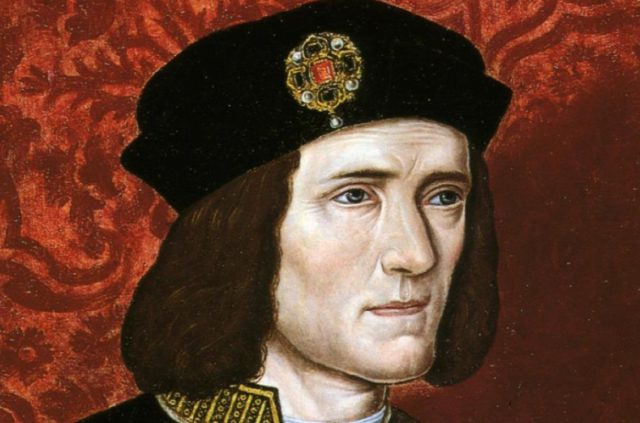

England's King Richard III is at the center of one of the most famous assassination legends in history, immortalized in one of William Shakespeare's greatest tragedies. It's quite the tale: a power-hungry duke seizes the throne when his brother unexpectedly dies, and he orders his young nephews (one the rightful heir) murdered in the Tower of London to cement his claim to the throne. But was he really a murderer? The debate over Richard III's presumed guilt has continued for centuries. Now, a British historian has compiled additional evidence of that guilt, described in a recent paper published in the journal History.

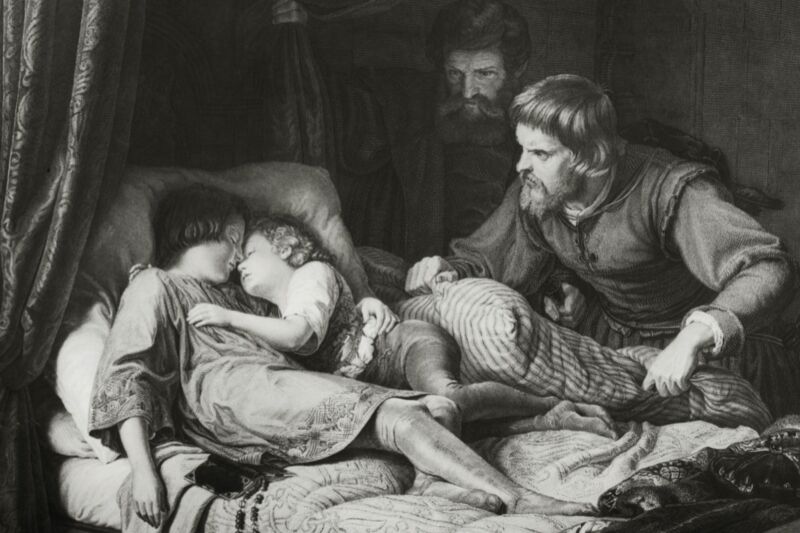

The so-called "princes in the Tower" were the sons (aged 12 and 9) of King Edward IV, who died unexpectedly in April 1483. Edward's elder son and heir (now technically King Edward V) and the younger sibling (Richard of Shrewsbury, Duke of York) were originally brought to the Tower of London in May by their uncle, Richard, Duke of Gloucester, ostensibly to prepare for Edward's formal coronation. But the coronation was postponed until June 25 before being postponed indefinitely. Gloucester assumed the throne instead as King Richard III, and he had Parliament officially declare young Edward and his brother illegitimate the following year.

Although no bodies were produced at the time, historians largely agree that the princes were likely murdered in late summer of 1483. Two small human skeletons were found at the Tower of London in 1674, but there is no conclusive evidence that these were the princes, despite a perfunctory examination in 1933 concluding that the remains were those of children roughly the same ages. Two more bodies that may have been the princes were found in 1789 at Saint George's Chapel, Windsor Castle. Forensic scientists have been unable to gain royal permission to conduct DNA and other forensic analysis on either set of remains in order to make a proper identification.

Rumors began circulating almost immediately that the princes had been murdered by order of Richard III. Even today, Richard remains the most likely culprit, based on various accounts written in the ensuing years, including the only contemporary account (penned by an Italian friar named Dominic Mancini); the Croyland Chronicle; an account by French politician Philippe de Commines; Thomas More's The History of King Richard III; and Holinshed's Chronicles—the latter written in the late 16th century, and one of Shakespeare's primary sources for his play.

However, Richard III was never formally accused of the murders. His successor, Henry VII (House of Tudor), made only general accusations of "unnatural, mischievous and great perjuries, treasons, homicides, and murders, in shedding of infant's blood, with many other wrongs, odious offenses and abominations against God and man." Other possible culprits include Henry Stafford, 2nd Duke of Buckingham and Richard III's right-hand man, or Henry VII, supposedly to strengthen his claim to the throne. The case for Richard III's innocence was even memorably popularized in mystery writer Josephine Tey's classic 1951 novel The Daughter of Time, which claims that the rumors were the result of highly effective Tudor propaganda. (It's a great read, but it hardly qualifies as a scholarly argument.)

But it's Thomas More's account that provides this latest evidence in favor of Richard III having ordered the princes killed, according to Tim Thornton, a historian at the University of Huddersfield. More specifically identifies the culprit as James Tyrell, an English knight who fought for the House of York and confessed under torture to the murders on the king's orders. Before he was executed, Tyrell also implicated two accomplices. More alleges that these two men were Miles Forest and John Dighton. Many of Richard III's defenders have dismissed More's account as mere Tudor propaganda, given More's clear Tudor loyalties; his account was also written many years after the disappearance of the princes.

Thornton begs to differ with that assessment, arguing in his new paper that More based his account on information gleaned from sources who, in More's words, "much knew and had little cause to lye." Through painstaking research, Thornton has identified two of More's fellow courtiers between 1513 and 1519 as the sons of Forest—Edward and Miles—and he believes they are the sources that More refers to in his history. There is even mention of one of them in More's correspondence to Cardinal Thomas Wolsey. This strengthens the credibility of More's account and the case for Richard III's guilt.

Ars sat down with Thornton to learn more.

Ars Technica: What drew you to investigate this particular historical mystery?

Tim Thornton: I recognized that most people try to address this problem by trying to understand the disappearance of the princes by working back from its ending. For them, in a way, the story ends in July 1483. For me, that was when the story begins. So I decided to work my way forward, trying to look with fresh eyes at the accounts that began to be built up of the events of 1483. In More's case, I was trying to view his account as a great work of literature and of political thought and also as an attempt to create a narrative and a way of understanding a period of political crisis.

I think we haven't really fully understood the degree to which people in the early 16th century lacked a coherent narrative of that period in which, as so often [happens] in the aftermath of civil conflicts and civil war, generations were coming to terms with that legacy. It does often take many years to build a narrative. When I cast a fresh eye over More's account, I discovered that he was living and working with two men who were identifiable as the sons of a man he then identified as the chief murderer of the princes. So we're actually dealing with direct connections between the people that he lived with and the people who were at the very heart of the coup, and of the killing, that took place in 1483.

Ars Technica: Several historians cite the "Tudor propaganda machine" as evidence for Richard III's possible evidence. What's your response to that aspect of the argument?

Tim Thornton: This is one of the fascinating areas of recent exploration in our understanding of Henry VII's reign in particular. I think there's been a rather glib solution that Henry came to the throne and launched a full-blown detailed propaganda effort to destroy Richard's reputation, and to do so on the basis of a minutely detailed account of what had happened in the period up to August 1485, when the Battle of Bosworth Field took place. That's the complete opposite of what took place. Henry avoided, quite deliberately, any presentation of the specifics of what occurred before he seized the throne. One of the reasons for that is because he inherited a political nation that had lived through extraordinary political turmoil, as king had succeeded king, regime had succeeded regime.

That was the wise thing to do in Henry's position. To attack in detail the previous regime would have meant attacking many of the people who were now increasingly prominent in his own regime. What he did was attack in a very abstract form the evils of the past, which were identified with a rather abstract personification of Richard. That was a very cunning approach.

But there was no detailed attempt to explain what had happened to the princes. There was a rather echoing silence that sounded across the land as to what might have happened to them. Richard was associated with the killing, but the detailed account that might have come forth about what had happened to them was singularly lacking. After 1485 in particular, I think in the popular mind, there is no question that people believed Richard was responsible in a rather general way for the death of the princes.

Ars Technica: One of the things that makes More's account so compelling is that he includes many specific details, fashioning a convincing narrative out of his research. But he was a Tudor loyalist, and that bias is always an issue when assessing the various historical accounts.

Tim Thornton: There's no question. This is a man who was a protegé of [Archbishop of Canterbury] John Morton. He is in awe of John Morton, when you read his descriptions of Morton in Utopia. Therefore you have to recognize the degree to which he's influenced by some of the architects of what we would now call the Tudor regime.

I guess I would just set against that the fact that there is evidence for the responsibility of [Tyrell accomplices] Miles Forest and John Dighton for the death of the princes. There is ample corroborating evidence to suggest that, for example, Miles Forest was responsible for their custody in the tower. There is ample corroborating evidence to suggest that Miles Forest came from Barnard Castle, off in County Durham, where he was previously a servant of Richard, as Duke of Gloucester, prior to his seizure of the throne. It would be very hard to imagine that this was a piece of imagination that was constructed in order to blacken the reputation of Richard from a Tudor loyalist's perspective.

Ars Technica: Can you elaborate a little on the evidence for your identification of the sons of Miles Forest as the More's sources with "little reason to lye"?

Tim Thornton: We know that there was a real Miles Forest who was potentially the chief murderer. We also know that he was dead by September 1484 and that he left a widow, Joan, and a son, Edward. It was then a matter of identifying Edward Forest, who appears as a servant of Henry VIII, and linking him as being plausibly the Edward who is that son of Miles Forest. Edward had a brother who was called Miles. Both of them have that strong connection back to Barnard Castle and to other lordships in the North of England, principally Midland, which is so known for its links to Richard himself.

What struck me was the degree to which there were connections between those two men and More himself. Those connections are quite remarkable in the way that they coincide with the period when More was conceiving the ideas in the History of Richard III. There was a [July 5, 1519] letter More wrote to Wolsey that was my eureka moment. I looked at the letter and saw More's signature at the bottom and a reference to Miles Forest as the messenger between that embassy and the court. So More would have been talking to Miles Forest, and we now can be pretty confident that Miles Forest is the son of the man who was guarding the princes in the tower—and that Miles Forest is the man More says is the source for this story.

Ars Technica: Your research helps solidify the accepted narrative over the years, that the princes were murdered by the order of Richard III. So where do you go from here?

Tim Thornton: I've only explored some of the evidence for the construction of these narratives in this paper. There is further to go. When you start to think about the way these narratives were created, the survivors of 1483, and the way that they are present in subsequent decades—the opportunities for the historian are really very exciting. That's the world that I'm exploring now.

DOI: History, 2021. 10.1111/1468-229X.13100 (About DOIs).

reader comments

158