After the execution of King Charles I in 1649, the nation embarked upon a new form of governance, a republic under the watchful eye of Oliver Cromwell. This Commonwealth experiment was to last only until 1660, when, under Oliver Cromwell’s son, Richard, the republic crumbled and the monarchy restored.

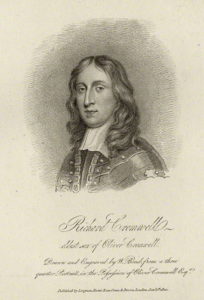

Richard Cromwell proved to be nothing like his father, so much so that within eight months of inheriting his mantle, he ended up resigning from his role of Lord Protector. The fate of the country was settled by the new parliament which immediately voted in favour of the monarchy.

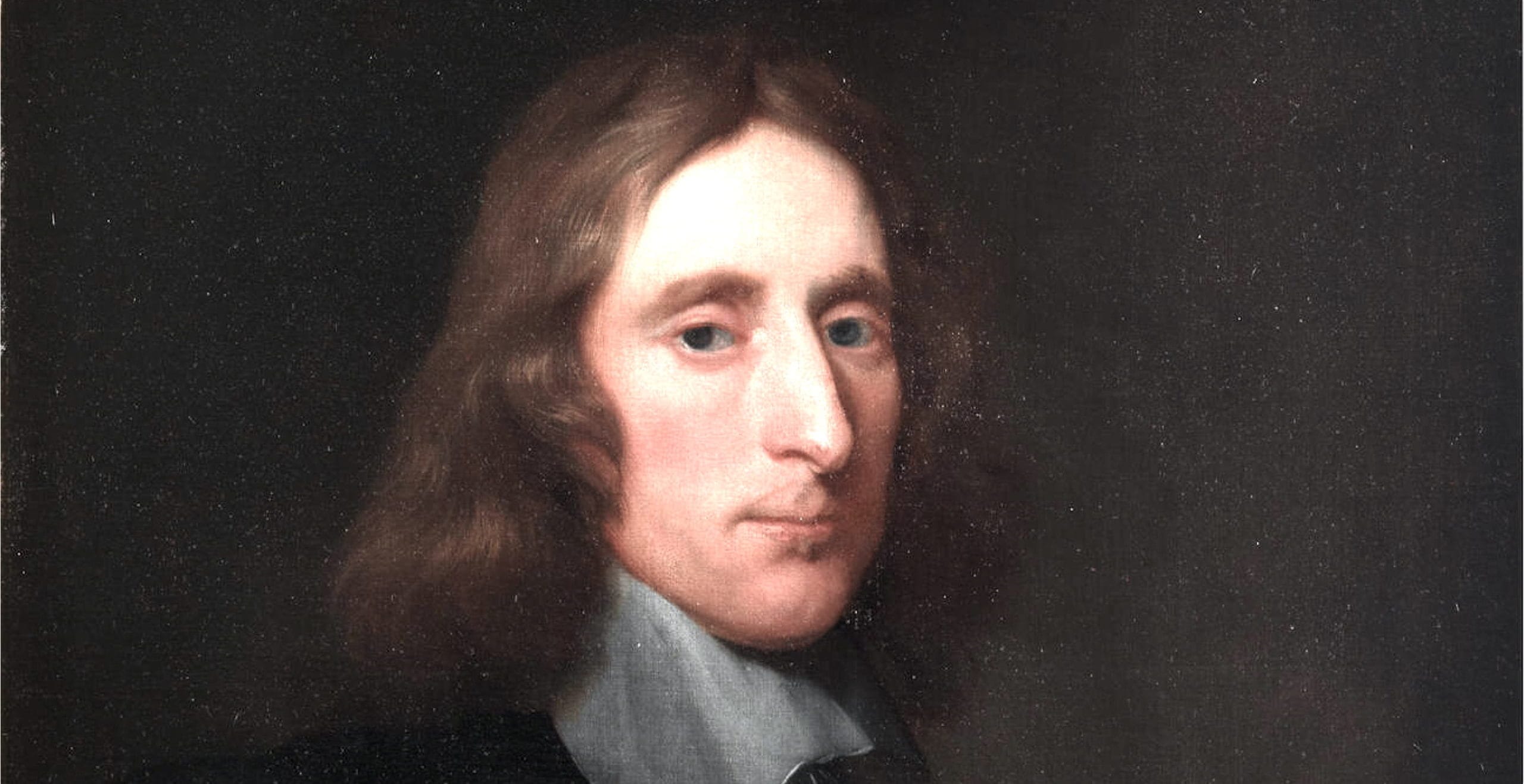

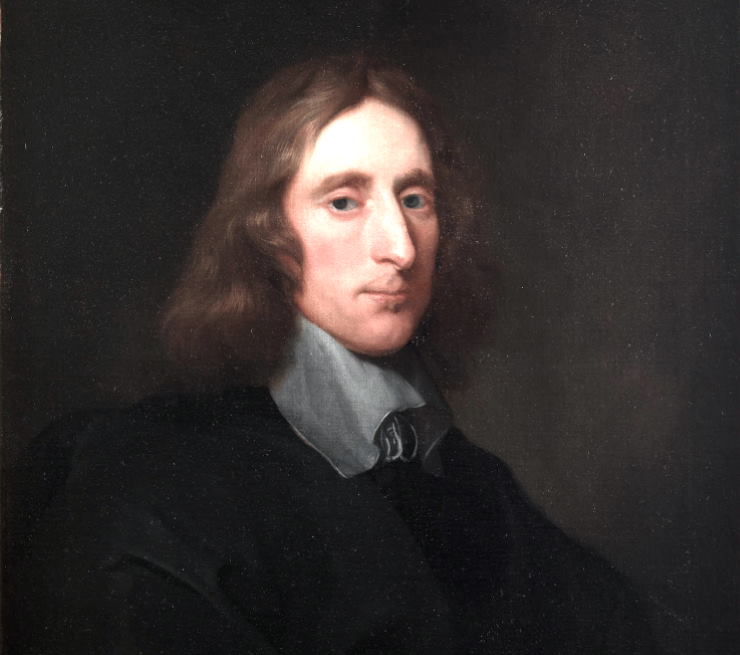

The attempt at establishing a republic was the brainchild of Oliver Cromwell who had become de facto monarch in everything but name.

Living in the shadow of his father, Richard grew up in a large family, the third son and with eight other siblings. Born in October 1626, very little is known about his childhood apart from his education at Felstead School in Essex.

He then went on to become a member of Lincoln’s Inn and by 1649 he had entered into a successful marriage with Dorothy Maijor, whose family were part of the gentry. The married couple went on to live in the Maijor family estate in Hampshire and had nine children.

