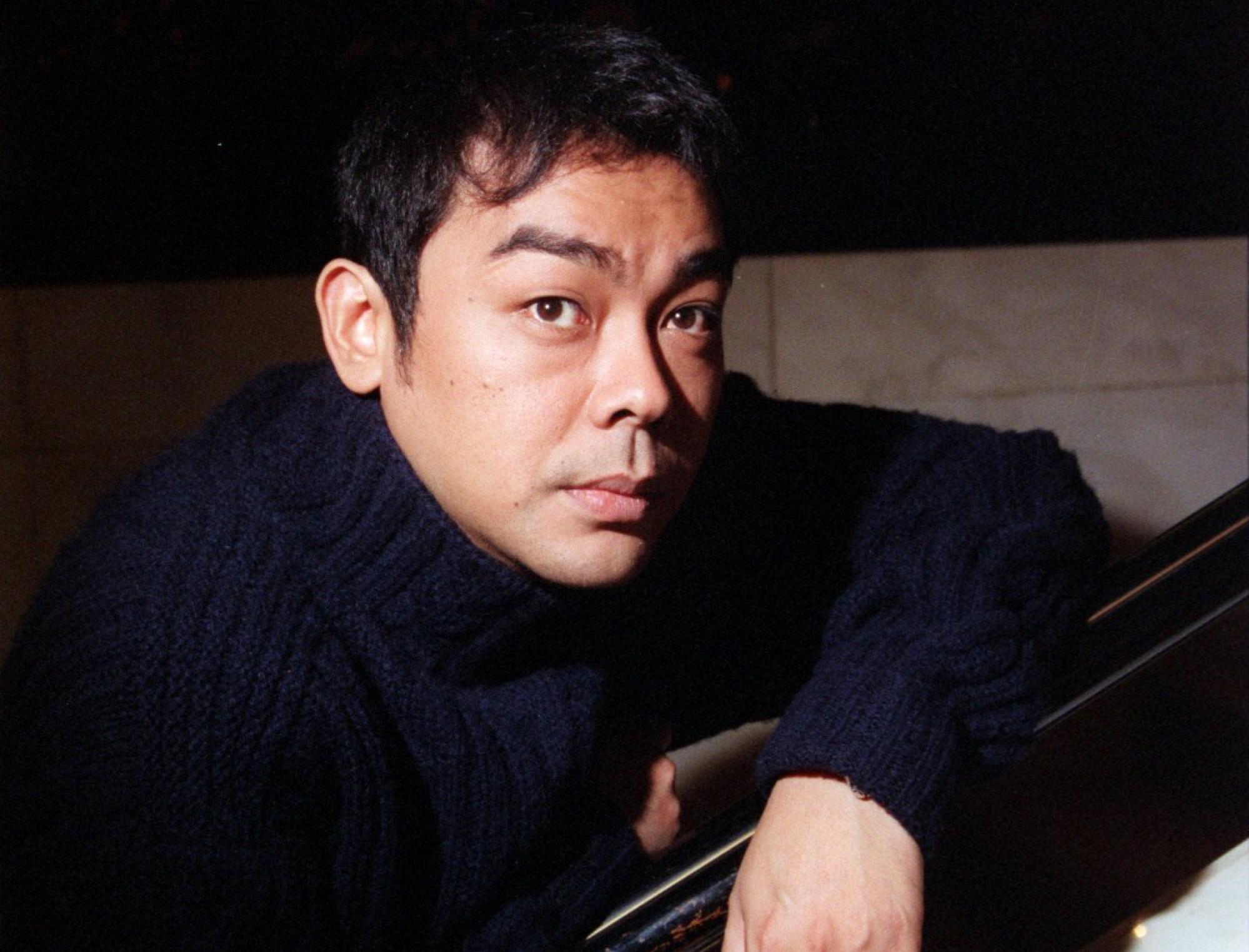

‘I am not Jackie Chan or Chow Yun-fat’: Hong Kong actor Lau Ching-wan on why Hollywood doesn’t need him, bad guy roles, and The Godfather

- Hong Kong actor Lau Ching-wan, often credited as Sean Lau, has adopted many roles in the years that he has been acting – and most have been heroic ones

- In a 1998 interview, he revealed the scenes he will never do, which movie he has seen more than 100 times and why films are easier than TV shows

It was in the mid-1990s that Hong Kong actor Lau Ching-wan became a member of the unofficial stock company at director Johnnie To Kei-fung’s innovative Milkyway Image production house.

“In a city that often pigeon-holes its performers, Lau Ching-wan has become noted for his versatility. Action, drama, romance, comedy, he has done the lot,” effused the Post in 1998.

The following interview took place with this writer during a break in the filming of To’s 1998 gangster drama A Hero Never Dies.

You’ve played many different types of characters. Did this variety come about by accident or design?

I like to be different. I don’t like to play the same character over and over again.

Usually in Hong Kong, you don’t get the choice. If you start off playing a police officer, for instance, you tend to stay a police officer.

But I’m most satisfied when I’m doing something new, and luckily my producers have supported me in this.

These films made Stephen Chow famous before Shaolin Soccer, Kung Fu Hustle

Except for the killer in The Longest Nite, you’ve always played heroes. Do you want to play more villainous roles?

Yes, Ringo had me in mind for the bad guy, but he decided against it, and I ended up playing the hero instead. He realised that if I was the villain I would have to die, and I wouldn’t be able to appear in a sequel. So he got me to play the good guy.

You trained at the TVB drama school, and spent 10 years working in television. Did that experience help prepare you for films?

Working in television was a good exercise. You get a lot of opportunities to experiment. I worked on many different kinds of programmes. But it was hard work. Every day the schedule ran from 6am to 2am. After doing that, making movies seems like an easy job – in fact, it seems like a very easy job!

What are your memories of C’est La Vie, Mon Cheri, the film that made you a star?

I have fond memories of that film. As a struggling actor at the time, I had a lot in common with the sax player.

How do you feel about shooting more than one film at a time?

Well, I’ve cut down on the number of films I make so that I can concentrate on my performances. Now I try to make just one film at a time, whereas I used to make two. I think it’s stupid to do that today. Actors only do that for the money. But sometimes it does hurt to pass on a character that I am offered. If a good character comes along, it always seems a shame to let it go.

Did you ever find working on two films at the same time confusing?

Not really – I’m a confused kind of guy anyway!

How do you feel about “flying paper” – the director making up the script during the actual shoot?

In some ways it makes my job easier as I don’t have to do much preparation. Take A Hero Never Dies. I know what the hero looks like and that’s all I have to go on. I know that I’m a killer, and that’s it. I’ll sort out the rest by talking to the director as we go along.

Without a script, there is a lot of room for me to make suggestions about how the character would act. But I do like to shoot films with a full script, too. For instance, Too Many Ways to be Number One had a good script. Director Wai Ka-fai was also the writer. I loved that script and I found it very interesting to act in the film.

What do you think of method acting?

It would be great to have more time to really get into the role and do method acting. But there is never time in Hong Kong for that kind of thing.

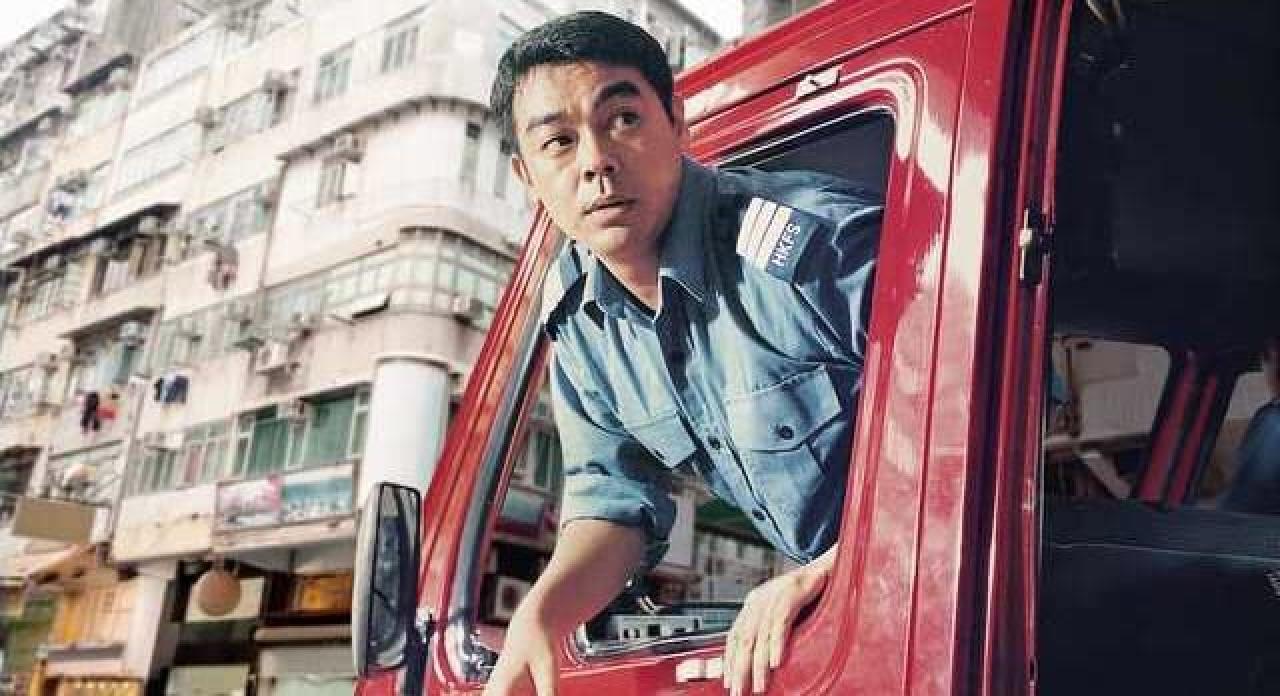

How did you get inside the mind of the grumpy police officer in Big Bullet?

It was quite simple. I just pretended to do his job and I became him.

Are there any performances you think you could have done better if you had more time?

I did have a problem playing the priest in Final Justice. The movie is OK, but I think I personally failed, as I don’t think I played the part very well.

I had to try and work out how a guy could give up everything to serve God. I kept thinking, how could he really give everything up to do this? What kind of guy does this? I asked some priests this question, but I didn’t really find out the answer. So I failed.

Which actors do you like to watch?

We studied a lot of Hollywood actors in training school. I especially like Robert De Niro and Al Pacino. I have watched The Godfather over 100 times! I also really like Taxi Driver.

Is it true you improved your English by watching The Godfather?

The first time I watched it, I read the Chinese subtitles. As time passed, and I watched it more, I realised that my English had got better, as I didn’t have to read the Chinese subtitles.

And nowadays I can translate the English dialogue back into Chinese as they are speaking it! So you could say that I can chart my progress in English through watching The Godfather.

What is it that you admire most about The Godfather?

For me, it’s Frances Ford Coppola’s direction. It made me want to become an Italian!

Would you like to appear in an American film?

Yes, I would like to work with someone like Martin Scorsese. I would like to play the kind of character Joe Pesci plays in Casino.

They have a big Asian market and so they can help the Americans make money. I don’t have that, so Hollywood doesn’t really need me.

In this regular feature series on the best of Hong Kong cinema, we examine the legacy of classic films, re-evaluate the careers of its greatest stars, and revisit some of the lesser-known aspects of the beloved industry.