who had been unjustly imprisoned in Russia. Bellingham had been working as a merchant, dealing with imports and exports in Russia. In 1802 he had been accused of a debt amounting to 4,890 roubles. As a result, when he was due to return to Britain, his travelling pass was withdrawn and he was later imprisoned. After a year in a Russian prison, he secured his release and immediately travelled to Saint Petersburg to impeach the Governor General Van Brienen who had been so instrumental in securing his imprisonment.

This angered the officials in Russia and he was served with another charge, resulting in his further imprisonment until 1808. On release, he was pushed out onto the streets of Russia, still unable to leave the country. In an act of sheer desperation he petitioned the Tsar and eventually returned home to England in December 1809.

Upon his arrival back on British soil, Bellingham petitioned the government for compensation for his ordeal but was met with a refusal because Britain had broken its diplomatic relations with Russia.

Despite begrudgingly accepting this, three years later Bellingham made further attempts for compensation. On 18th April 1812 he met a civil servant at the Foreign Office who advised Bellingham that he was at liberty to take whatever measures he felt necessary. Two days later he purchased two .50 calibre pistols; the rest is history.

Bellingham, a man intent on justice, targeted the man at the top. After serving for just a few years as Prime Minister, Perceval died leaving behind a widow and twelve children. On 16th May he was buried in Charlton at a private funeral and two days later Bellingham met his fate; he was found guilty and hanged.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.