THE ENVIRONMENTAL

FIRST LADY

Early Years

Mrs. Johnson was born Claudia Alta Taylor in the East Texas town of Karnack on December 22, 1912. Her father, Thomas Jefferson Taylor, was owner of a general store. Her mother, Minnie Pattillo Taylor, died when Claudia was five years old. Legend has it that a nursemaid said Claudia was "as purty as a lady bird;" the nickname stuck for life.

As a child, Lady Bird Johnson paddled in the dark bayous of Caddo Lake in East Texas, under ancient cypress trees decorated with Spanish moss. The sense of place that came from being close to the land never left her. She would devote much of her life to preserving it.

Mrs. Johnson graduated from Marshall High School in 1928 and attended Saint Mary's Episcopal School for Girls in Dallas from 1928 to 1930. She then entered The University of Texas at Austin, from which she graduated in 1934 with a Bachelor of Arts in history and journalism.

A very short clip from Mrs. Johnson's home movies. This 1943 footage was taken in a field of bluebonnets that would become the Mueller Airport, and now, the Mueller Austin neighborhood. Watch more home movies.

Pre-White House Years

Lady Bird Johnson met the tall, ambitious man whom she would marry – Lyndon Baines Johnson – when he was a Congressional secretary visiting Austin on official business. They were engaged just seven weeks after their first date and married in November 1934.

In 1943, Mrs. Johnson bought a failing low-power daytime-only Austin radio station with an inheritance from her mother. Armed with her journalism degree and a tireless work ethic, she took a hands-on ownership role, selling advertising, hiring staff and even cleaning floors. Over time, her Austin broadcasting company grew to include an AM and FM radio station and a television station, all bearing the same call letters: KTBC.

The family later expanded the LBJ holdings to stations in Waco and Corpus Christi and a cable television system. After selling the television station in 1972 and the cable system in the early '90s, the family grew their radio interests in Austin to include six stations. Mrs. Johnson stayed actively involved in the LBJ Holding Company well into her 80s.

The White House Years

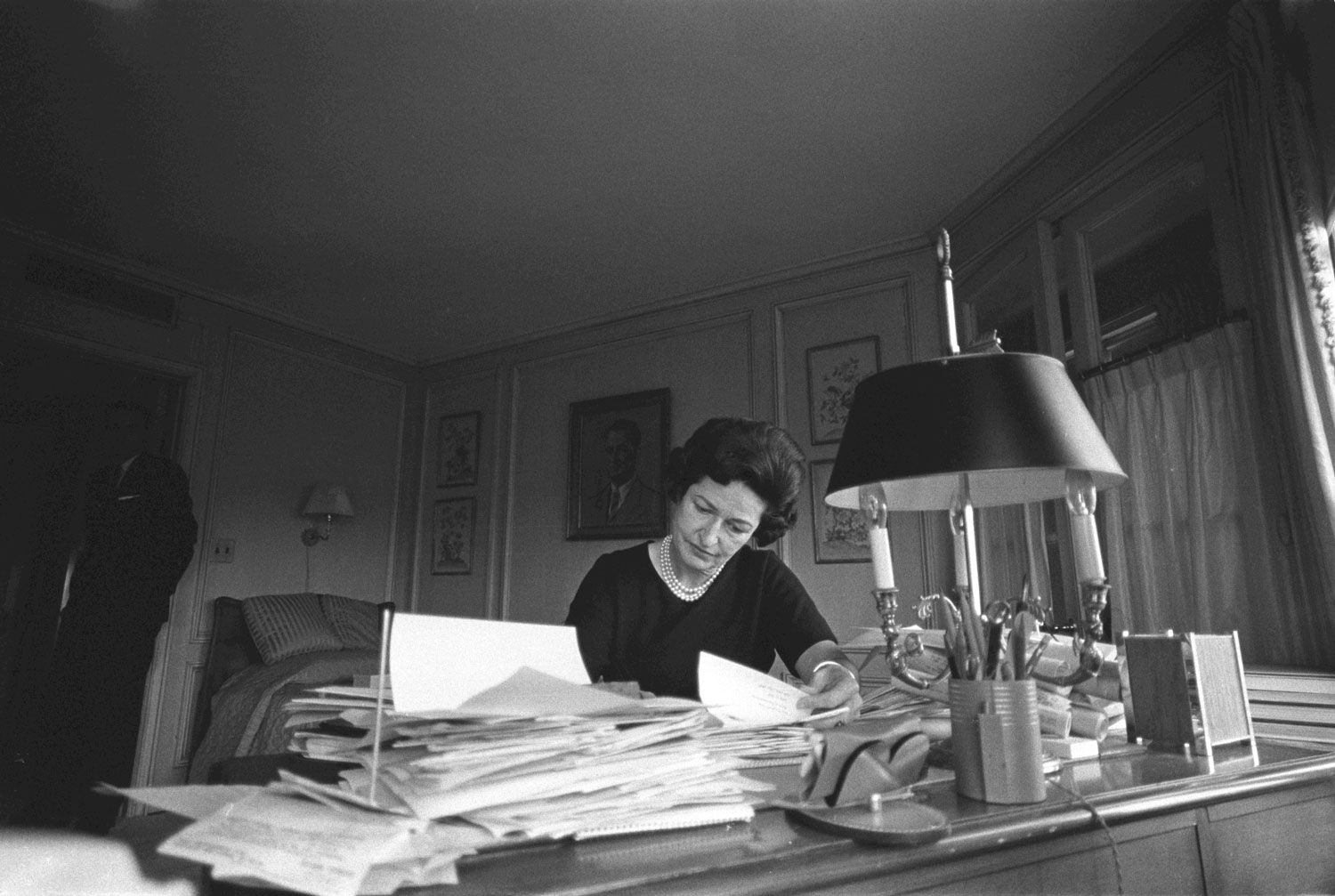

Lady Bird Johnson in her office. LBJ Library photo by Yoichi Okamoto.

Lady Bird Johnson stood by her husband on the fateful November day in 1963 on which Lyndon Johnson became the 36th President of the United States after the assassination of John Kennedy. Her official White House biography notes that her gracious personality and Texas hospitality did much to heal the pain of those dark days.

As she was growing up and later tending to the many duties as wife of a rising political star, Mrs. Johnson often noted the impact that natural beauty had on her life. But it wasn’t until she was First Lady of the nation that she was able to translate her love for the land into national policy. Once started, she amassed a lifetime of achievement as the Environmental First Lady.

She created a First Lady's Committee for a More Beautiful Capital and then expanded her program to include the entire nation. She was also highly involved in the President's war on poverty, focusing in particular on the Head Start project for preschool children.

Former Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall credits several trips to the American West, the Rocky Mountains and Utah with igniting Mrs. Johnson's interest in conservation. In 1964, when she visited Indian reservations and dedicated the Flaming Gorge Dam in Utah, she told audiences that natural beauty was their greatest resource and must be protected.

Right after the 1964 election, she decided that "the whole field of conservation and beautification" had the greatest appeal to her. Soon after that, she was urging her husband to see what could be done about junkyards along the nation's highways.

Beautification

Today, perhaps most people think of Lady Bird Johnson as the reason why we see wildflowers blooming along the nation's highways and fewer junkyards and billboards. The Beautification Act of 1965 was one tangible result of Mrs. Johnson's campaign for national beautification. Known as "Lady Bird's Bill" because of her active support, the legislation called for control of outdoor advertising, including removal of certain types of signs along the nation's Interstate system and the existing federal-aid primary system. It also required certain junkyards along Interstate or primary highways to be removed or screened and encouraged scenic enhancement and roadside development.

It is part of that legacy that today the Surface Transportation and Uniform Relocation Assistance Act of 1987 requires that at least 0.25 of 1 percent of funds expended for landscaping projects in the highway system be used to plant native flowers, plants and trees.

The term beautification concerned Mrs. Johnson, who feared it was "cosmetic" and "trivial." She emphasized that it meant much more-"clean water, clean air, clean roadsides, safe waste disposal and preservation of valued old landmarks as well as great parks and wilderness areas." Meg Greenwood, writing in the Reporter, noted the "deceptively sweet and simple-sounding name of 'beautification'."

Mrs. Johnson made it her mission to call attention to the natural beauty of the nation, and one of her most important efforts was in Washington, D.C., which was much in need of a facelift.

In 1964 Mrs. Johnson formed the Committee for a More Beautiful Capital, responding to Mary Lasker's suggestion that she make Washington, D.C., a "garden city" and a model for the rest of the nation. Soon afterward Mrs. Lasker, a philanthropist who lobbied for medical research as well as for natural beauty and Mrs. Johnson founded the Society for a More Beautiful National Capital, which received private donations for the project. The first planting took place on the mall where Mrs. Johnson planted pansies. She then planted azaleas and dogwood in the Triangle at Third and Independence Avenue and ended her first planting effort at a public housing project.

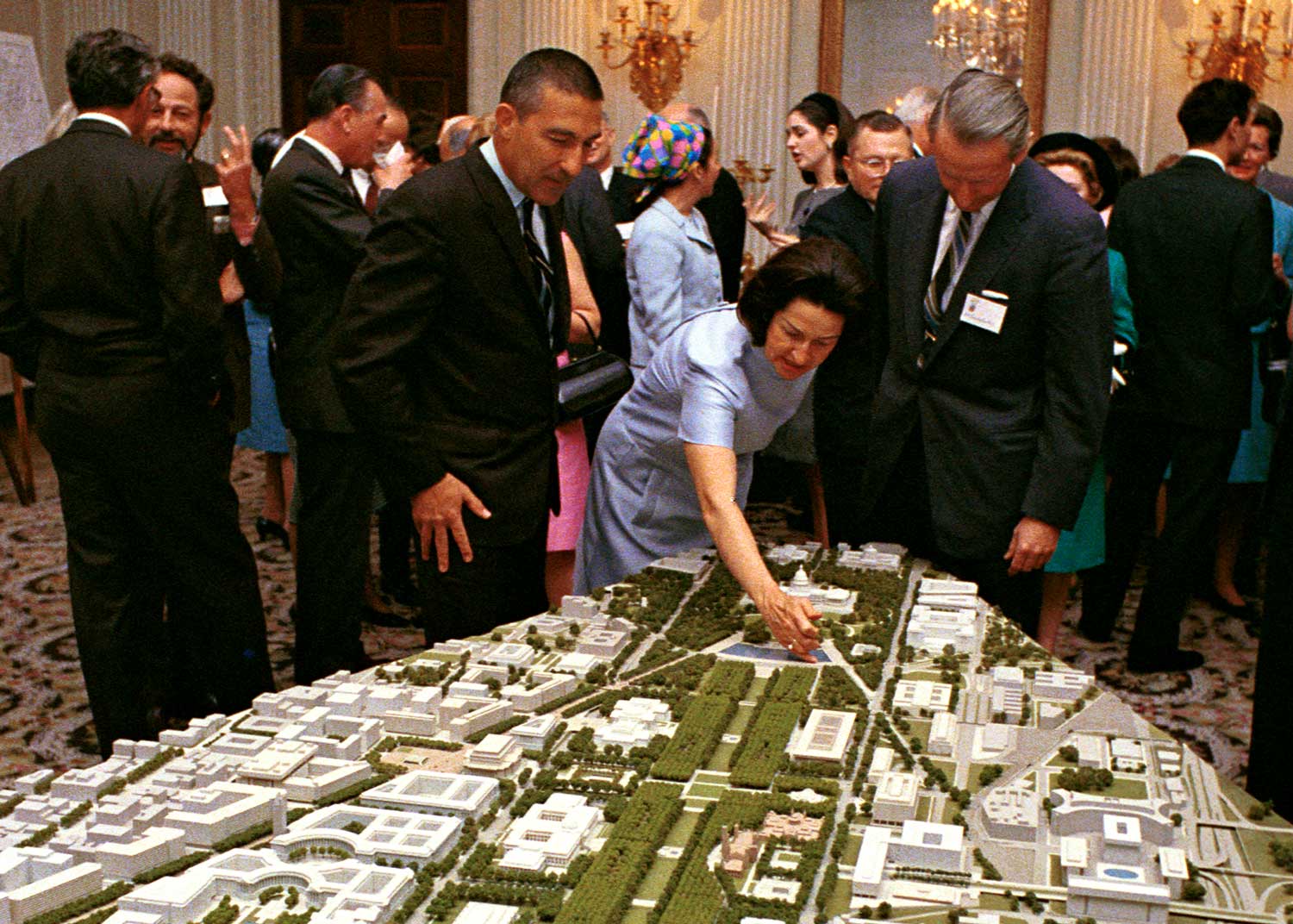

Foreground L-R: Sec. Stewart Udall, Lady Bird Johnson and Laurance Rockefeller look at an architectural model of the Washington, D.C. in 1967. LBJ Library photo by Robert Knudsen.

Mrs. Johnson enlisted a stellar team to attack the issue, including Nash Castro, White House liaison for the National Park Service, philanthropist Laurance S. Rockefeller, Kathleen Louchheim, an Assistant Secretary of State and leader among Democratic women, and many others.

Mrs. Johnson's view of this project went far beyond planting daffodil bulbs. She was concerned with pollution, urban decay, recreation, mental health, public transportation and the crime rate. The Committee agreed to plant flowers in triangle parks all over the city, to give awards for neighborhood beautification, and to press for the revitalization of Pennsylvania Avenue and the preservation of Lafayette Park. The Committee also generated enormous donations of cash and azaleas, cherry trees, daffodils, dogwood and other plants in evidence today in Washington's lovely parks and green spaces. Perhaps most importantly, Mrs. Johnson's effort prompted businesses and others to begin beautification efforts in low-income neighborhoods hidden from the much-visited tourist attractions.

