Mehmed II (1432-1481 CE), also known as Mehmed the Conqueror, was the seventh and among the greatest sultans of the Ottoman Empire. His conquests consolidated Ottoman rule in Anatolia and the Balkans, and he most famously triumphed in conquering the prized city of Constantinople, transforming it into the administrative center, cultural hub, and capital of his growing empire. His victories would mark the end of the Byzantine Empire and usher a new era of Ottoman dominance in the Eastern Mediterranean.

Early Life & Family Origins

Born on 30 March 1432 CE, Mehmed was the third son of Sultan Murad II (r. 1421-1451 CE), and Hüma Hatun, a concubine of Balkan origins from Murad's harem. His paternal grandfather was Mehmed I (r. 1413-1421 CE) and traced his ancestry back to Osman I (r. 1280-1323 CE), the founder of the Ottoman Dynasty. Mehmed's name was derived from the name of the Islamic Prophet Muhammad (570-632 CE), and unlike the naming customs of other Islamic cultures, in Turkish tradition, the name Muhammad was generally reserved for the Prophet himself.

Mehmed spent his early childhood in Edirne, until he was moved to the Black Sea city of Amasya and replaced his brother Ahmed as the governor of the province in 1437 CE after his death, despite being five years old. Mehmed's status as a child of the sultan afforded him the opportunity to study under the best scholars of the region. He had many tutors throughout the years, teaching him theology, history, foreign languages, among many other topics. These personal tutors reserved specifically for Ottoman royalty were referred to as lalas and played an essential role in preparing Ottoman royals for the intricacies of administration. Mehmed's readings of various Islamic writings would have a significant impact on his ambitions as a sultan. His desire to conquer Constantinople was inspired by the writings of Arab writers Al-Kindi, Ibn Khaldun, and further cultivated by a hadith (or saying) attributed to the Prophet Muhammad, who prophesized a Muslim army would conquer the city.

Ascension to the Throne

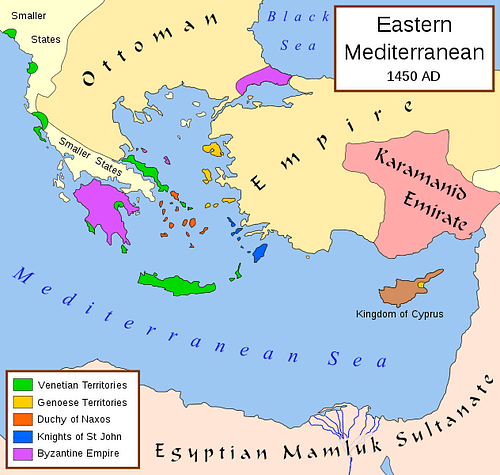

Mehmed's father, Murad II's reign, was embroiled in conflict from its onset, both domestic and foreign. During the start of his reign, Murad fought in a war of succession against one of his brothers, who, with the support of the Byzantine Empire (Eastern Roman Empire) and other Balkan Christian states, led a revolt in the European part of Ottoman territory. After crushing the uprising, he fought wars against Turkic states such as the Karamanids to the east, and the various European powers such as the Venetians, Hungarians, and crusaders in the west. These prolonged conflicts, along with the death of his favorite son Alaeddin (d. c. 1444 CE) took a toll on Murad, and he decided to retire in Bursa in 1444 CE and relinquished the throne to Mehmed, who was 12 years old at the time.

The rivals of the Ottomans and various domestic factions saw the reign of the child sultan Mehmed as an opportunity to further their interests. In 1444 CE, Pope Eugene IV (r. 1431-1447 CE) began mustering forces for a new crusade after absolving a previous peace treaty with Murad. Meanwhile, the Despots of Morea, rulers of a small Byzantine territory in Southern Greece, began incursions into Ottoman Thessaly. These events led to a crisis within the inner circles of high-ranking Ottoman officials. Convinced by the influential grand vizier Halil Çandarlı (d. 1453 CE) and a letter from Mehmed himself, Murad returned to the throne to deal with the threat.

The crusaders led by the Polish King Wladislaus III (r. 1434-1444 CE) and Murad's forces clashed at the Battle of Varna in 1444 CE, which ended in a decisive victory for the Ottomans. During this time, Mehmed retreated to his studies under his tutors Zaganos Pasha (d. 1462 CE) and Shahabuddin Shahin Pasha. In 1451 CE Murad II died, leaving the throne to Mehmed in his will. Shortly after this, Mehmed set his eyes on the biggest prize in the region, the city of Constantinople.

Siege of Constantinople

Constantinople itself was a husk of its former glory, the population reduced by plagues, constant sieges, and the loss of the surrounding territory made the city more of a symbolic target rather than a strategic one. Many of Mehmed II's predecessors attempted to conquer the city but to no avail. A short occupation after the Fourth Crusade aside, it remained nearly impregnable over the centuries, mostly due to the Theodosian Walls, a series of fortifications built by the Byzantine emperor Theodosius II (r. 402-450 CE).

Before the siege, Mehmed II renewed his peace treaties with many European states and the Karamanids. Then he began preparations to besiege the city in the winter of 1452 CE by building a navy in Gallipoli and then mustering forces in Thrace. In the spring of 1452 CE, he strengthened his stranglehold on the Byzantine capital by constructing a new major fortress across the Golden Horn near Pera, which is known today as Rumelihisari. It complemented the fortress Anadoluhisari, which was built by Mehmed's predecessor Sultan Bayezid I (r. 1389-1402 CE), across the Bosporus on the Asian side.

Emperor Constantine sent out pleas for aid. In early 1453 CE, the Genoese and Venetians pledged to bolster the Byzantine naval garrison with some warships. Pope Nicholas V (r. 1447-1455 CE) also offered his assistance but with the stipulation that the Eastern Orthodox Byzantines had to recognize the authority of the Roman Catholic Church and eventually unite. This deal did not come to fruition; however, various independent Christian volunteers joined the defense.

The Constantinople garrison of c. 5000-7000 soldiers was rather overstretched over the long perimeter of the Theodosian Walls, with Genoese General Giovanni Giustiniani (d. 1453 CE) at their helm. Emperor Constantine commanded a contingent of his forces near his palace complex. A detachment of Turkish rebel forces headed by Mehmed's cousin Prince Orhan vying for the Ottoman throne also joined the city's defense. In preparation for the Ottoman's imminent assault, the Byzantines stretched a long chain across the Golden Horn, which served to block enemy warships from attacking vulnerable parts of the wall from the sea.

Mehmed II arrived with the remainder of his forces on 5 April 1453 CE. His army numbered around 80,000 men, including specialized infantry, cavalry, siege equipment, and naval forces. Making up the vanguard of the Ottoman assault was the formidable Janissary Corps. The Janissaries were made up of Balkan Christian children who were plucked away from their families and trained to eventually become career soldiers under the devşirme system. Much like the Varangian Guard, who served Byzantine emperors, the Janissaries were chosen for their steadfast loyalty to the sultan above all. Other forces included irregular soldiers such as the infamous Başıbozuk and Azap infantries, and Akıncı horse raiders, while the rest of the army consisted of regular infantry, Sipahi cavalry, and allied Serbian forces.

Several weeks after the siege began on 6 April, the defenders of the city rallied by Giustiniani successfully fended off many Ottoman attacks despite the overwhelming odds against them. The Ottomans used their cannons to blast sections of the wall to great effect; however, the long cooldown period of the cannons generally allowed the Byzantines to repair breached parts quickly. A new strategy was necessary for the Ottomans, and Mehmed crafted an ingenious solution to the Byzantine naval blockade in the Golden Horn. On 22 April, he ordered his naval forces to circumvent the Byzantine chain by using oxen to drag his warships across the land in Pera and pushing them back into the sea inside the Golden Horn.

Mehmed launched his attack in three waves. The first was led by his Başıbozuk and Azap infantry, who were handily repelled, but fatigued the defenders. During the second wave of assault led by regular infantry, the Ottoman cannons managed to blast through a section of the outer wall. The second wave, too, was repelled, however, quickly taking advantage of the opening in the wall, Mehmed sent his Janissaries to spearhead the final push into the city. Byzantine morale was shattered when Giustiniani was mortally wounded during the clashes, allowing the Janissaries to establish a foothold and plant their flag on the wall. Emperor Constantine tried to lead his men on a last-ditch effort, but he fell in battle and the defenders began to rout. Thus, 29 May 1453 CE marked the fall of Constantinople.

Consolidation of Power

Following the ghazi traditions, the Ottoman troops were allowed to sack the city for three days. After the third day, Mehmed made his triumphant entry into the city through the Gate of Charisius; his procession went directly to the Hagia Sophia, which would be converted into a mosque.

To restore the population of the city, the sultan issued an edict relocating people from Anatolia and the Balkans into his new capital, regardless of ethnicity or religious origin, and he ordered many of the same soldiers that fought in the siege to restore damaged infrastructure. He also oversaw the building of a new royal palace, which would be known as Yeni Saray, and later on as Topkapi Palace. Caroline Finkel describes Mehmed's new headquarters:

His palace provided Sultan Mehmed with seclusion. Here he cultivated an aura of mystery and power, which regulations issued towards the end of his reign were designed to enhance. (89)

Mehmed now began the task of purging dissenting factions and those who could challenge his authority. Among the first to be charged was Grand Vezir Halil Çandarlı. The power of the grand vizier was also weakened, with many of its responsibilities delegated to other high-ranking ministers. Mehmed then reallocated much of the land and property of the nobles to his slave class to counterbalance the influence of the former, and to cement the loyalty of his slaves.

Later Conquests & Death

Soon after Constantinople fell, the Genoese colony city of Pera (now known as Galata) surrendered peacefully. With his dream of conquering Constantinople realized, Mehmed set his sights on new targets. In the spring of 1454 CE, he began a campaign in Serbia to annex territories under the Hungarian sphere of influence. Mehmed's made limited progress, the city of Novo Brdo, famous for its rare ore deposits, was captured, but the campaign was called off after Hungarian forces began mobilizing near the border.

Mehmed would make several more incursions into Serbia, during which his first major defeat was dealt in the Siege of Belgrade in July of 1456 CE. However, Mehmed's final attempt in subjugating Serbia was successful when in 1459 CE, the Ottomans took control of the fortress of Smederevo. The rulers of the now-dissolved Despotate Serbia were exiled, and the frontier territory near the Hungarians was stabilized.

In the years following his success in Serbia, Mehmed began absorbing Byzantine remnant states in Greece, and the Black Sea coast. He conquered Attica in early 1459 CE, and in May of 1460 CE, he dispatched a force to intervene in a civil war in Morea. With these conquests, only a small strip of land on the Black Sea coast controlled by the Empire of Trebizond remained as the last vestige of Byzantine rule in the region.

Trebizond and its surrounding region were conquered in 1461 CE, and this expansion eastward brought the Ottomans bumping heads with the remaining Anatolian Beyliks. Much like the situation in Morea that prompted Mehmed's intervention, the Karamanids, too, were plunged in a civil war. Mehmed's conquest of Karamanid territory brought another powerful eastern neighbor, the Akkoyunlu Confederation, into conflict with the Ottomans. The clashes would continue for decades until, in 1501 CE, Mehmed's son and successor Sultan Bayezid II (r. 1481-1512 CE) would defeat them.

Perhaps the most noteworthy of Mehmed's conflicts after the conquest of Constantinople was in Wallachia, where his struggles reining in the ruthless prince Vlad III would serve as a possible inspiration for the settings of the novel Dracula (1897 CE) written by Bram Stoker. Vlad led Wallachian resistance against Mehmed's forces and was known for his cruel methods of execution, massacring entire populations of settlements standing in his way, earning him the name Vlad the Impaler. His notoriety would spread across Europe, and he would eventually be captured and imprisoned by the Hungarians. He would be released sometime later, only to perish in battle in 1476 CE.

The final years of Mehmed's reign would be marked by continuous conflict. Invigorated by their past successes, the Ottomans would wage a long war against the Venetians (1463-1479 CE), over their holdings in Southern Greece and the surrounding islands. The war would also spill over into Albania when legendary Albanian resistance leader Skanderbeg (r. 1444-1478 CE) seeking to keep Albanian independence from the ever-expanding Ottomans secured an alliance with the Venetians. However, these wars would conclude in a strategic victory for the Ottomans. After seizing Venetian possessions in the Aegean and their defeat at the key fortress of Negroponte, their presence in the region was greatly diminished. Skanderbeg died in 1478 CE, after resisting the Ottomans for decades. His death would leave a power vacuum in Albania, and contributed to the cascade of events that would eventually lead to the eventual conquest of Albania by the Ottomans. In the spring of 1481 CE, Mehmed led a new expedition with his army. During the march, he fell ill, and on 3 May 1481 CE, he passed away. Mehmed's eldest son Bayezid II would succeed him as sultan.

Government Administration & Religious Affairs

Mehmed II made huge strides towards centralizing Ottoman rule and expanding the role of the sultan. He consolidated his power through weakening and redelegating the roles and responsibilities of high-ranking officials who would also be bound to the sultan through political marriages. Wealth and land from the aristocrats was redistributed to Mehmed's slave class, giving him a reliable and loyal base and having the additional benefit of a check on the power of any conspiring nobles. Mehmed and his imperial council convened in regular meetings known as the Divan, named after the floor-level couches adorning the room.

One development during Mehmed's reign, which is more famously attributed to future Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent (r. 1520-1566 CE), is the compilation of law codes, replacing vague progenitors. These secular law codes, known as kanun, dealt with topics such as the power structure of the government and taxation of subjects and were carefully formulated not to clash with religious law (şeriat).

Mehmed's administration had a moderately hands-off approach regarding religious affairs. Non-Muslim populations living in the Ottoman Empire were allowed to practice their faith freely but were required to pay a special tax called cizye. Furthermore, seeking to legitimize his rule over the largely Eastern Orthodox minority, Mehmed appointed religious leaders aligned with his self-interests such as the Patriarch of Constantinople Gennadious Scolarious (r. 1454-1464 CE) and gave them wide-reaching authority over their religious adherents.

Legacy

Throughout his reign, Mehmed II enacted sweeping administrative changes, reorganization of military forces, ambitious construction projects, and broad conquests, leaving his successors an empire to be reckoned with, but he was also known as a benefactor of artists and authors. He read classical Greek and Roman literature as a child and continued to collect and read relevant manuscripts throughout his reign as sultan. He supported dozens of poets, writers, and scholars, and invited philosophers, astronomers, and painters from across Europe and the Middle East to his court. John Freely describes his court's opulence as:

Both the sultan and the greatest of his grand vezirs were men of culture and patrons of the arts, and the Conqueror's court in Istanbul rivalled in its brilliance that of Western princes of the European Renaissance. (119)

During his reign, he also undertook many bold architectural undertakings, which included repairing his new capital's broken infrastructure, building the lavish Topkapı Palace, the Grand Bazar, and overseeing the construction of several mosques built in his honor, the most famous of those being Fatih Camii (Mosque of the Conquerer). It is said that when he entered the city of Athens after its conquest, he ordered the renovation of all ancient buildings that were deteriorated by the elements.

Mehmed II's conquest of Constantinople earned him the title Fatih (conquerer) by his subjects. Contrary to popular belief, Constantinople's name was not changed to Istanbul by Mehmed; it was referred to by the Ottomans as Konstantiniyye, derived from the Arabic name of the city. Istanbul was the Turkish colloquial pronunciation that was officially adopted by the Republic of Turkey after the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire.