A version of this piece originally appeared in Andrew Liptak’s Substack, Transfer Orbit.

On Friday, Twitter did something that it should have done years ago: It permanently banned President Donald Trump from the platform, citing “the risk of further incitement of violence” after a mob of supporters stormed the Capitol in Washington.

The president had used the platform for more than a decade, building up a massive following that would help propel him into the White House. Twitter has been his preferred megaphone in the last half-decade, and the company has certainly given him plenty of leeway in that time as he’s used it to get his messaging out.

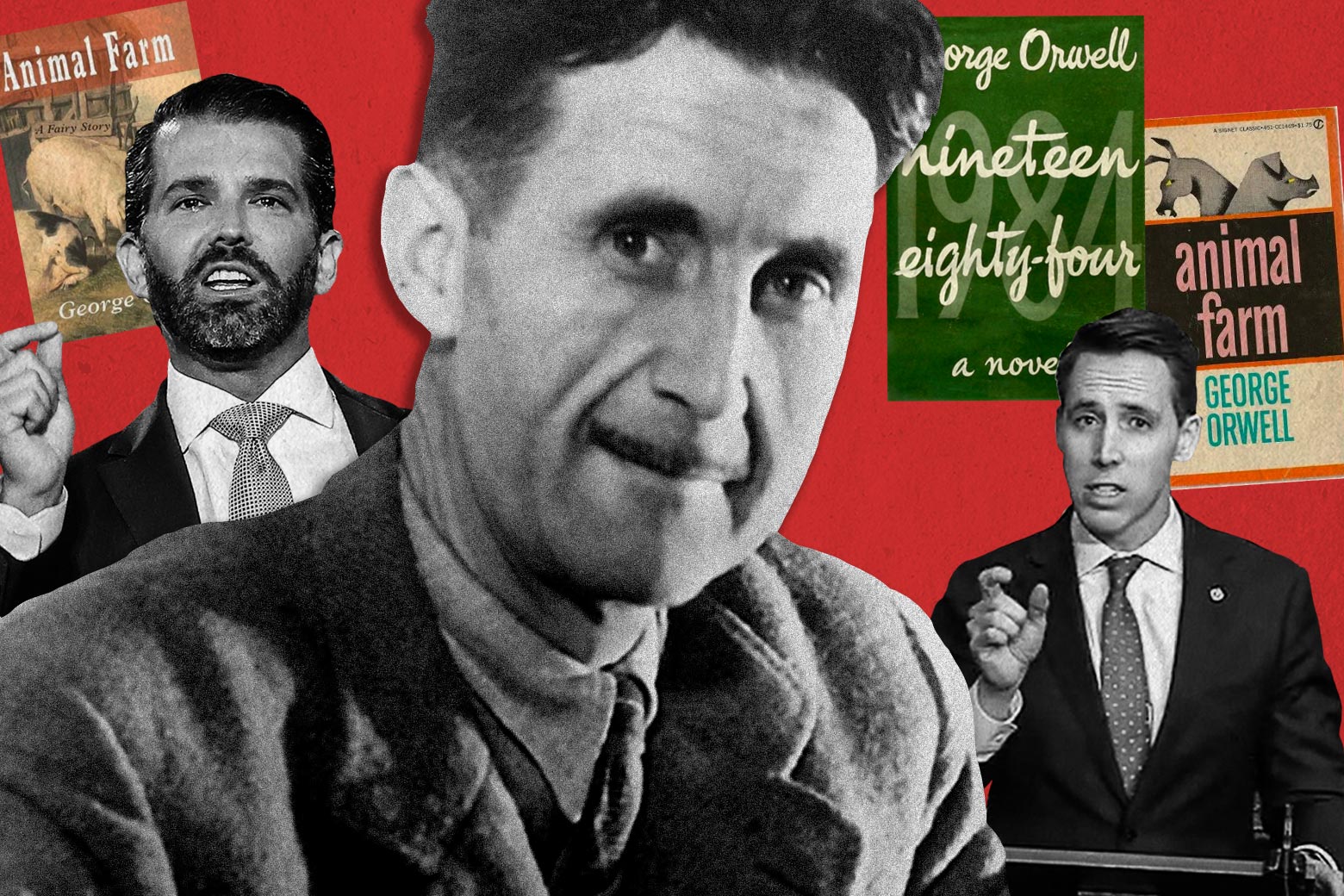

Since the perma-suspension came down—and even before it, as Twitter (and Facebook, Instagram, and other platforms) began to put warning or clarification labels on misleading posts—there’s been plenty of outrage from the right about how these tech firms are censoring them for their political beliefs. Notably, Trump’s son Donald Trump Jr. wrote (on Twitter!) that “we are living Orwell’s 1984. Free-speech no longer exists in America. It died with big tech and what’s left is only there for a chosen few.”

Others have raised similar arguments. Following the incident at the Capitol, publisher Simon & Schuster announced that it would cancel Missouri Sen. Josh Hawley’s upcoming book The Tyranny of Big Tech, citing his objections to the election certification. In a statement, Hawley again invoked the imagery of Orwell: “This could not be more Orwellian.”

Both cases certainly aren’t true: Trump has the entire White House press corps at his disposal, and with it the ability to put his message out via any number of venues. Hawley has plenty of options to see his book make it into the public, either through another publisher or some other method.

There have been other accusations as well: users expressing their alarm at how Twitter appeared to be suppressing a hashtag for the novel—they couldn’t use “#1984.” However, Twitter’s hashtags have never worked with just numbers.

All of these instances fit with something I’ve noticed in right-wing Twitter/bloggersphere since November: the invocation of Orwell. I’ve seen Orwellian or wrongthink or 1984 unironically floating around online as users decry this perceived persecution at the hands of big tech companies. The imagery and language of George Orwell’s novel 1984 has long been used as a rote stand-in descriptor for the right for the moments when they feel slighted, or as a way to point out a perceived overreach of power by the government (or, in these cases, private businesses).

And it’s equally clear that they don’t know what they’re talking about.

It’s easy to see why the idea of the novel itself (written by an avowed democratic socialist) holds particular appeal for American conservatives. The book is Orwell’s examination of totalitarian and dystopian societies, how they suppress and surveil free thought, people’s movements and opportunities, and ultimately create an alternate reality for their citizens.

Orwell isn’t the first to explore this topic: As the 20th century arrived, there came a moment when authors began to recognize the ways in which governments could use technology in harmful ways when mixed with ideology. Yevgeny Zamyatin wrote We in 1920, a response to the problems he saw in Russia at the time. There’s also Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, Katharine Burdekin’s Swastika Night (1937), Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451, and plenty of others that have examined this line of thought.*

The concern over a strong, central authority in America has been a historical wellspring of libertarian and right-wing thinking, and dystopian fiction’s predilection for the topic makes it an appealing canon for activists to turn to. Notably, William Pierce, author of the racist dystopian novel The Turner Diaries, invoked the threat of “Big Brother” as a motivating factor for his fictional terrorists.

Sympathetic political ideology is one connection, but there’s another, more ironic instance here: the use of language. 1984, critic Katharine M. Morsberger writes in her critical essay in Survey of Science Fiction Literature Volume 3, is concerned with how language works in society.

“Language and its significance is the dominant theme in Nineteen-Eighty Four. … In Newspeak, it is impossible to think certain thoughts because there are no longer words for them. History and literature are rewritten to conform to the Party’s view.”

Orwell’s works endure because of his focus on a central tenet of dystopian fiction: the control of language in shaping reality. Terms like Big Brother, doublethink, 2+2 = 5, or thoughtcrime are extremely effective, conveying their satirical definitions outside of the context of the book. They’re absurd terms, but that’s the point: They show how warped reality can become for them to be accepted on their face.

I spoke with a science fiction author and data scientist, Yudhanjaya Wijeratne, about this the other day, and he made an interesting observation about how language helps shape one’s worldview: In 1984, Orwell highlighted the efforts on the part of his fictional government to simplify languages down to very basic ideas to avoid free thought as a form of control reducing people’s abilities to express complicated thoughts and concepts.

Wijeratne noted that the right seems to be on a similar path: simplifying arguments and their associated language to effectively spread them to their followers. By contrast, he said, he’s seen the left go in the opposite direction: introducing more nuanced language or emphasizing a diversity of opinions or worldviews.

There’s an irony here: that the rhetoric invoking Orwell’s imagery is coming from a political movement that is essentially putting its head in the sand and denying actual reality. I’ve heard plenty of people talking about how it’s an established fact that climate change is a hoax, how the Democrats are secretly trafficking children, the left stole the election for Biden, or that the entirety of the political right is being silenced because of a cabal of tech companies conspiring against it.

And those beliefs are supported by a larger media ecosystem of TV networks, talk radio, alt-right blogs, and social media platforms, all of which have convinced a large segment of the population that reality isn’t really what it seems—and that it doesn’t matter. Remember: A prominent member of this party once championed the phrase “alternative facts” with a straight face.

Now that’s Orwellian.

Correction, Jan. 12, 2021: This piece originally misspelled Katharine Burdekin’s first and last name.

Future Tense is a partnership of Slate, New America, and Arizona State University that examines emerging technologies, public policy, and society.