One of her key efforts was an effort to clean up trash and control rats in the Shaw section of Washington. That developed into Project Pride, which enlisted Howard University students and high school students to clean up neighborhoods. Mrs. Johnson funded the project with a $7,000 grant from the Society for a More Beautiful Capital.

Later, Mrs. Johnson was a key player in the White House Conference on Natural Beauty that convened in May 1966, and was coordinated by Laurance S. Rockefeller. She opened the conference with a question: "Can a great democratic society generate the drive to plan, and having planned, execute projects of great natural beauty?" The conference sparked similar local conferences and added momentum to the national conservation movement.

One result was the President's Council on Recreation and Natural Beauty, chaired by Vice President Hubert Humphrey, another vehicle for spreading the conservation message and encouraging such local efforts as anti-litter campaigns.

President Johnson also issued a proclamation declaring 1967 a "Youth Natural Beauty and Conservation Year." The Johnsons opened the year with a press conference honoring youth leaders at the LBJ Ranch.

One method Mrs. Johnson employed in her beautification campaign was to call attention to important sites by visiting those places with the media in tow. She visited historic sites, national parks, and scenic areas, usually accompanied by Nash Castro of the National Park Service, a number of dignitaries and the media. Her nine beautification trips included Virginia historic places, the Hudson River in New York, Big Bend National Park and the California Redwoods, among others.

Mrs. Johnson's views, expressed in letters and conversations, had influence in preventing the construction of dams in the Grand Canyon and in creating Redwoods National Park.

That the Johnson Administration was the most active in conservation since the time of Theodore Roosevelt and Franklin D. Roosevelt is largely due to Mrs. Johnson. Among the major legislative initiatives were the Wilderness Act of 1964, the Land and Water Conservation Fund, the Wild and Scenic Rivers Program and many additions to the National Park system, a total of 200 laws relevant to the environment.

