Nightcrawler (film)

| Nightcrawler | |

|---|---|

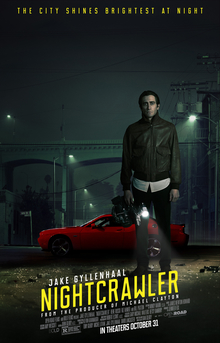

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Dan Gilroy |

| Written by | Dan Gilroy |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Robert Elswit |

| Edited by | John Gilroy |

| Music by | James Newton Howard |

Production company | |

| Distributed by |

|

Release dates |

|

Running time | 117 minutes[2] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $8.5 million[3] |

| Box office | $50.3 million[3] |

Nightcrawler is a 2014 American thriller film directed and written by Dan Gilroy (in his directorial debut) and co-produced by and starring Jake Gyllenhaal, with Rene Russo, Riz Ahmed, and Bill Paxton in supporting roles. Gyllenhaal plays Louis "Lou" Bloom, a stringer who records violent events late at night in Los Angeles and sells the footage to a local television news station. A common theme in the film is the symbiotic relationship between unethical journalism and consumer demand.

Gilroy originally wanted to make a film about the life of American photographer Weegee but switched focus after discovering the unique narrative possibilities surrounding the stringer profession. He wrote Lou as an antihero, based on the ideas of unemployment and capitalism. Gyllenhaal played a pivotal role in the film's production, from choosing members of the crew to watching audition tapes. Filming took place over the course of four weeks and was a challenging process that included over 80 locations.

To promote Nightcrawler, Open Road Films utilized viral marketing strategies, including a fictional video résumé on Craigslist and fake social media profiles for Lou. Nightcrawler premiered at the 2014 Toronto International Film Festival and grossed $50.3 million on a production budget of $8.5 million and gained a cult following[4] over the years. The film was met with widespread praise, with critics highlighting Gilroy's screenplay and Gyllenhaal and Russo's performances. Several critics listed Nightcrawler as one of the best films of 2014 and it received various accolades, including a Best Original Screenplay nomination at the 87th Academy Awards.

Plot[edit]

Petty thief Louis "Lou" Bloom is caught stealing from a Los Angeles railyard by a security guard. He attacks the guard, steals his watch and leaves with stolen manhole covers, fencing, and other materials. While trying to sell the materials at a scrap yard, Lou asks for a job, but the foreman, who has already been questioned by police looking for the manhole covers, refuses to hire a thief. While driving home in his beat-up Toyota Tercel, Lou sees a car crash and pulls over. Stringers—freelance photojournalists—arrive and record two police officers pulling a woman from the burning wreckage. One of the stringers, Joe Loder, explains to Lou that they sell their footage to local news stations.

Inspired, Lou steals an expensive bicycle and pawns it for a camcorder and a police radio scanner. After two unsuccessful attempts at recording incidents, Lou records the aftermath of a fatal carjacking and sells the footage to KWLA 6. The morning news director, Nina Romina, tells him the station is especially interested in footage of "graphic" accidents and violent crime in affluent, predominantly white areas. Lou hires an assistant, Rick, a young homeless man desperate for money. To give his footage more impact, Lou tampers with crime scenes, in one case moving a body to get a better camera angle. As Lou's work gains traction, he buys better equipment and a faster car (a red Dodge Challenger).

Lou pressures Nina into a date, telling her he knows she is desperate for higher ratings. On their date, he threatens to terminate his business with Nina unless she has sex with him, and it is implied that she acquiesces. Lou turns down an offer to work for Joe, but when Joe beats him to an important plane crash story, Nina demands that Lou get better footage and keep his end of their bargain. In retaliation, Lou sabotages Joe's Ford Econoline van; when it crashes, Joe is severely injured and Lou records the aftermath.

Later, Lou and Rick arrive before the police at the site of a triple-homicide home invasion in Granada Hills. Lou records footage of the gunmen leaving in their Cadillac Escalade and of the victims in the house, and later presents footage to the station with the perpetrators edited out. The news staff frets over the ethics of the footage but Nina is eager to break the story. In exchange, Lou demands public credit and more money. Police detective Frontieri shows up at Lou's apartment to question him about his connection to the home invasion. He gives her edited footage of the incident, cutting out the parts with the gunmen.

That night, Lou and Rick track down the driver to his house, staking out the house until he leaves to pick up his partner. Lou wants to follow them to a more crowded public area, then call the police and record the ensuing confrontation. Alarmed, Rick demands half of the reward money for locating the gunmen, threatening to tell the police about Lou's withholding of evidence. After some back-and-forth, Lou agrees.

When the gunmen stop at a restaurant, Lou phones the police, warning them that the suspects are armed. They arrive and exchange gunfire. A police officer is shot and one of the killers is gunned down while the other manages to escape in the Escalade. The police give chase. Lou and Rick follow close behind in the Challenger, filming the chase as it happens, culminating in a long multiple-car collision. After the gunman's Escalade crashes, Lou approaches the vehicle, claiming that the gunman is dead and urging Rick to film him. The gunman is revealed to be alive as he shoots Rick, flees, and is killed by arriving police officers. As Rick lies dying, Lou films him and tells him that he cannot work with someone who successfully extorted him for withholding evidence, because he knows it will happen again.

Nina is awed by the chase footage and expresses her devotion to Lou. The news team discovers that the home invasion was actually the criminals breaking in to steal cocaine that the homeowners were stashing; Nina refuses to report this information to maximize the story's impact. Police try to confiscate Lou's footage as evidence but Nina defends her right to withhold it and airs it immediately. Lou voluntarily speaks with Detective Frontieri. While being interrogated by Frontieri, Lou fabricates a story about the men in the Escalade following him; Frontieri knows he is lying, but cannot prove it. Later, Lou hires a team of interns to expand his business, saying that he will not ask them to do anything he is unwilling to do himself.

Cast[edit]

- Jake Gyllenhaal as Louis "Lou" Bloom[5]

- Rene Russo as Nina Romina[5]

- Riz Ahmed as Rick[5]

- Bill Paxton as Joe Loder[5]

- Kevin Rahm as Frank Kruse[5]

- Michael Hyatt as Detective Frontieri[5]

- Ann Cusack as Linda

Carolyn Gilroy, the daughter of editor John Gilroy and niece of director Dan Gilroy, portrays KWLA 6 employee Jenny. Michael Papajohn, James Huang, Eric Lange, Kiff VandenHeuvel, Myra Turley, and Jamie McShane play a security guard, Joe's video assistant, a cameraman, a news editor, a neighbor, and a motorist, respectively. Detective Lieberman, Frontieri's partner, is portrayed by Price Carson. Journalists Kent Shocknek, Pat Harvey, Sharon Tay, Rick Garcia, and Bill Seward appear as themselves.

Analysis[edit]

According to Dean Biron of Overland, "Nightcrawler is a shattering critique of both modern-day media practice and consumer culture."[6] Throughout the film, Nina sensationalizes news headlines in an attempt to increase viewership. PopMatters' Jon Lisi believes that, because of Nina's actions, the film specifically targets journalists who exaggerate headlines in order to combat a decline in viewership.[7] Ed Rampell of The Progressive offers similar commentary, stating: "Nightcrawler contends that ethnic and class biases are used to determine what is, and is not, deemed 'worthy' of news coverage. Local politics and related matters that actually affect viewers' lives get short shrift."[8] As much as the film indicts modern journalism, Nightcrawler's director Dan Gilroy noted that his goal was for audiences to realize that by watching sensationalized news stories, they themselves are encouraging unethical journalism.[9] Biron argues that Lou's character in the film is created because of consumer demand, and that he is a "reflection of the symbiotic relationship between commercial imperatives and audience desire".[6] Critics Alyssa Rosenberg and Sam Adams argue that Nightcrawler is not so much a critique of journalism, but instead a depiction of Lou's entitlement.[10][11]

The exact genre of Nightcrawler has been the subject of debate.[12] While most critics agree that the film predominantly features thriller elements, other descriptions have been used, including dark comedy,[12][13] drama,[12][14] horror,[14][15] and neo-noir.[16][17] When asked about the film's genre, Gilroy stated: "I see Nightcrawler as having genre elements in the sense that it's a thriller. It also has some strong dramatic elements and I think I understand the question as there's some really strong elements of drama."[12] Gyllenhaal particularly noted the comedic elements, commenting: "Gilroy and I were laughing pretty much the whole movie."[18]

Production[edit]

Development[edit]

Gilroy conceived the idea for Nightcrawler in 1988, after reading the photo-book Naked City, a collection of photographs taken by American photographer Weegee of 1940s New York City residents at night. Often lewd and sensationalized in content, Weegee would sell these photos to tabloid newspapers. Intrigued by what he described as "an amazing intersection of art and crime and commerce", Gilroy wrote a film treatment with a "Chinatown feel".[20] He shelved the idea after the release of The Public Eye (1992), which was loosely based on Weegee's life.[21] Two years later, he moved to Los Angeles, and noted the predominance of violent crime stories on local news stations. "I suddenly became aware of and intrigued by the idea that it must be a powerful force for a TV station, when they realize their ratings go through the roof when they show something with the potential for violence, like a police chase", says Gilroy.[22] Sometime later, he discovered the stringer profession, and considered it to be the modern day equivalent of Weegee.[23] Unaware of any film that focused on the livelihood of stringers, he began writing a screenplay.[24]

Gilroy spent several years trying to write a plot that would fit the setting, and experimented with conspiracies and murder mysteries as central story elements.[16] Eventually, he decided to instead start by designing the characters, and attempted to create a standard literary hero character. Unable to create an interesting hero, he then envisioned an antihero as the lead character. Gilroy felt antiheroes were a rarity in films, because they are difficult to write, and usually devolve into psychopaths; in an attempt to break from the stereotype, he thought of writing an antihero success story.[25] Several films, including The King of Comedy (1982), To Die For (1995), and The Talented Mr. Ripley (1999), were used as research on how to write antiheroes.[24]

To create Lou Bloom's character, Gilroy explored the ideas of unemployment and capitalism. He wanted to portray Lou as someone who perpetually focuses on the precepts of capitalism, and how these thoughts not only give him sanity, but also push him over the edge.[26][27] Gilroy did not give Lou a character arc, as he believed that people develop their ideals at a certain point in their life, and that they stay that way regardless of what happens. This is depicted in the opening scene of the film, when Lou attacks a security guard, which informs the audience that Lou is a criminal, and not someone who lost his morality as a result of the job.[28] Lou's backstory was purposefully left out of the script, as Gilroy felt that without one, the audience would create their own backstories for Lou, and become more engaged with the character.[24] Gilroy remarked that Lou eventually became a vehicle for the ideas and themes that he wanted to express in the film.[29]

Pre-production[edit]

Once the script was finalized, Gilroy knew that he wanted to direct the film. He sent the script to his brother Tony Gilroy, and asked him for advice on directing. His brother described the script as "absolutely compelling", and noted every person who read the script afterwards wanted to work on the project, a rarity in the film industry. The production crew included film editor John Gilroy, cinematographer Robert Elswit, and composer James Newton Howard.[21] Gilroy previously met Elswit while working as a screenwriter for The Bourne Legacy (2012); the two formed a partnership, and created a shot-list for Nightcrawler months before filming.[30] The production team needed licensed background footage for the newsroom scenes, and the Raishbrook brothers, three real stringers, offered their footage.[31] The Raishbrook brothers were eventually brought on as technical advisers.[32]

Gyllenhaal was Gilroy's first choice for the role of Lou. During pre-production, Gyllenhaal was going to star in another film, but that project fell through, allowing time to meet with Gilroy.[21] The two discussed the script in Atlanta, where Gyllenhaal was filming Prisoners (2013).[33] When Gilroy told Gyllenhaal that he wrote Nightcrawler as a success story, Gyllenhaal became interested in the film. "This character was beautifully written. The dialogue is pretty extraordinary. Just even the style of the script was an amazing read", said Gyllenhaal.[34] The two rehearsed the script months before filming began, and Gyllenhaal became heavily involved in production, from choosing members of the crew to watching audition tapes.[21][35] While rehearsing the character, Gilroy mentioned how he saw Lou as a coyote, a nocturnal predator who is driven by its never ending hunger.[33] Gyllenhaal took this comment literally, and lost nearly thirty pounds by eating nothing but kale salads and chewing gum, and running fifteen miles every day.[36] Although some of the crew disagreed with this decision, Gilroy was supportive of the weight loss; Gyllenhaal was respectful and did not alter the script, so Gilroy wanted to reciprocate this generosity.[23]

Riz Ahmed was one of seventy-five actors to audition for the role of Rick.[21] Ahmed was attending a friend's wedding in Los Angeles, when his talent agent suggested he meet Gilroy to discuss the film's script. Gilroy told Ahmed that he had seen his previous work; he was not fit for the role, but still allowed him to audition.[37] Within the first minute of his audition tape, Gilroy felt confident in the actor's abilities.[21] To prepare for the role, Ahmed met with homeless people in Skid Row, and researched homeless shelters to "understand the system". He found that most of the people dealt with abandonment issues, and attempted to replicate this in Rick's abusive relationship with Lou.[37] Additionally, Gilroy, Gyllenhaal, and Ahmed rode with the Raishbrook brothers at night to accurately portray their lifestyle.[38][39]

Gilroy specifically wrote the role of Nina for his wife Rene Russo; this was because he felt that Nina could easily be reduced to a "hard-nosed corporate bitch", but Russo would bring a sense of vulnerability to the character.[21] Although Russo was unaware of Gilroy's intention while writing the script, she was interested in performing the role, as she had never portrayed a desperate woman in a film.[40] Russo initially struggled with the character, because she never saw herself as the victim. In order to accurately portray the character, Russo had to recall memories of when she crossed moral boundaries in her life as a result of desperation and fear. In contrast to the preparations Gyllenhaal and Ahmed took for their roles, Russo did not consult news directors or journalists, as she believed that Nina could be in any business, and did not want to limit her character to one profession.[41]

Filming[edit]

Nightcrawler was filmed on a budget of $8.5 million, most of which was financed by Bold Films.[42][43] Part of the budget came from a $2.3 million California Film Tax Credit, which rewards directors for producing films in California.[43][44] Tony Gilroy noted the budget was extremely low, and should have "easily cost twice that amount".[21] To make the most out of the budget, Elswit built "efficiencies" into each day of the film schedule, a role that all three Gilroy brothers described as instrumental to the completion of the film.[21] Before the filming for Nightcrawler began, the production crew spent two days location scouting across Los Angeles.[21] Some crew members did not believe there was going to be enough time to film every scene, and that at least 15 pages of the script would have to be cut; Gilroy took these comments as a personal challenge.[21] Principal photography began on October 6, 2013, in Los Angeles and lasted 27 days.[25][43] Filming was a challenging and busy process, as 80 locations were used, and there were many times in which the crew had to move to multiple locations each night.[33] Gilroy remarked that there was never a day that filming was not completed minutes before sunrise.[21]

One of the goals while filming Nightcrawler was to portray Los Angeles as having "an untamed spirit, a wildness, a timelessness, about it", and to not let the visuals dictate the dark tone of the script. Gilroy believes that, in contrast to the desaturated, man-made feel that the city is often depicted with, Los Angeles is a "landscape of primal struggle and survival".[30] Gyllenhaal's animalistic approach to the script influenced this belief, and the idea was to film Nightcrawler like a wildlife documentary.[29] To achieve this goal, Elswit used wide-angle lens, depth of field, and avoided soft focus to bring a sense of landscape.[21][30]

Music[edit]

James Newton Howard composed the score for Nightcrawler. Unlike the large and cinematic scores that had previously defined his career, Howard composed moody electronica pieces for Nightcrawler, heavily influenced by 1980s synth.[45] Howard initially struggled writing a score that fit both the overall atmosphere of the film and Gilroy's expectations.[46] Instead of using what Consequence of Sound described as "the expected 10 strings and a nightmarish score", Gilroy wanted more uplifting and subversive music.[47] The goal was for the audience to believe that the music is actually playing inside Lou's mind. For example, in the scene when Lou moves a dead body to get a better angle, the music sounds triumphant instead of dark, which is meant to convey how excited Lou is about the shot. Howard describes this as "an anthem of potential for his tremendous success".[46] For shots of Los Angeles, Howard used a subtle electronic sound, while shots with Lou used a more orchestral, clarinet-driven sound. He believed that Lou could go through difficult situations easily and with a certain intelligence, and that orchestral music would best suit Lou.[46]

Marketing[edit]

According to Open Road Films CEO Tom Ortenberg, the company attempted to market Nightcrawler to both mainstream audiences and art house critics. "We had material that portrayed the picture as the commercial property that it is, but not while abandoning its indie roots", says Ortenberg.[48] The first trailer was released on July 23,[49] while a red band trailer was released on October 24.[50] In addition to typical trailers, Nightcrawler also used some unusual viral marketing strategies. On July 19, a fictional video résumé for Lou was posted on Craigslist. In the video, Lou discusses his benefits for potential employers.[51] A few months later, LinkedIn and Twitter profiles were created for Lou. These profiles purport the video production business that Lou runs in the film to be real, and endorse Lou's management and strategic planning skills.[11]

Release[edit]

An unfinished version of Nightcrawler was screened on May 16, at the 2014 Cannes Film Festival; the film sparked a bidding war between several distribution companies, including A24, Focus Features, Fox Searchlight Pictures, Open Road Films, and The Weinstein Company.[1] Open Road Films acquired the distribution rights in the United States for around $4.5 million.[52] Nightcrawler had its world premiere on September 5, at the 2014 Toronto International Film Festival.[53] It also screened at several other film festivals, including the Atlantic Film Festival,[54] Fantastic Fest,[55] and the Rome Film Festival.[56] The film was originally scheduled for a theatrical release on October 17, but Open Road Films moved the release to October 31, to avoid competition with several bigger-budget films like Fury, Birdman, Dracula Untold, and The Book of Life.[57]

Home media[edit]

Nightcrawler was released on DVD and Blu-ray formats on February 10, 2015,[58] courtesy of Universal Pictures Home Entertainment.[59] Special features on the Blu-ray release include an audio commentary in which the three Gilroy brothers discuss the film's production, and a five-minute making-of video with behind-the-scenes shots and interviews.[59] In its first week of DVD and Blu-ray release, Nightcrawler sold 67,132 units, and grossed $1.1 million. In its second week, the film dropped sixty-seven percent in sales, and made $371,442, for an overall total of $1.5 million.[60]

Reception[edit]

Box office[edit]

In North America, Nightcrawler earned $500,000 from early screenings, and after opening to 2,766 theaters, grossed $3.2 million on its first day of release.[48][61] It finished its opening weekend with $10.9 million;[62] journalists attributed the low sales to Halloween festivities.[61][62] In its second weekend, Nightcrawler dropped forty-nine percent in sales, and grossed $5.4 million.[63] After grossing $28.8 million by December, Nightcrawler reentered North American theaters due to several nominations during the 2014 film awards season.[64] The film eventually finished with $32.4 million in North America.[42]

In the United Kingdom, Nightcrawler opened to £1 million ($1.33 million), and grossed an additional £545,221 ($725,563) in its second weekend.[65][66] The film would eventually earn $18 million in international territories, and when combined with its North American sales, earned $50.3 million.[42] Despite its low production budget, Ortenberg believes that Nightcrawler was able to succeed at the box office by word-of-mouth marketing. "College kids, cinephiles, mainstream moviegoers across the country as well as critics and bloggers started taking possession of Nightcrawler as their own and championed it. It became a cause for people to promote it and get it seen", says Ortenberg.[48]

Critical response[edit]

The website Rotten Tomatoes aggregated an approval rating of 95% for the film based on 279 reviews and an average rating of 8.3/10. The site's critical consensus reads: "Restless, visually sleek, and powered by a lithe star performance from Jake Gyllenhaal, Nightcrawler offers dark, thought-provoking thrills."[67] On Metacritic, the film has a score of 76 out of 100, based on reviews from 45 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[68] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "B−" on an A+ to F scale.[69]

Reviewers call Gyllenhaal's character a "charming sociopath" and his performance "a bravura, career-changing tour-de-force".[70][71] Film critic Christy Lemire called Gyllenhaal's performance "supremely creepy" and praised the film's themes and messages.[72] Christopher Orr of The Atlantic compared Gyllenhaal to a young Robert De Niro and his performances in the films Taxi Driver (1976) and The King of Comedy, feeling Gyllenhaal's character harbored traits shared by De Niro's characters in the two films. Orr called Gyllenhaal "tremendous" in the role and stated that the actor was learning to "channel an eerie, inner charisma, offering it up in glimpses and glimmers rather than all at once". He also declared the role as Gyllenhaal's "best performance to date".[73] Ben Sachs of the Chicago Reader highlighted Gilroy's direction, and how he was able to command an "uncommon assurance" from the cast and crew, despite being a first time director.[74] Conversely, Richard Roeper felt that Gyllenhaal's performance was merely good, and that it did not enter "new dramatic territory". He also found that Russo's character eventually becomes a caricature.[75]

Keith Uhlich of The A.V. Club named Nightcrawler the eighth-best film of 2014.[76] Its screenplay was ranked the ninth best of the 2010s in WhatCulture: "This feverous script succeeds because it contains one of modern cinema's greatest character [sic], Lou Bloom- macabre, ruthless, brazenly tranquil yet simmering with a latent violence [...] Gilroy opts for one-word sentences which zip across the page like Bloom's Dodge Challenger tearing down the interstate for the next car crash or burn victim." The writer also argued that the trajectory of the main character "plays to our guilt over our voyeurism- we consume the footage which men like Bloom provide, we allow the likes of him to rise in society".[77]

Accolades[edit]

Nightcrawler was nominated for several awards, most of which went to Gyllenhaal's performance and Gilroy's screenplay. At the 87th Academy Awards, Gilroy was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay.[78] The film received an additional four nominations at the 68th British Academy Film Awards, three nominations at the 20th Critics' Choice Awards, one nomination at the 72nd Golden Globe Awards, and one nomination at the 21st Screen Actors Guild Awards, but did not win any of them.[79][80][81][82] It did, however, win Best Film at the 19th San Diego Film Critics Society Awards.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b McClintock, Pamela (May 16, 2014). "Cannes: Jake Gyllenhaal's 'Nightcrawler' Sparks Bidding War". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on August 25, 2017. Retrieved August 25, 2017.

- ^ "Nightcrawler". British Board of Film Classification. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved October 3, 2014.

- ^ a b "Nightcrawler (2014)". The Numbers. Archived from the original on August 20, 2016. Retrieved March 19, 2017.

- ^ Porzio, Stephen (July 29, 2023). "A modern cult classic is among the movies on TV tonight". JOE.ie. Retrieved March 13, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f "Nightcrawler (2014)". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on December 23, 2017. Retrieved December 22, 2017.

- ^ a b Biron, Dean (February 6, 2015). "Nightcrawler: a moral dilemma of our own making". Overland. Archived from the original on March 25, 2016. Retrieved November 3, 2016.

- ^ Lisi, Jon (February 9, 2015). "'Nightcrawler' Reminds Us That Capitalism and the Media Have Gotten Worse". PopMatters. Archived from the original on October 28, 2016. Retrieved October 27, 2016.

- ^ Rampell, Ed (October 31, 2014). "Nightcrawler: Journalism's Creepy Ethics". The Progressive. Archived from the original on October 28, 2016. Retrieved October 27, 2016.

- ^ Fleming, Mike Jr. (November 2, 2014). "Dan and Tony Gilroy of 'Nightcrawler' Talk Media Ugliness In The Digital Age: Q&A". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on October 26, 2016. Retrieved November 5, 2016.

- ^ Rosenberg, Alyssa (November 3, 2014). "'Nightcrawler' and the new face of entitlement". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on May 11, 2017. Retrieved April 11, 2017.

- ^ a b Adams, Sam (October 17, 2014). "Jake Gyllenhaal's 'Nightcrawler' Character Is on LinkedIn". IndieWire. Archived from the original on April 12, 2017. Retrieved April 11, 2017.

- ^ a b c d Wolfe, Clarke (October 31, 2014). "Writer/Director Dan Gilroy On His New Thriller Nightcrawler". Nerdist News. Archived from the original on February 3, 2017. Retrieved January 30, 2017.

- ^ Lawson, Richard (September 8, 2014). "Jake Gyllenhaal Hones His Puckish Intelligence to a Scary Edge in Nightcrawler". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on April 13, 2016. Retrieved January 30, 2017.

- ^ a b Tilly, Chris (September 6, 2014). "Nightcrawler Review". IGN. Archived from the original on February 3, 2017. Retrieved January 30, 2017.

- ^ Macnab, Geoffrey (October 30, 2014). "Nightcrawler, film review: Jake Gyllenhaal stars in a warped snapshot of the American dream". The Independent. Archived from the original on February 13, 2017. Retrieved January 30, 2017.

- ^ a b Ward, Tom (February 20, 2015). "Nightcrawler: How Dan Gilroy Made The Most Original Film Of The Year". Esquire. Archived from the original on August 17, 2016. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ^ Feinberg, Scott (September 6, 2014). "Toronto: Can the Acclaimed Genre Film 'Nightcrawler' Crack Into Oscar Race?". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on February 3, 2017. Retrieved January 30, 2017.

- ^ Sullivan, Kevin P. (October 31, 2014). "'Nightcrawler' Is The Only Movie You Need To Watch On Halloween". MTV. Archived from the original on February 3, 2017. Retrieved January 30, 2017.

- ^ Chitwood, Adam (June 26, 2017). "'Nightcrawler' Team of Gyllenhaal, Russo, and Dan Gilroy Reuniting for Netflix Film". Collider. Archived from the original on August 24, 2017. Retrieved August 24, 2017.

- ^ Friend, Tad (November 10, 2014). "Rembrandt Lighting". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on August 21, 2016. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Nightcrawler Blu-ray edition (Audio commentary). Dan Gilroy, John Gilroy, Tony Gilroy. Universal Studios Home Entertainment. 2015.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ Pappademas, Alex (October 31, 2014). "Through the Lens Glass: 'Nightcrawler' Filmmaker Dan Gilroy on Car Chases, Screenwriting, and the Internet's Latchkey Kids". Grantland. Archived from the original on August 24, 2017. Retrieved February 1, 2017.

- ^ a b Hammond, Pete (January 7, 2015). "Oscars: Dan Gilroy Taking Creepy 'Nightcrawler' Deep Into Race With Sterling Directorial Debut". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on August 8, 2016. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ^ a b c Britt, Thomas (February 23, 2015). "An Interview With Dan Gilroy of 'Nightcrawler'". PopMatters. Archived from the original on August 28, 2016. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ^ a b Sragow, Michael (February 10, 2015). "Interview: Dan Gilroy". Film Comment. Archived from the original on August 19, 2016. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ^ Rocchi, James (October 29, 2014). "Interview: 'Nightcrawler' Director Dan Gilroy Talks Jake Gyllenhaal, Robert Elswit & Sociopaths". IndieWire. Archived from the original on October 27, 2017. Retrieved August 21, 2016.

- ^ Mitchell, Elvis (October 29, 2014). "Dan Gilroy: Nightcrawler". KCRW. Archived from the original on August 22, 2016. Retrieved August 21, 2016.

- ^ Bailey, Jason (February 6, 2015). ""I Did Not Want a Character With an Arc": 'Nightcrawler' Filmmaker Dan Gilroy on His Oscar Nomination, Jake Gyllenhaal, and Crime Scene Photography". Flavorwire. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved August 21, 2016.

- ^ a b Sollosi, Mary (October 27, 2014). ""It Had to Be Los Angeles." Director Dan Gilroy on Nightcrawler's Untamed Energy". Film Independent. Archived from the original on October 25, 2016. Retrieved October 24, 2016.

- ^ a b c Ralske, Josh (Fall 2014). "Exploring The Dark Places". MovieMaker. 21 (111): 40–43.

- ^ Utichi, Joe (December 29, 2014). "Three English Brothers Are The Real-Life Nightcrawlers Who Inspired Jake Gyllenhaal's Lou Bloom". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on September 13, 2016. Retrieved September 14, 2016.

- ^ Zeitchik, Steven (November 12, 2014). "Movie fiction mirrors fact for L.A.'s real-life 'nightcrawlers'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on September 1, 2016. Retrieved September 14, 2016.

- ^ a b c "Interview: Nightcrawler director Dan Gilroy". Raidió Teilifís Éireann. October 30, 2014. Archived from the original on August 24, 2017. Retrieved September 14, 2016.

- ^ Hammond, Pete (November 29, 2014). "Gyllenhaal Harnesses A Coyote Spirit In 'Nightcrawler' – Awardsline Q&A". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on April 7, 2017. Retrieved April 6, 2017.

- ^ Fischer, Russ (October 31, 2014). "Interview: 'Nightcrawler' Director Dan Gilroy on Manipulation and Ditching the Character Arc". /Film. Archived from the original on September 18, 2016. Retrieved September 14, 2016.

- ^ Lee, Chris (October 23, 2014). "You Don't Know Jake". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on November 21, 2016. Retrieved October 22, 2016.

- ^ a b Black, Claire (November 2, 2014). "Riz Ahmed winning rave reviews for new film role". The Scotsman. Archived from the original on September 19, 2016. Retrieved September 14, 2016.

- ^ Pitts, Byron; Litoff, Alyssa; Effron, Lauren (October 27, 2014). "How a Coyote and Real-Life News Stringer Helped Jake Gyllenhaal Prepare for 'Nightcrawler' Role". ABC News. Archived from the original on March 18, 2016. Retrieved September 14, 2016.

- ^ "Nightcrawler Interview — Riz Ahmed (2014) — Dan Gilroy Crime Drama". Movieclips. October 29, 2014. Archived from the original on October 27, 2017. Retrieved September 14, 2016.

- ^ Aftab, Kaleem (October 17, 2014). "Rene Russo, interview: Actress back with a bang in new film Nightcrawler". The Independent. Archived from the original on November 28, 2014. Retrieved September 14, 2016.

- ^ Vineyard, Jennifer (January 4, 2015). "Rene Russo on Nightcrawler, Career Regrets, and Not Having a Sex Scene With Jake Gyllenhaal". Vulture.com. Archived from the original on December 21, 2016. Retrieved September 12, 2016.

- ^ a b c "Nightcrawler (2014)". The Numbers. Archived from the original on August 20, 2016. Retrieved September 6, 2016.

- ^ a b c McNary, Dave (September 19, 2013). "Jake Gyllenhaal's 'Nightcrawler' Gets California Incentive (Exclusive)". Variety. Archived from the original on November 1, 2013. Retrieved October 23, 2013.

- ^ "California Film & Television Tax Credit Program 2.0". California Film Commission. Archived from the original on October 13, 2016. Retrieved October 24, 2016.

- ^ Loring, Allison (November 13, 2014). "The Electric Side of James Newton Howard". Film School Rejects. Archived from the original on August 25, 2017. Retrieved August 25, 2017.

- ^ a b c Murphy, Mekado (December 10, 2014). "Below the Line: Scoring 'Nightcrawler'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 25, 2017. Retrieved August 25, 2017.

- ^ Roffman, Michael (December 15, 2014). "Filmmaker of the Year: Dan Gilroy". Consequence of Sound. Archived from the original on May 20, 2017. Retrieved August 25, 2017.

- ^ a b c Brooks, Brian (December 30, 2014). "How 'Nightcrawler' Found Daylight At The Boxoffice". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on November 5, 2016. Retrieved November 1, 2016.

- ^ McNary, Dave (July 23, 2014). "Watch: Jake Gyllenhaal's 'Nightcrawler' Releases First Trailer". Variety. Archived from the original on August 25, 2017. Retrieved August 25, 2017.

- ^ Fleming, Mike Jr. (October 24, 2014). "Hot Red Band Trailer: 'Nightcrawler'". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on June 22, 2017. Retrieved August 25, 2017.

- ^ Kapsch, Joseph (July 19, 2014). "Jake Gyllenhaal First Look as 'Nightcrawler' Surfaces in Craigslist Video: 'Hard Worker Seeking Employment'". TheWrap. Archived from the original on August 26, 2017. Retrieved August 25, 2017.

- ^ Fleming, Mike Jr. (May 17, 2014). "Cannes Update: Open Road & 'Nightcrawler': Je vous l'avais bien dit". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on August 25, 2017. Retrieved August 25, 2017.

- ^ Shea, Courtney (September 6, 2014). "Bill Murray on the dance floor is Friday night's TIFF FOMO moment to beat". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on October 27, 2016. Retrieved November 1, 2016.

- ^ Levine, Sydney (September 5, 2014). "The 34th Atlantic Film Festival announces Full Festival Program". IndieWire. Archived from the original on November 5, 2016. Retrieved November 1, 2016.

- ^ Yamato, Jen (August 27, 2014). "'Nightcrawler' To Close Fantastic Fest 2014; 'John Wick' Joins Lineup". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on November 5, 2016. Retrieved November 1, 2016.

- ^ Vivarelli, Nick (September 29, 2014). "Rome Film Fest Unveils New Concept Lineup Comprising Twenty Four World Preems". Variety. Archived from the original on November 5, 2016. Retrieved November 1, 2016.

- ^ "Jake Gyllenhaal's 'Nightcrawler' Moves to Halloween, Avoids Brad Pitt's 'Fury'". TheWrap. August 19, 2014. Archived from the original on December 23, 2016. Retrieved November 1, 2016.

- ^ "Release Schedule - February 2015". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on August 24, 2017. Retrieved August 24, 2017.

- ^ a b Spurlin, Thomas (February 10, 2015). "Nightcrawler (Blu-ray)". DVD Talk. Archived from the original on August 25, 2017. Retrieved August 24, 2017.

- ^ "Nightcrawler (2014) - DVD Sales". The Numbers. Archived from the original on August 20, 2016. Retrieved March 19, 2017.

- ^ a b Zeitchik, Steven (November 1, 2014). "Friday box office: 'Ouija' inches ahead of 'Nightcrawler'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on September 16, 2016. Retrieved September 6, 2016.

- ^ a b Subers, Ray (November 2, 2014). "Weekend Report: 'Nightcrawler,' 'Ouija' in Dead Heat Over Halloween". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on October 22, 2016. Retrieved September 6, 2016.

- ^ Subers, Ray (November 9, 2014). "Weekend Report: Disney's 'Big Hero 6' Eclipses Nolan's 'Interstellar'". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on June 9, 2016. Retrieved September 6, 2016.

- ^ Hipes, Patrick (December 3, 2014). "'Nightcrawler' Crawling Back Into Theaters In Awards Push". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on November 5, 2016. Retrieved November 1, 2016.

- ^ Grant, Charles (November 4, 2014). "Mr Turner makes a big impression at the UK box office". theguardian.com. Archived from the original on September 11, 2016. Retrieved September 6, 2016.

- ^ Grant, Charles (November 11, 2014). "Interstellar goes into orbit at UK box office with Mr Turner rising fast". theguardian.com. Archived from the original on September 11, 2016. Retrieved September 6, 2016.

- ^ "Nightcrawler (2014)". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on August 30, 2017. Retrieved April 8, 2024.

- ^ "Nightcrawler". Metacritic. Archived from the original on February 8, 2015. Retrieved February 7, 2015.

- ^ Bowles, Scott (November 3, 2014). "'Ouija' Wins Halloween Squeaker As Holdovers Guard Box Office Stash". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on August 24, 2017. Retrieved August 24, 2017.

- ^ Monk, Katherine (October 31, 2014). "Nightcrawler, reviewed: Jake Gyllenhaal's charming sociopath anchors tale of morality in the City of Angels". National Post. Archived from the original on December 26, 2014. Retrieved December 25, 2014.

- ^ Baker, Jeff (October 30, 2014). "'Nightcrawler' review: Jake Gyllenhaal is a violent sociopath who finds a rewarding career in TV news". oregonian.com. Archived from the original on December 26, 2014. Retrieved December 25, 2014.

- ^ Lemire, Christy (November 5, 2014). "Nightcrawler". ChristyLemire.com. Archived from the original on December 11, 2014. Retrieved December 23, 2014.

- ^ Orr, Christopher (October 31, 2014). "Nightcrawler: A Breakthrough for Jake Gyllenhaal". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on December 19, 2014. Retrieved December 23, 2014.

- ^ Sachs, Ben (October 29, 2014). "In Nightcrawler, if it bleeds, it leads". Chicago Reader. Archived from the original on December 27, 2014. Retrieved December 23, 2014.

- ^ Roeper, Richard (October 30, 2014). "'Nightcrawler': Jake Gyllenhaal a convincing creep, but gaffes spoil story". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on August 24, 2017. Retrieved August 24, 2017.

- ^ "2014 Favorites With Keith Uhlich (Part 1)". The Cinephiliacs. January 4, 2015. Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- ^ Hynes, David (February 2, 2017). "10 Best Movie Screenplays Since 2010". WhatCulture.com. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- ^ Han, Angie (January 15, 2015). "2015 Academy Awards Nominations". /Film. Archived from the original on October 27, 2016. Retrieved February 14, 2017.

- ^ "Bafta Film Awards 2015: Winners". BBC News. January 9, 2015. Archived from the original on October 27, 2016. Retrieved February 14, 2017.

- ^ "Critics Choice Awards Winners". Variety. January 15, 2015. Archived from the original on February 22, 2016. Retrieved February 14, 2017.

- ^ "Golden Globes 2015: The Winners". Rolling Stone. January 11, 2015. Archived from the original on August 7, 2016. Retrieved February 14, 2017.

- ^ Zuckerman, Esther (January 25, 2015). "SAG Awards 2015: The winners list". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on May 9, 2015. Retrieved February 14, 2017.

External links[edit]

- Nightcrawler at AllMovie

- Nightcrawler at IMDb

- 2014 films

- 2014 crime thriller films

- 2014 independent films

- 2010s satirical films

- 2014 psychological thriller films

- American crime thriller films

- American independent films

- American satirical films

- Bold Films films

- Films about photojournalists

- Films about murderers

- Films about television people

- Films directed by Dan Gilroy

- Films scored by James Newton Howard

- Films set in Los Angeles

- Films shot in California

- American neo-noir films

- Open Road Films films

- Films with screenplays by Dan Gilroy

- 2014 directorial debut films

- 2010s English-language films

- 2010s American films

- American psychological thriller films