Editor's note: This story originally appeared in the June 25, 2017, edition of the News Tribune. It has been lightly edited for today's readers.

DULUTH — For authorities, the case that would become the notorious Glensheen murders began on a warm, muggy summer morning.

It was just before 7 a.m. on June 27, 1977, when nurse Mildred Garvue arrived at Glensheen mansion on London Road to start her day shift caring for elderly heiress Elisabeth Congdon, who needed round-the-clock nursing care after suffering a stroke.

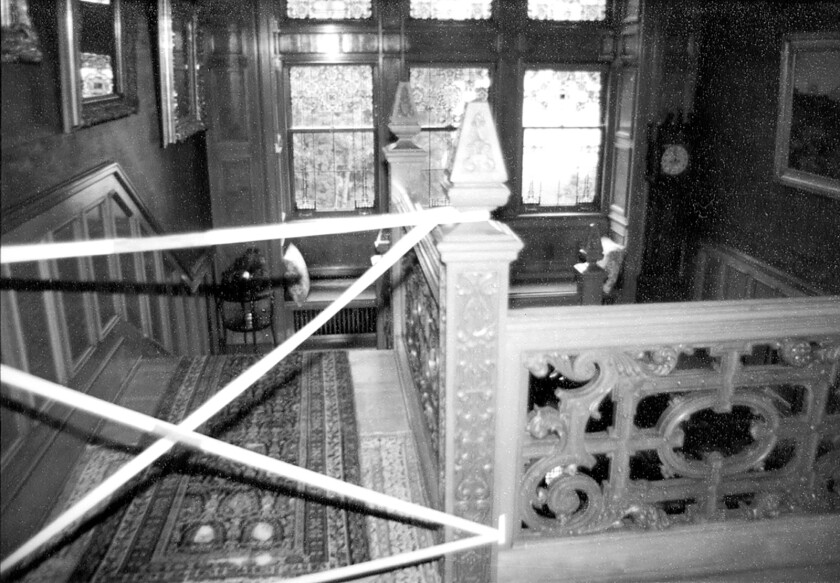

To Garvue's surprise, the front door was unlocked. She turned the knob and went in. Across the foyer, on the landing of the grand staircase, she saw Velma Pietila, the night nurse, sprawled on the window seat. Pietila, 67, had retired a month earlier and was filling in for a sick nurse.

For a moment, Garvue thought Pietila had fallen asleep there. But as Garvue mounted the stairs, she came across a bloody scene from a fatal struggle that had started at the top of the stairs on the second floor and continued down to the landing. Pietila had been viciously hit 23 times with a heavy brass candlestick. Most blows were to her head.

ADVERTISEMENT

Alarmed, Garvue continued on to Congdon's second-floor bedroom. There, she found Congdon in her bed. A satin pillow covering her face had been used to suffocate her.

At 83, Elisabeth Congdon was the last surviving child of Chester Congdon, who made a fortune in mining in the late 1800s and early 1900s. She was the last family member to live in the grand mansion he had built at 3300 London Road.

With no eyewitness or confession, police put together a circumstantial case from a trail of clues left in Duluth; Bloomington, Minn.; and Colorado. News accounts, court documents, trial testimony and the book "Will to Murder: The True Story Behind the Crimes & Trials Surrounding the Glensheen Killings" reveal how it unfolded:

The police investigation quickly focused on Elisabeth's daughter by adoption, Marjorie Caldwell, 44, and Marjorie's husband, Roger, 43, in a murder-for-inheritance plot. The Caldwells, who had been married a year, lived beyond their means and were deep in debt. At the time of the murders, the couple's financial straits had worsened. Their home, furniture and vehicles had been repossessed, and they were living in a motel in Golden, Colo.

Marjorie stood to inherit $8.2 million when her mother died. In the previous 10 years, she had gone through more than $2 million. Her frequent requests for advances on her inheritance and her spendthrift ways had become an irritation for Congdon trustees. A month before the murders, Roger Caldwell traveled to Duluth to ask Congdon trustees for $750,000 so the couple could buy a horse-breeding ranch. He brought a bogus letter from a doctor claiming the Caldwells needed to live on a ranch for Marjorie's youngest son's health.

They didn't get the money. They also didn't get the $250,000 Roger Caldwell asked for just 10 days before the deaths to hire attorney F. Lee Bailey to ward off criminal charges against them. The couple were under investigation for insurance fraud. Marjorie was suspected of arson fires at a Colorado bank that had denied her loans. Roger had bounced checks and fraudulently used credit cards. And Marjorie had been sued several times.

Tightening time frame

At Glensheen, an intruder had apparently broken a basement window to gain entry on the night of the killings and gone up the main staircase, where he encountered Pietila during her 11 p.m. to 7 a.m. shift . A nylon stocking wrapped around one of her wrists suggested the intruder had tried to tie her wrists. But she fought back and was viciously beaten to death. The murderer cleaned up in the nurse's room across the hall from Elisabeth's room. He took a small wicker suitcase and jewelry from Elisabeth's room, including the watch and ring that Elisabeth was wearing. He left through the front door and drove to the Minneapolis-St. Paul International Airport in Pietila's car.

The maid and cook who lived at one end of the house heard nothing, though the cook's dog began barking at 2:50 a.m. and remained agitated for two hours. Pietila's wristwatch stopped at 2:40 a.m, the possible time of her murder.

ADVERTISEMENT

At the Twin Cities airport a few hours later, car keys with Pietila's name on the key ring were found in a trash receptacle. A parking lot ticket stamped 6:35 a.m. that day also was found in the container. A while later, Pietila's car was located in the short-term lot.

Meanwhile, Roger Caldwell wasn't seen coming or going from his motel room in Golden, Colo., but Marjorie was. She was looking at real estate and giving differing accounts of her husband's whereabouts. After being informed of her mother's death on June 27, she looked at more real estate.

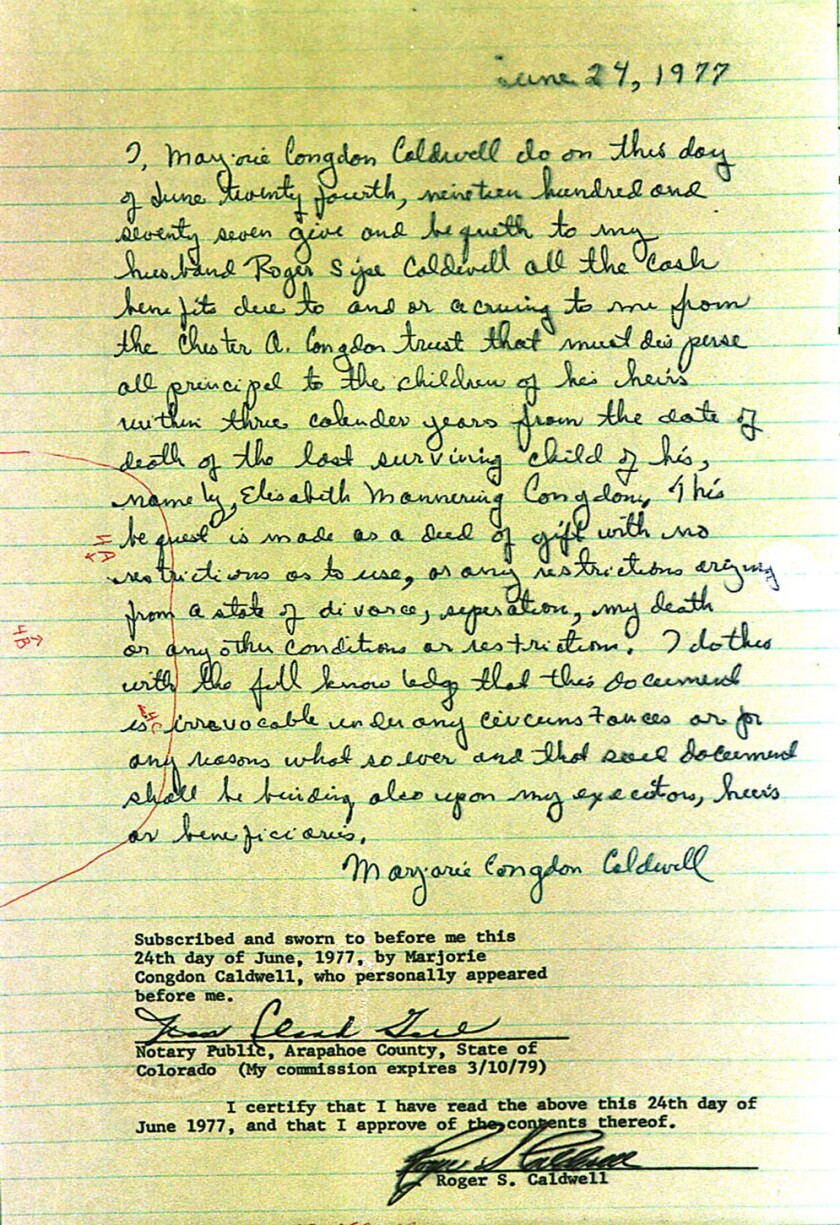

The next day, Roger Caldwell was back in Colorado, opening a safe deposit box at a bank in Golden, looking agitated and with disheveled hair. He had two cuts on his face and a swollen hand, injuries he didn't have two days earlier. With a search warrant, police later found a notarized letter in the safe deposit box that had been signed by Marjorie Caldwell three days before the murders. It irrevocably gave Roger Caldwell a $2.5 million cut of her inheritance upon the death of her mother.

John DeSanto, the assistant St. Louis County attorney who prosecuted the murder cases against the Caldwells, called it the closest thing to a murder contract he's ever had.

The Caldwells returned to Duluth for Elisabeth Caldwell's June 30 funeral, staying at the downtown Radisson Hotel. After they checked out that day, police searched it and found a receipt for a $54.86 purchase from a Twin Cities airport gift shop on the day of the murder. Gift shop clerks said it was for the purchase of a garment bag made at 6:40 a.m. by a man matching Roger Caldwell's description.

After leaving Duluth the day of the funeral, the Caldwells traveled to the Twin Cities, where they stayed at a Bloomington hotel. There, Roger Caldwell collapsed and was taken to a hospital where a high level of sedatives was found in his system. The sedatives were similar to those found in an unresponsive Elisabeth Congdon three years earlier after Marjorie fed her mother a sandwich made with her homemade marmalade. Elisabeth survived, and the incident wasn't pursued after the sandwich and suspect marmalade couldn't be found.

While Roger Caldwell was recovering in the hospital, police searched the couple's Bloomington hotel room. They found the garment bag purchased at the airport. They also found the small wicker suitcase and 25 pieces of jewelry taken from Elisabeth Congdon's room, including the watch and diamond and sapphire ring she had been wearing. Marjorie had long admired and wanted that ring. She told police the jewelry wasn't stolen, but were copies of her mother's jewelry.

Meanwhile, a handwritten envelope addressed to Roger Caldwell arrived at their Colorado motel, postmarked in Duluth on the day of the homicides. The motel clerk gave it to police. Inside was a 1,700-year-old Byzantine coin taken from a memorabilia case in Elisabeth Congdon's bedroom. Handwriting experts concluded Caldwell - who had a coin collection - had addressed the envelope.

ADVERTISEMENT

Hair and blood found near the dead bodies were "consistent with" Roger Caldwell's hair and blood type, the closest match possible in the 1970s. Today, DNA analysis can positively identify blood, hair, saliva, hair and other biological material to connect a suspect to a crime. The defense would argue at trial that the hair was left during Roger's previous visit to the house. But he hadn't been in that part of the house, the prosecution would counter. Police never found Caldwell's fingerprints in the house, leading police to conclude he wore gloves.

One conviction, one acquittal

Nine days after the slayings, Roger Caldwell was arrested and charged with two counts of attempted first-degree murder. He was found guilty in a 1978 trial that was moved to Brainerd because of pretrial publicity. He was sentenced to two life terms. The next day, Marjorie was charged with murder conspiracy and aiding and abetting murder. In her 1979 trial held in Hastings, Minn., she was found innocent of all charges. Jurors apparently liked the chatty, outgoing heiress, because they partied with her after the verdict.

The Caldwells were represented by high-powered defense attorneys from the Twin Cities - Ron Meshbesher for Marjorie and Doug Thomson for Roger - who attacked police procedures, argued the crime scene was contaminated and claimed the Caldwells were framed. Neither Marjorie nor Roger testified at their trials.

Police had made mistakes.

Too many people were allowed access to the crime scene, especially on the first day. There were lapses. Officers discarded cigarette butts in the toilet in the nurse's bathroom where the murderer had cleaned up. A palm print on the sink turned out to belong to the lead police investigator. And a dog was allowed to jump through the apparent entry window to follow a scent.

Duluth police procedures improved as a result. Fewer people are now allowed at crime scenes. Detectives are apt to keep their hands in their pockets or wear gloves when they survey a crime scene. Officers write reports on every lead pursued and interview completed even if nothing relevant results. And photos, fingerprints and other evidence are better documented.

During Marjorie's trial, a key piece of evidence that helped convict Roger was discredited. A fingerprint on the envelope containing the stolen coin that was mailed from Duluth turned out not be Roger's, as earlier believed. It was important evidence because it placed Caldwell in Duluth on the day of the murders.

Because of the fingerprint revelation, the Minnesota Supreme Court threw out Roger's conviction in 1982 and sent the case back to Duluth for a new trial.

ADVERTISEMENT

That led to the controversial 1983 plea bargain that freed Roger after five years served. In exchange for guilty pleas to two counts of second-degree murder and a confession, he got no additional prison time. His confession, however, yielded no new information. He failed to implicate Marjorie or a possible third conspirator. He said he went to the Congdon mansion to steal, not kill and that he acted alone.

DeSanto has long regretted the deal, which he agreed to because he feared losing a retrial. Instead of accepting the plea, he says he should have walked away and tried the case again.

"I don't think Roger did this alone," DeSanto said. "I believe he met an accomplice in Duluth that helped him. ... The purpose was to murder Elisabeth Congdon for the inheritance. They didn't want to kill Velma, but she fought to her death. I think they were going to tie her up."

He also thinks they may have had a key to get into the house and that the broken window was a ruse to make it look like a break-in.

The case lacked evidence that clearly placed Roger Caldwell in Duluth on the night of the murders. But police had it. A cab driver had picked up a rider at the Greyhound Bus Depot in downtown Duluth between 11:30 p.m. and midnight that night. As directed, he drove the man down London Road, five blocks beyond Glensheen mansion. The cab driver later identified Roger Caldwell from a physical lineup as the rider. But because he had seen a photo of Caldwell in the paper, a judge ruled the identification was tainted and inadmissible.

But the envelope that had been mailed from Duluth containing the stolen coin still held some secrets. Typically, evidence from a case is destroyed after trials and appeals are exhausted. But DeSanto kept some of the evidence from the Caldwell cases, including the envelope.

In 2003, before "Will to Murder," which DeSanto co-authored, was released, DNA testing was done comparing saliva residue on the envelope's seal with a surviving saliva sample from Roger Caldwell. Those results were combined with analysis of blood from the crime scene believed to be the killer's. The results showed a 99.9% chance the saliva and blood came from Roger Caldwell.