The event was advertised as a “pedal steel all-dayer” – something you would usually be unlikely to see outside of Nashville. But on a recent Sunday afternoon it was a pub in central London that opened its doors to eight pedal-steel guitar players.

“London, and its small independent venues, embrace the wacky and wonderful with open arms,” says Joe Harvey-Whyte, a pedal steel player who attended the annual event at the Betsey Trotwood pub. “It brings a community together in such a fractured city.”

Music is part of the streets, underground, clubs, pubs, houses, tower blocks and bedrooms of the UK capital. From the Rolling Stones to Amy Winehouse to Stormzy, and from the music schools to the venues and concert halls, the city is a centre of musical excellence and influence, says Harvey-Whyte. “Without you knowing about it, there can be hundreds or thousands of musical niches – from hurdy-gurdy players to kora players to pedal steel players.”

Does this make London one of the world’s most musical cities? If so, it is a quality that is constantly under threat by encroaching developments and rising costs. London has lost 35% of its grassroots music venues since 2007.

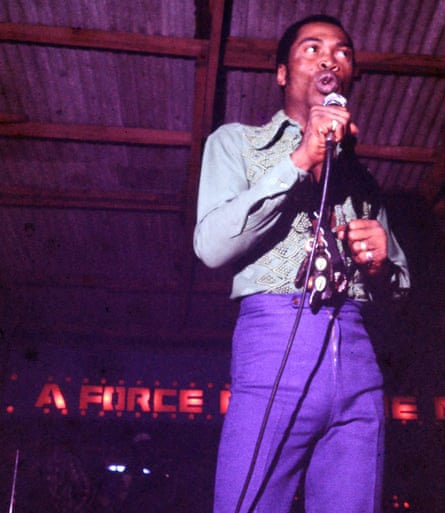

But the number of places to see live music isn’t the only way of measuring how musical a city is. Lagos, the largest city in Nigeria, has just one major venue, the New Afrika Shrine, but it represents a hugely significant part of the city’s music history: Fela Kuti, the father of Afrobeat music, performed regularly at its predecessor, the Afrika Shrine, until it burned down in the late 1970s. In 2000, on the anniversary of Kuti’s death, his son opened the New Afrika Shrine in his memory – and it is now a major tourist destination.

Or take the Red Rocks Amphitheatre in Denver, Colorado – one of the most famous venues in the world, despite the city itself being fairly small. Meanwhile, Taipei – already the centre of Mandarin pop music – is trying to establish its international musical bona fides with a new 6,000-capacity venue, complete with rehearsal rooms, studios and classrooms. The idea is to bring “more music, more musicians, more performances” to Taipei, and “elevate the whole industry”, a spokesperson from the centre said.

One major claimant to the crown is Austin, Texas, which describes itself as the live music capital of the world. There are performances every night of the week in its 200 or so venues, and it hosts festivals such as City Limits and the world-renowned South by Southwest. But Austin’s problems with gentrification highlight a huge problem for cities and their fragile music scenes.

“The number of live music venues means nothing if you don’t look at the policy that guides them and influences them,” says Shain Shapiro of Sound Diplomacy, a music consultancy.

“If you have music venues that are struggling with licensing issues, then that doesn’t mean that a city is thriving. Every city has music schools, venues, and most have studios, rehearsal spaces. But very few cities have music policy infrastructures.”

Sound Diplomacy, which works with cities to develop music policies, wants to encourage local authorities to start thinking of music as an infrastructure – as you would education, health or transport.

“Music is a mixture of hardwiring and softwiring,” Shapiro says. “We need infrastructure for it to survive, but we need networks to be created, we need people to recognise it’s a value.”

He believes London is still a thriving music city: venue closures have stalled in the last three years, and the appointment of a night tsar in 2016 shows the city considers music to be intrinsic to its future, with creative industries worth £47bn to London’s economy.

“Music is in our DNA,” says Justine Simons, London’s deputy mayor for culture and chair of the World Cities Culture Forum. “There’s punk in the 70s, and today you can think about grime and how that’s projected London into the world stage.”

She says there’s a “recognition that if you want to be a successful city you can’t do it without culture”. For the first time, music has been brought into the mayor’s London Plan, and London has adopted the Agent of Change principle, first established in Australia: if a housing development is built next to an established live music venue, it is the developer that must pay for soundproofing; if you move next door to a club, you must accept that there’s going to be noise.

Other cities can stake claims to particular scenes and sounds. Liverpool gave the world the Beatles, Memphis was home to the Stax and Sun record labels, and New Orleans is the birthplace of jazz. Techno came from the warehouses of Berlin and Detroit, the roots of salsa go back to Santiago de Cuba, Varanasi has a rich history of classical Indian music, Nashville is country. Hamamatsu takes a different tack, styling itself as Japan’s city of music because it is home to a number of instrument manufacturers, notably Yamaha.

Emma-Lee Moss, a singer-songwriter who performs as Emmy the Great, has lived in New York, London, Los Angeles and Hong Kong. For her it was New York that was the “loudest” when it came to musical heritage.

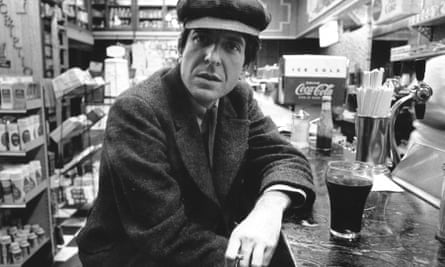

“On a single day, I could have taken the subway past the J and the Z – the trains Jay-Z drew his name from – then walked through Central Park and past the Dakota, where John Lennon lived and died,” she says. “You could imagine Patti Smith stalking the East Village, Dylan swinging his guitar on the other side in Greenwich Village, [Leonard] Cohen in the Chelsea Hotel. You could see TV on the Radio still walking to and from their practice space in Brooklyn, Princess Nokia throwing soup on racists on the L train.

“Every generation of new artists staked their claim on a piece of land, and as long as they were still alive, they were still there, street-level.”

That kind of heritage is key to music cities: 70% of tourists to Memphis cite music as the main reason for their trip. But history alone doesn’t make a thriving, sustainable place for music. Nashville is struggling with gentrification and inequality that affects the artists who call it home. “It’s systematically tearing down Music Row – studios are being bought, sold, and turned into flats,” says Shapiro. “It’s a music city – it’s Nashville – but what are they doing to maintain it?”

New Orleans, by contrast, is one of the most exciting cities for live street performances – but has never had a music policy of any kind to guide venues and musicians. Shapiro thinks this situation penalises artists.

“The reason why so many artists play on the street is because there is a structure in place that doesn’t allow them to play inside,” says Shapiro. “Playing on the street in an unregulated way, to me, is an example that something must be wrong with the music venue infrastructure. Passing round a bucket is not sustainable.”

A strong musical heritage also brings the risk of marginalising other genres. As the home of Bollywood, Mumbai has a strong culture of traditional music, but some residents feel they’ve struggled to carve out an alternative scene because Bollywood music is so dominant. Tucked away in the city’s Bandra district is Adagio, a music centre started by a couple of friends who loved rock.

“The music here is commercial Bollywood music, or we have our classical music, but there’s no space for rock’n’roll,” says Kastik Gopalakrishnan, 24, of Adagio. Each week he hosts a vinyl listening where anyone can listen to a whole record together in silence – Pink Floyd, the Beatles, the Carpenters, the Stones. “It’s such a beautiful vibe, everyone just sitting down. Pin-drop silence.”

It is the only space like it in the whole city, he says. “Even when we started playing the instrument, our parents would be like, ‘We don’t want to listen to this, play me something classical.’ And we decided there’s no scene for rock’n’roll, no one listens to this kind of music, so that’s why we wanted to start the vinyl thing – we’re fighting for the cause.”

It seems clear that music will always thrive wherever there are people listening and performing. Going by that rule, Melbourne is the most musical city, as it boasts by far the most performances per year – well over 73,000, according to Music Victoria. It is followed by New York, with 36,192 performances, Paris with 31,375 and London with 22,828 – although the figures, compiled by the World Cities Culture Forum, come from different sources and are not strictly comparable.

Then again, maybe it doesn’t come down to numbers at all, but rather the strength and vibrancy of a city’s music community – a much harder thing to quantify.

Moss says she found it easiest to make a living as a musician and collaborate with others in New York. Every city, however, has “rhythms and hums and vibrations that exist in its landscape”, she says.

“There are the ghosts of the music that has been made there, and the imprints of musicians who have walked its streets.”

Follow Guardian Cities on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram to join the discussion, catch up on our best stories or sign up for our weekly newsletter