The Only Person Who Knew Both Kennedy and His Killer

While in the Soviet Union, Priscilla Johnson McMillan met a young American in her hotel who was trying to defect. His name was Lee Harvey Oswald.

The 50th anniversary of John F. Kennedy’s assassination has drawn all manner of retrospectives. But for one woman, the memory of tuning in to the news coverage is particularly poignant. Priscilla Johnson McMillan is the only person who knew both President Kennedy and his killer.

McMillan worked for Kennedy on Capitol Hill in the mid-1950s, when he was a U.S. Senator, advising him on foreign policy matters. She then moved into journalism and in 1959 was stationed in the Soviet Union, reporting for The Progressive and the North American Newspaper Alliance. It was there that she met a 20-year-old American called Lee Harvey Oswald. He was staying in her hotel while trying to defect to the Soviet Union.

McMillan interviewed him. Oswald proceeded to critique the American system and informed her that he was a follower of Karl Marx. “I saw,” he said, explaining why he left the U.S., “that I would become either a worker exploited for capitalist profit or an exploiter or, since there are many in this category, I’d be one of the unemployed.” On that night in Moscow, Oswald also told McMillan that he had a life mission: “I want to give the people of the United States something to think about.”

Four years later, on the night of November 22, as McMillan followed news coverage of the assassination in Dallas from Cambridge, Massaschusetts, charges began to emerge that Oswald was responsible for shooting Kennedy. McMillan was astonished. “My God,” she said, “I know that boy!”

McMillan was a visiting scholar at Harvard’s Russian Research Center, but she quickly decided to write a book about Oswald and his young Russian wife, Marina. The work consumed her life. The research, reporting, and writing took more than a decade. The result, Marina and Lee, published in 1977, is a classic achievement in narrative reporting. The Atlantic praised the book as “extraordinary” and said that it “makes the necessary and subtle connection between private frailties and their power to change the history of the world.” The New York Times Book Review said it achieved what “the Warren Commission failed to do with its report.” Earlier this fall, Steerforth Press reissued Marina and Lee.

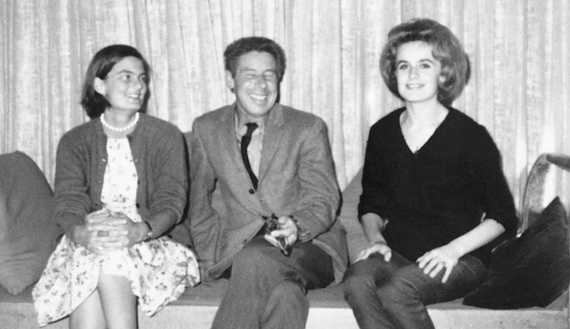

McMillan is now 85. I visited with her in recent weeks to discuss the individuals and atrocious incident that have animated so much of her life.

In Marina and Lee you write about recognizing Oswald when the press began to name him as the killer. That must have been the most shocking moment of your entire life.

It was. The night before the assassination, I mailed a letter to President Kennedy, in care of Evelyn Lincoln, Kennedy’s woman-of-all-work. I asked him to get Olga Ivinskaya, novelist Boris Pasternak’s lady friend, out of a labor camp in the Soviet Union. Later, I heard from Evelyn Lincoln saying that she’d never gotten the letter to him.

The film that Abraham Zapruder took of the Kennedy assassination has been running on TV as part of the retrospectives. What goes through your mind when you see it?

The first time I ever saw the shot that blew up Kennedy’s head was last week on the CNN documentary, The Assassination of President Kennedy. I’d seen the shot where Kennedy slumps, but never the other one where the explosion happens.

Did you think about the fact that you knew the man who fired that shot?

No. I thought more about the fact that I knew the man whose head was blown off.

How did you get a job working for Senator John F. Kennedy?

I graduated with a master’s degree in Russian studies from Harvard in 1953 and wanted to work on Capitol Hill. I went from office to office to see if there were any openings. I had a friend who worked for a Senator who informed me that Kennedy’s office was looking for someone new. But every time I went to Kennedy’s office the people there told me no. I kept looking. Finally, when I was at a party in New York, I got a phone call from his office. The person from his office asked, “Can you come to work on Monday?” So I said yes. But it was only for a very brief time. The subject I focused on was Indochina, for which I was in no way qualified.

Later, you visited Senator Kennedy in the hospital.

Yes, he was at the Hospital for Special Surgery, and he was having his back operated on. My brother-in-law worked there and he told me that the doctors found Kennedy to be most unusual. He’d be lying on his stomach while the doctors examined his back, and he was talking on the phone to people in New Hampshire asking about the latest political news. I had a roommate whose boyfriend also worked at that hospital and what I heard both indirectly from him and directly from my brother-in-law was that the real problem was that Kennedy had Addison’s Disease. The doctors didn’t think he could survive major surgery. They were trying to get his blood balanced so he could withstand the trauma.

Did you visit him more than once?

Yes, I went from time to time. I met his mother. I met Jackie. I met Jackie’s stepbrother, Hugh. Kennedy was very humorous. He was curious. He was always peppering me with questions – what I thought about politics, my personal life, anything.

You write, “One Saturday I found him with a Howdy Doody doll as tall as he was lying under the covers beside him.”

That’s right. At the foot of his bed there was a fish tank, too. There was a pile of books—many, many rows of them behind the head of his bed. And there was a Marilyn Monroe cutout upside down on the door of his hospital room. She was wearing white shorts and a blue mesh shirt. I don’t think he knew Marilyn Monroe at that point.

Were you in the Soviet Union when he was nominated?

I’d been kicked out in July 1960. I was in Bonn when he was nominated, listening on the radio.

Why did the Soviets kick you out?

They kicked out some tourists and diplomats—just a little bit of everybody—to show their displeasure at the U.S. sending over the U-2 aircraft to spy.

What was your biggest challenge in writing Marina and Lee?

Oswald did something that we all abhorred. I tried to explain it and be fair.

How soon after the assassination did you realize that you wanted to write a book about the Oswalds?

Maybe two or three months.

Marina Oswald was besieged with requests for interviews. How did you get her to cooperate with you?

My editor at Harper & Row, John Leggett, contacted Bill McKenzie, a Dallas attorney who was representing Marina. Mr. Leggett told Marina that I wished to write this book. Several months later Mr. Leggett heard back from Bill McKenzie saying, “Tell her to come down here.”

You met Marina in 1964, but your book wasn’t published until 1977. What took so long?

Well, it’s just the way I work. I guess I’m lazy. I was living in different places because I got married. I was very much into civil rights in Atlanta and the South. But mostly I just work slowly.

The original reviews that appeared when your book was published in 1977 are outstanding. One critic in The Age wrote, “The fruit of all McMillan’s devoted labor reads like a Dostoyevsky novel.” Author Thomas Mallon has praised what he calls your “propulsive storytelling skills” and says you’ve written the best book on the Kennedy assassination. When you started out, did you imagine this would be the result?

No, I didn’t. I hadn’t written a book before. I didn’t have much confidence. I’d just been a freelance newspaper reporter. But once I got into it, I wanted to make the book as good as I could. Marina was very loyal. She could have poked at me to hurry but she never did. When I had follow-up questions, she was always available. I could call her anytime. She never seemed to feel that I was an unpleasant intrusion.

The subtitle of your book is, The Tormented Love and Fatal Obsession Behind Lee Harvey Oswald’s Assassination of John F. Kennedy. What was Oswald so obsessed with?

Oswald was extremely anti-authoritarian. He had been a Marxist—as he called himself—from age 15. He’d done a number of things to express that view and his criticism of American life. He picked up a leaflet about the Rosenbergs when he was in school in the Bronx. When he went back to New Orleans, he always rode in the segregated parts of buses. He went into the Marines not because he was patriotic—but to get away from his mother. While there, he carried on his original interest in Marxism. He studied in the barracks, trying to learn Russian from a Berlitz book.

