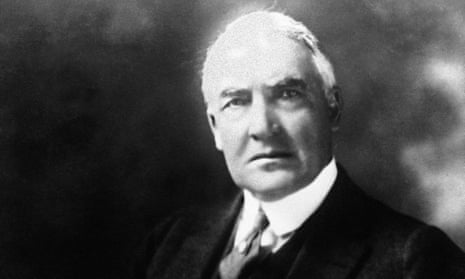

Warren G Harding, the president who ushered the US into a decade of speakeasies and big band jazz, fathered a daughter with a mistress, new genealogy tests confirm.

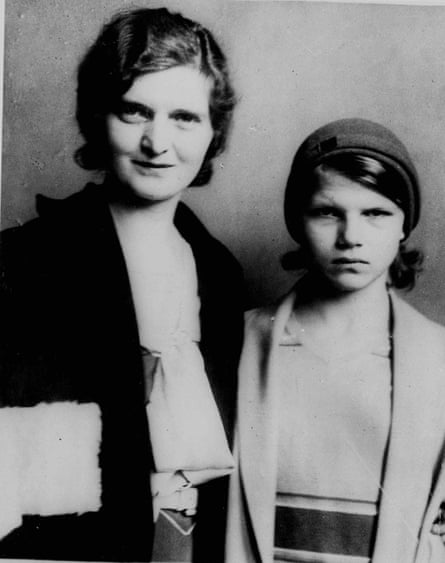

Nan Britton first claimed that Harding had fathered her daughter, Elizabeth, in 1927, a few years after the 57-year-old president died of a heart attack and left nothing for his only child. Her book, The President’s Daughter, provoked outrage and denunciations of Britton, who was accused of inventing a scandal to profit off a tainted administration.

The book was a bestseller but earned Britton the scorn of Harding relations and Americans who disbelieved the young woman without correspondence or proof.

But descendants of the Harding family – the president himself was childless in marriage – chose to solve the mystery at last this year, approaching Britton’s grandson, James Blaesing, to participate in a DNA test performed by the genealogical website Ancestry.com.

The tests found that a grandnephew and grandniece of Harding are second cousins of Blaesing, confirming that an extramarital affair had resulted in a child. The results were first reported by the New York Times.

“We’d heard about it all our lives and we’d heard it wasn’t true,” Abigail Harding told the Guardian of her cousin, Peter Harding, and the story of their granduncle’s affair. But after reading Britton’s book and other love letters by Harding, she said they became more convinced that Blaesing was their second cousin.

“We just thought we have the tools now, let’s find out the truth – is he or isn’t he?” she said. “We both felt that he was.”

After the results were confirmed, Harding said she got a call from Blaesing, who simply began: “Hi, cousin.”

The results “show 99.9% certainty”, Stephen Baloglu, an Ancestry DNA executive said. “After having tested multiple members of the Harding family, all having connections back to James, the family connection is definitive.”

Baloglu added that the company was glad to help solve the family mystery “and in this case rewriting history”.

Harding, a 72-year-old retired teacher in Ohio, said that a branch of the family remains skeptical about whether the tests are valid, and that various stories had circulated denying the president’s paternity of Blaesing’s mother.

“The one I heard was that president Harding’s father said he had mumps when he was little, and that had made him sterile,” she said. “Others just said Nan was crazy, was a gold-digger.”

In her book, Britton described how as a 17-year-old she had felt infatuated with Harding, even though he was decades her senior. She included salacious details of the affair, claiming that they conceived her daughter in Harding’s Senate office and kept the affair alive after he won the presidency in 1920.

Britton claimed that she had Harding frequently “repaired” in the White House, in “a small closet in the ante-room, evidently a place for hats and coats, but entirely empty most of the times we used it”.

She was not Harding’s only mistress. Before Britton, Harding kept up an intermittent affair with a woman named Carrie Phillips, whom the Republican National Committee is suspected to have paid thousands of dollars for her silence. Letters unsealed last year by the Library of Congress reveal that Harding did not try hard to disguise the relationship; the letters include poems, paeans to Phillips’ breasts, and anthropomorphized genitalia with the nickname “Jerry”.

The flowery, effusive language in those letters further convinced the Harding cousins that Britton’s account was true. “It sounds like a middle-school kid having his first crush,” Harding said of the president’s distinctive style. “It was really over the top.”

The DNA test should put historians finally at ease about questions on Harding’s personal life, ending the division wrought by The President’s Daughter in the 87 years since its publication.

Biographer John W Dean, who expressed skepticism in his 2001 account of the president’s life, tweeted “At last!” on learning of the new DNA test. James Robenalt, author of thebook about Harding’s administration and aims, has for years accepted Britton’s story, and urged Americans to finally move past the president’s personal indiscretions.

“It helps put this stuff all behind us I think,” Robenalt said. “You can put it down in a box and say it’s no longer a mystery and scandal that people have to wonder about. I think that it will help people to put that aside just like they do with John Kennedy and Bill Clinton and Franklin Roosevelt.”

“We’ve had a lot of presidents who’ve had personal issues in their sex lives, but there’s been a real sea change. People are more willing to say personal lives are personal. Today might be the turning point for his legacy.”

Dean, Robenalt and others have tried in the last 20 years to rehabilitate Harding’s reputation, which was for decades tarnished by corruption scandals of his advisers and his brief time in office. They note that Harding tried to address racial tensions as African Americans moved from the south to major cities; that he maneuvered through the volatile politics of anarchists, socialists and hawks in post-war America; and that he helped institute one of the first international arms treaty.

Blaesing, now confirmed as Harding’s grandson, did not immediately respond to calls for comment, but said on Thursday that the tests vindicated his grandmother. “She loved him until the day she died,” he told the New York Times. “He was everything.”

“I wanted to prove who she was and prove everyone wrong.”

Harding said that she and her cousin, who lives in California, plan to meet Blaesing next year somewhere near their second cousin’s Oregon home.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion