How Bruce Lee’s Way of the Dragon made Chuck Norris a star with their fight in Rome’s Colosseum, and what the film showed about Lee’s directing

- Bruce Lee was allowed by Golden Harvest’s Raymond Chow to direct The Way of the Dragon because Lee had clashed with veteran director Lo Wei on Fist of Fury

- The film shows Lee’s desire to inject his movies with humour and has a fight scene featuring Chuck Norris that unwittingly made the American an action film star

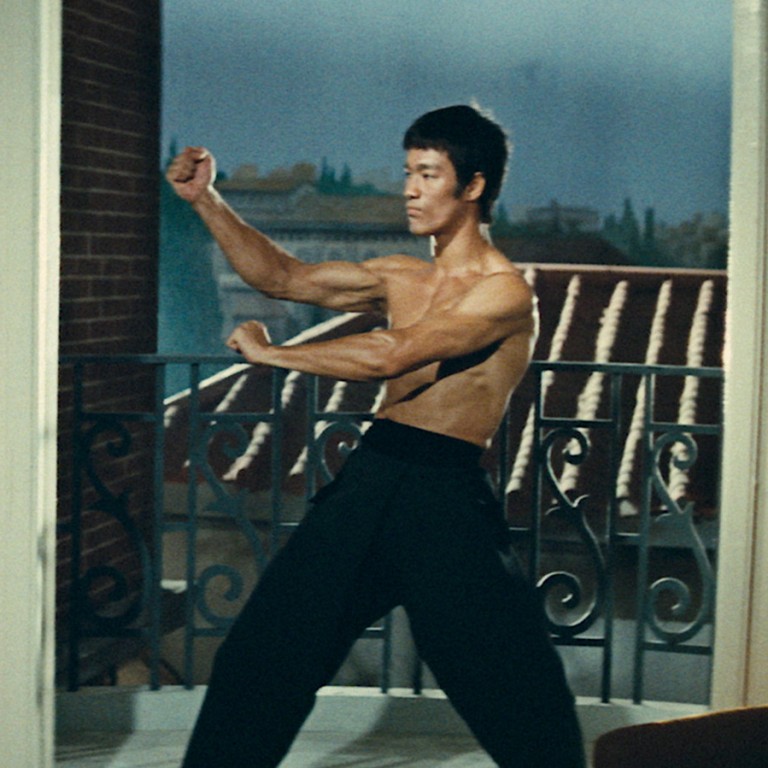

Less revered than his previous two kung fu films, Bruce Lee’s 1972 The Way of the Dragon is notable nonetheless for highlighting the martial arts star’s potential as a writer/director – as well as for a stunning finale which pits Lee against American karate champ Chuck Norris in Rome’s ancient Colosseum.

“The first work to be directed by Bruce Lee is sadly a flawed and transitional work which now must remain as Lee’s testament, a reminder of the themes he could have developed further, and with more assurance and confidence, had he lived,” writes academic Stephen Teo in Hong Kong Cinema: the Extra Dimensions.

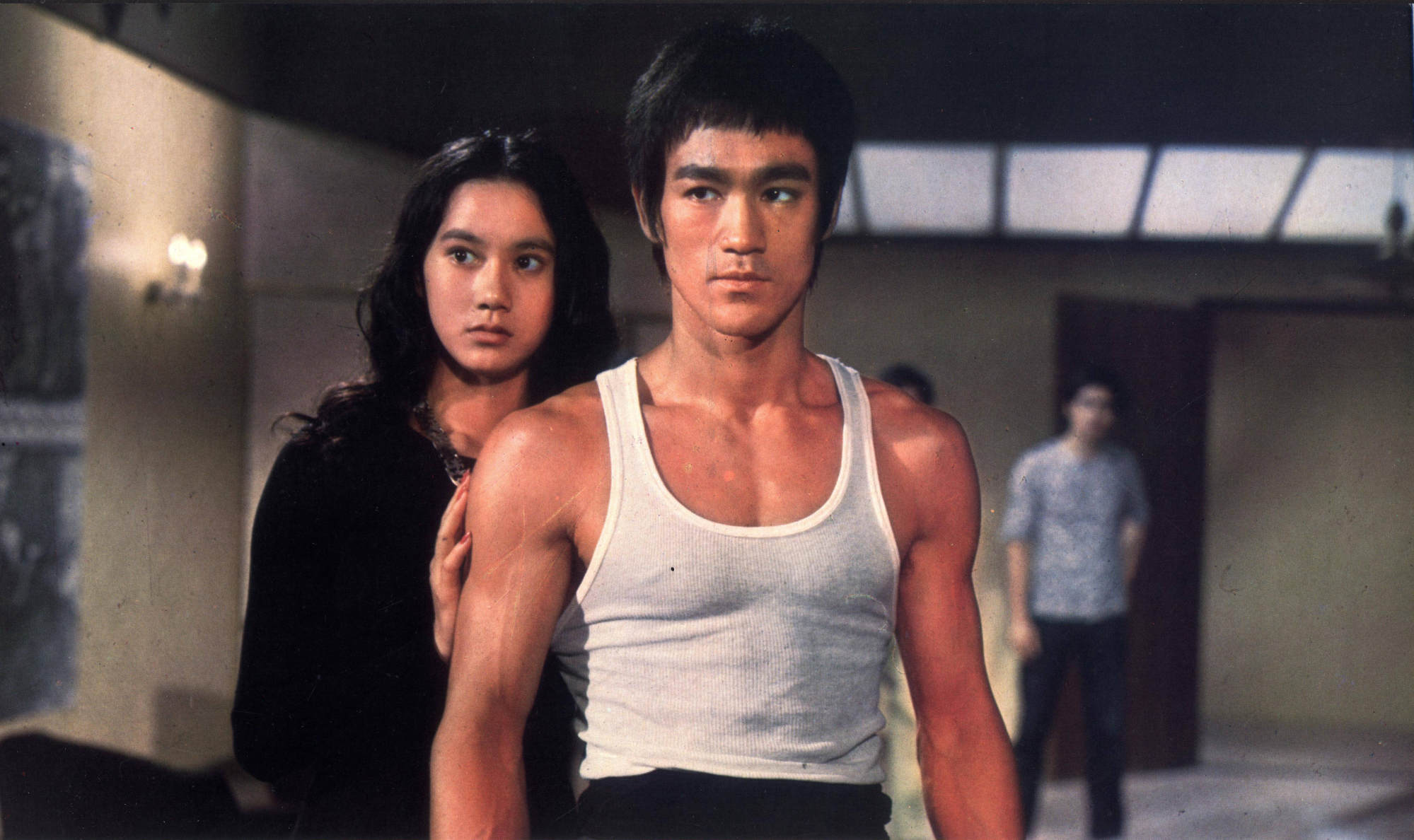

The story features Lee as the bumpkin-like Ah Lung, who travels from Hong Kong’s rural New Territories to Rome to dispense with a criminal gang who are trying to take over a Chinese restaurant.

Lung’s unsophisticated manners initially see him dismissed as ignorant by his Chinese colleagues in the Italian city, but his martial arts skills, and his personal loyalty, soon ensure that he’s elevated to hero status among his peers.

Lee saw a chance to direct when his three-film contract with studio Golden Harvest, which had produced his first two hits, was coming up for renewal, says Carl Fox, author of the KFM Bruce Lee Society. It helped that rival studio Shaw Brothers was trying to sign the star.

Hong Kong’s first art-house film, The Arch was ahead of its time

Lee was slated to appear in Yellow Faced Tiger, a film again directed by Lo, but the star leveraged his new-found fame to get himself into the director’s chair.

“Lee’s professional relationship with director Lo Wei had broken down after Fist of Fury, and Chow knew that if he was forced to work with the veteran director for a third time, Lee would have walked away from Golden Harvest after his three-picture deal. He would have gone to Shaw Brothers, who were already offering him vast sums of money to jump ship.

“Knowing he could not match Shaw’s offers, Chow sought a new solution to keep Lee on the books, and he suggested that Lee and Harvest form a joint production company which would give Lee the opportunity to write, direct, produce and star in his movies,” Fox says. Lee formed Concord Production with Harvest, and The Way of the Dragon was the result.

Lee quickly realised that he didn’t have the budget for a period piece, and shifted the setting to the present day.

Lee’s casting of Norris was an inspired decision

The idea of shooting in Rome was inspired by Clint Eastwood’s success with Italian spaghetti westerns such as A Fistful of Dollars, according to Lee biographer Matthew Polly.

Eastwood was initially a TV actor in the US – he was a popular star of the Western series Rawhide – but had started his film career working for Italian director Sergio Leone. His success in the spaghetti westerns kickstarted his career in Hollywood.

Lee, who still wanted to make movies in the US, thought that a film set in Rome might do the same for him.

Rome’s Colosseum – areas of which were recreated in Golden Harvest’s studios in Hong Kong – is the backdrop for the film’s piėce de resistance, a bout between Chuck Norris and Lee. Norris and Lee had become friends when they met at the US karate championships in 1968, and Lee invited him to Hong Kong to appear in The Way of The Dragon.

Norris, who had no desire to become a movie star, accepted the gig because he thought that the film might prove to be good publicity for his martial arts schools. But the film unexpectedly made Norris a major action star in his own right.

“Lee’s casting of Norris was an inspired decision,” says Fox. “Lee originally wanted Joe Lewis, another dominant American karate champion, for the role, but after reading the script and realising his character is beaten by Lee, Lewis declined – he wasn’t going to let it be implied that Lee could beat him, even if it was just in a fictional movie. When he bowed out, Norris stepped in.”

“It’s true that Lee’s agenda was to imply that he could beat Lewis and Norris, but Lewis may have regretted the decision in later life, as it catapulted Norris’ career into the stratosphere, and he became one of the biggest action heroes of the 1970s and 1980s. If Lewis had agreed to the role, perhaps we’d all now be asking, ‘Chuck who?’”

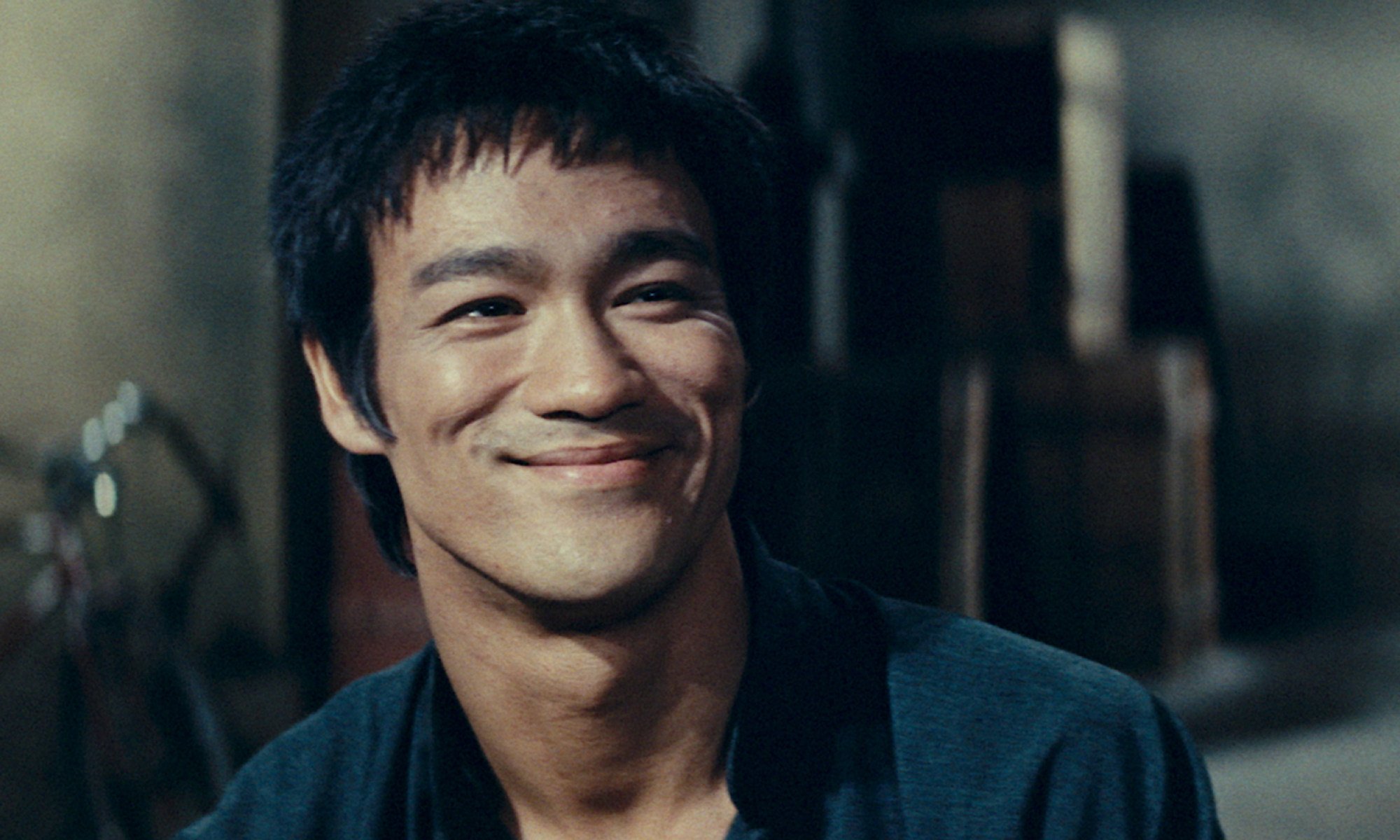

One of the interesting facets of The Way of the Dragon is the way that Lee experiments with comedy, even making his character the butt of crude jokes.

“Lee had already introduced a bit of humour in Fist of Fury, in the scene he dressed up as a telephone repairman. He expands on that in The Way of the Dragon. Right from the get go, Lee was making the audience laugh,” Fox says.

Although his attempt at a comedic character falls short because of caricature, it’s something that Lee could have taken further. “Alas, Lee died before he could develop this persona further in more representative works,” Teo writes.

Although it was a hit in Hong Kong, Lee thought that The Way of the Dragon fell short, and he decided it was not good enough to further his career in Hollywood. He tried to stop Raymond Chow releasing the film in the US, but Chow sold the rights anyway – and it was a big hitthere upon its full release in 1974.

In this regular feature series on the best of Hong Kong cinema, we examine the legacy of classic films, re-evaluate the careers of its greatest stars, and revisit some of the lesser-known aspects of the beloved industry.