Why did he decide to go to the Soviet Union?

Because he thought it took care of everybody and preached democracy. When he got there, he found that the Soviet Union was a bureaucracy, just like the Marine Corps. So he came back to the U.S. When he returned, he had a very hard time making a living and supporting a small family. So he decided to try to bring down American capitalism.

That’s an audacious goal for one man.

That’s what he decided to try. First he shot at Gen. Edwin A. Walker, a leader of the John Birch Society and someone who’d been a very active segregationist. Oswald read about Walker in the newspapers he subscribed to, such as The Worker and The Militant. When the opportunity came to kill Kennedy, he wanted to hurt capitalism. I think if Oswald had lived and had a trial, that’s what he would have said. After shooting President Kennedy, he tried to reach John Abt, a lawyer for the American Communist Party, to defend him.

Do you know if the Kennedy family believes that Lee Harvey Oswald killed John F. Kennedy?

About ten years ago, I met Eunice Kennedy Shriver at a dinner party in Washington. She asked me, “Why did Oswald hate my brother so?” I replied, “He didn’t.” I said, “Oswald liked him. And he liked Jackie, too.” She said that she wanted to talk to me about it and she gave me her card. But of course I didn’t get back to her. And I’ve never discussed this subject with any other members of their family.

Your point is that while Oswald liked the President and Mrs. Kennedy, he viewed him as a symbol of American capitalism.

Exactly.

In your view, he would have wanted to assassinate any president, correct?

I think so. He probably wouldn’t have walked across Dallas if he hadn’t had a job directly over the presidential parade route. When Oswald was presented with the target, he thought he was fated to do it.

How damaging was the Kennedy assassination to the Communist Party?

I don’t know if people have linked Oswald to the Communist Party. He certainly wasn’t a member.

Do you regard Lee Harvey Oswald as a Marxist?

He was a self-proclaimed Marxist. But he wasn’t a good Marxist in that Marxists don’t believe in individual violence. They think history is made by big, broad national movements and not by individuals.

A lot of people are still intrigued by conspiracy theories, particularly the allegation that the C.I.A. was behind the assassination. Where would that have come from? Was it something Communists in the States might have encouraged, rather than having the story be that the president was killed by a Marxist?

My impression is that the American Communist Party kept as low a profile as it could. The people in it were genuinely embarrassed. They had letters from Oswald, and so did the Socialist Workers’ Party and the Fair Play for Cuba people. They were all extremely embarrassed by that correspondence. They had been no more than polite respondents to him. They didn’t want to touch him. They saw that he was a nut and didn’t want to have anything to do with him.

When Marina and Lee was published in 1977, it went against the conspiracy theory trend. There was even a Congressional committee at that time which concluded there was likely a conspiracy. How was it to swim against that tide?

I had an office above a hamburger stand in Harvard Square and when I would go down to eat lunch, I would hear students talking conspiracy. I went back up to my office and put together my Grecian vase of Oswald. When Marina and Lee was published, my husband told me that people were going to bookstores and telling them that I was a C.I.A. spy and not to carry the book. In 1995, when Norman Mailer came to Cambridge with his book Oswald’s Tale, somebody in the audience stood up and said that my husband and I were both spies for the C.I.A. and F.B.I. Many of our neighbors were there. They seemed quite surprised. There’s a lot of stuff like that online.

So, for the record, since you bring up these accusations: Have you ever been associated with the C.I.A.?

No, I haven’t.

What do you make of the shooting of Oswald by Jack Ruby?

Pretty much what came out at his murder trial. Ruby was so upset by the assassination that when he got an opportunity to kill Oswald on Sunday, he took it. Originally, he had been in that police and courts building on the night of November 22. He had access because as a nightclub owner, he knew all the policemen. They let him in. On the morning of November 24, he had his dog and his gun with him when he drove to Western Union to send money to one of his dancers who couldn’t pay her rent. There was a long line there, and he waited longer than expected. He’d left his dog, by the way, in the car. Meanwhile, Oswald was being questioned on an upper floor of the police and courts building. They had planned to move him during the night to avoid the press, but they didn’t in order to accommodate the press. Dallas was like a small town back then. For instance, the postal inspector, Harry Holmes, went by to see the police captain called Will Fritz. They were friends. Fritz told him, “Oswald’s right here. Don’t you want to talk to him?” So Holmes testified that he talked to Oswald for a while. Anyway, it was time for Oswald to come out. He was late, and Jack Ruby was late coming from Western Union. They were both off-schedule, and Ruby had the opportunity.

You lived in the Dallas area when you were researching Marina and Lee. How did the city strike you?

My experience was very good. Marina and I would go to the grocery store. She would look at the movie magazines while I was getting groceries. If people talked to her at all they were nice. Otherwise, they ignored her.

Do you think many people recognized her?

I think so. It was a very small place. She was in Richardson, Texas, then. There was an older couple, Dick and Cora Smith, who took her under their wing and treated her like a child. There were the Russians who had known the Oswalds before the assassination—they were very edgy but nice. There was a community of ballet dancers, and they were very nice. One guy who was in the ballet community loaned us an A-frame house on Lake Texoma to work in. Very early on in my research, I was on a plane flying down there. The man who was sitting next to me in tourist class asked why I was going to Texas and I told him. He then introduced himself as Stanley Marcus. He said if Marina and I ever needed help, he would be there.

The president of Neiman Marcus.

Can you imagine?

In the 1960s, Marina Oswald said that her husband was guilty of killing President Kennedy. Now, she seems to be a conspiracist. The Daily Mail newspaper in the U.K. recently reported that Marina “believes that the truth of Kennedy’s murder has been hidden by a cover-up” and that Oswald was “set up to take the fall for the C.I.A. and Mafia.” How do you account for her change?

I am not certain, but think Marina’s change of views may stem from her daughters’ reluctance to accept their father as the assassin and possibly also from the influence of a group of conspiracy theorists in Dallas in the 1980’s.

When was the last time you were in communication with Marina Oswald?

1982.

In the Foreword to the new edition of your book, novelist Joseph Finder writes that you shared two-thirds of your book advance with Marina. Does she receive any proceeds from this new edition?

Marina received royalties for the 1977 edition but not from this new edition.

As someone who lived in the Soviet Union and spent decades researching and writing about the Cold War, did it surprise you when Soviet communism collapsed in 1991?

I certainly didn’t think it would happen. You wonder what all of us were doing spending our lives studying the Soviet Union if we didn’t guess any better than that.

Did Hollywood express any interest in trying to make Marina and Lee into a film?

Yes. A producer called Lester Cowan came to see me before I even wrote it. He told me what should be in the book. I didn’t know anything about the movies. But I thought, Gosh, I don’t know what’s going to be in my book, how can he tell me what to put in it?

Speaking of the movies, did you see Oliver Stone’s JFK?

No—I just didn’t want to.

Did you have any contact with Oliver Stone?

His cameraman called me during filming. I didn’t know him, and I don’t know how he knew my telephone number. He said that he was all covered with mud and slime because he’d been shooting from a swamp the night before – that they’d been up all night long. He told me, “I’ll do anything for Oliver, but you should know that he’s making it up as he goes along.” Also, a female newspaper reporter called to inform me that she was going to play me in JFK. She also wanted to know if I would talk to her so she could play me better. So I wrote to Stone—or I had my lawyer write to him—to say that I forbade him from representing my person in any way. I didn’t actually have a leg to stand on, though. He could have done anything he liked, but he didn’t.

The cover of the new edition of Marina and Lee is different from the 1977 cover. It features an arresting photo of the Oswalds.

I hate it. I know the circumstances in which the photo was taken. It was November 22, 1962. They were squashed into a photo booth at a Greyhound Bus station in Dallas on their way to Thanksgiving with Robert Oswald in Ft. Worth. I’m sick of their faces.