|

31st Emperor of the Roman Empire | |

| Predecessor | Messalla |

| Caesar of the Dominium Caesaris | Maxentius |

|

2nd Caesar of the Dominium Caesaris | |

| Predecessor | Aelianus |

| Successor | Maxentius |

| Born | September 250 Sirmium, Pannonia Inferior, Roman Empire |

| Died | 325 |

| Religion | Roman paganism |

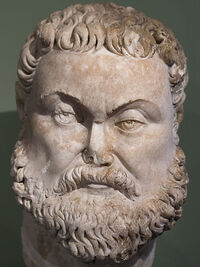

Marcus Aurelius Valerius Maximianus (Maximian) was a Roman Co-Emperor from 289 to 315. Maximian was Caesar (subordinate emperor) from 289 to 308 and Supreme Senator from 308 to 321.

Early Life[]

Great Roman Civil War[]

Reign of Messalla with Aelianus[]

Reign as Caesar[]

Reign as Supreme Senator[]

Role of Diocles[]

The ascent of Maximian to senior emperorship increased the importance of Diocles Valerius, a longtime friend of Diocles who had been very influential within the Roman government ever since Messalla had appointed Maximian Caesar. Diocles had long been a trusted advisor to both Messalla and Maximian, but he had always had less influence over Messalla than Maximian. Messalla had sometimes overruled edicts and appointments made by Maximian. Also, Maximian only had authority within the Dominium Caesaris. Maximian's rise to the position of Supreme Senator meant that Diocles had strong influence over a man whose decisions were binding throughout the Roman Empire and could only be vetoed in rare cases. Diocles also had influence over Maxentius, both because Maxentius was the son of Maximian, and because Diocles had become friends with Maxentius himself. In essence, the death of Messalla led to Diocles becoming Roman emperor in everything but name. During the time that Maximian ruled with Maxentius, most policies that those two emperors enacted were either formulated or heavily influenced by Diocles.

Personality Cult []

For several years before Messalla's death, Diocles had been building a personality cult centered around Messalla and to a lesser extent Maximian. Messalla neither endorsed nor opposed this during his lifetime. After Messalla died, the personality cult intensified. Rome had had an imperial cult since the time of Augustus, but what Diocles advocated was for the imperial cult to be augmented to portray Messalla as greater than all previous emperors except Augustus.

According to the Diocles' propaganda, Messalla had saved the Roman Empire from collapse and restored the empire's past glory. He was portrayed as the personification of the values that had made Rome great in the past, and the representative of the gods on earth. History was rewritten to improve the image of Messalla: the political instability that preceded the Great Roman Civil War was exaggerated, and Aurelian's reforms were downplayed. In the past, the emperor had been portrayed as a first among equals, but Messalla was portrayed as fundamentally different from other humans — he was portrayed as the representative of the gods while he was alive, and having become a god after his death. Similarly, the system of dual rulership was described as ordained by the gods, the appointment of Maximian as Caesar was described as being directed by the gods, and Maximian (and by extension all subsequent successors of Messalla) were portrayed as inheritors of the role of the intermediary between the gods and the people.

Maximian initially declined to accept the honors that Diocles was heaping on him, but he changed his mind by 311. Maxentius was more quick to accept the notion that he and his father were innately superior to the masses. In accordance with this idea, the two emperors ordered huge palaces to be built for themselves, began wearing ornate purple robes and golden crowns, and instituted elaborate court ceremonies. Temples began to be built in honor of Messalla. May 30, the anniversary of the end of the Great Roman Civil War, was declared the Feast of Messalla.

Economic Policies []

By the time Messalla died, the Roman economy was still recovering from the wars and rebellions of the 270s and 280s. The public works program had done little to lift people out of poverty, and the currency reform had failed to stop inflation. Out of frustration, Diocles began formulating more radical economic policies, and the emperors happily accepted most of Diocles' proposals.

Monetary Policies []

The new denominations of coins that were introduced under Messalla's authority were still less common than the older, debased coins by the time Messalla died. Even those who had significant amounts of the new coins tended to use them only to pay for significant transactions, and used debased coins to finance mundane transactions. To complicate matters, Messalla had never specified a rate at which debased coins could be exchanged for new ones; and different quantities per capita of follii (bronze coins) and copper coins were minted in different jurisdictions, which meant that the values of the different coins in practice deviated from the official standard in most parts of the empire.

In April 309, Maximian issued an edict titled the Edict on Coinage, which outlawed the debased coins and ordered that the debased coins be confiscated and replaced by minting coins of the new denominations by the end of the year. The edict also declared one laureatus equal to one hundred antoniniani or two hundred denarii.

What Maximian (and Diocles, who proposed the edict) did not know was that the actual value of the new coins in terms of the old ones was higher than the official rate in some places and lower than others. In places where there were not enough new coins, either holders of the old currency were undercompensated for the confiscation, or more of the new coins than necessary to meet the prescribed ratio were minted. Another issue was that the majority of the new coins was of the bronze and copper denominations, and very few of the new coins were solidi (gold coins). This exacerbated the growing problem of the devaluation of the bronze and copper coins relative to the gold and silver coins. Another problem was that the amount of the new currency an individual was entitled to receive was deducted by the amount that he or she already possessed, which meant that much of the old currency was taken without compensation. Since the old currency was still used for everyday transactions, this uncompensated confiscation amounted to losses of wealth for the parties affected. Also, in some provinces, some individuals who had considerably more of the new currency than the equivalent amount of the old currency had the excess amount of the new currency taken from them.

During 309 and 310, wages and prices for every kind of good or service fluctuated wildly as the old coins were replaced people struggled to correctly value things exclusively in terms of the new currency. At Diocles' suggestion, Maximiam responded by issuing the Edict on Acceptable Prices, which set price ceilings and price floors for more than two thousand products and services. As this law was based on ignorance to the law of supply and demand, it led to surpluses and shortages all over the empire.

Taxation []

Diocles proposed reforms to the imperial tax system during early 311. Whereas all of Italy had previously been exempted from taxation, Diocles proposed that only Rome and its suburbs be exempt. At the same time, he proposed that Thessalonica, the capital of the Dominium Caesaris, be granted exemption from taxation. Diocles also proposed allowing taxes to be paid in various kinds of goods in lieu of money.

The tax plan was first accepted by Maxentius in May 311. Maximian began implementing the proposal in November 312.

Attempts at Economic Planning []

By 314, the price controls were yielding disastrous results. Many people were refusing to sell underpriced goods and unable to buy artificially overpriced goods. Black markets were also developing. To address this problem, Diocles proposed requiring governors to collect information about the types of goods and services that were rare in their respective provinces; compel people to enter, remain in, or leave certain trades or occupations; and confiscate and distribute goods that people would not voluntarily sell.

Maxentius quickly began ordering his governors to implement the policy. Maximian never officially adopted the policy, though many of his governors did. In several provinces, the governors ordered that producers be compensated for goods taken for redistribution. Also, several governors in Italy and Africa pursued an alternate policy: taxing the richest inhabitants of their provinces and redistributing the money and in-kind payments.

Persecution of Christians []

Precursors []

Christianity had been growing rapidly in the Roman Empire since the 270s. By the 290s, the imperial government began to take notice. In 297, Messalla disqualified Christians from serving as governors or praetorian prefects; and during the 290s, several governors and two praetorian prefects (one of whom was Diocles) carried out purges of the army and bureaucracy within their respective jurisdictions.

Despite this discrimination, Christianity continued to spread. Diocles continued to urge Messalla and Maximian to stop the growth of Christianity. Neither of them did anything until 303, when Maximian made it illegal to proselytize Christianity within his territory. Messalla extended this ban throughout the empire a year later. No other actions were taken against Christians at the imperial level for years, although Maximiam, at Diocles' encouragement, appointed three anti-Christian praetorian prefects. Diocles, who was praetorian prefect of Illyricum from 302 to 307, made laws within Illyricum that made Christians second-class citizens in every way; and the three praetorian prefects who were appointed upon Diocles' recommendation, as well as the governors of several Italian and African provinces, followed suit within their jurisdictions.

Government discrimination escalated after Maximian became Supreme Senator. By the end of 309, Maxentius had issued an edict stripping Christians of their rights throughout the Dominium Caesaris. At the same time, the punishment for proselytizing Christianity was steadily becoming more severe in many areas: though Messalla's edict against proselytism only called for violators to spend three months in prison, many governors had declared preaching Christianity to be punishable by as much as two years in prison.

Maximian had tolerated discrimination against Christians for years by praetorian prefects and governors for years, but had largely declined to participate himself. The turning point came on May 30, 314, when several Christians protested celebrations of the feast of Messalla. Since Messalla was regarded as the savior of the Roman Empire and the personification of all it stood for, Maximian interpreted the protest of ceremonies for worshiping Messalla as gestures of shameless contempt for the empire. Maximian soon assumed a positively anti-Christian stance.

In early June, Maximian wrote a letter to Diocles informing Diocles of his change of heart and asking Diocles what measures he thought were appropriate. Diocles, who was by that time preparing to retire, told Maximian that the appropriate model of anti-Christian policies had already been set up in many areas, and that Maximian would only need to adopt and build upon those policies.

The Great Persecution []

Although Christians had faced escalating discrimination from the state for years, the Great Persecution is considered to have begun on August 2, 314, when Maximian published the First Edict Against the Christians. This law officially set the minimum penalty for proselytizing Christianity at five years in prison, barred Christians from the army and all other state employment, deprived Christians of the right to petition courts or testify in court, made it illegal for Christians to assemble for worship (with violations punishable by no less than five years in prison), and called for the confiscation and destruction of copies of the Bible and other Christian texts. The edict also instructed the Caesar, praetorian prefects, governors, and other officials to take any actions beyond enforcing its provisions that they deemed necessary to repress Christianity.

As far-reaching as Maximian's edict was, progressively harsher policies were quickly adopted in many parts of the empire, including the Dominium Caesaris. Maxentius raised the minimum prison term for violating the edict to a life sentence, and governors of many provinces both inside and outside Maxentius' realm made violating the edict punishable by death. In February 315, Maxentius ordered the arrest of all Christian clergy within the Dominium Caesaris, and the governors of several provinces outside the Dominium Caesaris followed suit during the subsequent few months. In the summer of 315, provincial governors began subjecting Christians to higher taxes than other citizens owed, and this policy was officially adopted by Maxentius in October 315.

During 316, no additional anti-Christian legislation was enacted. Then in January 317, Maxentius offered amnesty to imprisoned Christian clergy, provided they offered sacrifices to the Roman deities. This offer was extended to Christians imprisoned for assembling for worship or proselytizing in March. Few Christians actually performed the sacrifices: most prisons in the Dominium Caesaris were overcrowded, so the wardens of many prisons simply used Maxentius' proclamation as an opportunity to release most or all of their Christian prisoners, and falsely recorded the sacrifices as having been performed. Finally, in August 317, Maxentius issued a law that all inhabitants of the Roman Empire were required to offer sacrifices to the Roman deities at least twice a year, with the punishment for refusing to do so being death. In January 318, Maximian issued the Second Edict Against the Christians, which made refusing to sacrifice to the Roman deities at least twice a year a capital crime. A year later, Maximian published the Third Edict Against the Christians, which made it illegal for non-Christians to protect Christians from arrest or for local authorities to falsely record required sacrifices as having been performed, with the minimum punishment for either action being ten years in prison.

Downfall[]

By 320, discontent with Maximian and Maxentius was growing. The consequences of their economic policies had been disastrous. For all the imperial propaganda claiming that Messalla was a god and that Maximian was a representative of the gods, few pagan Romans actually believed these things. The persecution of Christians had failed to wipe out Christianity or even significantly reduce the population of Christians in the empire (and majority of the small decrease in the Christian population that did occur was due to emigration by Christians who lived close to the imperial border). Also, the majority of the pagans did not support the persecution of Christians (which was in fact the reason for Maximian's third edict).

A turning point came on June 7, 320. Ovinius Gallicanus, the governor of the province of Dalmatia, announced that he had converted to Christianity, had refused to resign, and would henceforward refuse to enforce the empire's anti-Christian legislation. Word quickly spread. Four other governors joined Gallicanus in his defiance, and two duces announced that they would oppose any effort to remove the governors from power. On August 19, 320, these five governors and two duces met in Salona (OTL Solin). Four days later, they published the Declaration of Salona. In the declaration, they announced that they had formed a seven-member council called the Septumvirate. The Septumvirate announced its intent to depose Maximian and Maxentius and provisionally rule the Roman Empire upon overthrowing them. The members of this council agreed to end the imperial-level persecution of Christians and prohibit all local persecution, grant Christians equal rights under the law, and repeal the Edict on Acceptable Prices and the mandate for governors to institute economic planning.

Many army units quickly sided with the Septumvirate, and pro-Septumvirate militias were organized. Then in late September 320, Maximian launched an invasion of Septumvirate-held territory. Maximian and Maxentius rapidly lost territory to the Septumvirate due to defections, conquests, and popular uprisings. By June 321, Maximian and Maxentius began to ease their persecution of Christians in a desperate attempt to win back popular support; but their actions came too late and fell far short of the full equality that Christians had already been granted by the Septumvirate. On September 3, 321, Maximian's generals forced him to retire as pro-Septumvirate forces were rapidly taking control of central and northern Italy. By November 12, Thessalonica was surrounded; and Maxentius' generals killed Maxentius, surrendered to the Septumvirate, and then killed themselves.

The Septumvirate ruled the empire until December 12, 322, six days after appointing Valerius Maximus Basilius and Flavius Ablabius as the new Supreme Senator and Caesar, respectively. During their interim rule, they repealed many of the edicts issued by Maximian and Maxentius, recognized Christians as fully equal under the law, and separated the pagan priesthood from civil offices.

Retirement[]

After Maximian stepped down, soldiers in Genua quietly confined him in a small house for almost a month. He was escorted to Pisae (OTL Pisa) in October 321, where he was again confined in a small house for several weeks.

In November 321, one of the generals who had arranged for Maximian to retire quietly offered to allow him to settle near a village in Sardinia. The general would arrange for soldiers to protect him there, and would provide him with a pension for the rest of his life. In return, Maximian was to take a new name, tell no one about his former life, and avoid behaving conspicuously. Maximian accepted these conditions. He arrived in Sardinia in January 322.

During the regency of the Septumvirate, the Septumvirate ordered a search for Maximian with the intent of arresting him. Several months after Maximus Basilius became Supreme Senator of the Roman Empire, he ordered that the effort be abandoned.

Maximian found it difficult to adjust to his forced retirement, and his health began to decline in 324. In May 325, Maximian was found dead inside his house. Nobody involved in the effort to protect Maximian came forward until 328.