On the night of 12 April 1867, Benjamin Disraeli experienced his greatest political triumph, the passing of the 1867 Reform Act. Jubilant Tory MPs swept him out of the Palace of Westminster towards the Carlton Club on St James’s Street, where a crowd of supporters was waiting to toast his success. But as his parliamentary colleagues embarked on the serious business of drinking themselves into a stupor, Disraeli slipped away to a quiet white house on the edge of Hyde Park and to his wife Mary Anne. He arrived home to find her waiting with a late supper for him, consisting of a Fortnum & Mason raised pie and champagne. “He ate half the pie and drank all the champagne,” Mary Anne reported. “Then he said, ‘Why, my dear, you are more like a mistress than a wife.’”

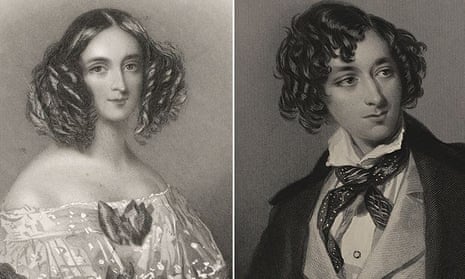

Benjamin and Mary Anne are figures around whom anecdotes coalesce: about what they wore, what they did and what they said. “My wife is a very clever woman,” ran one of Disraeli’s much-quoted sayings. “But she can never remember who came first, the Greeks or the Romans.” Mary Anne apparently told Queen Victoria that she always slept with her arms around Disraeli’s neck, and scandalised prim hostesses at country house breakfasts by discussing the beauty of her Dizzy – as she called him – in his bath.

When I first began working on their archive, I experienced the exhilarating sensation of tumbling down a rabbit hole into their world. Sitting in a freezing Oxford reading room, in which the heating never worked, I discovered in the 50,000 pieces of paper that Mary Anne collected the story of a rich and strange romance.

Their letters are themselves full of references to being cold, to the way in which the cold confines the body and chills the mind. At Stowe House, while waiting to meet the Queen, they shiver in draughty halls and inadequate evening garb. At Osborne, the Queen’s house on the Isle of Wight, Disraeli wears two greatcoats and a waistcoat inside as well as out. Mary Anne’s servants run back and forth from the House of Commons with warm clothes and boots to protect him from the chills of the debating chamber, until snow stops carriage wheels from turning and forces both master and mistress to stay inside.

Both the Disraelis loved drama and excitement, and they conjured their romance into being in a world thick with stories. In their youth they read versions of themselves in the epistolary novels of the late 18th century; in the 1820s and 30s they saw their aspirations reflected in the “silver-fork” novels (about high society) Disraeli and his literary contemporaries produced at great speed. They were middle-aged when the Victorian novel came to maturity in the 1850s; theirs was thus a great age of fiction, when the novel made a romance of reality and turned ordinary men and women, living ordinary lives, into heroes and heroines.

They tried to live as if they too were the hero and heroine of a grand romance. As an old lady resplendent in jewels and bright fabrics Mary Anne cast her history as a rags-to-riches fable, pretending to have worked in her youth as a milliner or, in her more creative moments, as a barefooted factory girl. Disraeli invented an illustrious ancestry for himself, featuring an ancient family who escaped from Spain to Venice, and then to England where, in his account, their ascent culminated in his own political success.

There was nothing very grand or heroic about the beginning of their romance. Mary Anne was 12 years older than Disraeli, very recently widowed when they embarked on their courtship. Her first marriage to an iron magnate had brought her wealth but not social acceptance. She was the undereducated daughter of a sailor and the combination of her background, rackety manners and distinctly unwidow-like behaviour meant that London’s smart society ladies kept their distance. At a party she was importuned by a drunken colonel who kissed her shoulder and then poured his drink over her; he was bundled out by his host, but the fracas was reported in the newspapers. Two gentlemen fought a duel over her after one of them made derogatory comments about her reputation. On visits to her first husband’s iron mines in South Wales she rode through the tunnels on a mine wagon, laughing all the way.

Even her friends were sometimes made uneasy by Mary Anne’s refusal to conform. When she held her first London ball she was so determined to outdo the hostesses who looked askance at her that she contrived a show-stopping table decoration: a windmill, complete with turning sails, perched above a stream in which swam gold and silver fish. At court and at other people’s parties her dresses were grander than the Queen’s, and she moved through the social season in a dazzle of diamonds.

Disraeli, meanwhile, was an adventurer, an outsider of Jewish descent who was overwhelmed by debt and facing ruin. In 1838, the year in which Mary Anne’s first husband died, the only thing preventing Disraeli’s immediate exile or incarceration in a debtors’ prison was the fact that, as an MP, he was immune from arrest. He lived in dread of parliament dissolving and his immunity evaporating with it.

Nor was he the only contender for the rich widow’s affections. Other “disreputables” (his word) gathered in her red and gold drawing room, hoping to win her hand and her money. But Mary Anne did not want to be married for her money, and she demanded that all her suitors woo her as if she were the heroine of a novel. Here Disraeli triumphed; the other disreputables didn’t stand a chance. His courtship of Mary Anne was tempestuous and extravagant, as together they manufactured emotions in order to paper over the cracks of an inauthentic, contingent relationship. They got up late, they wrote poems, they rowed and stormed out of rooms. “My nature demands,” he told her at one point, “that my life should be perpetual love.”

No one believed it. One of Disraeli’s friends called the match a comedy: onlookers dismissed him as a fortune hunter, and Mary Anne as a gullible fool. The fortune hunter and the fool were married on 28 August 1839 at St George’s, Hanover Square. Their papers for these years reveal how complicated their relationship had become, and that although theirs was not a romantic match, neither was it a straightforward marriage of convenience. The day before the wedding, Disraeli warned his money agent not to send letters about his debts in case Mary Anne read them, but he also wrote her a poem that suggests he had come to appreciate her spontaneity, sound judgment and a conversational style as surprising as it was quick. “I love her since her heart is true / And knows no guile ... / I love her wit that artless flows.” Writing from Tunbridge Wells where they spent the first night of their honeymoon, Mary Anne painted a picture for her new father-in-law: “We exemplify life’s finest tale – to eat – to drink – to sleep – love & be loved.”

In some respects they were a well-matched pair, and from the start they united over shared passions. Both of them loved the thrill of the campaign trail, and Mary Anne in particular understood the value of a solid election brand. During general election contests she would garland her person, her carriage and her husband with purple ribbons, before sallying forth to give kisses, hugs and cakes to the voters. Whenever she appeared, the crowds were won over by the enthusiasm and glamour she radiated. Sometimes the excitement even got the better of the Disraelis themselves. During a particularly successful campaigning visit to Edinburgh they were cheered to the rafters, and when they were alone they could not contain their glee. “We were so delighted with our reception,” Disraeli recalled, “that after we got back we actually danced a jig (or was it a hornpipe?) in our bedroom.”

The bustle of elections provided only an occasional distraction, though, and the day-to-day reality of married life proved rather more testing. Disraeli hid the full extent of his debts from Mary Anne for years, using a private post restante system to communicate with his creditors. His political career in the early 1840s was marked by disappointments and setbacks as he was forced to watch the promotion of less able men from the backbenches. Robert Peel and other Tory grandees distrusted him, and both the Disraelis felt the strain. Mary Anne marked passages of tension between them with a phrase that recurs in her account books from this time: “pas content”. There were fights, and periods of alienation, as well as continued sniping from a suspicious press. When Disraeli called Mary Anne a “perfect wife” in the dedication to his novel Sybil in 1845, in a gesture designed to fend off their detractors, one journalist mocked him for attempting to describe someone so evidently imperfect in such a way.

After they bought the estate of Hughenden in Buckinghamshire in 1848, the Disraelis found that their long-schemed-for house locked them together in mutual isolation each autumn. Mary Anne took refuge in her garden, planting and pruning by torchlight, transforming Hughenden into the romantic space of her dreams. Disraeli invented spurious reasons to return to the capital, begging trusted political friends to post fictive requests for his presence. Divorce was impossible and unthinkable, but neither of the Disraelis could reconcile their compromised reality with the romance they wanted. And so, slowly, together, they overcame their difficulties to make that romance a reality.

This, I think, is the magical thing about their story. Their union broke every rule of the Victorian marriage market: Mary Anne was older and much less well-educated than her husband, with none of the social influence that might have made up for such failings. Theirs was not a love match, and for years Disraeli consistently refused to share his financial plight and his innermost existence with his wife. But in spite of all this, a romance that had begun as a fantasy became, in its third act, authentic and true. “Dizzy married me for my money,” Mary Anne told the friends who came to while away the hours with an increasingly frail old lady. “But if he had the chance again, he would marry me for love.” After his ejection from office in 1868 Disraeli persuaded the Queen to give Mary Anne a peerage in her own right, and so the sailor’s daughter died Viscountess Beaconsfield. Within a week of her ennoblement Mary Anne had arranged for all the cushions at Hughenden to be embroidered with Bs, but she had also quietly organised a pension for a female acquaintance whose story had ended far less happily than her own. For the rest of her life she signed her letters to Disraeli “your devoted Beaconsfield”.

For his part, Disraeli came to realise that the love affairs of the old were just as unexpected and romantic as the amorous adventures of the young. “As for our enamoured sexagarians,” he wrote in 1870, “they avenge the theories of our cold-hearted youth.” So by the time of Mary Anne’s death in 1872, the Disraelis’ marriage was celebrated up and down the nation for the joy it brought husband and wife, and all who knew them. It was, thought the Times, “an essentially English union”.

The couple’s story is about luck, and the path not taken, and the transformative effects of a good match. My telling of it is founded on an extraordinary archive which encompasses letters, blackmail threats, suicide notes, account books, valentine cards, and even a box of hair: objects that chart a marriage that wrote itself into happiness. There is a hero and a heroine, elements of fairytale and poetry to be found in the everyday romance of ordinary and extraordinary lives. This, finally, was what struck the author of Mary Anne’s Times obituary as, in contemplating her history, he permitted himself a moment of reflection. “We are glad to believe,” he wrote of her marriage, “that the romance of real life often begins at the point where it invariably ends in fiction.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion