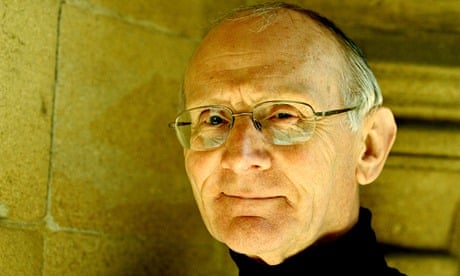

John Carey has been, among other things, a professor of English at Oxford, a prominent reviewer and book-prize judge, and an ardent bee-keeper. He tells us that he considered writing a history of English literature but decided instead to write "something more personal – a history of English literature and me, how we met, how we got on, what came of it". This, then, is his autobiography, but one in which books – books he read, books he wrote, books he admired, books he reviewed – play an unusually large part.

At times it feels like a series of free-standing disquisitions on individual books tied together with a fetching thread of reminiscence. He doesn't just mention them: he quotes long sections, he discusses aspects of their language or imagery, he explores why they move or appeal to him. It is for the most part very skilfully done. We follow him into what we think is going to be the secret garden of personal revelation, only to find we are given a brisk tutorial on Browning's dramatic monologues or the sound of Milton's verse. As with a lot of teaching, we attend through the less exciting bits because we're drawn to our teacher, curious to know what it all means for him.

The melding of the books and the life works particularly well when recalling the kinds of author who opened his mind when young – Chesterton, Shaw, Daudet, Horace (the whole book is a conscious tribute to a particular kind of 1950s grammar-school education, as these names suggest). But it starts to feel more contrived in later sections, above all when he remorselessly summarises the reviews he wrote of some 20 assorted books, mostly non-fiction. Perhaps this was meant to illustrate something of the randomness of the reviewer's life, or Carey's omnivorousness as a reader, but in practice it engenders much the same feeling as it does when someone gets you in a corner and starts telling you, at length, about books you haven't read or films you haven't seen.

The best bits, as so often in autobiographies, come when he writes with real affection – whether about playing as a child during the second world war, or about his happy marriage, or about gardening at his cottage in the Cotswolds that "seems deep in the country". Or about his bees. These hardworking creatures prompt him not just to admiration – "almost everything about bees is amazing" – but to some of his most winningly poetic touches, as when he recalls "the sight of bees on the landing board waddling up into the darkness of the hives, the orange pollen-packs on their back legs shining like brake lights". These are moments of pastoral when the groundedness of a more rural existence is invoked to show up the shallowness of literary London or the futility of academic politics; after all, he has found a better class of buzz.

Best of all, perhaps, are the few spare but generous passages about his father, a man who in the early 1930s fell from more than comfortable wealth to a somewhat straitened existence as an accountant, yet who remained upright and unembittered. Carey recalls taking his father shopping just a couple of days before he died of a stroke. His father asked to stop at a greengrocer's "where he bought a bag of peaches as a surprise for my mother. It was just an ordinary brown-paper bag with four or five peaches in it, but it was his last present to her, and I often think of it as a symbol of what he was – unshowy, kind and faithful." Carey's respect for his parents was increased by the fact that they had to care for his older brother, who developed a deteriorating form of mental disability, something he has not felt able to write about before.

I had hoped that this book might throw some light on the long-standing puzzle of why Carey, manifestly clever and cultivated (and, according to all reports, kind and likable in person as well) should from time to time lock himself into the persona of the chippy plain man bent on taking all those toffs and poseurs down a peg or two. There are a few clues, though, alas, there are also fresh instances of the pattern. A combination of the class-consciousness of 1950s Oxford and a veneration for Orwell may have something to answer for.And so, more speculatively, may a kind of unease about the agreeableness of his own life and the success of his own career. He went up to Oxford on a scholarship in 1954 and never left. He got a permanent teaching position there when he was 26, moved to a richer college four years later, was elected to the premier chair in English at the exceptionally early age of 40, became the Sunday Times's lead book reviewer three years later, and so on. Perhaps some of his hostility to "intellectuals" is a kind of perverse affirmation that, despite his glittering career, he really is on the side of "ordinary" people (he's pretty free with these two dubious categories).

Yet when Carey repeatedly insists that most academic literary scholarship is "calculated to repel any sensible ordinary reader" and that he therefore had resolved "never to write such stuff myself, and to deride it whenever I came across it", we begin to feel that there is some compulsive reflex at work here. Much academic writing is indeed poorly written; so is much non-academic writing, come to that. But structuring everything around a binary contrast in which "academic" equals pretentious and (deliberately?) unreadable while "ordinary" equals authentic and down-to-earth is silly and reductive, obstructing any deeper thinking about these issues. It also panders to a familiar anti-intellectualism that sneers at that very life of the mind of which Carey is, in other modes, such a fine exemplar. Similarly, he insists that it's "blindingly obvious" that "judgments of art and literature" are "matters of personal taste – what else could they be?" Well, quite a few things, actually, as writers on aesthetics have explored down the centuries. It is not that there is nothing to be said in favour of the view that Carey puts forward so belligerently; it's that his village atheist stance is intended to shut down discussion on the tendentious grounds that all other positions are attempts by self-appointed elites to disparage the taste of – yes, those "ordinary" people again. No doubt if we had to choose between Carey's robust scepticism and some braying fraud intent on patronising us we know who would get our vote. But why reduce such an interesting and complex question to that impoverished choice?

Again, when he is speaking of the marvellous Faber Book of Reportage he compiled in 1987, he can't resist pushing his point too far: "All knowledge of the past that isn't just supposition derives from people who can say 'I was there'." Well, first-hand reporting is indeed a valuable kind of source, though also sometimes problematic, but this wilfully disregards the complex way in which historical understanding is built up in favour of a blokeish insistence that if it's not eyewitness testimony then it's a load of hooey.

These reflex jabs connect to something deep in Carey's identity, as this autobiography makes clear, something to do with class and resentment and aggression. Among the clues are his reference to "the self-confidence I'd so envied in Shaw" when he was young and his acknowledging "how desperate I was to succeed" as an undergraduate; praising a later colleague's "magnificently abrasive" book is revealingly self-reflexive, too. He takes evident pleasure from the fact that the first colleague who walked out of his inaugural lecture, in protest at his sweeping condemnation of literary criticism, "was of royal blood, and, it was rumoured, 57th in line to the British throne". After all, what better vindication of the Carey line than that it riled both dons and nobs?

Even the happy memory of his and his wife's earliest discovery of the pleasures of holidays in Normandy is used to make a point: "On our first morning, the air was crisp and the sky eggshell blue. But while we were getting the map out of the Mini a sunburnt couple, clearly homeward bound from the Riviera, were huddling themselves into their Mercedes nearby and we heard the male remark, 'Beastly cold'." No doubt this is another of those eyewitness accounts, yet we are bound to notice the stylised contrast – the "ordinary" Careys thrilled by the freshness of the scene, the jaded wealthier couple returning from the haunts of the rich – even down to the stagey insistence on makes of car and "the male's" self-damning public-school idiom. But perhaps a lot of Carey's life has been like this – or, at least, experienced through these categories.

The most telling vignette comes when the 25-year-old Carey is doing some temporary teaching for Christ Church, then the most snobbish and socially exclusive of the Oxford colleges. The eminent economist and biographer of Keynes, Sir Roy Harrod, was a fellow of the college but always ignored the lowly Carey. "One night I was sitting opposite him at dinner when he had a guest, for whose benefit he was identifying the various notables seated round the table. I heard his guest ask who I was, and Harrod replied, quite audibly, 'Oh, that's nobody'." As we read this, we start to feel indignant on Carey's behalf and to despise this kind of calculated rudeness. But as we read on, we are constantly prompted to wonder about the distorting effect of psychic wounds of this kind on his later writing.

Carey himself reflects at one point that Harrod "and people of his ilk" would "have despised my father", as he himself had felt despised on that unpleasant occasion, and that this intuition lay at the root of his attack on Bloomsbury and other intellectuals in his much-cited, much-criticised 1992 book The Intellectuals and the Masses. Seeing that overstated polemic as, indirectly, a vindication of his father may give it a partial intelligibility, even a kind of nobility, that it otherwise lacks. Yet if that was the case, one can't help wondering why the hugely successful Carey should have been using his literary opportunities to settle such obscure scores more than 30 years later. The Unexpected Professor chronicles a rich life with humour and occasional vivid touches, but it also suggests that some wounds never heal.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion