By Diana Crumpler

Abstract

In 1966, Dr. Ida Macalpine and Dr. Richard Hunter demonstrated that the many health problems of George III were compatible with a diagnosis of porphyria. The porphyrias are a group of hereditary multi-system disorders involving abnormalities of porphyrin metabolism. They traced the disease through eight generations back to Mary, Queen of Scots, but made no attempt to delve further into the origins of the faulty gene. My hypothesis is that it was Margaret Tudor, sister of Henry VIII and wife of James IV of Scotland, who brought porphyria to the Royal House of Stuart. To this end, I have traced what appears to be a similar disorder back a further nine generations, through the French Houses of Valois and Bourbon.

Introduction

Porphyrins are cyclic tetrapyrole derivatives, found in all cells and fundamental to pigments such as hemoglobin. Porphyria involves a disturbance of the metabolism of porphyrins, sited either in the bone marrow (erythropoietic porphyria, caused by a recessive gene) or the liver (hepatic porphyria, caused by a dominant gene). Also known as Günther’s disease,erythropoietic porphyria is hallmarked by unsightly pigmented scarring, hirsuteness and red-tinged teeth; it has been proposed as the origin of the werewolf legend.1 The porphyrias highlighted in the following article are of the hepatic kind. My usual field of interest is multiple chemical sensitivity (MCS).2-4 My interest in porphyria was sparked in 1994 when it was demonstrated that MCS and the related CFS (chronic fatigue syndrome) also involved a disorder of porphyrin metabolism.5,6 It is now believed that this acquired porphyrinopathy is the upshot of interaction between nitric oxide and peroxynitrite and the regulatory mechanism governing the synthesis of porphyrin biosynthetic enzymes, both syndromes being underpinned by a vicious cycle predicated upon elevated nitric oxide and peroxynitrite (the NO/ONOO־ cycle).7

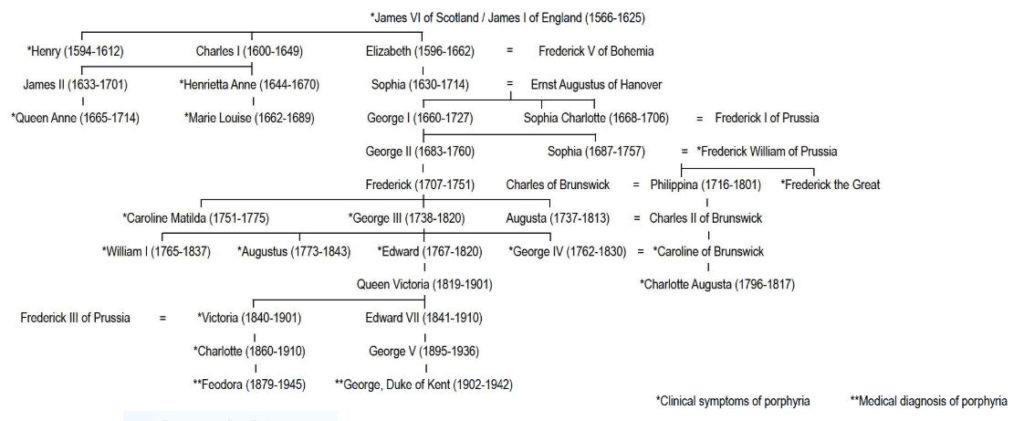

In 1966, mother-and-son medical sleuths Dr. Ida Macalpine and Dr. Richard Hunter solved a two-centuries-old mystery. George III’s numerous health problems, both physical and mental, were compatible with a diagnosis of porphyria. Sifting assiduously through archives, they traced the disease through eight generations back to Mary, Queen of Scots.8 Thirty years later, Rohl, Warren, and Hunt extended the descent of porphyria to the Duke of Kent, who died in a plane crash in 1942. They also speculated that Queen Victoria and Princess Margaret may have been affected.9

Rather than a single disease, the porphyrias are a group of related hereditary enzyme deficiency disorders involving the central, peripheral, and/or autonomic nervous systems. All involve abnormalities of porphyrin metabolism due to deficient enzyme activity; the type of porphyria depends on the specific defective enzyme (the affliction of the Royal Houses of Stuart and Hanover is now believed to have been variegate porphyria). As naturally occurring pigments, porphyrins are basic to life and all normal beings excrete small quantities. But if the processes governing porphyrin production and metabolism are disrupted, excess porphyrins may accumulate in organs and tissues, where they can produce toxic effects: the deposition of porphyrins in the skin, for instance, may result in acute sunlight sensitivity. In other words, a metabolic glitch allows porphyrins to accumulate to the point where they become toxic.

Symptoms may include acute abdominal pain, behavioral changes ranging from depression to frank psychosis, bowel and bladder problems, fatigue, fluctuations in blood pressure, menstrual exacerbation of symptoms, photosensitivity and skin lesions, paralysis (may be temporary and partial), fever, nausea, difficulty swallowing, headaches, paraesthesias, profuse sweating, tachycardia, and chest pain.

“Mary, Queen of Scots is one of the great invalids of history, not only the great tragic figure,” commented Macalpine and Hunter. “So notorious were her colics that her son [James VI] who never lived with her knew of them and recognised his own affliction in hers.” Royal physician Sir Theodore Turquet de Mayerne’s meticulous record of James’ symptoms – frequent bouts of colic, diarrhea, vomiting, palpitations, fast and irregular pulse, difficulty swallowing, rashes and skin lesions, pain and weakness in the limbs, bouts of melancholy, fits of unconsciousness, convulsions, and “water red like Alicante wine” – also allowed for a hindsight diagnosis of porphyria.10 The latter was the clincher. Porphyrins, complexed with metals, are responsible for many of the brilliant colors of Nature, and the term porphyria (derived from porphyra, Greek for purple) refers to the discolored urine that may be present during an acute attack.

Mayerne’s notes also enabled Macalpine and Hunter to identify porphyria as the cause of death for James’ son, Henry, Prince of Wales. Henry died suddenly on 6 November 1612 at St James’s Palace. He was only 18 and his death so violent and so sudden that poisoning was suspected. An energetic youth, fond of sport, and “of a good constitution,” Henry had been stricken with acute abdominal pain and diarrhea, violent headaches, a rapid pulse, weakness, and buzzing in his ears. His breathing became labored, then came delirium (“alienation of braine, ravynge & idle speech out of purpose”), convulsions, and coma.10 Henry had been buried with his grandmother, Mary, Queen of Scots, in Westminster Abbey. Three years later his cousin and friend, Arbella Stuart, was laid to rest in the same tomb. All three occupants had, during their tragic lifetimes, suffered from the same agonising and baffling symptoms.11

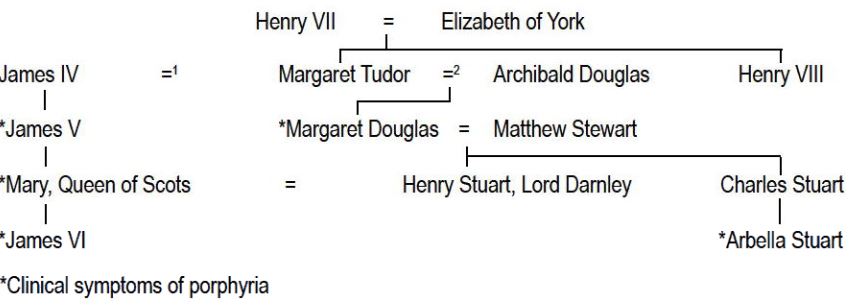

Macalpine and Hunter did not attempt to trace the origins of porphyria any further than Mary, Queen of Scots. The incidence of porphyria being relatively high among the Scots, Irish, and Scandinavians, the popular assumption appears to be that it was transmitted through the Stuarts, and Mary’s father, James V, did indeed exhibit symptoms of the disorder. If, however, we factor the ancestry of Arbella Stuart into the equation it becomes apparent that the aberrant gene may have other origins (see Table 1).

Arbella, too, was severely afflicted, albeit with a greater tendency towards bouts of mental instability (Arbella had a better claim than James to the English throne, and except for this complication would most likely have been Elizabeth’s successor.*) It is not, however, a Stuart but Margaret Tudor, a sister to Henry VIII, that would appear to have been the ancestor-in-common who brought porphyria to the House of Stuart. Margaret had been married at the age of twelve to James IV of Scotland. After James IV was killed in battle in 1513, Margaret married Archibald Douglas, Earl of Angus; James VI was Margaret’s great-grandson from her first marriage; Arbella, her great-granddaughter from the second marriage.

* Porphyria has more than once determined the course of English history. Had Henry Stuart not succumbed to the disease in 1612, his younger brother of a different nature would not have come to the throne as Charles I. Had Princess Charlotte Augusta not died of an acute attack brought on by childbirth in 1817, there would have been no Victorian era – indeed, Victoria herself would not have been conceived as Charlotte’s elderly uncles discarded their mistresses and took young brides of royal pedigree in the race to produce an heir to fill the succession vacuum created by Charlotte’s death.

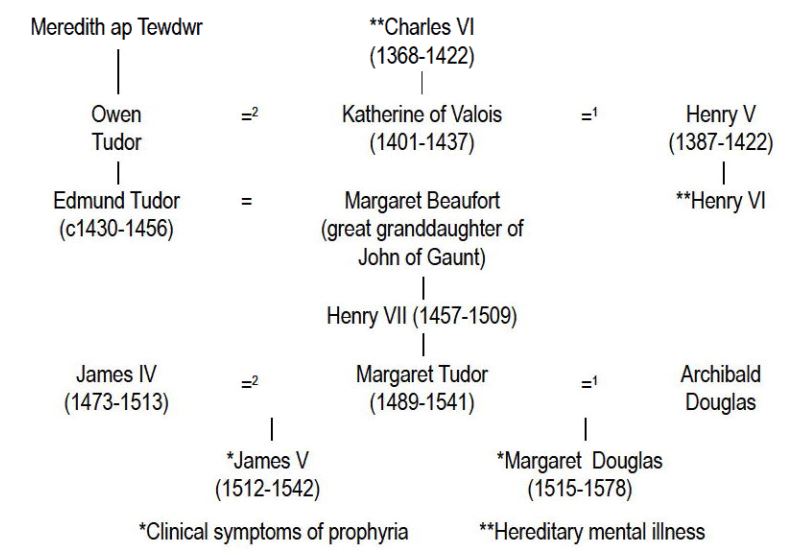

How, then, could porphyria have infiltrated the House of Tudor? For a possible answer, we need firstly a nutshell history of the dynasty’s rise to power. Henry V (1387-1422) was England’s last great Plantagenet monarch. Charismatic and capable, he not only won back England’s continental possessions lost by John but was named as successor to Charles VI, the French king. To seal this agreement, Henry was married to Charles’ daughter, Katherine of Valois. Their son, Henry VI, was an infant of just eight months when Henry died on campaign in France in 1422. When young Henry came of age, he proved a weak and ineffectual ruler; like Charles VI, he was also subject to bouts of insanity. By 1450, the country was in a bad way: the king’s advisors were corrupt; finances were chaotic; people marched on London in protest; and the French territories were again lost.

The upshot of this state of affairs was the civil war later dubbed the Wars of the Roses as Yorkist (white rose emblem) and Lancastrian (red rose) factions battled for supremacy. Both contenders were descendants of Edward III, the Yorkists through Edmund, Duke of York; Henry and the Lancastrians through John of Gaunt and Blanche of Lancaster. The Yorkists were ultimately triumphant and Edmund’s great-grandson was crowned Edward IV in 1461. But still peace and stability proved ephemeral. Although Edward had been succeeded by his 12-year-old son Edward V, his brother, Richard of Gloucester, had Edward and his younger brother declared illegitimate and himself proclaimed king. Consigned to the Tower of London, the two little princes were never seen again.

Richard ruled by tyranny, and once again people looked to the House of Lancaster for salvation. But who was left of John of Gaunt’s line? Henry VI had been murdered after his deposition and Edward, his only son, had been killed in 1471 at the Battle of Tewkesbury. The only suitable contender was Henry Tudor, John’s great-great-grandson from his third marriage to Katherine Swynford. The forces of Henry Tudor and Richard III clashed at Bosworth Field on 22 August 1485. Richard was slain and there, on the battlefield, Henry proclaimed king. The Wars of the Roses were ended, and with them three centuries of Plantagenet rule. The House of Tudor now ruled England.

After Henry V’s death, Katherine of Valois had either secretly married or formed a liaison with Owen Tudor, a Welsh squire descended from the olden princes of an independent Wales. History records as indisputable the fact that Katherine transmitted her father’s mental illness to her son by Henry V. My hypothesis is that that illness was porphyria, and that it was also transmitted to her Tudor descendants (see Table 2).

The reign of Katherine’s father, Charles VI, had started well. Governing wisely after a self-serving regency, he was soon known as Charles the Beloved. By the end of a reign blighted by bouts of psychosis, the sobriquet had become Charles the Mad. His first recorded attack occurred in 1392, when he was 24. From the start of a military campaign, Charles had appeared feverish, impatient, and rambling. One hot afternoon, as the army rested in a forest, a drowsy page dropped the king’s lance. The noise as it clanged against a metal helmet sent Charles into a frenzy; by the time his chamberlain and soldiers were able to subdue him, several men lay dead. Charles then fell into a coma.

Later bouts left him at various times not knowing his name and unaware that he was king; unable to recognise his wife and children; claiming to be St. George; refusing to bathe or change his clothes; and running wildly through his palace. Pope Pius II recorded that one of Charles’ delusions involved the belief that he was made of glass and would shatter if touched; to protect himself he had iron rods sewn into his clothes.

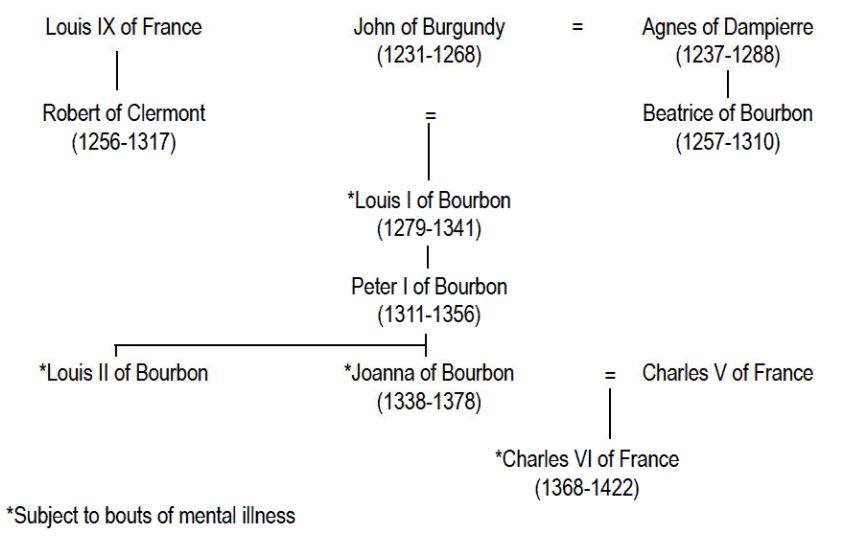

“It didn’t come from my side of the family,” Charles’ supremely capable father could well have said. Where, then, did it originate? With the Bourbons, his mother’s people. The French House of Bourbon was founded in 1272 when Robert of Clermont, a younger son of Louis IX, married Beatrice of Bourbon. The daughter of John of Burgundy, Beatrice was heiress to the Bourbon estates through her mother, Agnes of Dampierre. Louis, Robert and Beatrice’s eldest son, was then created the first Duke of Bourbon. (see Table 3)

Louis’ legacy was, however, a blighted one. From some ancestor whose identity is now obscured by the mists of time, Louis had inherited mental illness, a trait that was transmitted to his grandson, Louis II (one of the incompetent regents during the minority of Charles VI); his granddaughter, Joanna of Bourbon; his great-grandson, Charles VI of France; his x 3 great-grandson, Henry VI of England and, if the Bourbon malady was indeed porphyria, through the Tudors and Stuarts to George III and beyond to the twentieth century. The chroniclers do not record whether the Bourbons also exhibited physical symptoms compatible with porphyria. Perhaps they did, but only the more dramatic, more politically disastrous mental manifestations were then considered worthy of mention; a colicky king does not pose the same threat to national stability as one periodically insane. Moreover, by Stuart times the zeitgeist had changed: de Mayerne was a medical man moved by the Renaissance spirit of scientific enquiry.

To return to the Tudors. If Margaret Tudor was the progenitor of porphyria in the House of Stuart, did she herself exhibit any symptoms of the disease? Of Margaret’s medical history, we know only the cause of death: “palsy,” a term not incompatible with porphyria. Margaret is reported to have “had a palsy on Friday and died the following Tuesday.” That, believing she would recover, she failed to make a will suggests that she may have already suffered and survived similar attacks.

Of her daughter’s health, we know more. Fourteen years before her death in 1578, Margaret Douglas had described to William Cecil symptoms of an affliction similar to that suffered by James V, Mary Queen of Scots, James VI, Prince Henry, and Arbella Stuart. In this letter “she acknowledges as constitutional the same malady which subsequently proved fatal to her, thus exonerating any accounts of poisoning her.”12 Margaret’s precautions notwithstanding, Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, was later rumored to have poisoned her. In effect, Henry and Margaret were undoubtedly poisoned, not by political conspirators but by toxins produced within their own bodies.

Was Margaret Tudor’s brother, Henry VIII, also affected? Food for thought perhaps.

References

- Illis L. On porphyria and the aetiology of werewolves. Proceedings of Royal Society of Medicine. 1964; 57(1): 23-26.

- Crumpler D. Chemical Crisis. Newham: Scribe: 1994.

- Crumpler D. Prostituting Science: the Psychologisation of MCS, CFS and EHS for Political Gain. Maryborough: Inkling Australia: 2014.

- Crumpler D. MCS and EHS: An Australian perspective. Ecopsychology. 2017; 9(2): 112-116.

- Downey D. Fatigue syndrome revisited: the possible role of porphyrins. Medical Hypotheses. 1994; 42: 285-290.

- Downey D. Porphyria: a new perspective. Medical Hypotheses. 1996; 46: 378-382.

- Pall M L. NMDA sensitization and stimulation by peroxynitrite, nitric oxide, and organic solvents as the mechanism of chemical sensitivity in multiple chemical sensitivity. FASEB Journal. 2002; 16: 1407-1417.

- Macalpine I, Hunter R. The ‘insanity’ of King George III: a classic case of porphyria. British Medical Journal. 8 Jan 1966, pp 65-70.

- Rohl J, Warren M, Hunt D. Purple Secret. London: Bantam Books: 1998.

- Macalpine I, Hunter R, Rimington C. Porphyria in the Royal Houses of Stuart, Hanover and Prussia: a follow-up study of George III’s illness. British Medical Journal. 6 Jan 1968, pp 7-18.

- Norrington R. In the Shadow of the Throne. London: Peter Owen: 2002.

- Strickland A. Lives of the Queens of Scotland and English Princesses. Vol 2, 1851, p 447. Quoted in In the Shadow of the Throne, p 30.