Robert Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool

Tory Party

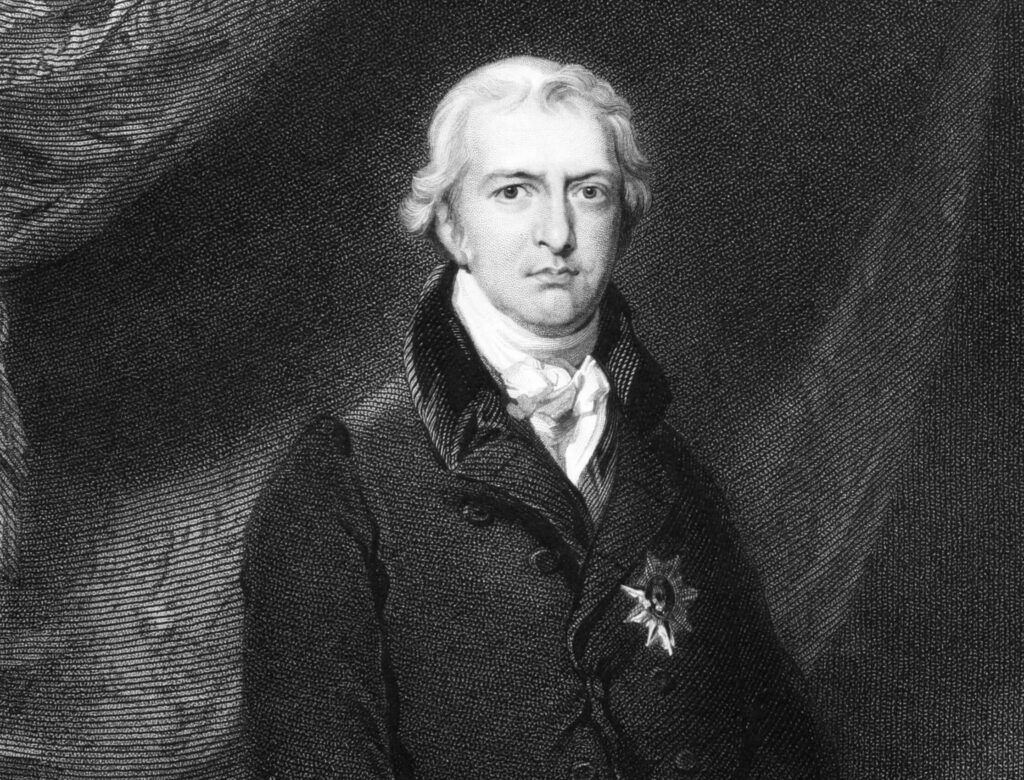

Image credit: Robert Banks Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool, Sir George Hayter, 1823. © National Portrait Gallery, London licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Robert Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool

…to risk perpetual strength for the peculiar triumph of one year? A government…were bound to recollect that their cases were not momentary but everlasting; not of partial but entire; and that they had to provide for the future as well as the present…

Tory Party

June 1812 - August 1827

8 Jun 1812 - 9 Aug 1827

Image credit: Robert Banks Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool, Sir George Hayter, 1823. © National Portrait Gallery, London licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Key Facts

Tenure dates

8 Jun 1812 - 9 Aug 1827

Length of tenure

14 years, 305 days

Party

Tory Party

Spouses

Louisa Hervey

Mary Chester

Born

7 Jun 1770

Birth place

London, England

Died

4 Dec 1828 (aged 58 years)

Resting place

Hawkesbury Parish Church, Gloucestershire, England

About The Earl of Liverpool

Little remembered today, Lord Liverpool was the most significant of Pitt’s heirs and he maintained the Pittite system until the second half of the 1820s. His premiership saw the final defeat of Napoleon and a new order established across Europe, guided by his Foreign Secretary Lord Castlereagh. He was an effective manager of ministers, and, rather like Walpole, maintained the political scene, to which he became indispensable. With his departure, the old order soon came under unbearable strain and reform became inevitable. Lord Liverpool was the third longest serving Prime Minister in history, and the most recent of the top three to have been in power.

Lord Liverpool was born Robert Jenkinson in London into a landowning family in 1770. He was educated at Charterhouse and Christ Church, Oxford. While at Oxford, he did the customary ‘Grand Tour’ of Europe, happening to witness the Fall of the Bastille on 14 July 1789.

In 1790, Jenkinson was elected to the seat of Rye, which he held until 1803. In Parliament, he quickly caught the attention of Pitt the Younger and other leaders, delivering several strong speeches. He would be a Colonel in a defence unit during the 1790s (though retained his seat in the Commons). In 1793, Pitt put Jenkinson on the Board of Control for India and promoted him to Master of the Mint in 1799. From 1796-1803, Jenkinson was known as Lord Hawkesbury (a courtesy title and he remained in the Commons).

In 1801, upon Pitt’s resignation, the new Prime Minister, Addington, made Hawkesbury Foreign Secretary. His first task was to negotiate the peace of Amiens that ended the French Revolutionary Wars. The coalition powers had tired of fighting, and the French Revolutionary armies had not only held them back but had counterattacked and won new territories. The peace was signed in 1802 but collapsed in 1803 and fighting began again.

In 1803, upon the death of his father, Hawkesbury became Lord Liverpool and he was elevated to the House of Lords.

In 1804, Pitt returned to Number 10, and Liverpool served as Home Secretary. When Pitt died, the King sent for Liverpool and asked him to form a government, but Liverpool refused, believing that he lacked the majority. Liverpool then spent a year in opposition, before returning as Home Secretary in Portland’s cabinet in 1807. In 1809, when Perceval became Prime Minister, Liverpool was appointed Secretary of War. Liverpool worked hard to secure loans and run the British war effort, despite a bleak outlook, with Napoleon largely triumphant in Europe.

Perceval was assassinated on 11 May 1812. The Prince Regent asked four men to be Prime Minister before Liverpool accepted office nearly a month after Perceval’s murder. Aged almost exactly 42 years old, Liverpool was younger than all of his successors.

Liverpool’s priority was war, for Britain was fighting two wars within weeks of the beginning of his premiership. First, there was the epochal conflict with France. In June 1812, Napoleon made a terrible mistake, invading Russia, only to see his army destroyed on the retreat from Moscow. Britain could now count on Russia as an ally. That summer, Wellington defeated the French at Salamanca, and the tide began to turn in Spain. A Sixth Coalition with the European powers was negotiated in 1813. By early 1814, this coalition, together with a large British army under Wellington, had defeated the French, and Napoleon was dispatched into exile on the Mediterranean island of Elba.

The second war was with the United States of America. It had been provoked by the British impressment of American sailors into the Royal Navy. Repeated American invasions of British Canada were defeated by the British, while British raids along the US coast achieved some success, before ultimately failing at Baltimore and New Orleans. In 1815, the Treaty of Ghent was signed, with the two sides agreeing to effectively revert to status quo ante bellum.

A new settlement for Europe was now negotiated, Foreign Secretary Lord Castlereagh was dispatched to Vienna, where he played a key role in the peace conference. In March 1815, Napoleon escaped, and another coalition was formed to defeat him. Soon afterwards, Napoleon was defeated by an Anglo-Dutch-Prussian army at Waterloo and soon was dispatched into exile on the British territory of St Helena. The Congress of Vienna was finalised, creating a new European order, and one that left Britain a powerful country.

With peace came fiscal retrenchment, the downsizing of the armed forces, and the abolition of the wartime income tax. The government tried to fight the latter, but Liverpool’s political position was always quite tenuous, and he never had a majority in the Commons. Consequently, when the vote came, the government was defeated. In contrast, Liverpool’s government reluctantly authored the Corn Laws, to protect the harvests of the landed classes, which would cause great problems for his successors.

Discontent was rising due to economic depression and the misery of 1816’s ‘Year Without a Summer’, which had caused crop failures. There were Luddite protests in the countryside and clamour for political reform from the cities. In 1817, Liverpool suspended habeas corpus in Britian, extending the measure to Ireland in 1822. In August 1819, a large protest in favour of reform was attacked by local Yeomanry in Manchester, killing 18. The repressive Six Acts were adopted by the government to suppress agitation. In 1820, the Cato Street Conspiracy plotted the massacre of Liverpool and the entire government but was foiled by London’s first professional police force, the Bow Street Runners.

Another crisis came in 1822, when King George IV determined on divorcing Queen Caroline. Reluctantly, and knowing that this would cast a revealing light on George’s long history of personal licentiousness, Liverpool introduced a Bill to Parliament. The proceedings were a sensation, with the Queen watching from the galleries as the Lords debated the Bill. Ultimately, it passed the Lords, but was withdrawn before it reached the Commons.

By the mid-1820s, the government’s finances were in a much healthier condition, and the country was showing signs of good economic health once again. Though Liverpool was devastated by the death of Castlereagh in August 1822, he asked Canning to take over as Foreign Secretary.

One of Liverpool’s great strengths was that he was an effective manager, keeping the forceful personalities that sat in the Cabinet Room largely harmonious. Five past and present Prime Ministers were in Lord Liverpool’s cabinet: Addington (as Lord Sidmouth), Goderich, Canning, Wellington, and Peel (whilst Lord Palmerston was non-Cabinet Secretary of War). Though the fissures in the Pittite/Tory ranks were becoming more pronounced as the years passed, especially between the liberals and the reactionaries, things would only break apart when Liverpool departed the scene. Liverpool knew that his Cabinet was loyal to him, and they would resign with him if he asked them, allowing him a good deal of latitude with the Prince Regent (George IV).

Despite his reputation as a reactionary, Liverpool was not anti-reform. By the end, he was seen as one of the more liberal members of the Cabinet, and he was supportive of free trade, which would become a Victorian economic doctrine. But, by and large, Liverpool made incremental changes on reform, for example he was prepared to consider Catholic voting, but not full emancipation. Even when he considered reform inevitable, his government would not be the one to do it, and it repeatedly blocked reform proposals throughout the 1820s.

Liverpool was the first president of the Royal National Institution for the Preservation of Life from Shipwreck, which in time became the RNLI. He also helped to fund the National Gallery.

Liverpool married Louisa Hervey in 1795. She died in 1821. He remarried to Mary Chester in 1822. They had no children.

In April 1827, Liverpool suffered a stroke, and decided to retire. He died in December 1828.

Collections & Content

Andrew Bonar Law

Bonar Law was the shortest serving Prime Minister of the 20th Century, being in office for just 209 days. He was gravely ill when he t...

The Earl of Rosebery

Lord Rosebery was Gladstone’s successor and the most recent Prime Minister whose entire parliamentary career...

Arthur James Balfour

Arthur Balfour was Salisbury’s successor. He had a reputation as a good parliamentarian, a capable minister, and an excellent ta...

The Duke of Wellington

Wellington is a Prime Minister who is today largely remembered for achievements unrelated to his premiership. ...

The Duke of Grafton

The Duke of Grafton believed, according to Horace Walpole, that ‘the world should be postponed to a whore and a...

Benjamin Disraeli

Charming, brilliant, witty, visionary, colourful, and unconventional, Benjamin Disraeli (nicknamed ‘Dizzy’) was one of the greate...

Boris Johnson

Boris Johnson is one of the most charismatic and controversial politicians of the modern era. To supporters, he was an authentic voice wh...

The Earl Grey

Earl Grey was the great aristocratic reformer. His government passed the ‘Great Reform Act of 1832’, ending an entire e...