Shuttlecock (film)

| Shuttlecock | |

|---|---|

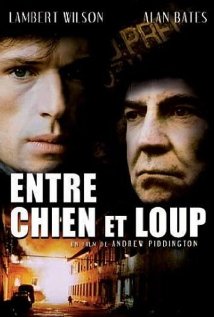

film poster | |

| Directed by | Andrew Piddington |

| Written by |

|

| Based on | The novel of the same name by Graham Swift |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by | |

Production companies |

|

Release date |

|

Running time | 85 minutes |

| Countries |

|

| Language | English |

Shuttlecock is a 1993 French-British thriller film directed by Andrew Piddington and starring Alan Bates, Lambert Wilson and Kenneth Haigh.[1] It is based on the 1981 novel Shuttlecock by Graham Swift.[2][3]

Plot[edit]

Major James Prentis (Alan Bates) is a British spy of World War II and war hero[4] who goes under the code name of "Shuttlecock". Alienated from his family and children, he ends up in a mental institution in Lisbon, Portugal, where he eventually decides to publish his memoirs 20 years after the war. His son, John (Lambert Wilson), becomes increasingly alarmed with the enigmatic Dr. Quinn (Kenneth Haigh), the director of the institution, and concludes after reading his father's memoirs that Quinn is responsible for his father's mental decline.

Cast[edit]

- Alan Bates as Major James Prentis VC

- Lambert Wilson as John Prentis

- Kenneth Haigh as Dr. Quinn

- Jill Meager as Marian Prentis

- John Cassady as Eddie

- Arthur Cox as Fizz / Fox

- David Ryall as Pound

- Gregory Chisholm as Martin Prentis

- Beatrice Buchholz as Beatrice Carnot

- Jacqui Sedlar as Jenny

- Dominic Chesterton as Peter Prentis

- João Perry as Eric

- Luísa Barbosa as Ana

Production[edit]

The production for the film was marred with problems, which resulted in a long delay in release.[5] Producer Graham Leader acquired the rights to the film in the late 1980s after a meeting with Graham Swift, the writer of the novel, and paid $7,500 for the rights over two years.[5] Tim Rose Price, the writer of several BBC dramas, agreed to write the script, and worked on a script with Leader throughout 1989. Jon Amiel agreed to direct. Producers Leader and Charles Ardan approached Channel 4 and British Screen to finance the picture; Channel 4[6] agreed to shout $900,000, payable when the film was completed, and British Screen offered just over $500,000, if Leader could attract a co-producer on the European continent who could finance $1.5 million.[5] Leader had searched for financing in the United States, but was turned down by the likes of Orion Classics and Avenue Pictures, who wanted the characters and settings Americanized. French independent French company Les Productions Belles Rives eventually agreed to partly finance the film.[5] After one of France's largest film labs conceded to provide materials and film-processing services, a shortfall of $225,000 still remained.[5]

The film was shot on location in Lisbon, Portugal over six weeks at the end of 1990 and beginning of 1991, with a French, English and Portuguese crew. Producer Leader described the filming for Shuttlecock as "highly unorganized chaos", and the actors were surrounded with confusion on set.[5] Financing was halted during the filming when a French bank which had loaned the money for production "decided to take its fees out of the loan rather than out of the profits from the film". To get themselves out of difficulty, producers Leader, Piddington and Rose put half of their fees for it back into the film.[5] A British investor turned up during the filming, promising to provide financing, but a New Zealand heiress froze all of his bank accounts before anything was signed. Filming was wrapped up in January 1991 in London, before post-production began at Pinewood Studios.[5] The total budget eventually amounted to around $3 million.[5]

The film was screened at the San Sebastian Film Festival, shortly after a rushed job with adding Spanish subtitles, where it failed to win the $250,000 Golden Shell Award and any others, making it ineligible for Cannes. Further editing to the film over the next six months was done, but the producers failed to attract a distributor.[5] There was optimism for a time that it would be released at the Hamptons International Film Festival, but it amounted to nothing.[5] Financing for the film was eventually derived mainly from Channel 4, Les Productions Belles Rives, and KM Films,[7] and a plethora of other associate producers such as Sea Lion Films, Gigantic Pictures, Minerva Productions, and distributors such as Alliance Communications, Le Monde Entertainment, and Movie Screen Entertainment.[8]

Reception[edit]

The film received a mixed response from critics. Variety praised the film's acting and directing but stated that its "theatrical prospects seem iffy."[5] The cinematography of the film was praised by some critics. Sight & Sound magazine wrote that "Andrew Piddington approaches his material in a resourceful way."[9] Richard Schickel, the film critic for Time, reportedly approved of the film when he first viewed it, but several years later described it as "a bit on the plodding side" and as "the kind of film that would have two weeks in the theater and then go straight to video."[5] The New York Times considered the film to be a disaster, writing:

"Shuttlecock" is a film for which things went very wrong. So wrong, in fact, that it makes a kind of negative case study for anyone thinking of investing in or producing an independent film. Its troubled history is a whole-earth catalogue of bad decisions, strategic miscalculations, painful rejections, misunderstandings and lots of old-fashioned bad luck. It is the film story that independent producers pray they will never live through.[5]

However, when the film was screened on 6 January 1994 on Channel 4 as part of its series "Film on Four", the Sunday Telegraph named the film its "TV Pick of the Week," referring to it as "a film with things to say and a muscular yet sensitive way of saying them."[5]

The film has been remade under the title "Sins of a Father", reported the New York Times Feb. 1, 2015.

References[edit]

- ^ "Shuttlecock". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 14 January 2009. Retrieved 16 September 2014.

- ^ Livres hebdo (in French). Éditions professionelles du livre. 1992. p. 98.

- ^ The Hollywood Reporter. Wilkerson Daily Corporation. 1992. p. 50.

- ^ Fiches du cinéma: Annuel (in French). L'Office catholique français du cinéma. 1991. p. 136. ISBN 9782902516094.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Grimes, William (13 February 1994). "FILM; Filming Turns Out to Be Just the Beginning". The New York Times. Retrieved 16 September 2014.

- ^ Gallix, François (2003). Graham Swift: écrire l'imagination (in French). Presses Univ de Bordeaux. p. 115. ISBN 978-2-86781-312-2.

- ^ Film and Television Handbook. The Institute. 1992. p. 261. ISBN 9780851703176.

- ^ Film Directors. Lone Eagle Publishing. 2002. p. 197. ISBN 9781580650434.

- ^ Sight and Sound Film Review Volume. BFI Publishing. 1993. p. 250. ISBN 9780851704821.