Malta Story

| Malta Story | |

|---|---|

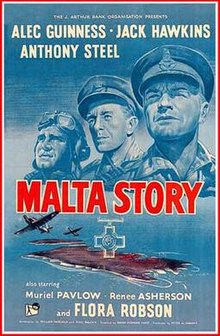

Original UK film poster | |

| Directed by | Brian Desmond Hurst |

| Written by | Nigel Balchin William Fairchild |

| Based on | Story by William Fairchild an idea by Thorold Dickinson Peter de Sarigny Sir Hugh P. Lloyd (book, Briefed to Attack) |

| Produced by | Peter De Sarigny |

| Starring | Alec Guinness Jack Hawkins Anthony Steel Muriel Pavlow Flora Robson |

| Cinematography | Robert Krasker |

| Edited by | Michael Gordon |

| Music by | William Alwyn |

Production company | Theta Film Productions[1] |

| Distributed by | GFD (UK) United Artists (US) |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 103 minutes (UK) 97 minutes (US) |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

Malta Story is a 1953 British war film, directed by Brian Desmond Hurst, which is set during the air defence of Malta during the Siege of Malta in the Second World War.[2] The film uses real and unique footage of the locations at which the battles were fought and includes a love story between a RAF reconnaissance pilot and a Maltese woman, as well as the anticipated execution of her brother, caught as an Italian spy. The pilot is loosely based on Adrian Warburton; the Maltese woman's brother is based on Carmelo Borg Pisani, who was executed in 1942.

Plot[edit]

In 1942 Britain is desperately holding onto Malta. Invasion seems imminent; the Italians and Germans are regularly bombing the airfields and towns. Flight Lieutenant Peter Ross, an archaeologist in civilian life, is on his way to an RAF posting in Egypt, but is stranded when the Lockheed Hudson on which he was a passenger is bombed while attempting to refuel on Malta. Air Commodore Frank, having just lost a photo reconnaissance pilot, has Ross reassigned to him, as that is Ross's speciality.

Peter meets Maria, a young Maltese woman working in the RAF operations room. The two fall in love and spend a few romantic hours at the Neolithic temples of Mnajdra and Ħaġar Qim. In the meantime, the situation at Malta becomes desperate. Famine looms, as relief convoys fall prey to Axis aircraft. A crucial convoy is severely mauled by day and night aerial attacks, but enough ships, including the vital oil tanker SS Ohio, reach Malta.

Peter proposes marriage to Maria, although they realise that wartime is not favourable to lasting love affairs, as Maria's mother suggests; nevertheless, the young couple remain hopeful of the future. Maria's brother Giuseppe is caught returning to the island from Italy, where he had been studying before the war. He finally admits to being a spy, but tries to justify by saying it is his country and he wanted to end his people's suffering.[Note 1]

The RAF holds on, and, along with Royal Navy submarines, is eventually able to take the offensive, targeting enemy shipping on its way to Rommel's Afrika Korps in Libya. Spitfires are flown in from aircraft carriers to defend the island, while attacks are carried out by aircraft such as Bristol Beaufighter fighter-bombers and Bristol Beaufort and Fairey Albacore torpedo bombers.

Then a crucial enemy convoy sails for Libya under cover of poor visibility. Frank needs desperately to locate it; he orders Peter to find it at any cost and to radio in immediately if he does. Peter, flying in his Spitfire, finally spots it, but after he reports its position, he is attacked by six enemy fighters and killed, while Maria in the operations room listens helplessly to his final radio transmissions. When there are no more messages, she picks up Peter's marker from the operations table.

Later, a newspaper article reports that Rommel has lost the Second Battle of El Alamein (in part due to supply shortages).

Cast[edit]

As appearing in Malta Story, (main roles and screen credits identified):[3]

- Alec Guinness as Flight Lieutenant Peter Ross

- Jack Hawkins as Air Vice Marshal Frank

- Anthony Steel as Wing Commander Bartlett

- Muriel Pavlow as Maria Gonzar

- Renée Asherson as Joan Rivers

- Hugh Burden as Eden, Security

- Nigel Stock as Giuseppe Gonzar (aka Ricardi)

- Reginald Tate as Vice Admiral Payne

- Ralph Truman as Vice Admiral Willie Banks

- Flora Robson as Melita Gonzar, Maria's and Giuseppe's mother

- Ronald Adam as Operations Room controller (uncredited)

- Derek Aylward as uncredited

- Peter Barkworth as Cypher Clerk (uncredited)

- Ivor Barnard as Old Man (uncredited)

- Peter Bull as Flying Officer (uncredited)

- Stuart Burge as Paolo Gonzar, Maria's brother (uncredited)

- Edward Chaffers as Stripey (uncredited)

- Michael Craig as British officer (uncredited)

- Rosalie Crutchley as Carmella Gonzar, Paolo's wife (uncredited)

- Maurice Denham as British officer (uncredited)

- Jerry Desmonde as General (uncredited)

- Thomas Heathcote as a radar operator (uncredited)

- Gordon Jackson as soldier, Army airfield defence troop (uncredited)

- Geoffrey Keen as Sergeant Major, Army airfield defence troop (uncredited)

- Dermot Kelly as British soldier at airport (uncredited)

- Sam Kydd as soldier, Army airfield defence troop (uncredited)

- Richard Leven as soldier (uncredited)

- Colin Loudan as O'Connor (uncredited)

- Victor Maddern as soldier, Army airfield defence troop (uncredited)

- Michael Medwin as Ramsey, CO 'Phantom' Squadron (uncredited)

- Lee Patterson as officer on truck (uncredited)

- William Russell as officer at prison (uncredited)

- Marc Sheldon as uncredited

- Harold Siddons as Matthews, bomber pilot (uncredited)

- Noel Willman as Hobley, Navy pilot (uncredited)

Production[edit]

Development[edit]

The film was the idea of the Labour Government's Central Office of Information, who wanted a movie to illustrate co-operation between the three branches of the armed services during World War Two, and thought the Siege of Malta was an ideal background. Producer Peter de Sarigny, director Thorold Dickinson and writer William Fairchild set up a company, Theta, to make it.

The movie was originally called The Bright Flame and was about the story of the actual siege with a fictional story about Lt Ross, who falls in love with a Maltese girl, Maria, whose brother is hanged as a spy by the British. Ross is shot down on a mission but survives and is visited by Maria's mother, who remains loyal to Britain.[4]

J. Arthur Rank and John Davis, who ran Rank Productions, wanted the film to move in a different direction. Nigel Balchin was hired to rewrite the script, adding a plot line to emphasise the loneliness of command, emphasised the British characters over the Maltese, and having Ross die at the end, but after having obtained information to help the British win at the Battle of El Alamein. Dickinson was replaced as director by Brian Desmond Hurst.[4]

The Ulster born director Brian Desmond Hurst was persuaded by his lifelong friend, John Ford, to direct the Malta Story. Ford told Hurst, "it's right up your street."[5][6] Hurst says Alec Guinness approached him asking to play the role of Ross, saying he wanted a change of pace.[4]

Shooting[edit]

The unique footage used in the Malta Story is actual historic archive material. In the aerial sequences, combat footage of aircraft that attacked Malta, such as the Italian Savoia-Marchetti SM.79 torpedo/horizontal bomber and the German Messerschmitt Bf 109F fighters and Junkers Ju 88 bombers can be seen, along with many other wartime RAF aircraft.[2] Additionally, many scenes were shot in Malta with the real types of aircraft still in operational service at that time, some of which did not exist any longer elsewhere. The production only had the use of three later Supermarine Spitfire Mk XVIs, which had been located in storage.[7] Although a modicum of model work and studio rear projection footage was needed, careful editing of archival newsreel and location photography created an authentic looking, near-documentary style.[5][Note 2]

Alec Guinness, cast and playing against type,[5] as part of the Old Vic Company, had played in Malta as part of a tour that had travelled to Portugal, Egypt, Italy and Greece in 1939.[8] Guinness had served in the Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve during the Second World War, joining first as a seaman in 1941 and being commissioned the following year, and actually serving in the Mediterranean Theatre. [Note 3] [Note 4] During the Malta Story production, he found that he was drawn to the social life of the large Royal Navy base on the island, often joining with servicemen at the local "watering holes."[11]

The Fast Minelaying Cruiser HMS Manxman is mentioned by name in the film as bringing Vice-Admiral Payne to Malta to relieve Vice-Admiral Willie Banks. In the film Manxman is briefly depicted by a Dido-class cruiser – clearly identifiable from her 5.25-inch gun turrets which were unique to this cruiser class. (HMS Manxman herself was coincidentally used in another 1953 film which was also shot in Malta. This was Sailor of the King, in which she depicted the fictional German raider Essen. This film also used the Dido-class Cruiser HMS Cleopatra, which was then operating as part of the Mediterranean Fleet).

It was one of several war films Anthony Steel made where he played in support of an older male actor.[12]

Reception[edit]

Box office[edit]

Malta Story was the fourth most popular movie at the British box office in 1953.[13] "The combination of an A-list cast, the portrayal of the iron resilience of the Maltese people, the gallantry of the RAF pilots and a tragic love story were the four components of its success."[14]

Critical reception[edit]

Contemporary reviews judged Malta Story to be a fairly average war picture.

In a contemporary review in The New York Times, critic A. H. Weiler considered it "restrained, routine fare" with "rickety, stock love stories," concluding that "the commendable British reserve [the characters] display in the face of peril does not add luster to the standard yarn in which they are involved. This 'Malta Story,' unlike the actual one, does not stir the senses or send the spirit soaring."[15]

Variety wrote that the film had some "highly dramatic moments," but found that "this type of war story no longer packs the big punch. It's like watching a slightly aged film with its characters out of relation to present times." The review added that Guinness "isn't given much of a chance to emote and his performance therefore is slightly disappointing."[16]

John L. Scott of the Los Angeles Times called the film "long on bombing scenes but somewhat short on human drama."[17] The Monthly Film Bulletin wrote, "The action scenes are, as expected, capably handled. But the film misses out entirely on characterisation. Most of the men are pure 'Boys Own Paper,' all clean-cut profiles and noble, far-seeing gazes."[18] John McCarten of The New Yorker wrote, "Regrettably, there is lacking—as there is in most fictionalized accounts of war—some of the awful impact of impersonal horror that can be caught in documentary films, and the plot spins slowly from a familiar dramatic spool."[19] Richard L. Coe of The Washington Post found the romance subplot "too pat and self-consciously contrived to give much life to the film," but praised the battle scenes, concluding: "Robert Krasker's on-the-spot photography and the clips from wartime film records are splendid and give 'Malta Story' its essential spirit.[20]

In a later review of Malta Story, Leonard Maltin commented that "on-location filming of this WW2 British-air-force-in-action yarn is sparked by underplayed acting."[21] Aviation film historians, Jack Hardwick and Ed Schnepf gave it a 3/5 rating, noting the use of period aircraft made it "good buff material".[22]

In 1955 Guinness called it his "worst" movie "because of the lost time element".[23]

Books[edit]

Theirs is the Glory: Arnhem, Hurst and Conflict on Film takes Hurst's Battle of Arnhem epic as its centrepiece and then chronicles Hurst's life and experiences during the First World War and profiles each of his other nine films on conflict, including Malta Story.[24]

References[edit]

Well known that Fairey Swordfish had open cockpits while Albacores, looking superficially similar, possessed canopy enclosed in crew and pilot compartments.

Wings of the Navy, Captaincies, Eric Brown, Published by Naval Institute Press, 1980.

Notes[edit]

- ^ The plotline involving the character, Giuseppe Gonzar, has some parallels to the real story of Carmelo Borg Pisani.

- ^ The Spitfires shown in action are, however, mainly of the later types that flew from Malta after 1943–44. In 1942, the RAF was mainly using the V type, that appears rarely in the film.

- ^ Guinness is listed in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve (RNVR) under the name Alec Guinness Cuffe.[9]

- ^ Guinness commanded a landing craft taking part in the invasion of Sicily and Elba and later ferried supplies to the Yugoslav partisans.[9][10]

Citations[edit]

- ^ "Malta Story (1953)". BFI. Archived from the original on 25 April 2017. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- ^ a b Parish 1990, p. 268.

- ^ "Credits: Malta Story (1953)." Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved 9 April 2012.

- ^ a b c British Cinema of the 1950s: The Decline of Deference by Sue Harper, Vincent Porter Oxford University Press, 2003 p 38-40

- ^ a b c "Malta Story (1953)." briandesmondhurst.org. Retrieved: 11 January 2012.

- ^ "Thorold Dickinson." The New York Times, 2010. Retrieved 8 April 2012.

- ^ Farmer 1984, p. 53.

- ^ Guinness 1998, p. 114.

- ^ a b Houterman, J.N. "Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve (RNVR) Officers 1940–1945." unithistories.com, 2012. Retrieved 6 June 2012.

- ^ Guinness 2001, p. 40.

- ^ Read 2005, p. 253.

- ^ Vagg, Stephen (23 September 2020). "The Emasculation of Anthony Steel: A Cold Streak Saga". Filmink.

- ^ "From London." Sunday_Mail_(Adelaide, SA: 1912–1954), 9 January 1954, p. 50. via National Library of Australia. Retrieved: 10 July 2012.

- ^ Smith 2010, p. 15.

- ^ Weiler, A. H. (A. W.)."Malta Story (1953): Three Films Arrive; 'Malta Story,' a British Import, at the Guild ..." The New York Times, 17 July 1954.

- ^ "Film Reviews: Malta Story". Variety: 24. 14 July 1954.

- ^ Scott, John L. (September 30, 1954). "Guinness Plays Serious Role in 'Malta Story'". Los Angeles Times. Part III, p. 11.

- ^ "Malta Story". The Monthly Film Bulletin. 20 (235): 118. August 1953.

- ^ McCarten, John (24 July 1954). "The Current Cinema". The New Yorker. p. 40.

- ^ Coe, Richard L. (30 September 1954). "Guiness (sic) Actually Plays It Straight". The Washington Post. p. 36.

- ^ Maltin, Leonard. "Review: Malta Story." Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved 8 April 2012.

- ^ Hardwick and Schnepf 1989, p. 59.

- ^ Guinness Credits Success to Luck Scheuer, Philip K. Los Angeles Times 23 Oct 1955: D1.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-911096-63-4. Publisher Helion and Company and co-authored by David Truesdale and Allan Esler Smith and a foreword by Sir Roger Moore. Available here: http://www.helion.co.uk/new-and-forthcoming-titles/theirs-is-the-glory-arnhem-hurst-and-conflict-on-film.html[permanent dead link]

Bibliography[edit]

- Farmer, James H. Broken Wings: Hollywood's Air Crashes. Missoula, Montana: Pictorial Histories Pub Co., 1995. 2nd edition. ISBN 978-0-9331-2646-6.

- Guinness, Alec. A Positively Final Appearance: A Journal, 1996–1998. London: Penguin Books, 2001. ISBN 978-0140299649.

- Guinness, Alec. My Name Escapes Me. London: Penguin Books, 1998. ISBN 978-0140277456.

- Hardwick, Jack and Ed Schnepf. "A Viewer's Guide to Aviation Movies". The Making of the Great Aviation Films, General Aviation Series, Volume 2, 1989.

- Maltin, Leonard. Leonard Maltin's Movie Guide 2009. New York: New American Library, 2009 (originally published as TV Movies, then Leonard Maltin’s Movie & Video Guide), First edition 1969, published annually since 1988. ISBN 978-0-451-22468-2.

- Parish, James Robert. The Great Combat Pictures: Twentieth-Century Warfare on the Screen. Metuchen, New Jersey: The Scarecrow Press, 1990. ISBN 978-0810823150.

- Read, Piers Paul. Alec Guinness: The Authorised Biography. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005. ISBN 978-0743244985.

- Smith, Allan Esler. "Malta Story (released 1953)- The Director's Cut." Treasures of Malta, Number 48, Vol. XVI, No. 3, Summer 2010. Valletta, Malta: Fondazzjoni Patrimonju Malti in association with the Malta Tourism Authority.

External links[edit]

- Malta Story at IMDb

- Malta Story at the TCM Movie Database

- Malta Story at AllMovie

- Malta Story at Rotten Tomatoes

- Malta Story at BritMovie (archived)

- Malta Story (1953) film review from Film4

- Malta Story at the website dedicated to Brian Desmond Hurst

- 1953 films

- 1950s war films

- 1950s English-language films

- 1950s British films

- British war films

- British black-and-white films

- British aviation films

- Maltese-language films

- World War II aviation films

- Aerial reconnaissance

- Malta in World War II

- World War II films based on actual events

- Films about the Royal Air Force

- Films directed by Brian Desmond Hurst

- Films scored by William Alwyn

- Films with screenplays by Nigel Balchin

- Films set in 1942

- Films set in Malta

- Films shot at Pinewood Studios

- United Artists films