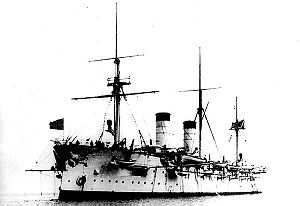

Russian cruiser Rurik (1892)

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Rurik |

| Namesake | Rurik |

| Builder | Baltic Works, Russia |

| Laid down | 31 May 1890[1] |

| Launched | November 1892[1] |

| Commissioned | May 1895 |

| Fate | Scuttled – 14 August 1904 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Armoured cruiser |

| Displacement | 10,950[1] |

| Length | 412 ft (125.6 m) |

| Beam | 67 ft (20.4 m) |

| Draught | 30 ft (9.1 m) (max)[1] |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion | 2 shafts; 2 vertical triple-expansion steam engines |

| Speed | 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph) |

| Range | 19,000 miles at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph); actual radius at full speed: 2,300 miles[1] |

| Complement | 768[1] |

| Armament |

|

| Armour |

|

| Notes | Coal capacity: 2,000 tons |

Rurik (Russian: Рюрик) was an armoured cruiser built for the Imperial Russian Navy in the early 1890s.[1] She was named in honour of Rurik, the semi-legendary founder of ancient Russia. She was sunk at the Battle of Ulsan in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–05.

Design and construction[edit]

The Imperial Russian Navy, by the end of the 19th century required a cruiser capable of undertaking long cruises into foreign waters for the purpose of destroying commercial vessels, especially if war was to occur between Russia and the United Kingdom. Russian admiral Ivan Shestakov submitted the design of Rurik to the Baltic Works at St. Petersburg for construction, bypassing the normal procedure of submitting the design to the Naval Technical Committee (MTK). The original specifications for the vessel, as submitted by Shestakov, are currently lost,[2] but presumably Shestakov intended the ship to be able to travel from "the Baltic to Vladivostok without recoaling en route".[2] It appears that Shestakov wanted a design similar to Pamiat Azova and such a design was submitted via a constructor from the Baltic Works to the MTK.

That design, a 9,000-ton, 8 inch belted cruiser, was rejected by the MTK. It is more likely that the design was rejected because of tension between Shestakov and the MTK and the General Admiral of the Navy, Grand Duke Alexei Alexandrovich, rather than technical issues with the design.[2] The submitted design called for a long warship (over 400 feet (120 m)) and had a design endurance of 20,000 nautical miles (37,000 km). Shestakov was unable, however, to fight for the submitted design, as he died in December 1888.

Shestakov's successor, Chikhachev, had excellent relations with the MTK board, and the Baltic Works design was quickly rejected. The MTK design which followed was a 10,000-ton vessel with a 10 inch belt and with an operational speed and range of 18 knots (33 km/h) and 10,000 nautical miles (20,000 km) respectively.[2] Rurik would also sport a complete barque rig. Construction began in 1890 after powerplant issues were solved by the technical designers at the Baltic Works.

As plans and designs of Rurik were being finalised, rumours began floating as to the exact nature of the vessel. In particular, Britain became extremely nervous about the new cruiser, fearing greatly for her large commercial fleet which she depended on. The British press "fuelled anxiety to the point where it approached paranoia."[2] As it turned out, the Royal Navy grossly overestimated the threat posed by Rurik[1] and built the cruisers specifically designed to counter the Rurik.[3] Two of the first ones were the Powerful and Terrible. The British cruisers turned out to be much faster, easily making 22 knots compare to the Rurik's top speed of 18.7 knots (34.6 km/h). The British cruisers were using the watertube, or coil, boilers that later were proved superior and became a standard on all new warships of that time.

While there was a heavy armament of four 8-inch (203 mm) guns and 16 6-inch (152 mm) guns, along with a quartet of 15-inch (381 mm) torpedo tubes, the armour for Rurik was light, with only an average 2.5 inches on the decks and an average 10 inches on the sides using nickel steel plate.

Service history[edit]

After her commissioning, Rurik headed for the Russian Pacific Fleet based at Vladivostok. Admiral Fyodor Dubasov, who commanded the Pacific Squadron, recommended various modifications to the ship after a short period of service, including reboilering and the removal of the ship's rigging.[2] The reboilering project never got off the ground, but the amount of rigging was cut down significantly.

When the Russo-Japanese War broke out in 1904, Rurik and the other cruisers of the Pacific Squadron, Rossia, Gromoboi, and Bogatyr, were all charged with seeking out and destroying Japanese merchant vessels in the Sea of Japan and along the coasts of the Japanese home islands. By August 1904, only one ship had been sunk and the Imperial Japanese Army had moved siege artillery close enough to shell the main Russian port in the Pacific, Port Arthur. The siege of Port Arthur kept most of the Russian naval vessels assigned to the Pacific Squadron inside the port, despite several failed attempts at breakout.

On 14 August, three of the four Vladivostok-based cruisers sortied towards Port Arthur (Bogatyr having received damage due to grounding[2] ) in an attempt to assist in lifting the Japanese blockade. They were met by a squadron of Japanese warships commanded by Vice Admiral Kamimura Hikonojō in the Tsushima Strait between Korea and Japan, which resulted in the Battle off Ulsan. The Japanese force had four modern armored cruisers, Iwate, Izumo, Tokiwa, and Azuma. Early in the engagement, Rurik (the rear ship of the Russian formation) was hit by Japanese fire three times in the stern, flooding her steering compartment so that she had to be steered with her engines. Her speed was decreased, splitting it from the rest of the Russian ships, further exposing her to Japanese fire, and her steering jammed to port. The Russian Admiral Karl Jessen attempted to provide cover for the ship, but was pushed back by the Japanese cruisers. As the Russian ships withdrew, Rurik was set upon by several Japanese cruisers. Rather than surrender the ship to the Japanese, the senior surviving officer, one Lieutenant Ivanov, ordered the ship to be scuttled. The Japanese picked up about 625 survivors, the rest perishing in the engagement.

The remaining two Russian cruisers escaped back to Vladivostok.

Legacy[edit]

Despite her obsolete physical appearance, with the barque rigging and unprotected guns, Rurik performed surprisingly well at Ulsan. The ship was quite possibly responsible for the escape of the other two Russian cruisers, though that can also be attributed to the Japanese indecisiveness at the battle.[2] While Rurik's presence was decisive at Ulsan, the Russians subsequently wasted the second chance they had at using Rossia and Gromoboi. Rossia joined Bogatyr with grounding damage and Gromoboi never sortied for the rest of the war.

References[edit]

Bibliography[edit]

- Brook, Peter (2000). "Armoured Cruiser vs. Armoured Cruiser: Ulsan 14 August 1904". In Preston, Antony (ed.). Warship 2000–2001. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-791-0.

- Budzbon, Przemysław (1985). "Russia". In Gray, Randal (ed.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1906–1921. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. pp. 291–325. ISBN 0-85177-245-5.

- Campbell, N. J. M. (1979). "Russia". In Chesneau, Roger & Kolesnik, Eugene M. (eds.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1860–1905. New York: Mayflower Books. pp. 170–217. ISBN 0-8317-0302-4.

- Frampton, Victor; Head, Michael; McLaughlin, Stephen & Spurgeon, H. L. (2003). "Russian Warships off Tokyo Bay". Warship International. XL (2): 119–125. ISSN 0043-0374.

- McLaughlin, Stephen (1999). "From Ruirik to Ruirik: Russia's Armoured Cruisers". In Preston, Antony (ed.). Warship 1999–2000. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-724-4.

- Warship International Staff (2015). "International Fleet Review at the Opening of the Kiel Canal, 20 June 1895". Warship International. LII (3): 255–263. ISSN 0043-0374.

- Watts, Anthony J. (1990). The Imperial Russian Navy. London: Arms and Armour. ISBN 0-85368-912-1.

External links[edit]