Meanwhile, Richard served on various committees and fulfil a number of roles including as a Member of Parliament. Despite his father doing his best to prepare him for more responsibility, a correspondence with Richard’s father-in-law illustrates Oliver Cromwell’s concern for son’s apparent lack of ambition and drive. With no interest in studying and an inclination for idleness and a love of luxury, Richard Cromwell from the start did not share many attributes with his father. Despite this, Oliver Cromwell would continue to prepare him for the takeover of his position when he passed away.

This would include Richard serving as Chancellor of the University of Oxford, as well as being a member of the Council of State, courtesy of his father.

In the meantime, Cromwell’s vision for the nation was struggling to find a way forward: devising a workable political settlement for the Commonwealth proved harder than Oliver Cromwell could have imagined.

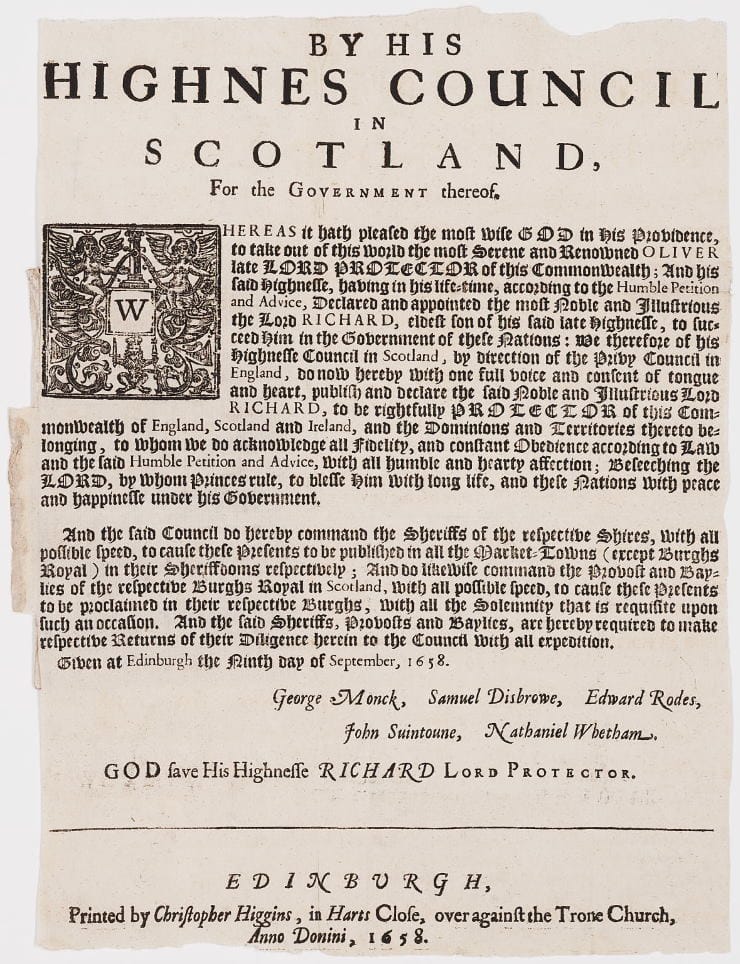

By 1657 the Humble Petition and Advice had been adopted as constitution, put forward and presented by the former Lord Mayor and MP Sir Christopher Packe. The resulting arrangement arose as a reaction to the “New Cromwellians” who were more supportive of the traditional monarchical form of governance, in contrast to the initial militaristic nature of the early Protectorate.

Cromwell strongly disagreed: despite serving in the capacity as “Your Highness” and being housed in Whitehall Palace, he had strong religious motivations and an unshakeable belief that the overthrow of the monarchy was God’s will.

Cromwell thus refused the Crown in May 1657 and the clause of kingship was removed. He knew that any revelations of personal ambition at the expense of the republic would have serious ramifications.

By 25th May 1657, with ailing health and an updated version of the Humble Petition and Advice now implemented, his nomination of his son as Lord Protector only underlined his role as de facto king and leader.

Despite his best efforts to see his vision realised, Cromwell passed away on 3rd September 1658, leaving an inheritance of a crumbling and unstable British Republic.

Richard was immediately informed of his father’s wishes for him to succeed him as Lord Protector. Nevertheless, there still remained some speculation and controversy surrounding his appointment, with some intimating that he had put forward his son-in-law instead. A letter from the time recognised Cromwell’s oral declaration of his son as successor and so, without further ado, Richard was hastily declared Lord Protector, the second person to serve in such a role.

After taking up the appointment, it became abundantly clear that he was very different from his father and such a role was beyond his capabilities.

One of several problems he faced was the army and in particular the lack of authority he could command, given his lack of experience. His father had climbed the greasy pole of politics and become commander of the New Model Army in the context of the English Civil War. For those who had fought to secure a military victory, Richard’s lack of credentials were viewed with suspicion.

Richard simply inherited such responsibilities through an act of nepotism which would prove fatal in attempting to stabilise such a precarious political situation.

With an inability to gain the necessary respect level from the New Model Army Richard would be unable to prevent the infighting that would result from senior figures.

He also managed to alienate any support from military figures when he refused their advice about hiring someone with more experience to be Commander in Chief.

Moreover, tensions were made worse when the army began to question the government’s commitment and the direction they were taking the country in.

The resulting action taken by the army was to state their grievances via a petition taken to parliament in April 1659.

Whilst going through the formal channels to express their complaints, parliament simply put the army’s protestations to one side and continued to pass laws that were seen as prohibitive to the processes of the military and in some cases specifically targeted them.

None more so than the case which was brought against William Boteler who had been a major-general under Oliver Cromwell and who was subsequently accused of mistreating a prisoner on the Royalist’s side of the civil war. His impeachment naturally enraged those that had fought to see the Republic created.

Only days later, two further legal indications of a clamp down on the military was instigated when a law was passed prohibiting meetings of army officers without Richard Cromwell and the parliament giving permission.

The final straw came with the inclusion of an oath forcing officers to swear that they would not undermine parliament.

With the battle lines clearly drawn between politicians and the military, the time to act was now. With the army taking action against Cromwell, power was seized and parliament was dissolved by Richard on 21st April 1659 under the watchful eye of the officers. Following Richard’s initial refusal to dissolve parliament, troops gathered at St James’s Palace, forcing Cromwell to comply.

In a series of events which precipitated not only Richard’s personal downfall but the very state of the British Republic, the military officers now recalled the Rump Parliament on 7th May 1659.

In a matter of only a month, after refusing assistance from the French Richard Cromwell was dismissed by the Rump Parliament and forced to deliver his formal resignation from the role of Lord Protector.

His overthrow also dealt with the rather pressing issue of mounting debts which had grown considerably during his time in charge. As part of the agreement, his resignation secured the payment of his debts and also a pension, allowing him to escape to Paris in 1660 and eventually settle in Geneva.

Meanwhile back at home, the British Republic which had been built by his father was falling apart. With Richard, a sense of direction had been lacking; his father had commanded authority where Richard’s attempts were met in equal measure with derision and suspicion.

With the constitutional experiment in republicanism failing, chaos loomed on the horizon. Thankfully, a parliamentary army man by the name of George Monck helped to avoid such a crisis after he marched his men to London and restored the Long Parliament. This would then dissolve and set the stage for new elections whereby a “Convention” Parliament sought the sensible and stable choice of restoring the monarchy.

With anarchy narrowly avoided, on 23rd April 1661 Charles II was crowned at Westminster Abbey, bringing the English chapter of revolution and republic to a close.

Richard lived the rest of his life out in relative obscurity, ending his final days in England.

The Cromwellian experiment was complete; monarchy now reigned supreme and the trials and tribulations of royal authority would continue…

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Published: 2nd December 2020