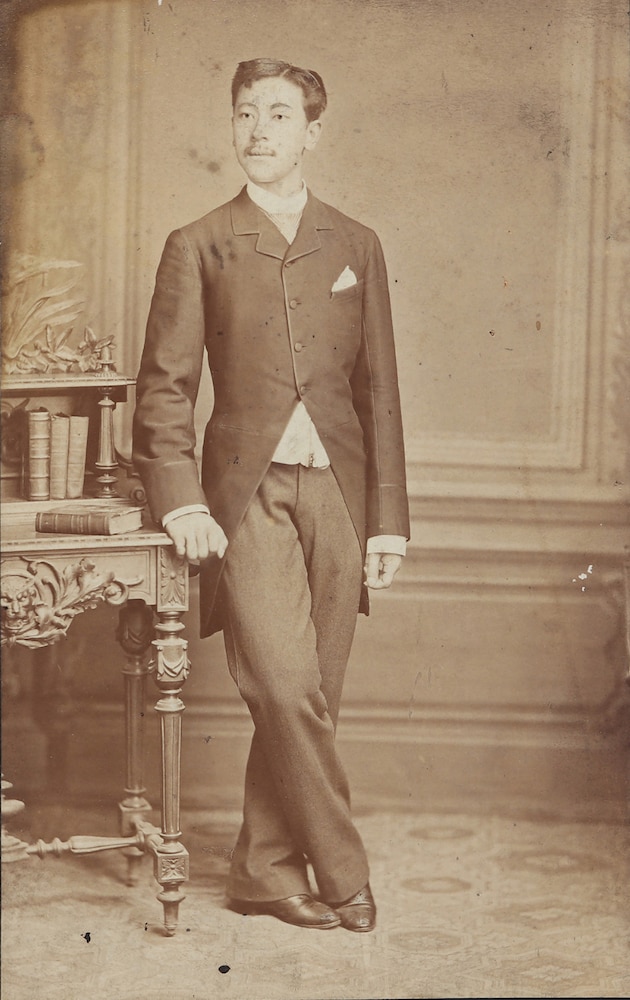

At a time when oppression by our Spanish colonialists was the prevalent condition in these islands, a young, brilliant Filipino pondered the situation and asked himself the hard questions about racial superiority, education, and privilege. Realizing he had the same qualities and resources as the colonizers, if not more, he resolved to beat them at their own game. He possessed the audacity to declare he was indeed equal, in words and deeds and style, if not superior, to the ruling Spaniards. That Filipino is none other than Pedro Alejandro Paterno.

True, he had an unfavorable reputation for decades. But he was really more of an intensely patriotic intellectual and visceral aesthete than the self-serving politician some believed him to be. If one delves more into his silent, honorable accomplishments and achievements rather than the man’s flamboyant actuations, one will see a Renaissance man worth the national recognition and historical reconsideration.

Rare and exquisite pieces from his storied life are at the center of a special Leon Gallery auction happening this August 20. Called The Illustrado Trove, it features treasures exhibited from the great Exposicions in Spain, among them a portrait by Felix Resurreccion Hidalgo, a bust by Mariano Benlluire, historical rare books, and other ethnographic and cultural wonders.

Born to great wealth in 1857, a time when most Filipinos practically had nothing but dried leaves and grass to protect them from the elements (nipa, buri, anahaw buli, etc), and when even most Spanish expatriates lived in modest rented rooms and houses, the young Pedro grew up a prince in a local version of a European palace located in the elegant “arrabal” (district) of Santa Cruz, Manila.

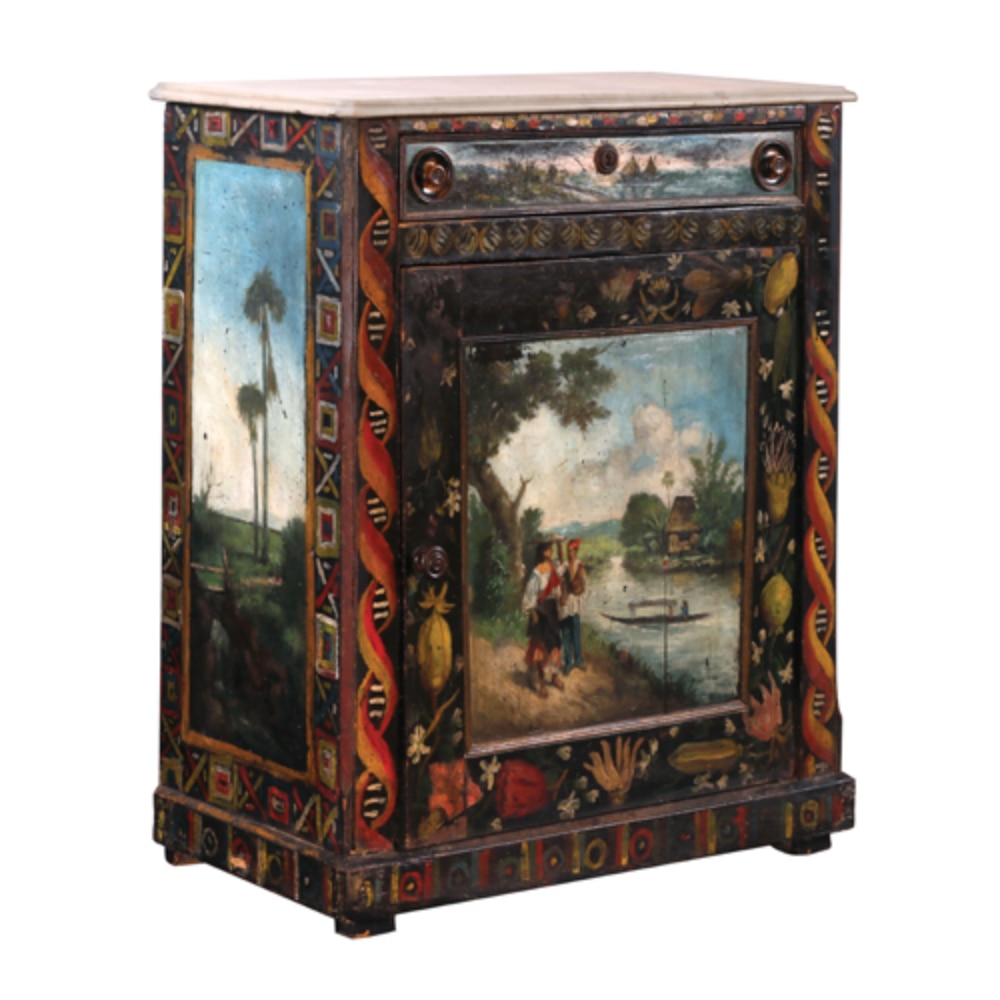

His home was almost unreal in its opulence, with an enfilade of French–style salons decorated with crystal chandeliers, tall gilded mirrors, paintings, marbletop tables, elegant chairs, and English and Eastern rugs. There was a large “despacho” office library in the home’s entresuelo/mezzanine level.

Living it up in Madrid

Once in Madrid as a 14 year–old, and unlike other Filipino students who lived in downscale dormitories in modest neighborhoods (among them Jose Rizal), Pedro thought it fit to rent an entire wing of the Palacio of the Duque de Salamanca in the city’s most exclusive section. Fellow Filipino expatriates christened his palatial

crib in half–jest as “La Casa de Molo”—which was truth because the source of the high rental payments was the ambitious Capitan Maximino Paterno in Manila, who, wishing to maintain if not further his family’s august social rank, fully supported his son Pedro’s Madrid adventure in the grandest possible manner.

Felix Roxas y Fernandez, an engineering student from one of the DBF clans, described Paterno’s life in Madrid as “quite simply, above the throng” with all the trappings of aristocracy: a regal home, household staff, a complete aristocratic gentleman’s wardrobe, elegant soirees, important guests, a black carriage with the family crest in silver and the coachman and footmen in livery, etc.

Pedro earned his degrees in Theology and Philosophy with honors at the Universidad de Salamanca. In 1880, he became a Doctor of Civil and Canon Law at the Universidad Central de Madrid (now Universidad Complutense). His social life revolved around the Madrid aristocracy; his good friends were Spanish nobility and officials. He even married an aristocratic Spanish lady, Doña Luisa Pineyro y Merino. No Filipino expatriate in Madrid lived as luxuriously as Don Pedro Paterno, with the exception of the visiting industrialists Don Pedro Pablo Roxas and Don Gonzalo Tuason.

In 1893, Pedro became the recipient of the “Gran Cruz de la Noble y Distinguida Orden de Isabel la Catolica,” a prestigious and coveted Spanish award.

Ambassador of Filipino culture

Possessing great noblesse oblige, Paterno tirelessly promoted high Filipino culture and exquisite arts and crafts to European society—out of his personal funds—from his #16 Calle Sauco residence. He was possibly the earliest Filipino “heritage advocate” as well as a pioneering collector of Filipiniana.

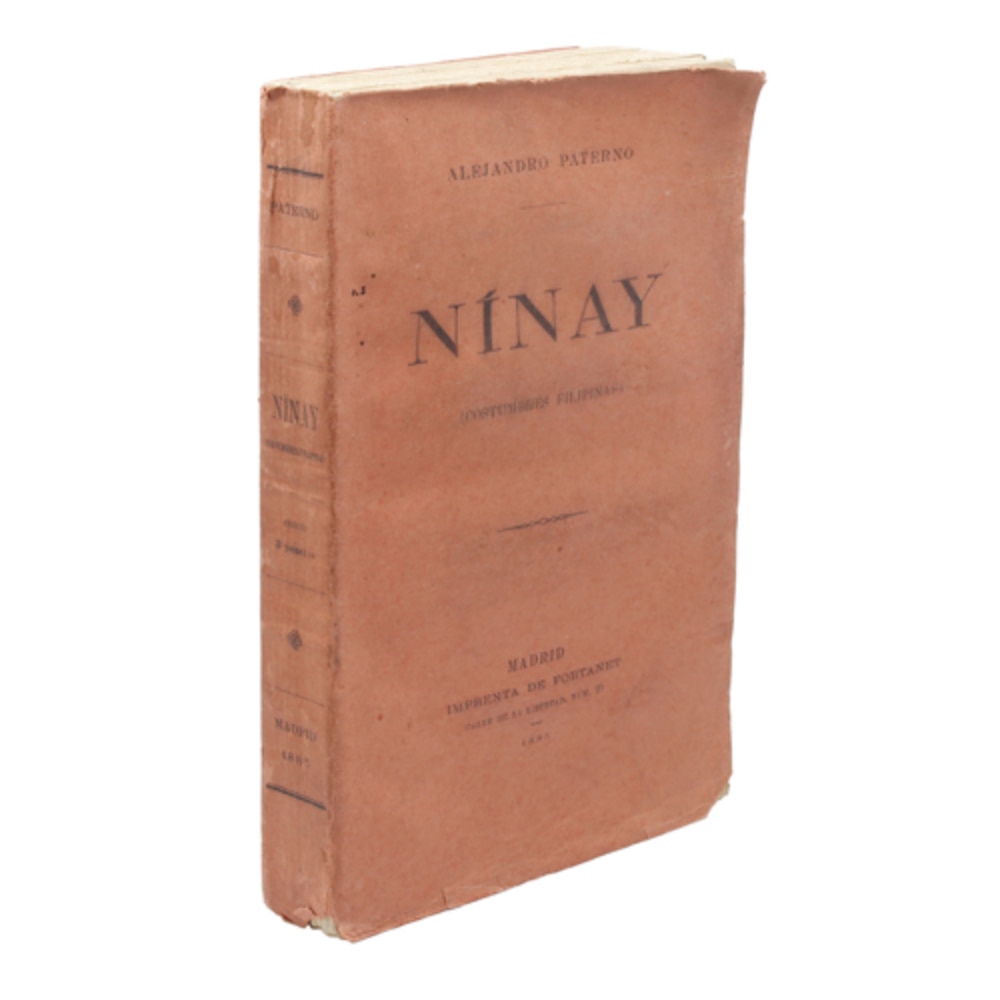

In 1880, he wrote and published “Sampaguitas y otras poesias varias,” the first collection of poems by a Filipino in Spanish, and “Poesias Liricas y Dramaticas.” In 1885, he wrote and published “Ninay,” the first novel in Filipino. “Ninay” was a roman–a–clef in the way that it drew so much from the life of the Paterno–Devera Ygnacio family. Over the course of a literary life of 31 years (1880–1911), Paterno produced 36 major works that ran the gamut from history, law, prose, poetry, etc.

Like all ilustrados, he dreamt of a reformed, improved relationship between Madre España and Las Islas Filipinas, as visualized/idealized in Juan Luna’s allegorical painting “España y Filipinas,” for which Pedro commissioned his talented compatriot.

A Duke in every way

Seeing the 1896 Revolution gradually destroy the Filipinas he loved profoundly, Paterno volunteered as mediator between the Spanish colonial authorities and the Filipino revolutionaries. This concluded in The Pact of Biak–na–Bato wherein both sides agreed to the cessation of hostilities in December 1897. Paterno became the President of the 1898–99 Malolos Congress and then the Prime Minister of the First Philippine Republic in June 1899.

He also became the Representative (Congressman) of the First District of Laguna, an eminent lawyer in Manila, and a professor at the Liceo de Manila. During the early American period, Paterno was appointed the first Director of the Museo–Biblioteca de Filipinas. An American official described him in the early 1900s thus: “A Duke in everything but title.”

Pedro Alejandro Molo Agustin Paterno y Devera Ygnacio was born on February 27, 1857 to three generations of Chinese mestizo wealth in Binondo and Santa Cruz, Manila. He was the son of Capitan Maximino Molo Agustin Paterno y Yamson (“Capitan Memo”) and his second wife Carmen Devera Ygnacio y Pineda (“Dona Carmina”). Maximino, already born to increasing Paterno prosperity in 1824, expanded his inheritance by sheer industriousness and vision. He had several big businesses in shipping, logistics, trading, and real estate.

Meanwhile, Pedro’s mother Carmen belonged to the famous Devera, Ygnacio, and Pineda families of Santa Cruz which gave the district its early prestige and luxurious reputation.

Capitan Memo married thrice and had a total of 15 children. He first married Valeria Pineda with whom he had his eldest son, Narciso Paterno y Pineda (o 1848–51). Valeria passed away young so he married her first cousin Carmen (“Carmina”) with whom he had 9 children: Agueda (“Guiday”) Dolores (“Doleng”), Jose Timoteo, Pedro, Jacoba (“Cobang”), Antonio, Maximino (“Minong”), Paz, and Trinidad (“Trining”).

Carmen also passed away young so he married her younger sister, Teodora Devera Ygnacio y Pineda (“Loleng”), with whom he had 5 more children.

Pedro’s paternal great–grandfather Ming Mong Lo was an immigrant Chinese apothecary from China with probable imperial lineage from the Ming dynasty—this is according to a Beijing scholar and genealogist. His paternal grandfather Paterno Molo de San Agustin was an extremely industrious, forward–looking, innovative businessman who excelled as a ship chandler and he set the family’s path directly to great wealth.

Pedro’s paternal grandmother Doña Miguela Yamson y de la Cruz was a direct descendant of the Rajahs of Tondo in the Old Kingdom—Suleiman II, Matanda, Lacandola—hence Pedro’s valid claim to ancient Malay royalty, the “Maguinoo ng Luzon” (according to genealogist Dr Luciano P R Santiago PhD). His paternal grandaunt Doña Maria de la Paz Molo de San Agustin married Mariano Cagalitan Assumpcion and begat a family of great artists— painters Antonio, Mariano, Ambrosio, Justiniano, and sculptor Leoncio, all surnamed Asuncion y Molo. His paternal aunt Capitana Martina Molo Agustin Paterno y Yamson de Zamora (“Capitana Tinang”) was a prosperous “sinamayera,” a dealer of embroidered textiles who combined her substantial inheritance with financial derring–do to create a real estate empire all her own.

His father’s great wealth from shipping, trading, and real estate afforded Pedro the best classical education in Manila and Madrid. The active involvement of his mother’s family—the Deveras, Ygnacios, and Pinedas—in the flourishing jewelry trade of Santa Cruz also brought substantial wealth to the Maximino Paternos. It was serendipitous for Pedro to live during the peaks of the various Paterno fortunes.

The Paternos’ affluent lives were not without difficulties, vicissitudes, and tragedies. Apart from the early passings of Capitan Maximino’s first wife Valeria and his second wife Carmen, Carmen’s talented daughters Dolores and Paz, and third wife Teodora’s infant daughter Rosenda also passed away early in life. There was also the exile of Capitan Maximino along with other “reformistas” to the Marianas islands following the Cavite Mutiny of 1872. Properties and possessions were confiscated by the Spanish authorities and the best lawyers in Madrid were hired for their retrieval.

The Paterno women perforce held the family together during various crises. The family members, despite their high social positions and identification with the highest ranks of Spanish colonial society, endangered their privileges and luxuries and gave their full albeit quiet support to the 2nd part of the 1896 Revolution and to the 1898–99 Malolos Congress, going so far as to rent a house in that town, withstand the inconveniences of provincial living, and stay there for the duration of the ceremonies.

Don Pedro passed away from complications of cholera on April 26, 1911. The American occupation beginning in 1899 imposed new challenges on the Paterno family as their large fortunes and aristocratic Spanish way of life from the 1800s were summarily subjected to the turbulent changes of the 20th century.

For more information, visit the auction site in this link.

Photos courtesy of Leon Gallery