President Lyndon B. Johnson and Lady Bird Johnson walking through a field of flowers. LBJ Library photo by Frank Wolfe.

The President thanked his wife for her dedication on July 26, 1968, after signing the Department of the Interior Appropriations Bill. He presented her with 50 pens used to sign some 50 laws relating to conservation and beautification and a plaque that read: "To Lady Bird, who has inspired me and millions of Americans to try to preserve our land and beautify our nation. With love from Lyndon."

Just before President Johnson left office, Columbia Island in the Potomac River was renamed Lady Bird Johnson Park. Starting in 1969, she served on the Advisory Board on National Parks, Historic Sites, Buildings and Monuments.

Back in Texas

After leaving Washington, Mrs. Johnson focused her effort on Texas. She was the leading force behind Austin's beautiful hike and bike trail that winds more than 10 miles around the Town Lake portion of the Colorado River, graced with blooming native trees and plants. "She'll say she got on a moving train, but she had the leadership to say it could be a jewel," said Carolyn Curtis, a close family friend. "Now it is the meeting point of all of Austin…It brought in the Hyatt and the Four Seasons. She was the one with that vision."

For 20 years, starting in 1969, she encouraged the beautification of Texas highways by personally giving awards to the highway districts that used native Texas plants and scenery to the best advantage. Her focus was on the ecological advantages as well as the beauty of native plants – a passion that would lead her to create the National Wildflower Research Center in 1982 on the occasion of her 70th birthday.

Mrs. Johnson enlisted her friend, actress Helen Hayes, and made a personal contribution of $125,000 and 60 acres east of Austin to start the center, which grew into an organization of more than 13,000 members. The Center soon became a national leader in research, education and projects that encouraged the use of wildflowers.

Lady Bird Johnson spreads seeds on the site of the National Wildflower Research Center. LBJ Library photo by Frank Wolfe.

Several years later, Mrs. Johnson foresaw the need for a larger site and located a lovely 43-acre piece of land in the Hill Country of Southwest Austin on which to erect a permanent building. The new Center opened in 1995. In 1998, it was renamed the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. Now, with 279 acres, more than 650 plant species on display, and a fully developed education program for children and adults, the Wildflower Center's influence is strong across the nation.

Learn more about the Wildflower Center.

In an article in the Organization of American Historians' Magazine of History, Historian Rita G. Koman said, "Lady Bird Johnson's legacy was to legitimize environmental issues as a national priority. The attitudes and policies she advanced have shaped the conservation and preservation policies of the environmental movement since then."

Lewis L. Gould, University of Texas professor and author of Lady Bird Johnson and the Environmental Movement, wrote in his preface: "If a man in the 1960s had been involved with an environmental movement such as highway beautification, had changed the appearance of a major American city, had addressed the problems of black inner-city youth and had campaigned tirelessly to enhance national concern about natural beauty, no doubts would be raised that he was worthy of biographical and scholarly scrutiny. Lady Bird Johnson's accomplishments as a catalyst for environmental ideas during the 1960s and thereafter entitle her to an evaluation of what she tried to do and what she achieved."

Mrs. Johnson died at her home in Austin on July 11, 2007.

Explore More

Biographies and Videos about Lady Bird Johnson

The Wildflower Center Store has a wide selection of products about Lady Bird Johnson. All of your purchases from the Store benefit the research and educational programs at the Wildflower Center.

LBJ Presidential Library

In addition to a biography of Mrs. Johnson, the LBJ Presidential Library has an extensive collection of images and a section dedicated to the First Lady's Gallery in the museum.

Lyndon B. Johnson National Historical Park

Lyndon B. Johnson National Historical Park tells the story of our 36th President beginning with his ancestors until his final resting place on his beloved LBJ Ranch. This entire "circle of life" gives the visitor a unique perspective into one of America's most noteworthy citizens by providing the most complete picture of an American president.