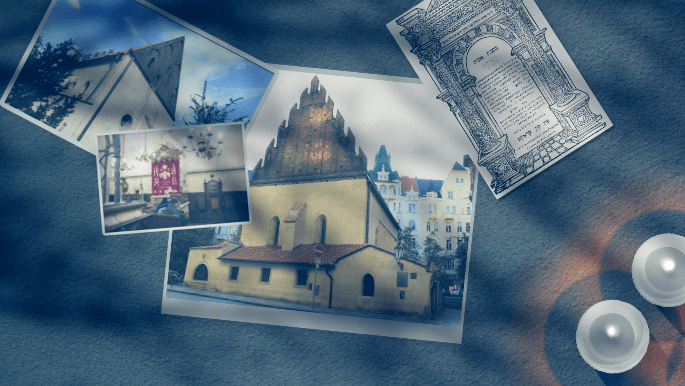

The Altneuschul in Prague is one of the oldest functioning shuls in the world. What do we know about this historical place of worship?

1. Its Paradoxical Name

The Yiddish term alt-neu means “old–new.” Why the odd name? Although not common today, this nickname was quite common in Europe. One need look no further than Nikolsburg (Mikulov), a mere three-hour drive from Prague, for a synagogue with the same name. What does it mean?

When the Jews of a town realized that their shul was too small and it was time to build a second one, the original shul became known as the “Old Shul” while the new shul was called the “New Shul.”

What happened when a third shul was built?

The Old Shul stayed the Old Shul, and the third shul became the New Shul. The second shul, the older new shul, automatically became known as the Old-New Shul.

Indeed the Altnueschul wasn’t the oldest shul in town, as Prague had its own “Alte shul,” which, as its name implies, was much older than the Altneuschul. In 1867 it was torn down, however, and the Spanish Synagogue (which currently functions as a museum) was built in its place, rendering the Altneuschul the actual “alte shul.”

What was the third shul, which gave the Altneuschul its name? It is most likely the Pinchas Shul or perhaps the Meisel Shul (the Pinchas Shul was a private family shul, and originally in a private home). Even though it was neither the oldest nor the most modern synagogue, the Altneuschul was and remains the most prominent synagogue in the city.1

2. Its Age

From its gothic architecture, one may assume that the building was erected in the 13th century, making it more than 750 years old.

3. Its Structure

Although the building may look like it was built all at once, that is not the case. The western room, now designated as the women’s section, was built first, in the 13th century. In the 14th century, the main sanctuary was built. A century thereafter, the right hallway was added. This is where the current entrance is. Only in the 18th century was the left wing (which is currently closed to visitors) built.

4. Its Hallowed Walls

Although the interior walls today are simply painted, they weren’t always. For many years no one dared to touch the walls with any tools. Some did try to give the walls a fresh coat of paint, but sadly, one after another they mysteriously died. After that, the walls were left untouched.2

On its southern wall, we still find that the last coat of paint the shul received was more than 400 years ago, in 1618—less than 10 years after the passing of the Maharal of Prague, the synagogue’s famed rabbi!

5. Coded Inscriptions

Above the heads of the worshippers, several “codes” are inscribed on the walls. They are actually acronyms for famous Hebrew phrases.

On the mizrach (eastern) wall we find: שייל״ת, דלמא"ע, which represents the phrases שִׁ׳וִּיתִי י״י לְ׳נֶגְדִּי תָ׳מִיד (I place G‑d before me, always)3 and דַּ׳ע לִ׳פְנֵי מִ׳י אַ׳תָּה ע׳וֹמֵד (Know before Whom you stand).4

On the western wall: גה"א ימ"ה and סמו"ט אטלי"ס , alluding to גָּ׳דוֹל הָ׳עוֹנֶה אָ׳מֵן, י׳וֹתֵר מִ׳ן הַ׳מְבָרֵךְ (He who answers ‘amen’ is greater than the one who utters the blessing),5 ס׳וּר מֵ׳רָע וַ׳עֲשֵׂה ט׳וֹב (Turn away from evil and do good)6 and אַ׳ךְ ט׳וֹב לְ׳יִשְׂרָאֵל ס’לה (Only good for Israel,7 forever).

6. Its Candelabras

The shul has quite a few dark brass candelabras, which hang low in comparison to its very tall ceilings. When the candelabras were lit with hundreds of candles to honor Shabbat or Jewish holidays, their flames looked like swimming stars under its tall, darkened ceilings and walls.8

7. Its Attic

Today the attic is empty. It has been thoroughly cleaned out. But it once contained collections of antique items which used to belong to Prague’s rabbis, including the remains of the famous clay Golem of Prague,9 created by the Maharal.10

8. Its Flag

In the shul, one can find a huge oddly shaped flag.

Many years ago, the Jewish Community of Prague helped the king fight against an enemy. In recognition of their service, the king granted them the right to fly their own flag. Over time, it became moldy. Then in 1716, the Jews held a grand parade to honor the birth of a crown prince in the royal court. To honor the occasion a new flag was created.11

Near the bimah, a staff almost the height of the shul stands, on which hangs a replica of the 1716 flag. Its inscription reads (translated from Hebrew):

“In the year 117, which is 1357, Emperor Charles IV granted the Jewish community the right to raise its own flag. This was renewed in honor of Emperor Charles VI with the birth of his son, Archduke Leopold, in the year 1716.”

9. Its Seating Arrangement

Today, we expect that most seats in a synagogue face the front (east). This was not always the case. In the Altneuschul, the rabbi and other elders sit facing the community, with the rest of the seats arranged around the walls, and surrounding the almemor/bima structure (see next fact).

10. Its Almemor

The almemor is the enclosed platform which houses the bimah. One ascends via the left rear corner and descends from the right rear corner.

11. Its Organ

One of the most well known features of the Altneuschul was its organ. This is not the same organs that appeared in churches and some non-orthodox temples of that era. Rather, the small positive organ was part of an ensemble, used every Friday afternoon (before the onset of Shabbat) for Prague’s traditional musical Kabbalat Shabbat.

12. Psalm 92 Was Said Twice

The Altneuschul had the unique custom to say Mizmor Shir LeYom HaShabbat (Psalm 92) twice (instead of once) on Friday eve. This tradition developed from two different customs:

- At the turn of the 16th century, the custom to begin Friday night services with this Psalm spread through Ashkenaz communities.12

- Later, the Kabbalistically-inspired Kabbalat Shabbat was introduced. It concludes with this same Psalm, which was accompanied by the musical ensemble.

These two customs were fused together to create the Altneuschul’s unique practice.

The first time the Psalm was recited, it was part of the pre-Shabbat service, accompanied by music, the congregants still dressed in their weekday clothes. The musicians would then stow away their instruments, and the congregants would go home and dress in their Shabbat finery. The women would light the Shabbat candles, and the congregants would return to shul for the evening service, which started with this Psalm13 once again.

13. The Permanently Unkosher Torah Scroll

In the Aron Kodesh of the Altneuschul, there was a Torah scroll which was never kosher to be used. ThisTorah scroll was commissioned in the times of Rabbi David Oppenheimer, chief rabbi of Prague in the early 18th century. Some young men in the community were not behaving properly and decided to donate to charity in an effort to find atonement for their misconduct. In time, the money accumulated and was used to commission a new Torah scroll, which was brought in with great pomp and celebration on Shabbat Shirah, 1728.

Alas, the very first week, a mistake was found and the Torah scroll had to be returned to the Aron Kodesh with its sash on the outside, indicating that it was not fit for use. Although they fixed it, mistakes were found continuously for the next few weeks. The scroll was, strangely enough, determined to be unfixable. When Rabbi Oppenheimer discovered its history, he forwarded the case to the Vaad Arba Aratzot (Council of Four Lands), who ruled that it was to be left as is inside the Aron Kodesh, never to be used.14

14. Under Water

In 1501, less than 10 years after the Jewish expulsion from Spain, Prague faced its share of flash floods. The Altneuschul was flooded with so much water that Rosh Hashanah services couldn’t be held in the building.15

Ninety-seven years later, in the times of the Maharal, the same thing happened. This time, the neighbouring Pinchas Shul was flooded too, and they were both inaccessible for the following day.16 The Altneuschul was also affected by the 2002 European flood, in which the Vltava swept through the older parts of the city.

Join the Discussion