As beauty contests go, the battle between global heritage sites is fickle and fierce. For every Frick House in Manhattan, say, or Carss Cottage Museum in Sydney, there are faded former homes languishing unloved in forgotten corners of our cities. Too often the fate of important buildings is left to the vagaries of a rich person’s whim and the capricious decisions of local authorities.

Compare the indulgent treatment of the Royal Pavilion Estate in Brighton with the cruel attitude toward its neighbour Marlborough House on the Old Steine. In 1783, the Prince of Wales visited Brighton and stayed at Grove House – as Marlborough House was then known. Three years later, his agent in the town arranged a three-year lease on a lodging house. This would become, in fits and starts, the Royal Pavilion. Queen Victoria loathed the place and sold it to the local authority in 1850. She took most of the fixtures and fittings with her, but today thousands of people flock to its ersatz corridors in the belief that they are getting the genuine Regency article.

Marlborough House, a Grade I-listed house, was built more than 20 years before the prince came to town. It was unlucky with its owners. It was sold to the third Duke of Marlborough, then sold once more in 1786 to William Hamilton MP.

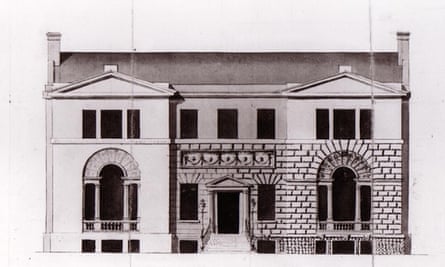

It was Hamilton who commissioned the Regency architectural go-to-guy Robert Adam to remodel the house in a style subsequently praised by the Pevsner Architectural Guide to Brighton and Hove as “a Palladian great house in miniature”. Hamilton died in 1796 and, in 1870, yet another owner, John Beal, leased the house to the Brighton School Board, which eventually bought it in 1891. It served as education offices until 1974 and then as a tourist information centre before being closed in the mid-1990s. The council sold the freehold of the property in 1999 to a businessman called Tony Antoniades for around £500,000.

In contrast, the Pavilion was kept out of the hands of private ownership lest its luminance be sullied. Last year, it was announced that the redevelopment of the estate would be boosted by £5m from the Heritage Lottery Fund. It has also received £5.8m from Arts Council England as the first phase of the £35m masterplan which the council boasted would see the Royal Pavilion Estate “preserved for generations to come”.

This shows what can be done when heritage bodies and the owners of historic houses share a common view of how the property ought to be maintained. But when there are conflicting views over what constructive conservation actually entails, the action that public bodies can take is limited.

Clare Charlesworth, principal adviser in the south-east office of Historic England, said: “Our hands are tied to some extent if a private owner cannot or will not maintain the building – we are an advisory body. We can help the council with an enforcement notice if the building is being damaged, but we can also help private owners if they are not sure how to conserve their property. We want to help them find sustainable new uses. That’s exactly what we are here to do.”

Antoniades, the current owner, however, has never moved into Marlborough House, which has been left to suffer the ravages of time, weather, and the occasional incursion of squatters. English Heritage placed the building on its “at risk” register. A game of cat and mouse ensued between the owner and the authority.

In a reply to a freedom of information request, Brighton and Hove City Council insisted that officers have “encouraged” Antoniades to repair the building and to bring it back into use. He has spent money on essential repairs but, like the Duke of Marlborough before him, it seems Antoniades quickly tired of his bauble. In December 2011 and January 2012 during site visits with potential purchasers to discuss alterations necessary for conversion to new uses, it was discovered the building was not fully weather-tight or secure.

The council asked Antoniades for an urgent meeting to discuss the issues, which was initially ignored, although a meeting was later held. Faced with a recalcitrant owner, the authority did the only thing it felt able to: it fired off a stream of letters. More correspondence took place between the council and the owner’s representative in April, May and June 2012 about the works required and a site meeting was held with the owner’s contractor. The scope of the works was subject to another flurry of letters in June, July and August 2012.

At no point did the council seek to compulsorily purchase the house and it said the works needed were satisfactorily completed by the end of November 2012.

With the owners’ permission, I took a look around the house last month. It was a desolate experience. Water has seeped through the roof, the original Adams fireplaces are long gone, destroyed in a fire in a north London warehouse, the suite of rooms on the ground floor, described as “exquisite” by Pevsner, are crammed with broken office furniture and tatty old files, and the walls are covered in graffiti left behind by squatters.

Last month, the city council approved plans drawn up by architectural firm Agora on behalf of Antoniades to return the house to a “luxury home”. The scheme includes a family room, TV room, kitchen, utility, plunge pool, sauna and wine cellar in the basement, with a drawing room, dining room, cloak room, gymnasium and music room on the ground floor. The first floor will feature a master bedroom with en suite and dressing room, five additional family or guest bedrooms, a bathroom and a gallery, while the second floor would accommodate staff and a games room. The public will not get a look in.

The decision has dismayed Nick Tyson, the honorary secretary at the Regency Town House, a conservation group, who worked with Antoniades to restore the front of the house in line with Robert Adams’s designs. The relationship, however, has soured.

“After the Royal Pavilion, this is the most important Regency building in the city,” Tyson says. “I was too late to stop the firm he hired from lopping chunks of the original Adams cement from the front of the building. The house has suffered a series of whopping errors with tragic consequences. It is trapped between a man with an ego and a council that doesn’t have the gumption to demand the work that is required.”

On the day the plans were approved, I met with Antoniades in the boardroom of his IT firm in Blenheim House, a few doors along the Old Steine from Marlborough House. He is a dapper man, with mental and physical agility that belie his 74 years. He told me that he disagreed with Nick Tyson’s verdict on the architectural ranking of the house – it is more important than that, he said.

“There is a lot of kidology about the Royal Pavilion. It’s a pile of crap. Marlborough House is the jewel in the crown of Brighton. I’m looking for a buyer, someone with the vision to rebuild Robert Adams’s dream on the Steine.”

It must be admitted that the building was in far from pristine shape when Antoniades took it off the council’s hands. He made it clear to me when I met him that he feels he has done his best in trying circumstances. “It needs an expert,” he said. “And that’s not me.”

But he is adamant that he will not be paying for the required improvements. “I’m too old for that,” he said. “I’m past my sell-by date.” We will have to wait to discover whether his unloved house is in the same situation.

Marlborough House is not alone in being regarded as a bauble by the monied and a nuisance by the local council. Historic houses, as emblematic of our identities and destinies as our own homes, deserve better. We must be more vigilant in safeguarding their future.

Follow Guardian Cities on Twitter and Facebook and join the discussion