John I, Margrave of Brandenburg

Last updated| John I | |

|---|---|

Monument to John I (sitting) and his brother Otto III in the Siegesallee in Berlin, by Max Baumbach. | |

| Margrave of Brandenburg | |

| Reign | 1220–1266 |

| Predecessor | Albert II |

| Successor | Otto III |

| Born | c. 1213 |

| Died | 4 April 1266 |

| Burial | Mariensee monastery |

| Spouse | Sophie of Denmark Brigitte of Saxony |

| Issue | John II, Margrave of Brandenburg-Stendal Otto IV, Margrave of Brandenburg-Stendal Conrad, Margrave of Brandenburg-Stendal Eric, Archbishop of Magdeburg Helene, Margravine of Landsberg Hermann, Bishop of Havelberg Agnes, Queen of Denmark Henry I, Margrave of Brandenburg-Stendal Matilda, Duchess of Pomerania Albert of Brandenburg |

| House | House of Ascania |

| Father | Albert II, Margrave of Brandenburg |

| Mother | Matilda of Lusatia |

John I, Margrave of Brandenburg ( c. 1213– 4 April 1266) was from 1220 until his death Margrave of Brandenburg, jointly with his brother Otto III "the Pious".

Contents

- Life

- Regency and guardianship

- Domestic policies

- Developing the country

- Development in the Berlin area

- Inheritance and descendants

- Johannine and Ottonian line

- Marriage and issue

- Double statue of the brothers at the Siegesallee

- Ancestry

- References

- Primary references

- Secondary references

- Footnotes

The reign of these two Ascanian Margraves was characterized by an expansion of the Margraviate, which annexed the remaining parts of Teltow and Barnim, the Uckermark, the Lordship of Stargard, the Lubusz Land and parts of the Neumark east of the Oder. They consolidated the position of Brandenburg within the Holy Roman Empire, which was reflected in the fact that in 1256, Otto III was a candidate to be elected King of the Germans. They founded several cities and developed the twin cities of Cölln and Berlin. They expanded the Ascanian castle in nearby Spandau and made it their preferred residence.

Before their death, they divided the Margraviate in a Johannine and an Ottonian part. The Ascanians were traditionally buried in the Lehnin Abbey in the Ottonian part of the country. In 1258, they founded a Cistercian monastery named Mariensee, where members of the Johannine line could be buried. In 1266, they changed their mind and founded a second monastery, named Chorin, 8 km southwest of Mariensee. John was initially buried at Mariensee; his body was moved to Chorin in 1273.

After the Ottonian line died out in 1317, John I's grandson Waldemar reunited the Margraviate.

Life

Regency and guardianship

John was the elder son of Albert II of the Brandenburg line of the House of Ascania and Mechthild (Matilda), the daughter of Margrave Conrad II of Lusatia, a junior line of the House of Wettin. Since both John and his two years younger brother Otto III were minors when their father died in 1220, Emperor Frederick II transferred the regency to Archbishop Albert I of Magdeburg. The guardianship was taken up by the children's first cousin once removed, Count Henry I of Anhalt, the older brother of Duke Albert I of Saxony, a cousin of Albert II. As the sons of Duke Bernhard III of Saxony, they were the closest relatives, and Henry had the older rights.

In 1221, their mother, Countess Matilda, purchased the regency from the Archbishop of Magdeburg for 1900 silver Marks and then ruled jointly with Henry I. [1] The Archbishop of Magdeburg then travelled to Italy, to visit Emperor Frederick II and Duke Albert I of Saxony attempted to grab power in Brandenburg, causing a rift with his brother Henry I. The Saxon attack presented an opportunity for Count Palatine Henry V to get involved. Emperor Frederick II managed to prevent a feud, urging them to keep the peace.

After Matilda died in 1225, the brothers ruled the Margraviate of Brandenburg jointly. John I was about twelve years old at the time, and Otto III was ten. They were knighted on 11 May 1231 in Brandenburg an der Havel and this is generally taken as the beginning of their reign. [2] [3]

Domestic policies

After the death of Count Henry of Brunswick-Lüneburg in 1227, the brothers supported his nephew, their brother-in-law Otto the Child, who was only able to prevail against Hohenstaufen claims and its vassals by force of arms. In 1229, there was a feud with former regent Archbishop Albert, which ended peacefully. Like their former opponents and defenders, they appeared at the Diet of Mainz in 1235, where the Public Peace of Mainz was proclaimed.

After the dispute over the kingship between Conrad IV and Henry Raspe the brothers recognized William II of Holland as king in 1251. They first exercised Brandenburg's electoral privilege in 1257, when they voted for king Alfonso X of Castile. Although Alfonso was not elected, the fact that they were able to vote illustrates the growing importance of Brandenburg, which had been founded only a century earlier, in 1157, by Albert the Bear. When John and Otto came to power, Brandenburg was considered an insignificant little principality on the eastern border. By the 1230s, the Margraves of Brandenburg had definitely gained the heritable post of Imperial Chamberlain and the indisputable right to vote in the election of the King of the Germans. [4]

Developing the country

John I and his brother Otto III developed the territory of their margraviate and expanded market towns and castles, including Spandau, Cölln and Prenzlau into towns and centers of commerce. They also expanded Frankfurt an der Oder and John I awarded it city status in 1253.

The Teltow War and the Treaty of Landin

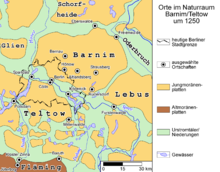

Between 1230 and 1245, Brandenburg acquired the remaining part of Barnim and the southern Uckermark up to the Welse river. On 20 June 1236, the Margraviate acquired the Lordships of Stargard, Beseritz and Wustrow by the Treaty of Kremmen from Duke Wartislaw III of Pomerania. Later that year, the brothers initiated the construction of Stargard Castle, to secure the northernmost part of their territory.

From 1239 to 1245, the brothers fought the Teltow War against the Margraves of Meissen of the House of Wettin. At stake was a Slavic castle at Köpenick, a former headquarters of the Sprewanen tribe, located at the confluence of the Spree and Dahme rivers, at the time, it was just east of Berlin; today it is part of the city. It dominated the Barnim and Teltow areas. In 1245, the brothers managed to take both castle a Köpenick and a fortress at Mittenwalde. From this base, they could expand further to the east. In 1249, they acquired the Lubusz Land and reached the river Oder.

In 1250, the brothers closed the Treaty of Landin with the Dukes of Pomerania. Under this treaty, they received the northern part of the Uckermark (terra uckra), north of the Welse river and the districts of Randow and Löcknitz, in exchange for the half of the Lordship of Wolgast that John I had received as dowry from King Waldemar II of Denmark when he married his first wife, Sophia. This treaty is considered the birth of the Uckermark as a part of Brandenburg. [5]

Policies to stabilize the Neumark

During the first third of the 13th century German settlers were recruited by Duke Leszek I the White to settle the Neumark. After he died in 1227, the Polish central government collapsed, allowing the Margraves of Brandenburg to expand eastwards. They acquired land east of the Oder and expanded their domain further east to the river Drawa and north to the river Persante. In 1257, John I founded the town of Landsberg (now called Gorzów Wielkopolski) as an alternative river crossing across the Warta, competing with the crossing in the Polish town of Santok, detracting from the considerable revenues Santok made from foreign trade (custom duties, fees from the market operation and storage fees), similar to the way Berlin had been founded to compete with Köpenick. In 1261, the Margraves purchased Myślibórz (German : Soldin) from the Knights Templar and began developing the town to their power center in the Neumark.

To stabilize their new possessions, the Margraves used the tried and tested Ascanian policy of founding monasteries and settlements. As early as 1230, they supported the Polish Count Dionysius Bronisius when he founded the Cistercian Paradies Monastery near Międzyrzecz (Meseritz) as a filiation of the monastery at Lehnin. Their cooperation with the Polish count provided border security against Pomerania and prepared the economy of the area for integration into the Neumark. Among the settlers in the Neumark was the von Sydow family, who were later ennobled. the small town of Cedynia (Zehden; today in the Polish Voivodeship of West Pomerania) was enfeoffed to the noble von Jagow family.

The historian Stefan Warnatsch has summarized this development and the attempts of the Ascanians to gain access to the Baltic Sea from the middle Oder and the Uckermark as follows: The great success of the territorial expansion in the 13th century was largely due to the great-grandsons of Albert the Bear [...]. The design of their reign reached much further spatially and conceptually then that of their predecessors. [6] According to Lutz Partenheimer: [around 1250], the Ascanians had pushed back their competitors from Magdeburg, Wettin, Mecklenburg, Pomerania, Poland and the smaller competitors on all fronts. [4] However, John I and Otto III failed to produce the strategically important connection to the Baltic Sea.

Development in the Berlin area

The development of the Berlin area is closely related to the other policies of the two Margraves. The two founding cities of Berlin (Cölln and Berlin) were founded relatively late. The settlements began around 1170 and achieved city status around 1240. [7] Other settlement in the area, such as Spandau and Köpenick, date back to the Slavic period (from about 720) and these naturally had a greater strategic and political importance than the young merchant towns Cölln and Berlin. For a long time the border between the territories of the Slavic tribes Hevelli and Sprewanen crossed straight through the area of today's Berlin. Around 1130, Spandau was an eastern outpost of the Hevelli under Pribislav. When Pribilav died in 1150, Spandau fell to Brandenburg under the terms of an inheritance treaty between Pribislav and Albert the Bear. Brandenburg did not acquire Köpenick until 1245.

Residence at Spandau

In 1229, the Margraves of Brandenburg lost a battle against their former guardian, the archbishop of Magdeburg at the Plauer See, close to their residence in Brandenburg an der Havel. The escaped to the fortress at Spandau. In the following years, the brothers made Spandau their preferred residence, next to Tangermünde in the Altmark. Between 1232 and 1266, seventeen stays at Spandau have been documented, more than at any other town. [8]

Albert the Bear probably expanded the fortress island at Spandau eastwards before or shortly after his victory against a certain Jaxa (this was probably Jaxa of Köpenick) in 1157. Towards the end of the 12th century, the Ascanians moved the fortress about a kilometer to the North, to the location of today's Spandau Citadel, probably because of a rising ground water table. The presence of an Ascanian fortress on this site in 1197 has been established. [9] John I and Otto III expanded the fortress and promoted the civitas in the adjacent settlement. They gave it city rights in 1232 or earlier. They founded the Benedictine nunnery of St. Mary in 1239. The Nonnendammallee, one of the oldest streets in Berlin and as Nonnendamm part of a trade route as early as the 13th century, is still a reminder of the former nunnery [10]

Expansion of Cölln and Berlin

According to the current state of research, no evidence has been found that a Slavic settlement existed in the area around the twin towns of Berlin and Cölln. [11] The ford across the largely swampy Berlin Glacial Valley gained importance during the Slavic-German transition period, when John I and Otto III settled the sparsely populated plateaus of Teltow and Barnim with local Slavs and German immigrants.

According to Adriaan von Müller, the strategic importance of Cölln and Berlin, and the reason for the foundation was probably to form a counterweight to Köpenick, a secure trading hub held by the Wettin (dynasty) with its own trade roues to the north and east. The broad ford across two or even three river arms away could best be protected by fortified settlements on both river banks. The Margraves protected the route to Halle across the northwestern Teltow plateau by a chain of Templar villages: Marienfelde, Mariendorf, Rixdorf and Tempelhof. After the Ascanians defeated the Wettins in the Teltow War of 1245, the importance of Köpenick decreased, took an increasingly central position in the developing trading network. [12]

According to Winfried Schich, we can assume the Berlin and Cölln owe their development as urban settlements to the structural changes in this area due to the expansion during the High Middle Ages, which led both to a denser population and a reorganization of long-distance trade routes. [...] The diluvial plateaus of Teltow and Barnim with their heavy and relatively fertile soils, were systematically settled and put under the plow during the reign of Margraves John I and Otto III. [13] During the first phase of settlement, the lowland areas along the river with their lighter soils seem to have been the preferred places of settlement.

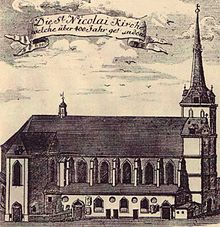

According to the Chronica Marchionum Brandenburgensium of 1280, Berlin and other places were built' (exstruxerunt) by John I and Otto III. Since their reign had started in 1225, the period around 1230 is considered the founding period of Berlin. Recent archeological research has uncovered evidence of late 12th century market towns in both Cölln and Berlin. Ninety graves were excavated in the St. Nicholas Church, the oldest building in Berlin, with foundations dated 1220-1230 and some of these graves could also be from the late 12th century. This implies that the two Margraves did not actually found the cities of Cölln and Berlin, although they did play a decisive rôle in the early expansion of the cities. [14]

Among the privileges granted to the two cities by the Margraves were Brandenburg Law (including absence of tolls, free exercise of trade and commerce, hereditary property rights) and in particular the staple right, [15] which gave Cölln and Berlin an economic advantage of Spandau and Köpenick. The Margraves gave the Mirica, the Cölln Moor, with all usage rights to the citizens of Cölln. The connection of the Margraves with Berlin is also evidenced by their choice of Hermann von Langele as their confessor. This Hermann von Langele was the first known member of the Franciscan convent at Berlin. He is mentioned as a witness in a deed issued by the Margrave in Spandau in 1257. [16]

Inheritance and descendants

The joint rule of the Margraves ended in 1258 with a division of their territory. A cleverly managed division and continued consensual policy prevented the Margraviate from falling apart. The preparations for the reorganization may have begun in 1250, when the Uckermark was acquired, but no later than 1255, when John I married Jutta (Brigitte), the daughter of Duke Albert I of Saxony-Wittenberg. [17]

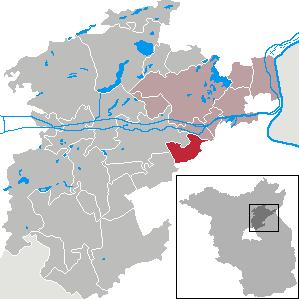

Johannine and Ottonian line

Chorin Abbey - Grave laying and power politics

The politics of marriage and 1258 consummated division of the state government led to the joint foundation of the monastery of Mariensee on a former island in the Parsteiner See lake on the northeastern edge of today's Barnim. Until then, deceased Margraves of Brandenburg had been buried at Lehnin Abbey, in the Ottonian part of the Margraviate. The monastery of Mariensee was meant to provide the Johannine line with a burial place of their own. Construction of the monastery began in 1258 with monks from Lehnin. Even before Marinesee was completed in 1273, a decision was made to move to a new location approximately five miles to the southwest with the new name Chorin Abbey. When John I died in 1266, he was initially buried at Mariensee. In 1273, his body was moved to Chorin Abbey. [18] It appears that in 1266, John I arranged for the monastery to move and that he donated rich gifts to the new Chorin Abbey, including the village of Parstein. His sons later confirmed these donations for the benefit of their father's soul and their own. [19]

As with all monastery founded by the Ascanians, political and economic considerations played an important rôle, alongside the pastoral aspects. A Slavic circular rampart existed on the island, to the west of the monastery. John I and Otto III probably used this rampart as a castle against their Pomeranian competitors. The monastery was meant to provide central and administrative functions. "Both the foundation itself and the location in a regional centre 'across' the trade route [...] in a populated area are to be interpreted as the result of political calculations". [20]

Dividing the Margraviate

When the Margraviate was divided, John I received Stendal and the Altmark, which was considered the "cradle" of Brandenburg, and would remain a part until 1806. He also received the Havelland and the Uckermark. His brother Otto III received Spandau, Salzwedel, Barnim, the Lubusz Land and Stargard. [21] The most important factors in this division were revenue and the number of vassals; geographical factors played only a subordinate rôle. [22] Their successors as Margraves of Brandenburg, Otto IV "with the Arrow", Waldemar "the Great" and Henry II "the Child" all stem from the Johannine line. Otto's sons and grandsons and John's younger sons also styled themselves "Margrave of Brandenburg" and as such co-signed official document — for example, John's sons John II and Conrad so-signed in 1273 the decision to move Mariensee monastery to Chorin — however, they remained "co-regents".

The Ottonian line died out in 1317 with the death of Margrave John V in Spandau, so that Brandenburg was reunited under Waldemar the Great. The Johannine line died out only three years later, with the death of Henry the Child in 1320, ending Ascanian rule in Brandenburg. In 1290, nineteen Margraves of the two lines had gathered on a hill near Rathenow; in 1318 only two Margraves were left alive: Waldemar and Henry the Child. [23] The last Ascanian in Brandenburg, the eleven-year-old Henry the Child, only played a minor rôle and was already at the mercy of the various houses trying to grab power in the upcoming power vacuum.

Marriage and issue

In 1230, John I married Sophie of Denmark (1217–1247), daughter of King Valdemar II of Denmark and Berengaria of Portugal. With her, he had the following children:

- John II of Brandenburg (1237(?)–1281), Margrave of Brandenburg as co-ruler.

- Otto IV of Brandenburg (c. 1238–1308), Margrave of Brandenburg.

- Conrad I of Brandenburg (c. 1240–1304), Margrave of Brandenburg as co-regent, the father of Waldemar, the last Ascanian Margrave of Brandenburg.

- Eric of Brandenburg (c. 1242–1295), Archbishop of Magdeburg from 1283 to 1295.

- Helene of Brandenburg (1241 or 1242 – 1304), married in 1258 to Margrave Dietrich of Landsberg (1242–1285).

- Hermann of Brandenburg (died: probably 1291), Bishop of Havelberg from 1290 onward.

In 1255, John I married Brigitte Jutta of Saxony, the daughter of Albert I, Duke of Saxony and Agnes of Austria (1206–1226). With her, he had the following children:

- Agnes of Brandenburg (after 1255 – 1304), married firstly in 1273 to King Erik V of Denmark (1249–1286), and secondly in 1293 to Gerhard II, Count of Holstein-Plön (1254–1312).

- Henry I of Brandenburg, "Lackland" (1256–1318), Margrave of Brandenburg and Landsberg.

- Matilda of Brandenburg (died: before 1309), married to Bogislaw IV, Duke of Pomerania (1258–1309).

- Albert of Brandenburg (c. 1258–1290)

John I held King Eric V prisoner from 1262 to 1264. In 1273, the King of Denmark married John's daughter, Agnes of Brandenburg.

After John's death in 1266, his brother Otto III ruled Brandenburg alone. After Otto's death in 1267, John's son, Otto IV, took over as the senior Margrave.

Double statue of the brothers at the Siegesallee

The double statue depicted on the left stood in the Siegesallee in the Großer Tiergarten in Berlin. The Siegesallee was a grand boulevard commissioned by Emperor Wilhelm II in 1895 with statues illustrating the history of Brandenburg and Prussia. Between 1895 and 1901, 27 sculptors led by Reinhold Begas created 32 statues of Prussian and Brandenburg rulers, each 2.75 high. Each statue was flanked by two smaller busts representing people who had played an important rôle in the life of the historic ruler.

The central statue in group 5 was the double statue of John and Otto. On the left was a bust of provost Simeon of Cölln, who was a witness, on 28 October 1237, together with bishop Gernand of Brandenburg, of the oldest deed in which Cölln is mentioned. [24] On the right was a bust of Marsilius de Berlin, the first recorded mayor ( Schultheiß ) of Berlin. He was simultaneously mayor of Cölln. [25]

The choice of the secular and ecclesiastical leaders of Berlin and Cölln as flanking characters for John and Otto underscores the pivotal rôle the city of Berlin played in the lives of the Margraves in the opinion of Reinhold Koser, the historian who did the research for the Siegesallee. Koser regarded the founding and development of the city as the Margrave's most important policy, more so than the expansion the principality and the founding of the monastery. he was also impressed by the consensus which characterised their joint rule, as presented in the Chronicle of 1280. According to Koser, the sculptor Max Baumbach was responsible for the decision to make the founding of Berlin the central theme of the double statue, rather than the expansion or the founding of the monastery.

John I depicted sitting on a stone, with the city charter of Berlin and Cölln spread across his knees. The younger Otto III stand beside him, pointing to the deed with one hand, while his other arm rests on a spear. The outstretched arms and bowed head suggest the brothers' protection and promotion of the twin cities. The fact that the two young men are depicted as mature men was seen by Koser as legitimized by the right of artistic freedom. Two adolescents would not have been able to adequately express the founding of a future world city, from the perspective of the late 19th century interpretation of history. [26]

The overall architecture of the statue group maintains a romanticism style. According to Uta Lehnert, the two eagles show characteristics of the Jugendstil. [26]

Ancestry

| Ancestors of John I, Margrave of Brandenburg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Related Research Articles

Prenzlau is a town in Brandenburg, Germany, the administrative seat of Uckermark District. It is also the centre of the historic Uckermark region.

Köpenick is a historic town and locality (Ortsteil) in Berlin, situated at the confluence of the rivers Dahme and Spree in the south-east of the German capital. It was formerly known as Copanic and then Cöpenick, only officially adopting the current spelling in 1931. It is also known for the famous imposter Hauptmann von Köpenick.

The Northern March or North March was created out of the division of the vast Marca Geronis in 965. It initially comprised the northern third of the Marca and was part of the territorial organisation of areas conquered from the Wends. A Lutician rebellion in 983 reversed German control over the region until the establishment of the March of Brandenburg by Albert the Bear in the 12th century.

Choszczno(listen) is a town in West Pomeranian Voivodeship, Poland. As of December 2021, the town has a population of 14,831. The town is in a marshy district between the river Stobnica and Klukom lake, 32 kilometres (20 mi) southeast of Stargard and on the main railway line between Szczecin and Poznań. Besides the Gothic church, there are a number of historical buildings from the 19th century industrial period namely, a gasification plant and a water pressure tower which dominates the town's skyline.

Kloster Lehnin, or just Lehnin, is a municipality in the German state of Brandenburg. It lies about 24 km (15 mi) west-south-west of Potsdam.

Lehnin Abbey is a former Cistercian monastery in Lehnin in Brandenburg, Germany. Founded in 1180 and secularized during the Protestant Reformation in 1542, it has accommodated the Luise-Henrietten-Stift, a Protestant deaconesses' house since 1911. The foundation of the monastery in the newly established Margraviate of Brandenburg was an important step in the high medieval German Ostsiedlung; today the extended Romanesque and Gothic brickstone buildings, largely restored in the 1870s, are a significant part of Brandenburg's cultural heritage.

The Diocese of Lebus is a former diocese of the Catholic Church. It was erected in 1125 and suppressed in 1598. The Bishop of Lebus was also, ex officio, the ruler of a lordship that was coextensive with the territory of the diocese. The geographic remit included areas that are today part of the land of Brandenburg in Germany and the Province of Lubusz in Poland. It included areas on both sides of the Oder River around the town of Lebus. The cathedral was built on the castle hill in Lubusz and was dedicated to St Adalbert of Prague. Later, the seat moved to Górzyca, back to Lebus and finally to Fürstenwalde on the River Spree.

The Margraviate of Brandenburg was a major principality of the Holy Roman Empire from 1157 to 1806 that played a pivotal role in the history of Germany and Central Europe.

Otto I was the second Margrave of Brandenburg, from 1170 until his death.

Hohenfinow is a municipality in the Barnim district in Brandenburg, Germany. It is part of the Amt Amt Britz-Chorin-Oderberg.

The Uckermark is a historical region in northeastern Germany, currently straddles the Uckermark District of Brandenburg and the Vorpommern-Greifswald District of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern. Its traditional capital is Prenzlau.

The Treaty of Landin was signed in Landin, Germany in 1250 between Barnim I of Pomerania-Stettin, the Ascanian margraves Johann I and Otto III of Brandenburg. Barnim I was accepted as co-ruler of Wartislaw III of Pomerania-Demmin by the Margraviate of Brandenburg, thereby hindering Brandenburg's succession in Pomerania-Demmin as was ruled out in the 1236 Treaty of Kremmen. Instead of the margraves, Barnim I integrated what was left of Pomerania-Demmin, after the territorial losses of 1236 into his Stettin-based duchy. The terra Wolgast within the Duchy of Pomerania, which was to be inherited by the Margraves, was exchanged for Pomeranian-held northern parts of the Uckermark. Barnim also accepted to be a Brandenburgian vassal.

Pomerania during the High Middle Ages covers the history of Pomerania in the 12th and 13th centuries.

Pomerania during the Late Middle Ages covers the history of Pomerania in the 14th and 15th centuries.

Starting in the 12th century, the Margraviate, later Electorate, of Brandenburg was in conflict with the neighboring Duchy of Pomerania over frontier territories claimed by them both, and over the status of the Pomeranian duchy, which Brandenburg claimed as a fief, whereas Pomerania claimed Imperial immediacy. The conflict frequently turned into open war, and despite occasional success, none of the parties prevailed permanently until the House of Pomerania died out in 1637. Brandenburg would by then have naturally have prevailed, but this was hindered by the contemporary Swedish occupation of Pomerania, and the conflict continued between Sweden and Brandenburg-Prussia until 1815, when Prussia incorporated Swedish Pomerania into her Province of Pomerania.

Albert II was a member of the House of Ascania who ruled as the margrave of Brandenburg from 1205 until his death in 1220.

The Barnim Plateau is a plateau which is occupied by the northeastern parts of Berlin and the surrounding federal state of Brandenburg in Germany.

Otto III, nicknamed the pious was Margrave of Brandenburg jointly with his elder brother John I until John died in 1266. Otto III then ruled alone, until his death, the following year.

John II, Margrave of Brandenburg-Stendal was co-ruler of Brandenburg with his brother Otto "with the arrow" from 1266 until his death. He also used the title Lord of Krossen, after a town in the Neumark.

The Teltow and Magdeburg Wars were fought between 1239 and 1245 over possession of Barnim and Teltow in the present-day federal German state of Brandenburg. They took place in the 13th century during the course of the Eastern German Expansion. The opposing sides during the armed conflict, which took place on two fronts simultaneously, were:

References

Primary references

- Heinrici de Antwerpe: Can. Brandenburg., Tractatus de urbe Brandenburg, edited and elucidated by Georg Sello, in: 22. Jahresbericht des Altmärkischen Vereins für vaterländische Geschichte und Industrie zu Salzwedel, Magdeburg, 1888, issue 1, p. 3-35, internet version by Tilo Köhn with transcriptions and translation.

- Chronica Marchionum Brandenburgensium, ed. G. Sello, FBPrG I, 1888.

- Schreckenbach, Bibliogr. zur Gesch. der Mark Brandenburg, vols. 1–5, Publications of the State Archive at Potsdam, vol. 8 ff, Böhlau, Cologne, 1970–1986

Secondary references

- Tilo Köhn (publisher): Brandenburg, Anhalt und Thüringen im Mittelalter. Askanier und Ludowinger beim Aufbau fürstlicher Territorialherrschaften, Böhlau, Cologne, Weimar and Vienna, 1997, ISBN 3-412-02497-X

- Helmut Assing: Die frühen Askanier und ihre Frauen, Kulturstiftung Bernburg, 2002, ISBN 3-9805532-9-9

- Wolfgang Erdmann: Zisterzienser-Abtei Chorin. Geschichte, Architektur, Kult und Frömmigkeit, Fürsten-Anspruch und -Selbstdarstellung, klösterliches Wirtschaften sowie Wechselwirkungen zur mittelalterlichen Umwelt, with contributions by Gisela Gooß, Manfred Krause and Gunther Nisch, with extensive bibliography, in the series Die Blauen Bücher, Königstein im Taunus, 1994, ISBN 3-7845-0352-7

- Felix Escher: Der Wandel der Residenzfunktion. Zum Verhältnis Spandau – Berlin. Das markgräfliche Hoflager in askanischer Zeit, in: Wolfgang Ribbe (ed.): Slawenburg, Landesfestung, Industriezentrum. Untersuchungen zur Geschichte von Stadt und Bezirk Spandau, Colloqium-Verlag, Berlin, 1983, ISBN 3-7678-0593-6

- Uta Lehnert: Der Kaiser und die Siegesallee. Réclame Royale, Dietrich Reimer Verlag, Berlin, 1998, ISBN 3-496-01189-0

- Lyon, Jonathan R. (2013). Princely Brothers and Sisters: The Sibling Bond in German Politics, 1100-1250. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0801451300.

- Uwe Michas: Die Eroberung und Besiedlung Nordostbrandenburgs, in the series: Entdeckungen entlang der Märkischen Eiszeitstraße, vol. 7, Gesellschaft zur Erforschung und Förderung der märkischen Eiszeitstraße (ed.), Eberswalde, 2003, ISSN 0340-3718.

- Adriaan von Müller: Gesicherte Spuren. Aus der frühen Vergangenheit der Mark Brandenburg, Bruno Hessling Verlag, Berlin, 1972, ISBN 3-7769-0132-2

- Lutz Partenheimer: Albrecht der Bär – Gründer der Mark Brandenburg und des Fürstentums Anhalt, Böhlau Verlag, Cologne, 2001, ISBN 3-412-16302-3

- Jörg Rogge: Die Wettiner, Thorbecke Verlag, Stuttgart, 2005, ISBN 3-7995-0151-7

- Winfried Schich: Das mittelalterliche Berlin (1237–1411), in: Wolfgang Ribbe (ed.): Veröffentlichung der Historischen Kommission zu Berlin: Geschichte Berlins, vol. 1, Verlag C.H. Beck, Munich, 1987, ISBN 3-406-31591-7

- Winfried Schich: Die Entstehung der mittelalterlichen Stadt Spandau, in: Wolfgang Ribbe (ed.): Slawenburg, Landesfestung, Industriezentrum. Untersuchungen zur Geschichte von Stadt und Bezirk Spandau, Colloqium-Verlag, Berlin, 1983, ISBN 3-7678-0593-6

- Oskar Schwebel: Die Markgrafen Johann I. und Otto III., in: Richard George (ed.): Hie gut Brandenburg alleweg! Geschichts- und Kulturbilder aus der Vergangenheit der Mark und aus Alt-Berlin bis zum Tode des Großen Kurfürsten, Verlag von W. Pauli’s Nachfolger, Berlin, 1900 Online.

- Harald Schwillus and Stefan Beier: Zisterzienser zwischen Ordensideal und Landesherren, Morus-Verlag, Berlin, 1998,