On Saturday 8 January 1927, in the late afternoon, my grandfather noticed a young woman through the window of the Galeries Lafayette in Paris. He waited until she came out, then greeted her with a big smile. “Mademoiselle, you have an interesting face. I would like to paint your portrait.” He added: “I’m sure we shall do great things together. I’m Picasso,” pointing, by way of introduction, at a large book about himself. “I would like to see you again. I’ll meet you at 11 o’clock on Monday in Saint-Lazare Métro station.” Marie-Thérèse Walter, my future grandmother, had just met the love of her life. And Picasso had been reborn.

She had not the slightest idea who this Picasso might be, and the book was in Japanese, but she noticed his superb red and black tie – which she would afterwards keep all her life: “In the old days, young women didn’t read the papers. Picasso meant nothing to me. It was his tie that interested me. Besides, I found him charming.” Marie-Thérèse kept the appointment. “I turned up just like that, by chance, because he had a lovely smile,” she would later recall. “He took me to a cafe, then to lunch, and then to his studio; he looked at me, he looked at my profile, he looked at my face, and then I left. He told me: ‘Come back tomorrow.’”

After that, it was always tomorrow. They started a conversation which was renewed every day. He told her that she had “saved his life”, which Marie-Thérèse scarcely understood. Pablo was going back to his conjugal home in the Rue La Boétie every evening. His wife, Olga, asked no questions, although her husband’s absences were increasingly frequent and he returned late at night. As long as he came back, honour was satisfied.

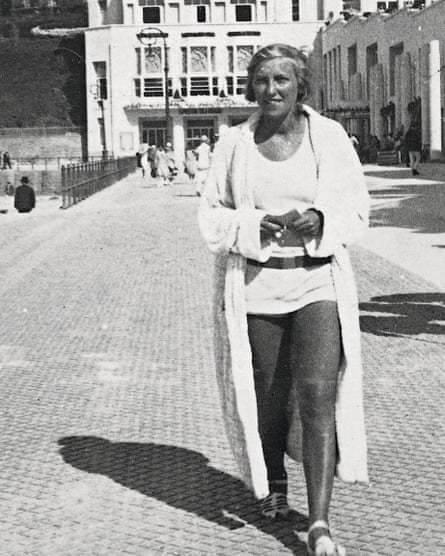

Meanwhile, he drew Marie-Thérèse frenziedly. Superb drawings, though still anonymous. He became a young lover again. My grandmother was athletic, which was unusual at that time. She rowed, cycled and did gymnastics; later, she would ride regularly, and then go climbing in Chamonix. She was fresh and spontaneous; not shy, but reserved; well brought up, but not “educated” like the young women who, in those days, used to be trained in their social duties.

“My life with him was always secret,” Marie-Thérèse said. “Calm and peaceful. We said nothing to anyone. We were happy like that, and we did not ask anything more.” The artist could devote himself to his art. This “Marie-Thérèse period” generated drawings and engravings of exceptional force, both in their subjects and in terms of the emotions that inspired them. In 1928, Picasso returned to sculpture, which he had given up in 1914. The desire to work with solid matter had been reawakened and he found nourishment for this creative experiment in Marie-Thérèse’s sturdy curves and the oval of her face.

In May 1930, he bought the Château de Boisgeloup, in Gisors, near Paris, for the potential workspaces he saw in its stables and outbuildings. He was now in a position to devote himself to monumental sculpture and painting by turns, and to explore all their possible interrelations. This would give rise to busts, imposing heads of women and a series of portraits that Marie-Thérèse illuminates with her blond hair – it includes The Dream, which is now on show in the UK for the first time at Tate Modern.

In the autumn of 1931, Picasso plunged himself into feverish preparations for a big exhibition the following year, which he expected would bring him well-deserved recognition and allow him to get even with his friend Matisse, now at the height of his glory. That retrospective in 1932 was, in fact, Picasso’s most important ever. The artist assembled canvases from all his “periods” right up to the latest portraits of Marie-Thérèse that he had not yet shown to anyone. Leading collectors lent works without hesitation. It was the cultural event of the season in Paris, although Picasso did not attend the opening.

The early summer of 1932 was spent at his studio in Boisgeloup with Olga and their son, Paulo, avoiding the traditional seasonal migration to the Côte d’Azur, so that Pablo could continue to work. In the summer of 1933, the family went to Cannes, and then to Barcelona. But the storm was brewing. Pablo got Marie-Thérèse to come in secret and installed her in a nearby hotel. And once back in Paris, he started, for the first time, to investigate the possibility of divorce, consulting a leading Parisian lawyer as divorce was now permitted by the recently established Spanish Republic. “And then one day I found I was pregnant,” Marie-Thérèse would later recount. “He fell on his knees, wept and told me it was the greatest happiness of his life.”

Picasso initiated the divorce proceedings, thinking they would be as quick as getting married. But Olga didn’t want to be a divorced woman in Paris high society. She moved into a hotel and started an adamant resistance that would last eight years. In the end, civil war in Spain brought Franco to power. He abolished divorce in 1939, so the Paris tribunal could only declare a legal separation. Olga remained “Madame Picasso” until her death in 1955 and Pablo could not marry Marie-Thérèse.

My mother, Maya, was born on 5 September 1935, in Boulogne-Billancourt. Marie-Thérèse had given birth under general anaesthetic – a dangerous medical fashion of the time – and so felt and remembered nothing of the delivery, and there were complications: Maya did not move when she was born. Frightened, Picasso had carried out an emergency baptism, throwing water over the lifeless little body as a priest would have done, to administer the first and last rites. And Maya came back to life!

In the register of births, she appears as María de la Concepción, in memory of her father’s sister, who had died. María very soon became Maya. For my grandfather, who was 54, life with Marie-Thérèse and Maya was a rejuvenation. His tenderness for little Maya was reflected in his canvases as much as in his poems and letters. While Maya was a small child, he kept a kind of diary in his sketchbooks, describing the little girl’s metamorphoses. Their pages display a succession of astonishing closeups, in which Picasso tries to seize instants in a life that grows, elusive and changeable, from one second to another. We see her in her sleep, sucking her thumb, dreaming, or roaring with laughter.

When war was suddenly declared, in September 1939, Marie-Thérèse and Maya were on holiday in Royan, north of Bordeaux, and stayed there until the spring of 1941. Picasso concealed from Marie-Thérèse the existence of Dora Maar, a photographer and his mistress since the summer of 1936. He arranged for my grandmother and their daughter to return to Paris, to a flat on Île Saint-Louis. My grandparents’ relationship had now lasted 14 years. Nevertheless, Marie-Thérèse was perceptive. Pablo could not lie to her about the new state of affairs. She was now aware of the details of his love life: she knew that she had to share him. Maya was brought up believing “the fiction that her father worked a long way away”, as his subsequent lover the painter and critic Françoise Gilot would explain later.

Growing up with my brother, Richard, and sister, Diana, we discovered quite naturally, looking at the walls of our home, that Pablo Picasso was our grandfather. My school friends had family photos. I had family portraits: my mother as a child, my grandmother looking pensive. But we were still too small to ask questions or to wonder about these grandparents who never came to see us. Picasso was someone who people talked to me about occasionally, but whom I never saw.

My grandfather only began to come to life for me the day he died, 8 April 1973. It was a Sunday afternoon, and after lunch we were watching a film on television. At the end, there was a special newsflash. I knew what that meant: some sort of disaster, a terrorist attack, the death of some famous person. There was no picture, but an unemotional voice intoned: “The painter Pablo Picasso passed away this morning at his home on the Côte d’Azur. He was 92. He was generally held to be the artist who invented 20th-century art.” At school, I became an object of curiosity. Picasso’s grandson! But life went on and Picasso became an institution.

On 20 October 1977 my mother woke me and told me that Marie-Thérèse, my grandmother, had died. At first I thought she meant my father’s mother. “No, it’s Baba, my mother” (Baba was the nickname I gave her) and she couldn’t hold back her tears. Shortly afterwards, I saw Maya set off in the car for Juan-les-Pins, near Antibes, where Baba lived. My father, Pierre Widmaier, thinking I was old enough to understand, then told me that Marie-Thérèse had killed herself.

Marie-Thérèse and Pablo had talked again on the telephone only a week before he died, four years earlier, in 1973. She had noticed that he was not well and had warned Maya, her feeling confirmed by the very feeble handwriting of Pablo’s last letter, which had arrived on the morning of the telephone call. With his death their bond was finally broken.

- Picasso: An Intimate Portrait by Olivier Widmaier Picasso is published by Tate. The EY Exhibition Picasso 1932 – Love, Fame, Tragedy is at Tate Modern, London SW1. tate.org.uk.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion