Baseball players weren’t regular guys, but in 1974 they earned only slightly more than three times what the average American family paying to watch them play brought home. That year, the same year Rickey Henderson turned 16, the median household income in the United States was $11,000. The average major league salary was $35,000. Hank Aaron was in the final year of a three-year, $600,000 contract that at signing had made him the highest-paid player in the history of the game at $200,000 per season. A year earlier, Willie Mays retired. Mays ended his spectacular 22-year career never making more than $180,000 a year. There were always the outliers – a few players who dwarfed what the average American worker brought home, like Babe Ruth, who earned $80,000 a year during the Great Depression years of 1930 and 1931.

The outliers were the Mount Olympus guys, however, guys like Aaron and Mays, DiMaggio and Williams, who were the best to ever play baseball – and who made their biggest money near or at the very end of their career.

Even though the players were the game, they didn’t share in the profits. The public was rarely sympathetic, however, because most fans would kill to be able to just once – just once! – hit a ball the way Reggie did at Tiger Stadium when he took Dock Ellis off the transformer at the 1971 All-Star Game, or to hear the crowd gasp for them the way it did for Rickey when his fingers waggled, his legs gave that predator’s twitch … and … bam! – he was gone.

The players got the fame, the girls, the cheers, and the whole world chanted their names. To the average Joe, the anonymous cog working in his miserable cubicle every day who literally had to beg just to get a lousy 25-buck-a-week raise, adulation was compensation enough. To the public, no matter what the salary, the players were always the lucky ones. It would enrage Marvin Miller, the executive director of the Major League Baseball Players Association, every time this position was reinforced when the multimillion-dollar business of baseball was referred to as a kid’s game, and worse, every time the players themselves sank into that sugary, love-of-the-game bullcrap and told the world they loved baseball so much they would have played for free.

By opening day 1984, Rickey was 25 and the average American household income had increased two and a half times, to $26,430 … but the average big league salary? It was now 12 times higher, at $329,000. The players had fought and won their freedom from the reserve clause that had bound them to one team for life, and with free agency – the dreaded free agency that even the players were brainwashed into believing would kill the game if realized – came the real money. It was the real money of a free market – the self-made, you’re-worth-whatever-someone’s-willing-to-pay-you kind of market that was now theirs. It was the kind of capitalism by which Americans always said they swore, and they did swear by it – until they saw just what these suits were willing to pay professional athletes (to play a kid’s game!).

When he worked for the Major League Baseball Players Association under Miller, Dick Moss feared the changing perception of the athlete, and he was right: as the money grew, so too did the resentment. Moss feared that the more the players earned, the less human they would become to the public. As they earned more money, players were expected by fans to be perfect, and even the coaches and peers who should have known better – they had played or coached in the game and knew firsthand just how difficult it actually was – developed the same expectation. At that kind of money, guys should be hitting .600 every season, even though that wasn’t how any of it worked. Whether a player’s annual salary was $100,000 (ridiculous!), $1m (to play baseball?) or $40m (never ever gonna happen!), the basic arithmetic of the game was unchanging: the very best players in the game were going to get a hit 30% of the time, and the very best teams, whether their payroll was $10m, $50m, or $350m, were going to win between 95 and 105 games. Teams had been playing baseball since the 1870s, and only six teams in history had ever won 110 or more games in a season.

It was the nature of the sport, and no amount of free-agent money or pennant-buying owners could ever change that arithmetic. It had always been about the money, but never so much as during Rickey’s time. Salaries had broken the sound barrier of comprehension. (He makes how much?) The public was still bitter toward players after the 1981 strike, and instead of embracing the rising value of their teams, the owners plotted revenge. The public said it did not care who was at fault – yet always found a way to blame the players, remaining both angry and incredulous about each new record-breaking contract. It wasn’t who was making the money. It was the money itself. “The fans were fascinated by money. They loved the celebrity,” former A’s president Roy Eisenhardt recalled. “But now Casey doesn’t just strike out. There’s no joy in Mudville. It’s ‘You struck out – and you’re a fucking asshole.’”

The rise in salaries was so sharp and so public. In the real world, the woman down the hall may have suspected how much more her male coworkers earned, but in sports everybody knew. Near the end of spring training, the Associated Press, The Sporting News, and later USA Today would print out the team payrolls and the individual salaries of every player. This information fascinated and enraged the fans, who now felt the unfairness of the capitalism they so deeply embraced, especially as they saw their own wages decline, failing to keep up, or worse, when their unions couldn’t protect them and the layoffs were announced. The public also wanted the players to compare their salaries not to each other’s, but to what fans made. The A’s offered Rickey $950,000 for the 1984 season. Rickey wanted $1.2m. From his first contract five years earlier, Rickey’s salary had risen more than 5,300%. At $1.2m, the percentage increase from when he entered the league would have been more than 6,700%.

From the very beginning of his baseball arc, when Tommie Wilkerson had to bribe him with a quarter for every base he stole just to get him to step onto the field, the percentage increase he was earning from playing baseball was 480%. In later years, when the public was confounded by squabbles over astronomical dollar figures, the player response would turn into a cliché. It’s not about the money, they would say, and the fans would roll their eyes and vow never to watch baseball again – just before getting sucked into another pennant race.

Rickey was different. Arbitration was about respect. Every year he’d been in the big leagues, he felt he’d had to fight for his money, even when the numbers proved he had done exactly what was asked of him – and more. He had to fight just to reach the big leagues, when the A’s wouldn’t promote him directly out of spring training in 1979. Respect came through money. Money told him what the A’s front office believed about him, but it also reflected where he stood with his peers – and to him what the A’s thought of him demeaned his game. The public often scoffed when an athlete would declare that their issue wasn’t the money, and certainly while Rickey understood better than anyone that he was now making 54 times what he earned as a rookie just five years earlier, he wasn’t comparing his salary to what he once made but to the going rate for star players.

Whether he was a rookie or a legend, it was money that fueled him. Years later, in 1989 after he had finally become a champion, it was time to cash in. Rickey had become a free agent a week after the World Series and was going to be the coveted player at the winter meetings – if testing the market was his objective. As the baseball world prepared to descend on the sprawling Opryland Hotel in Nashville, the word was that the Dodgers, having failed at it for coming up on two decades, were going to make another run at Rickey. Rickey wanted to stay in Oakland. “He wants more than one year,” the team’s general manager, Sandy Alderson, told the writers, “and he wants a sizable raise, which is not surprising.”

On 22 November 1989, outfielder Kirby Puckett became the first player in baseball history to average a $3m annual salary when he signed a three-year, $10m deal with the Twins. Six days later, on 28 November, Richie Bry and Alderson agreed on a whopper of a deal for Rickey: four years and $12m – the highest contract in the game. After being doubted in New York, dominating the postseason, he had finally done it: Four years, $12m. Guaranteed. A no-trade clause. The highest-paid guy in the game. That was ace-of-the-staff money. That was cleanup-hitter money. A leadoff hitter was leading the market. Nobody had done that before.

It might as well have lasted 30 seconds. Rickey was the game’s highest player literally for 48 hours. Two days after his deal, the Angels signed a pitcher, the left-hander Mark Langston, to a five-year, $16m contract. In the span of nine days, baseball had broken its record contract three times. After Langston’s deal, Dave Stewart wanted a contract extension – that was about respect too. During the first weeks of January, Eric Davis signed a three-year, $9.3m deal with the Reds – topping Rickey’s annual salary. That same week, the A’s gave Stewart a two-year extension at $3.5m per year – topping Rickey. A week later, the Giants gave Will Clark, their National League playoff MVP, a four-year, $15m extension – topping Rickey. A month after the final pitch of the season was thrown, Rickey was the highest-paid player in the game. A month before the first pitch of spring training, he was the third-highest-paid player in his area code. Rickey was enraged.

“Don’t ever underestimate one thing with Rickey – it’s always about the money. Always. Always,” Stewart recalled. “I wasn’t playing for money. I played to make sure people knew I played the game. I wanted my fucking name known, that if you were going to let those other pitchers’ names roll off your tongue, don’t forget mine.”

Mike Norris, Rickey’s former roommate in Jersey City in the minor leagues and a 20-game winner in the big leagues himself, always took an easier, more philosophical view of arbitration, and of the money in general. The structure of sitting across from one’s employer may have felt adversarial, and indeed it was: the team was arguing against paying a player what he believed he was worth – a player who after the hearing was now expected to put on the uniform and bust his ass for the home team that had just argued he wasn’t worth what he was asking. Norris, however, saw the silver lining of the situation: Rickey was not fighting a pay cut – teams could hit a player with up to a 25% slash – and in fact the A’s were offering a $150,000 raise. Rickey was asking for an even bigger one.

“Arbitration never bothered me,” Norris said. “Hey, no hard feelings. The way I saw it, I was either going to wake up rich – or richer.”

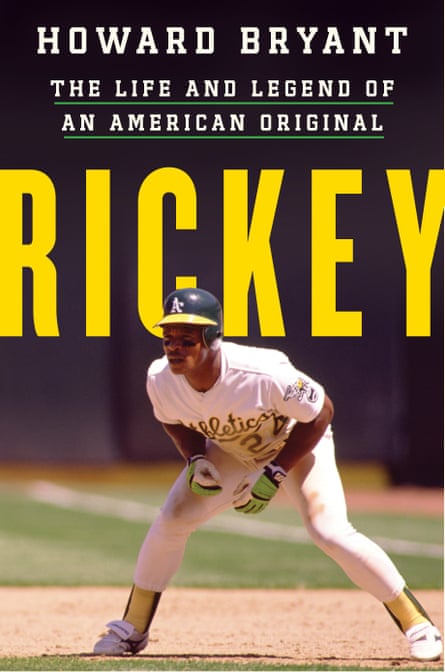

Adapted from the book Rickey: The Life and Legend of an American Original by Howard Bryant. Copyright © 2022 by Howard Bryant. From Mariner Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Reprinted by permission.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion