Ludwig Kaas

Last updatedLudwig Kaas | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Kaas at the signing of the Reichskonkordat . | |||||||

| Chairman of the Centre Party | |||||||

| In office September 1928 –5 May 1933 | |||||||

| Preceded by | Wilhelm Marx | ||||||

| Succeeded by | Heinrich Brüning | ||||||

| Member of the Reichstag | |||||||

| In office 1920–1933 | |||||||

| Constituency | Koblenz-Trier | ||||||

| Member of the Weimar National Assembly | |||||||

| In office 6 February 1919 –21 May 1920 | |||||||

| Personal details | |||||||

| Born | 23 May 1881 Trier,German Empire | ||||||

| Died | 15 April 1952 (aged 70) Rome,Italy | ||||||

| Resting place | St. Peter's Basilica | ||||||

| Nationality | German | ||||||

| Political party | Centre Party | ||||||

| Occupation | Priest,politician | ||||||

Ordination history | |||||||

| |||||||

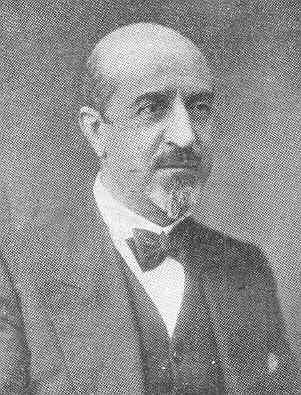

Ludwig Kaas (23 May 1881 – 15 April 1952) was a German Roman Catholic priest and politician of the Centre Party during the Weimar Republic. He was instrumental in brokering the Reichskonkordat between the Holy See and the German Reich. [1]

Contents

Early career

Born in Trier,Kaas was ordained a priest in 1906 and studied history and Canon law in Trier and Rome. In 1906 he completed a doctorate in theology and in 1909 he obtained a second doctorate in philosophy. [2] In 1910 he was appointed rector of an orphanage and boarding school near Koblenz. Until 1933,he devoted his spare time to scholarly pursuits. In 1916 he published the book "Ecclesiastical jurisdiction in the Catholic Church in Prussia" (Die geistliche Gerichtsbarkeit der katholischen Kirche in Preußen in Vergangenheit und Gegenwart mit besonderer Berücksichtigung des Wesens der Monarchie),demonstrating his expertise in church history,Canon law and his political interests. In 1918 he requested to be sent to a parish,but Michael Felix Korum of Trier refused and instead appointed him professor of canon law at the Trier seminary in 1918. In that position,he published the study "Missing in war and remarriage in state law and canon law" (Kriegsverschollenheit und Wiederverheiratung nach staatlichen und kirchlichen Recht),dealing with remarriage in case of spouses missing in war. In 1919 he was offered the chair for canon law at the university of Bonn and was initially inclined to accept it,but as he did not find the conditions in Bonn to his liking and after consultation with Bishop Korum he refused the offer. [3]

Entry into politics

Distressed by the revolution,Kaas also decided to engage in politics and joined the Centre Party. In 1919 he was elected to the Weimar National Assembly and in 1920 to the Reichstag,of which he was a member until 1933. He was also elected to the Prussian State Council,the representation of Prussia's provinces. As a parliamentarian Kaas specialized in foreign policy. From 1926 to 1930 he was a German delegate to the League of Nations. [2]

Kaas considered himself a "Rhenish Patriot" and advocated the creation of a Rhineland state within the framework of the German Reich. In 1923,a year of crisis,he –just like Konrad Adenauer,then mayor of Cologne –fought the separatists that wanted to break away the Rhineland from Germany. Despite French occupation,he sought reconciliation with France and voiced this desire in a famous Reichstag speech on 5 December 1923.

Despite personal reservations towards the Social Democrats (SPD),he developed a cordial relationship with President Friedrich Ebert and willingly acknowledged the SPD's accomplishments after 1918. Kaas supported foreign minister Stresemann's policy of reconciliation and denounced nationalist agitation against this policy - agitation he considered to be irresponsible.

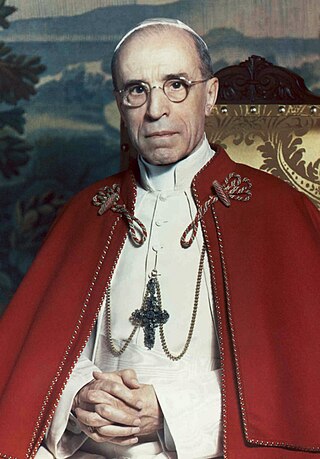

Advisor to the Nuncio Pacelli

In 1920,Eugenio Pacelli,the Papal Nuncio to Bavaria,was also appointed Nuncio to Germany. In view of this new position,he asked Cardinal Adolf Bertram of Breslau,to provide him with experts who might serve as a link between the Nuncio in Munich and the Prussian bishops. Bertram suggested Kaas,who in his academic work had developed a special interest in the relations between the state and the Catholic Church. [4]

The workload as a professor,a parliamentarian and as advisor to the Nuncio strained Kaas's energies. Though Kaas tried to convince himself that his primary obligation was to his own diocese,it was his academic post that always came out last. In 1922 he was prepared to resign his chair,but Bertram and Pacelli insisted that he should stay until he had obtained a secure position within the diocese that would not hinder his external commitments. Bertram,following Pacelli's wishes,proposed to the new bishop of Trier,Franz Rudolf Bornewasser,to make Kaas a cathedral canon,but the bishop refused. An angry Kaas announced he would give up all his other commitments and concentrate on his academic work,but eventually he was reconciled to Bornewasser. On 1 April 1924,Kaas was appointed to the Cathedral chapter. [3]

Bishop Bornewasser had allowed Kaas to keep his parliamentary seat until September 1924,but expected him to resign it afterwards and concentrate on his administrative and academic work within the diocese. However,Pacelli asked the bishop not to insist on this as it would "substantially hinder the hitherto influential work of Dr. Kaas and damage an effective representation of ecclesiastical interests in a deplorable way". Bornewasser,though legally in a stronger position,yielded to these considerations of expediency and did not press his demand again. In the same year,Kaas resigned from his academic chair. [3]

Pascalina Lehnert,writing after Pacelli had already become Pope Pius XII,described the relationship between Kaas and Pacelli in the following words:

Talent, vision, and an excellent knowledge of the situation made Kaas a great advisor and incalculable helper. He was a fast learner, a hard and reliable worker with good judgement. The Nuncio, Cardinal and Holy Father (i.e., the Pope) appreciated him very much. Again and again I heard the highest praises from Pope Pius XII. The Monsignore knew, that the Holy Father had special esteem for him and he told me how much this knowledge fulfils him. [5]

In 1925, as Pacelli was also appointed Apostolic Nuncio to Prussia and moved his office to Berlin, the cooperation between Pacelli and Kaas became even closer. Out of this involvement grew a formal but close and lasting friendship, which remained one of the basic factors throughout Kaas's life. In this position Kaas contributed to the successful conclusion of the Prussian Concordat negotiations with Prussia in 1929.

After this achievement, Pacelli was called back to the Vatican to be appointed Cardinal Secretary of State. Pacelli asked Kaas, who had accompanied him on his travel, to stay in Rome but Kaas declined because of his ecclesiastical and political duties in Germany. Nonetheless, Kaas would frequently travel to Rome, where he would stay with Pacelli, and experience first hand the conclusion of the Lateran Treaty, which he penned an article on. In 1931 and 1932 continued as an advisor in negotiations for a Reichskonkordat; that, however, came to nothing. [6]

In 1929, Kaas published a volume of Nuncio Pacelli's speeches. In the introduction, he described him as: “Angelus not nuntius, ... his impressive personality, his sacerdotal words, the popularity he generated in public meetings" [7]

Kaas as party chairman

Without being a candidate, September 1928 Kaas was elected chairman of the Centre Party, in order to mediate the tension between the party's wings and to strengthen their ties with the Bishops. [8] Under Kaas' watch, the Centre began drifting steadily rightward. Much of his time was occupied in arranging a Reich-wide Concordat. This work made him increasingly distrustful of democracy, and he eventually concluded that only authoritarian rule could protect the interests of the church. [9]

From 1930 onwards, Kaas loyally supported the administration under the Centre's Heinrich Brüning, who served as the leader of the party's Reichstag faction due to Kaas' frequent travel to the Vatican. In 1932 he campaigned for the re-election of President Paul von Hindenburg, calling him a "venerated historical personality" and "the keeper of the constitution". As his frequent Vatican travels hampered his work as chairman, Kaas was prepared to yield the leadership of the party to Brüning, whom Hindenburg had dismissed in May, but the former Chancellor declined and asked the prelate to stay.

In 1932 Kaas and Brüning led the Centre Party into opposition to the new Chancellor: party renegade Franz von Papen. Kaas called him the "Ephialtes of the Centre Party". [10] Kaas tried to re-establish a working parliament by cooperation with the National Socialists.

Hitler's Enabling Act

Kaas felt betrayed when Adolf Hitler became Chancellor on 30 January 1933 based on a coalition between National Socialist German Workers Party (NSDAP), German National People's Party (DNVP) and independent conservatives, which excluded the Centre Party. In the campaign leading up to the election on 5 March, Kaas vigorously campaigned against the new government, but after the government parties succeeded in attaining a majority, he visited Vice Chancellor Papen, offering to put an end to their old animosities.

Later that month, from 15 March, he was the main Centre Party advocate supporting the Hitler administration's Enabling Act [1] in return for certain constitutional and, allegedly [11] ecclesiastic guarantees. Hitler responded positively via Papen. On 21 and 22 March the Centre leadership negotiated with Hitler on the conditions and reached an agreement. A letter, in which Hitler would confirm the agreement in writing, was promised by the government but never delivered.

Kaas — as much as the other party leaders — was aware of the doubtful nature of any guarantees; when the Centre's parliamentary contingent assembled on 23 March to decide on their vote, he still advised his fellow party members to support the bill, given the "precarious state of the contingent", saying: "On the one hand we must preserve our soul, but on the other hand a rejection of the Enabling Act would result in unpleasant consequences for parliamentary membership and party. What is left is only to guard us against the worst. Were a two-thirds majority not obtained, the government's plans would be carried through by other means. The President has acquiesced in the Enabling Act. From the DNVP no attempt of relieving the situation is to be expected." [ citation needed ]

A considerable group of parliamentarians however opposed the chairman's course, among whom were the former Chancellors, his nemesis Heinrich Brüning and Joseph Wirth and former minister Adam Stegerwald. The opponents also argued in regard to Catholic social teaching that ruled out participating in an act of revolution. The proponents however argued that a "national revolution" had already occurred with Hitler's appointment and the presidential decree suspending basic rights, and that the Enabling Act would contain revolutionary force and move the government back to a legal order. Both groupings were not unaffected by Hitler's self-portrayal as a moderate seeking co-operation, as given on the Day of Potsdam of 21 March, as against the more revolutionary SA led by Ernst Röhm.

In the end the majority of Centre parliamentarians supported Kaas's proposal. Brüning and his followers agreed to respect party discipline by also voting in favour of the bill.

On 23 March, the Reichstag assembled at midday under turbulent circumstances. Some SA men served as guards, while others crowded outside the building, both to intimidate any opposing views. Hitler's speech, which emphasised the importance of Christianity to the German culture, was aimed particularly at assuaging the Centre Party's sensibilities and almost verbatim incorporated Kaas's requested guarantees. Kaas gave a speech, voicing the Centre's support for the bill amid "concerns put aside", while Brüning notably remained silent. When parliament assembled again in the evening, all parties except the SPD, represented by their chairman Otto Wels, voted in favour of the Enabling Act. This vote was a major step in the institution of the dictatorship of Adolf Hitler and is remembered as the prime example of a democracy voting for its own demise.

Because of Kaas's request for guarantees and because of his later involvement in the Reichskonkordat negotiations, it is sometimes alleged that Kaas's assent was part of a quid pro quo of interests between the Holy See and the new regime. There is however no evidence for involvement of the Holy See in these dealings [ citation needed ].

Kaas had planned to travel to Rome since the beginning of the year, to discuss a conflict in Eupen and Malmedy, formerly German towns now belonging to Belgium, where priests had been arrested. This trip had been postponed by the political events - first Hitler's appointment, then the March elections, then by the Enabling Act -, but on 24 March, one day after the decision, Kaas finally managed to leave for Rome. During this stay, Kaas explained to Pacelli the Centre's rationale for acceding to the Enabling Act. On 30 March, he was called back to Germany to take part in sessions of the working committee, that had been promised during the Enabling Act negotiations. This committee was chaired by Hitler and Kaas and was supposed to inform about further legislative measures, but it only met three times: on 31 March, on 2 April (followed by a private talk between Kaas and Hitler) and on 7 April. On 5 April Kaas also reported to the foreign office about his talk in the Eupen-Malmedy affair.

Reichskonkordat

On 7 April, directly after the third meeting of the working committee, Kaas once more left Berlin and headed for Rome. The next day, after having changed trains in Munich, the Prelate happened to meet Vice-Chancellor Papen in the dining car. Papen officially went on skiing holidays to Italy, but his real destination was Vatican City, where he was to offer a Reichskonkordat on his government's behalf. Kaas and Papen traveled on together and had some discussions about the matter on the train. After their arrival in Rome, Kaas was received first by Pacelli on 9 April. One day later, Papen had a morning meeting with Pacelli and presented Hitler's offer. Pacelli subsequently authorized Kaas, who was known for his expertise in Church-state relations, to negotiate the draft of the terms with Papen.

These discussions also prolonged his stay in Rome and raised questions in Germany as to a conflict of interest, since as a German parliamentarian he was advising the Vatican. On 5 May Kaas resigned from his post as party chairman, and pressure from the German government forced him to withdraw from visibly participating in the concordat negotiations. Though allegedly the Vatican tried to hold back the exclusion of Catholic clergy and organisations from politics, Pacelli was known to strongly favour the withdrawal of all priests from active politics, which is Church position in all countries even today. In the end, the Vatican accepted the restriction to the religious and charitable field. Even before the Roman negotiations had been concluded, the Centre Party yielded to increasing government pressure and dissolved itself, thus excluding German Catholics from participating in political life.

According to Oscar Halecki, Kaas and Pacelli, "on account of the exclusion of Catholics as a political party from the public life of Germany, found it all the more necessary that the Holy See assure government guarantees to maintain their position in the life of the nation" [12] He maintains that Hitler had from the beginning no other aim than a war of extermination of the Church. [13] Pacelli, now Pope Pius XII, met the German Cardinals on 6 March 1939, three days after his election. He referred to the constant Nazi attacks against the Church, and the Nazi responses to his protests, saying, "They always responded, 'sorry, but we cannot act because the concordat is not legally binding yet'. But after its ratification, things did not get any better, they got worse. The experiences of the past years are not encouraging." [14] Despite this, the Holy See continued diplomatic relations with Germany in order to "connect to the bishops and faithful in Germany". [15] As a result of the Concordat, the Church gained more teachers, more school buildings and more places for Catholic pupils. At the same time it was well known to Pacelli and Pope Pius XI that the Jews were being treated very differently. The Centre Party's vote for the Enabling Act, at Kaas's urging, was an action which fostered the establishment of the Hitlerian tyranny. [16]

At the Vatican

Kaas, who had played a pivotal role in the concordat negotiations, hoped to head an information office, watching over the implementation in Germany. However, Cardinal Bertram considered Kaas to be the wrong man, given his political past. Also, Kaas's conduct was controversial among his fellow party members, who saw his sudden and lasting move to Rome as an act of defection and his involvement in the concordat negotiations as treason to the party. A prime example of this view is Heinrich Brüning, who denounced Kaas in his own memoirs written in exile and not undisputed among historians. [17]

Cardinal Bertram had proposed to elevate Kaas to honours without responsibilities. Accordingly, Kaas was appointed papal protonotary on 20 March 1934 and canon of the Basilica of Saint Peter on 6 April 1935. Meanwhile, the diocese of Trier stripped Kaas of his position in the cathedral chapter of Trier. [17]

The exiled Kaas suffered from homesickness and from the rejection by his fellow party members and the German episcopate. On 20 August 1936, Kaas was appointed Economicus and Secretary of the Holy Congregation of the fabric of St. Peter's Basilica. [17]

Pacelli was elected Pope Pius XII on 2 March 1939. Late in that year, after the outbreak of World War II, Kaas was one of the key figures for the secret Vatican Exchanges, in which Widerstand circles within the German army tried to negotiate with the Allies through the mediation of the Pope Pius XII. Josef Müller, a Bavarian lawyer, would travel to Rome from Berlin with instructions from Hans Oster or Hans von Dohnanyi and confer with Kaas or the Pope's secretary Pater Robert Leiber, in order to avoid direct contact between Müller and the Pope. These exchanges resumed in 1943 after the Casablanca conference, but neither attempt was successful.

After his election, Pius XII had decided to accelerate the archaeological excavations under St. Peter's Basilica and put Kaas in charge. At the Christmas message of the Holy Year 1950, Pius XII presented the preliminary results, which deemed it likely that the tomb of Saint Peter was resting below the Papal altar of the Basilica. Not all questions were solved, and Kaas continued excavations after 1950, despite an emerging illness. [18]

Ludwig Kaas died in Rome in 1952, aged 70. He was first buried in the cemetery of Campo Santo in the Vatican. Later, Pope Pius XII ordered the body of his friend to be put to rest in the crypt of St. Peter's Basilica. Ludwig Kaas is thus the only monsignor who rests in the vicinity of virtually all popes of the twentieth century. To succeed him in his work, Pope Pius XII appointed a woman, Professor Margherita Guarducci, another Vatican novelty. [19]

List of publications

Ludwig Kaas was a scholar and prolific writer, addressing a wide range of issues in Latin or German concerning marital law, education reform, moral and systematic theology, canon law, prisoners of war, the speeches of Eugenio Pacelli, historical issues, policy issues of the Weimar Republic and the Reichskonkordat. Some of his writings were published after his death.

Related Research Articles

Pope Pius XII was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 2 March 1939 until his death in October 1958. Before his election to the papacy, he served as secretary of the Department of Extraordinary Ecclesiastical Affairs, papal nuncio to Germany, and Cardinal Secretary of State, in which capacity he worked to conclude treaties with various European and Latin American nations, including the Reichskonkordat treaty with the German Reich.

The Enabling Act of 1933, officially titled Gesetz zur Behebung der Not von Volk und Reich, was a law that gave the German Cabinet – most importantly, the Chancellor – the power to make and enforce laws without the involvement of the Reichstag or Weimar President Paul von Hindenburg, leading to the rise of Nazi Germany. Critically, the Enabling Act allowed the Chancellor to bypass the system of checks and balances in the government.

The Centre Party, officially the German Centre Party and also known in English as the Catholic Centre Party, is a Christian democratic political party in Germany. Influential in the German Empire and Weimar Republic, it is the oldest German political party in existence. Formed in 1870, it successfully battled the Kulturkampf waged by Chancellor Otto von Bismarck against the Catholic Church. It soon won a quarter of the seats in the Reichstag, and its middle position on most issues allowed it to play a decisive role in the formation of majorities. The party name Zentrum (Centre) originally came from the fact that Catholic representatives would take up the middle section of seats in parliament between the social democrats and the conservatives.

The Reichskonkordat is a treaty negotiated between the Vatican and the emergent Nazi Germany. It was signed on 20 July 1933 by Cardinal Secretary of State Eugenio Pacelli, who later became Pope Pius XII, on behalf of Pope Pius XI and Vice Chancellor Franz von Papen on behalf of President Paul von Hindenburg and the German government. It was ratified 10 September 1933 and it has been in force from that date onward. The treaty guarantees the rights of the Catholic Church in Germany. When bishops take office Article 16 states they are required to take an oath of loyalty to the Governor or President of the German Reich established according to the constitution. The treaty also requires all clergy to abstain from working in and for political parties. Nazi breaches of the agreement began almost as soon as it had been signed and intensified afterwards leading to protest from the Church including in the 1937 Mit brennender Sorge encyclical of Pope Pius XI. The Nazis planned to eliminate the Church's influence by restricting its organizations to purely religious activities.

Mit brennender Sorge is an encyclical of Pope Pius XI, issued during the Nazi era on 10 March 1937. Written in German, not the usual Latin, it was smuggled into Germany for fear of censorship and was read from the pulpits of all German Catholic churches on one of the Church's busiest Sundays, Palm Sunday.

Pietro Gasparri was a Roman Catholic cardinal, diplomat and politician in the Roman Curia and the signatory of the Lateran Pacts. He served also as Cardinal Secretary of State under Popes Benedict XV and Pope Pius XI.

Hitler's Pope is a book published in 1999 by the British journalist and author John Cornwell that examines the actions of Eugenio Pacelli, who became Pope Pius XII, before and during the Nazi era, and explores the charge that he assisted in the legitimization of Adolf Hitler's Nazi regime in Germany, through the pursuit of a Reichskonkordat in 1933. The book is critical of Pius' conduct during the Second World War, arguing that he did not do enough, or speak out enough, against the Holocaust. Cornwell argues that Pius's entire career as the nuncio to Germany, Cardinal Secretary of State, and Pope, was characterized by a desire to increase and centralize the power of the Papacy, and that he subordinated opposition to the Nazis to that goal. He further argues that Pius was antisemitic and that this stance prevented him from caring about the European Jews.

Alois Karl Hudal was an Austrian bishop of the Catholic Church, based in Rome. For thirty years, he was the head of the Austrian-German congregation of Santa Maria dell'Anima in Rome and, until 1937, an influential representative of the Catholic Church in Austria.

Robert Leiber, S.J. was a close advisor to Pope Pius XII, a Jesuit priest from Germany, and Professor for Church History at the Gregorian University in Rome from 1930 to 1960. Leiber was, according to Pius's biographer Susan Zuccotti, "throughout his entire papacy his private secretary and closest advisor".

Francesco Pacelli was an Italian lawyer and the elder brother of Eugenio Pacelli, who would later become Pope Pius XII. He acted as a legal advisor to Pope Pius XI; in this capacity, he assisted Cardinal Secretary of State Pietro Gasparri in the negotiation of the Lateran Treaty, which established the independence of Vatican City.

Cesare Vincenzo Orsenigo was Apostolic Nuncio to Germany from 1930 to 1945, during the rise of Nazi Germany and World War II. Along with the German ambassador to the Vatican, Diego von Bergen and later Ernst von Weizsäcker, Orsenigo was the direct diplomatic link between Pope Pius XI and Pope Pius XII and the Nazi regime, meeting several times with Adolf Hitler directly and frequently with other high-ranking officials and diplomats.

The papacy of Pius XII began on 2 March 1939 and continued to 9 October 1958, covering the period of the Second World War and the Holocaust, during which millions of Jews were murdered by Adolf Hitler's Germany. Before becoming pope, Cardinal Pacelli served as a Vatican diplomat in Germany and as Vatican Secretary of State under Pius XI. His role during the Nazi period has been closely scrutinised and criticised. His supporters argue that Pius employed diplomacy to aid the victims of the Nazis during the war and, through directing his Church to provide discreet aid to Jews and others, saved hundreds of thousands of lives. Pius maintained links to the German Resistance, and shared intelligence with the Allies. His strongest public condemnation of genocide was, however, considered inadequate by the Allied Powers, while the Nazis viewed him as an Allied sympathizer who had dishonoured his policy of Vatican neutrality.

Eugenio Pacelli was a nuncio in Munich to Bavaria from 23 April 1917 to 23 June 1920. As there was no nuncio to Prussia or Germany at the time, Pacelli was, for all practical purposes, the nuncio to all of the German Empire.

Carl-Ludwig Diego von Bergen was the ambassador to the Holy See from the Kingdom of Prussia (1915–1918), the Weimar Republic (1920–1933), and Nazi Germany (1933–1943), most notably during the negotiation of the Reichskonkordat and during the Second World War.

Vatican City pursued a policy of neutrality during World War II, under the leadership of Pope Pius XII. Although the city of Rome was occupied by Germany from September 1943 and the Allies from June 1944, Vatican City itself was not occupied. The Vatican organised extensive humanitarian aid throughout the duration of the conflict.

Popes Pius XI (1922–1939) and Pius XII (1939–1958) led the Catholic Church during the rise and fall of Nazi Germany. Around a third of Germans were Catholic in the 1930s, most of them lived in Southern Germany; Protestants dominated the north. The Catholic Church in Germany opposed the Nazi Party, and in the 1933 elections, the proportion of Catholics who voted for the Nazi Party was lower than the national average. Nevertheless, the Catholic-aligned Centre Party voted for the Enabling Act of 1933, which gave Adolf Hitler additional domestic powers to suppress political opponents as Chancellor of Germany. President Paul Von Hindenburg continued to serve as Commander and Chief and he also continued to be responsible for the negotiation of international treaties until his death on 2 August 1934.

During the pontificate of Pope Pius XI (1922–1939), the Weimar Republic transitioned into Nazi Germany. In 1933, the ailing President von Hindenburg appointed Adolf Hitler as Chancellor of Germany in a Coalition Cabinet, and the Holy See concluded the Reich concordat treaty with the still nominally functioning Weimar state later that year. Hoping to secure the rights of the Church in Germany, the Church agreed to a requirement that clergy cease to participate in politics. The Hitler regime routinely violated the treaty, and launched a persecution of the Catholic Church in Germany.

Formal diplomatic relations between the Holy See and the current Federal Republic of Germany date to the 1951 and the end of the Allied occupation. Historically the Vatican has carried out foreign relations through nuncios, beginning with the Apostolic Nuncio to Cologne and the Apostolic Nuncio to Austria. Following the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire and the Congress of Vienna, an Apostolic Nuncio to Bavaria replaced that of Cologne and that mission remained in Munich through several governments. From 1920 the Bavarian mission existed alongside the Apostolic Nuncio to Germany in Berlin, with which it was merged in 1934.

The Apostolic Nunciature to Bavaria was an ecclesiastical office of the Roman Catholic Church in Bavaria. It was a diplomatic post of the Holy See, whose representative was called the Apostolic Nuncio to Bavaria, a state – consecutively during the nunciature's existence – of the Holy Roman Empire, of its own sovereignty, and then of Imperial, Weimar and finally Nazi Germany. The office of the nunciature was located in Munich from 1785 to 1936. Prior to this, there was one nunciature in the Holy Roman Empire, which was the nunciature in Cologne, accredited to the Archbishop-Electorates of Cologne, Mainz and Trier.

During the Second World War, Pope Pius XII maintained links to the German resistance to Nazism against Adolf Hitler's Nazi regime. Although remaining publicly neutral, Pius advised the British in 1940 of the readiness of certain German generals to overthrow Hitler if they could be assured of an honourable peace, offered assistance to the German resistance in the event of a coup, and warned the Allies of the planned German invasion of the Low Countries in 1940. The Nazis considered that the Pope had engaged in acts equivalent to espionage.

References

- 1 2 Midlarski, Manus I. (21 October 2005). The Killing Trap: Genocide in the Twentieth Century. Cambridge University Press. p. 222. ISBN 978-0521894692.

- 1 2 Biographie: Ludwig Kaas, 1881-1952 Lebendiges Museum Online

- 1 2 3 Volk, Das Reichskonkordat vom 20.7.1933, p. 38-43.

- ↑ Scholder, Die Kirchen und das Dritte Reich, p. 81.

- ↑ Lehnert, Ich durfte ihm dienen, p. 28-29.

- ↑ Volk, Das Reichskonkordat vom 20.7.1933, p. 44-59.

- ↑ Kaas, Eugenio Pacelli, Erster Apostolischer Nuntius beim Deutschen Reich, Gesammelte Reden, p. 24.

- ↑ Klaus Scholder, Die Kirchen und das Dritte Reich, Ullstein, 1986, p.185

- ↑ Evans, Richard J. (2003). The Coming of the Third Reich . New York City: Penguin Press. ISBN 978-0141009759.

- ↑ Klaus Scholder, Die Kirchen und das Dritte Reich, Ullstein, 1986, p.175

- ↑ Heinrich Brüning, Memoirs 1918 - 1934

- ↑ Oscar Halecki, Pius XII, New York, 1951, p.73.

- ↑ Oscar Halecki, Pius XII,New York, 1951, p.74

- ↑ Proces Verbal de la 1. conference, Lettres de Pie XII aux Eveques Allemands, p. 416.

- ↑ Proces Verbal de la 2. conference, Lettres de Pie XII aux Eveques Allemands, p. 424-425.

- ↑ Review by John Cornwell of Hitler's Priests: Catholic Clergy and National Socialism, Kevin P. Spicer (2008) in Church History (2009), pp 235-37.

- 1 2 3 Volk, Das Reichskonkordat vom 20.7.1933, p. 201-212.

- ↑ Tardini, Pio XII, p. 76.

- ↑ Lehnert, Ich durfte ihm dienen, p. 59.

Sources

- Halecki, Oscar. Pius XII, New York (1951).

- Kaas, Ludwig. Eugenio Pacelli, Erster Apostolischer Nuntius beim Deutschen Reich, Gesammelte Reden, Buchverlag Germania, Berlin (1930).

- Lehnert, Pascalina . Ich durfte ihm dienen. Erinnerungen an Papst Pius XII. Naumann, Würzburg (1986).

- Proces Verbal de la 1. conference, Lettres de Pie XII aux Eveques Allemands, Vatican City (1967).

- Proces Verbal de la 2. conference, Lettres de Pie XII aux Eveques Allemands, Vatican City (1967), p. 424–425.

- Scholder, Klaus. Die Kirchen und das Dritte Reich. Ullstein (1986).

- Tardini, Domenico Cardinale. Pio XII, Tipografia Poliglotta Vaticana (1960).

- Volk, Ludwig. Das Reichskonkordat vom 20.7.1933. Mainz (1972).