France Invaded Germany Between WWI and WWII

A treaty enforcement action

The end of World War I was a joyous occasion for nearly everyone. The war had exacted a terrible cost in lives and infrastructure around the world and the peace prompted a global sigh of relief. Germany, however, soon learned that peace was not enough for the victorious powers, they wanted vengeance and loot.

As part of the Treaty of Versailles, Germany was ordered to pay reparations to the Allies for the damage the war caused. Most of the money was to be given to France who bore the brunt of the awful fighting inside its borders. Reparations or war loot are not uncommon following a large conflict but the bottom line number that was handed to Germany was simply outrageous.

The amount owed was nearly a trillion dollars (adjusted for 2022 values) that was to be paid over the course of many years. The number was simply too large to be feasible.

Germany also had weathered the war and was in no position to make good on the payments. Unsurprisingly, they defaulted.

Renegotiating the terms of the agreement

After the default, the signatories agreed to restructure Germany’s war debt. They halved the amount owed down to, a still large, 500 billion dollars and agreed to accept payment in the form of raw resources and industrial output. If France could not get the cold hard cash they were promised, they would settle for steel, coal and other important goods.

This was also a serious burden to Germany whose economy was still in shambles. Now, they had to turn over what little money they had as well as a portion of their industry. It was untenable.

Factories closed. Workers were laid off. Fuel prices skyrocketed. Germany defaulted, again. The economy teetered.

All of this came to a head in 1922 as Germany struggled to turn over any perceptible amount of what they owed. It was not as though Germany was doing well for itself, the world could see how bad the German Republic was suffering. The economy was in awful shape, unemployment was high, the German currency was nearly worthless. Suddenly, the treaty meant to repay the Allies for their damages was beginning to look cruel.

But France was not to be denied.

Occupation of the Ruhr

The French Prime Minister at the time, Raymond Poincaré, did not want to see Germany wriggle out of its obligations due to international sympathy. Instead of agreeing to a moratorium on debt payment, as the British suggested, Poincaré decided to take drastic measures to secure what he felt that France was owed.

He invaded.

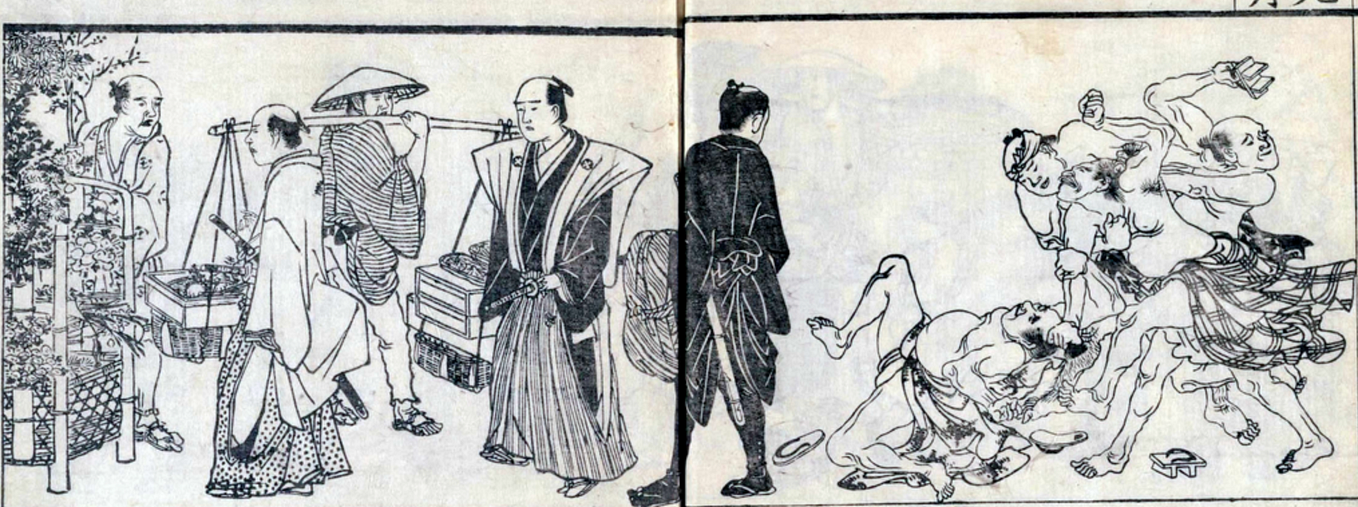

In January of 1923 the French 32nd Infantry Division marched across the eastern border into Germany. Their mission was to occupy the industrial Ruhr Valley and take, by force, the resources that Germany had agreed to turn over to France.

Soon, French troops were marching through the impoverished streets of the German Republic. The Ruhr was one of the only regions of Germany that was still productive and the occupation removed what little life the German economy had left in it.

Sympathy for Germany grows

France was expecting more support from its allies for their actions in Germany but they quickly found themselves acting alone. Belgium was the lone nation that supported France’s invasion of the Ruhr region. Britain strongly disagreed with France’s methods and did not think that invading Germany was the right response.

Around the world, sympathy for Germany began to grow. It now looked like France was picking on their rival out of spite rather than any sort of legitimate reason. Even though Germany owed the money via the legally binding treaty, many people began to see the Treaty of Versailles as a method of punishment and torture rather than a peace document.

France’s actions in the Rhineland would have grave consequences that extended far beyond 1923.

Aftermath and impact

France’s occupation of the Ruhr would last nearly three years. They invaded in January of 1923 and did not withdraw until August of 1925. The invasion was a spectacular failure at almost every level.

France did not get any more money out of Germany. Instead, a new plan was put in place to reduce the burden that Germany was shouldering. They would end up getting less in the long run, not more.

The invasion and occupation of a critical German territory only bolstered support for Germany internationally which is what led to the gradual lessening of the treaty obligations over time.

Internally, the French occupation of the Rhineland became a rallying cry for far right extremists and it lit the fires of nationalism in the bellies of Germans everywhere. This slight only hastened the rise of people like Adolf Hitler and gave Germans every excuse to support his eventual invasion of France.

Raymond Poincaré was ousted immediately following his invasion plan. His coalition lost their majority in 1924 and his government was replaced by an entirely different party (though he would be reelected in 1926 after the withdrawal).

This is a largely forgotten piece of Interwar history but it was, in many ways, a catalyst that quickened the rise of the Nazi Party and World War II. Without the sympathy that the invasion garnered, Germany might not have had the restrictions on their economy loosened. The concessions and draw down of debt helped Germany get back on its feet much quicker than previously expected which allowed them to reforge a war machine in just fifteen years.

That might have been seriously delayed if France had not marched over the border in 1923.

Join Medium to support me and thousands of writers like me.

Click here to subscribe.